Bassist / Composer François

Rabbath

A Conversation with Bruce Duffie

François Rabbath was born March 12, 1931

in Aleppo, Syria into a musical family. Having began the double bass at

the age of 13, Rabbath studied at the Paris Conservatoire and began his

career accompanying Jacque Brel, Charles Aznavour, and Michel Legrand among

others. In 1963 he made his first solo album on the Phillips label and met

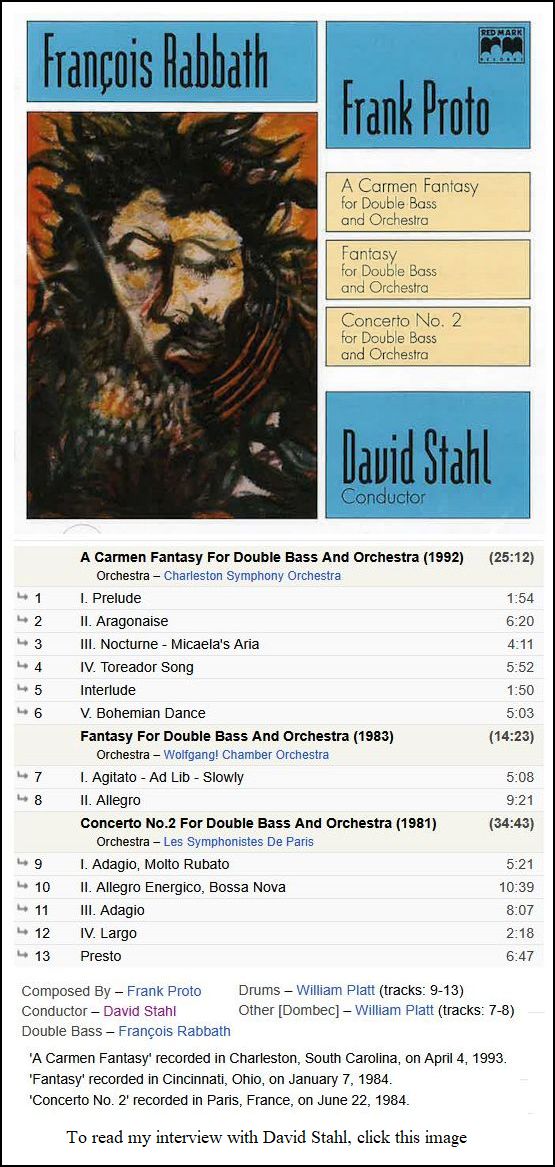

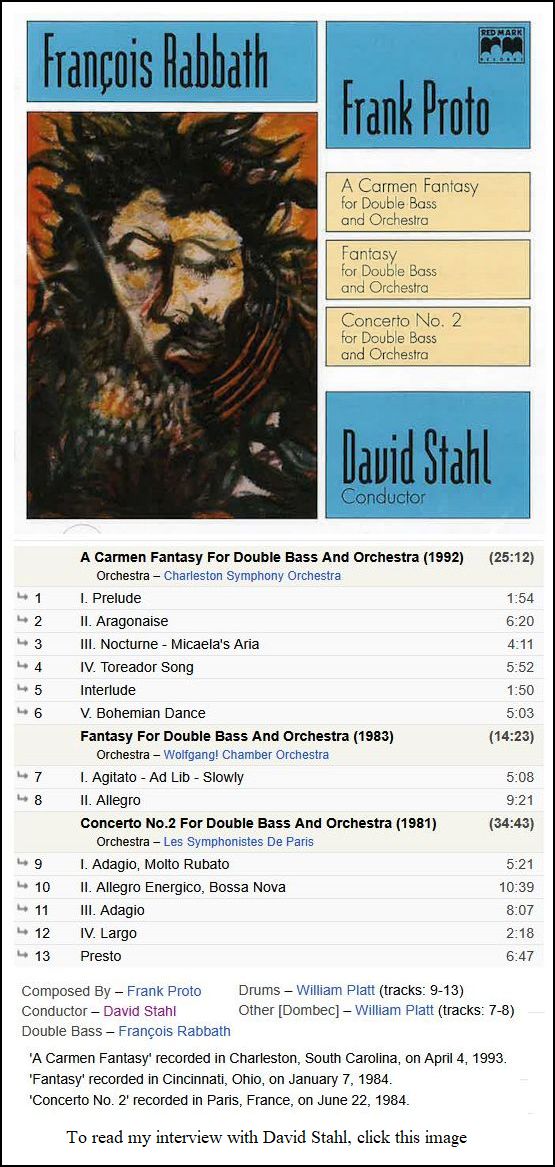

American composer-double bassist Frank Proto in 1978, with whom he developed a

close friendship and musical partnership. In 1980, the Cincinnati Symphony

Orchestra commissioned Proto to write the Concerto No.2 for Double Bass

and Orchestra, which Rabbath premiered in 1981. The pair would collaborate

on two further, similar projects. In 1983 Proto wrote Fantasy for Double

Bass and Orchestra for Rabbath at the request of the Houston Symphony

Orchestra, and in 1991 Proto penned the Carmen Fantasy for the two

to play as a duet with the composer at the piano. [Recordings of these

works are shown farther down on this webpage. See my interview with Frank Proto.

BD]

Rabbath forged a reputation as a versatile musician, equally comfortable

playing chamber music or improvised jazz. He was also an influential pedagogue.

His three-volume Nouvelle technique de la contrebasse outlined

how his method differed to that of Franz Simandl, in particular focusing

on his use of the left hand and detailed attention to the bow arm.

== Biography taken (mostly) from The Strad

website.

|

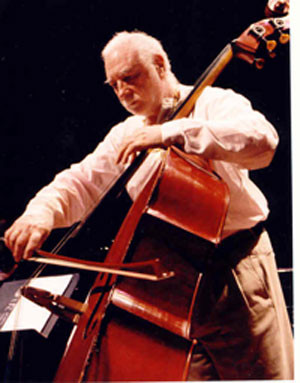

In mid-March of 1993, François Rabbath was in Chicago, and

graciously took time to have an interview. We met in one of the offices

very near the top of the 110-story Sears Tower [now the Willis Tower], which,

at that time (1973-98), was the tallest building in the world! Needless

to say, the view was impressive.

Rabbath was joyous throughout our session, and radiated a genuinely warm

and welcoming presence. His English was usually understandable, but

for this presentation I have straightened out his syntax, while leaving his

ideas completely intact.

La contrebasse is a feminine French noun, so Rabbath often

referred to the instrument as ‘she’, and I have left it that way in the

text . . . . .

Bruce Duffie: Has there ever been a time when

you would rather have a violin or a piccolo instead of the large double-bass?

François Rabbath: [Laughs] Oh,

I always hear that, always! Many people ask why I have that big

instrument, or why I don’t play a piccolo. But I imagine I would

never be here if I played the flute! [Both laugh] You don’t

imagine the bass. It’s an instrument that if you know to appreciate

it, it’s more than a wife. It’s more than a human being, because it’s

faithful to you. She never goes off with other people. She

always stays, and you will never be disappointed with her, never.

BD: Is she ever disappointed with you?

Rabbath: Yes, because sometimes she doesn’t

like the weather where I have to play outside. Many times I play

in a big stadium, like in Chile, or in Spain with 400,000 people, but it

was outside, and it was amplified. She doesn’t like the microphone

because she doesn’t speak as it should. So she’s mad with me, yes!

BD: You have to console her?

Rabbath: Yes. By playing her, she’s

very happy.

BD: Are you her master?

Rabbath: She was a virgin. When I had

her for the first time, they stole her from my home. It was for

me an enormous sadness that I had never had before. Alas it happened,

but I found this one. The man who had it hated her because he

failed all his auditions with it. When I asked him if he had one

I could buy, he said he had one. He had left her in the garage because

he hated her. He said I could have her. When I saw this bass,

with its wood and quality of the sound, I made a picture, and she answered.

It’s as if someone were in jail and wanted to get out. So I paid

him and took it home immediately. She was also a virgin to me. It’s

very important to know that you can make an instrument your own.

If you play in a good way to let it ring, and make the instrument sound,

it will be fabulous. But if you let her ring badly, you would destroy

her. The wood would not react normally, and you destroy the instrument.

It’s why he didn’t succeed in doing anything, because he didn’t

know how to play it. This was not just not knowing how to play her,

but with any bass because he was not a very good bass player. At

last, I had a chance to have it, and I am very, very happy that he was

not a good bass player, because now I have it. [Both laugh]

BD: She was probably happy that you finally

released her potential.

Rabbath: I think so, because now when you

hear her, the sound that she makes is marvelous. She becomes a

very big lady, a beautiful lady, and at last she’s become major.

BD: You play both classical concert music,

and also jazz and improvisational music. Do you play her differently

for those different types of music?

Rabbath: Sure. First, you have the normal

sound. If you know how to catch the normal sound

— where

to put the bow between the bridge and the fingerboard for each note,

the weight of the arms, and the speed of the bow

— you can have

just the pure sound for each. From there, you can manage to go a

little further up, and you can begin to obtain the rich palette of sound.

But just reaching the palette, you must also have the color. In

this case, if you have the color and the dynamics, and mix them together,

you go through the feeling of the people in your audience. In this

case, you can choose what kind of color to play, either classical or jazz.

BD: Do you ever mix those colors?

Rabbath: Sure! Always, because it’s the

future! I hate to be too straight. I like to explore, and

go anywhere in my exploration... but never ugly, or never against good

taste. I don’t want to hurt anybody. If you like the people,

you like to please the people, because you play for them to please them.

If they pay for a taxi, and they eat quickly to come to see you and take

their place, that means they like you. When they come to see you, you

must do everything in your power to give them everything that you have.

So, in a way, if you recharge all this sonority, and you mix everything,

you explode and use your power to say to them, “I

love you” in a certain way, then everything

will be all right. But if you come and ignore everybody, and say

you are a bass player, and I have come to play for myself, they can just

as well stay at home. However, I need the public to communicate.

BD: Do you play differently on the night of

performance than you do in your practice room?

Rabbath: In the practice room, it’s different

in a way, because in the practice room, I do it so as to work out at all

the technical problems. You cannot do that in public. Sometimes

at home I experiment and try out different interpretations. Every

day I play Bach, and every day it is different.

BD: Is Bach different, or are you different?

Rabbath: Oh, I think I am different every

day. Bach wrote notes. He’s a genius. He is the most

genius that has ever existed all down through the centuries. He

just wrote the music, but what music! I am so jealous. If

I could write just one piece like his, I would be happy. But if you

can feel this piece, and you can play it every day... [sighs] I

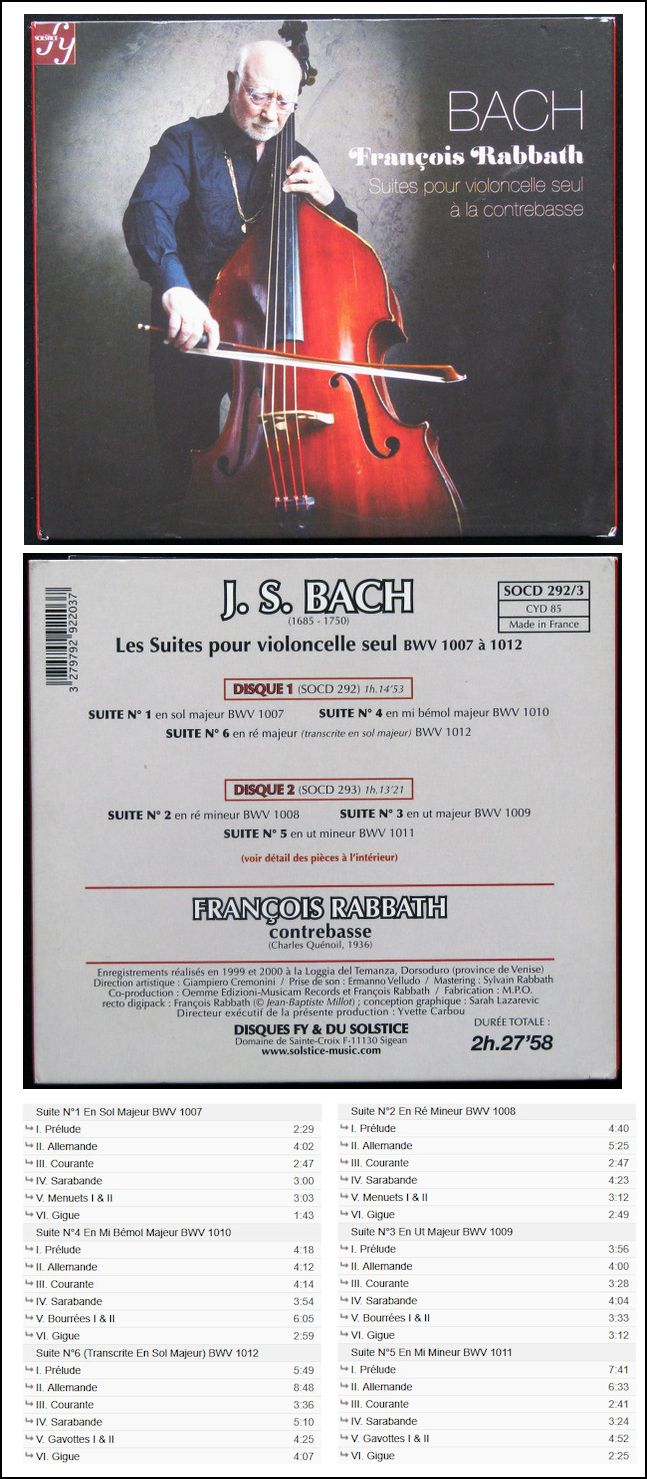

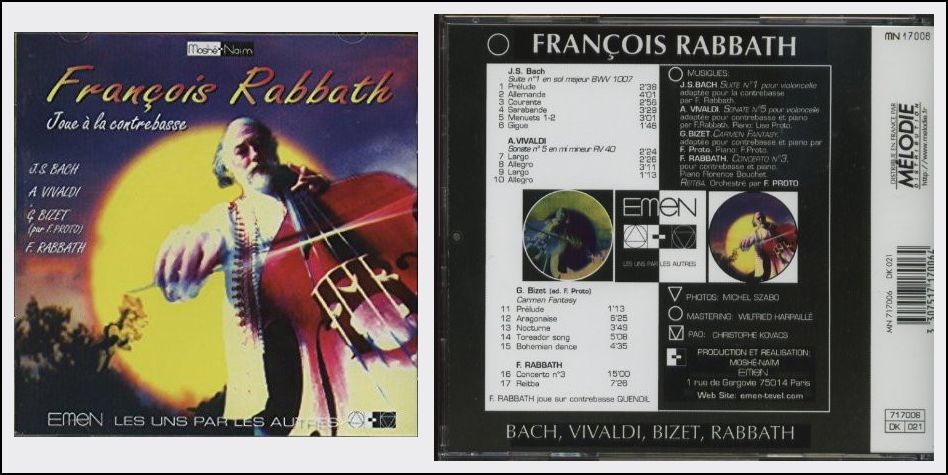

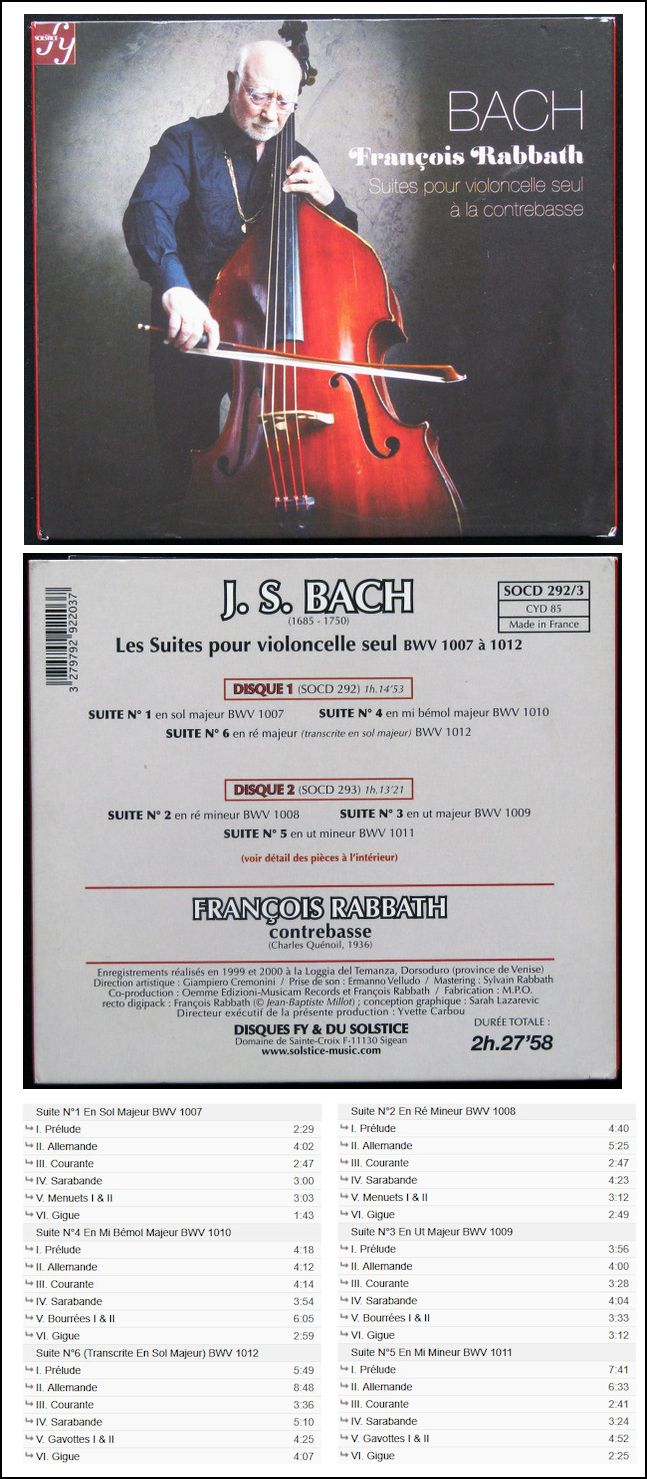

play the Suites of Bach for the past twenty years now.

BD: The Cello Suites?

Rabbath: Yes, and every day it’s as if I play

them for the first time. It’s not just because of me. It’s

because they are so rich, and each day you find different interpretations.

So it becomes new. [Recording of these works is shown above-right.]

BD: You play a lot of new music. Do you

find that the influence of Bach’s genius permeates some of the new music,

even your own new music?

Rabbath: Sure, for everybody. Every musician

in this world was inspired by Bach and others. I must have a pretext

or reason to compose music, some story, or some feeling, or some pictures.

I cannot compose just because I am inspired by something. I don’t

believe in that. But when I have some pretext or justification, I

compose, but I can say that my composition is more like an improvisation.

When I think about Bach, he was improvising his own music. [Sings

a few notes] He was making jazz music, and at this time he was a jazz

musician.

BD: Is this what you are trying to do, bring

back together the idea of improvisatory music along with the concert

music, having everything together for a total music?

Rabbath: Yes! You cannot give the public

something complete unless you have this free feeling for it. With

something written by someone else, you can feel it and translate it in

a way, but if you have some of your own improvisation in it, you become

the composer, and, in this way, you interpret the composition better. One

friend, Frank Proto, wrote the Carmen Fantasy for me [recording

shown below-left]. First, he sent me one part of the Toreador’s

Song, and he said to have a look at it. I said I don’t want to

play it because I know Bizet, and I know his opera. I had played

it so many times when I belonged to the bass section of the Paris Opera.

One day when Proto was in Paris, he said we should play it together.

I thought it could be a bit of fun, and he began to accompany what

I was playing. The chords that he played didn’t belong to Bizet! Bizet

just had simple chords, because in that century, you must not be very dissonant.

In this new way I discovered the genius of Bizet [sings a bit of the

Toreador’s Song], and it became fantastic. I told Proto to

write the rest, and he wrote a suite of five movements. It seems when

I must do something of my own, I feel it differently and totally. I

like to improvise. Bizet wrote the chords, so I just played it, and

in one part I began to improvise. Now I’m interested in Bizet, and

that’s it. You must improvise before the composer gives you the cadenza

to improvise on. Most instrument players never learn to compose or

improvise, so the composers give the performer a cadenza to show their technique.

Each one makes their own cadenza, but I refused that. I wrote

my own Concerto No, 3, and the improvisation is in the adagio.

[Recording of this work is shown at the bottom of this webpage.]

That means you must write an improvisation, which is the most important

passage in the concerto.

BD: Have you written down your improvisation?

Rabbath: Yes. You must write a melody

immediately and instinctively. When you use scales and arpeggios

to make a cadenza, it’s nothing because you just let your fingers go.

But when you have to build a melody, it’s as if you are writing the

melody in public, and that’s inspiring to explore in front of the public.

BD: Each time you play this particular cadenza

and improvisation, it’s going to be a little different, but it’ll be based

on the same ideas?

Rabbath: Yes. Fortunately for me, when

I play it for the first time, each time when I play, it’s almost exactly

the same.

BD: [With a gentle nudge] Almost???

Rabbath: [Laughs] Yes, almost, because

sometimes it depends. If the public loves me even more, I feel it.

It’s like electricity, and I will go on more. If not, I have

already written something, and I just share that with the public.

BD: Can there ever be a time that it gets

to be too much?

Rabbath: No, never, never. If you live

the moment, the public lives with you. It’s never enough.

BD: If another bass player were to take this concerto

that you’ve written, and work with the improvisatory sections, should they

take your ideas and base their ideas on yours, or should they have a completely

different improvisatory part?

Rabbath: It should be completely different.

If they have their own ideas, I prefer that. I give them the harmony

and let it go on.

BD: Would you be completely aghast if someone

were to take and notate your improvisation, and learn that exactly?

Rabbath: No, but it would be as if I wrote

the melody. He would not explode. He would not share in

public as if it were himself writing the music.

BD: Is this part of the problem of performers

today, that they’re not ‘exploding’ enough in public, as you say?

Rabbath: Yes. They don’t share enough. They

are on the stage, and the public is sitting in the hall, and there is

a separation.

BD: There’s a wall between?

Rabbath: Yes. Both he and the public are

there, and that’s it. The performers don’t speak to the public.

I cannot begin any recital without saying hello, without saying bonjour,

or without having any contact with them. Then, when they applaud

you...

BD: ...you’re acknowledging the applause.

Rabbath: Yes, but they haven’t made contact

with you. You must say hello. I then explain what the music

is about, and I can play. If you do that immediately, it seems they’ve

known you forever, and they share something special with you.

BD: [Gently protesting] But isn’t the

music supposed to be the contact that you have with the audience?

Rabbath: [Hesitates] Yes, but sometimes

it’s cold. Sometimes you must break the ice, if only to just say,

“Be my friend! I come here to share with

you an evening. I am not just coming to show how I play. I

would like to share with you what I feel.”

That’s different. I don’t think that the traditional classical

way is the best way.

BD: [Surprised] You don’t think so?

Rabbath: No! Many think it’s fantastic,

and I don’t contest the music, but others come and just play. They

do their job, and thank the audience, and go home! Perfect, perfect...

but it’s not me.

BD: Then let me ask the big question. What’s

the purpose of music?

Rabbath: To share something with someone.

To share a love with someone.

BD: To share yourself?

Rabbath: Yes, yes! You cannot share something,

or you cannot be the audience, and the audience cannot be you if you

have this glass wall between you. You can play very well, and many

people do play perfectly, but when I go, I forget. It was perfect,

but I don’t share anything with him, and he doesn’t share anything with

me.

* * *

* *

BD: You’ve expanded the technique of playing the

double bass because of things you have discovered on your own?

Rabbath: Oh, yes.

BD: Tell me a little bit about that!

Rabbath: I was born in a town that didn’t know

what a double bass was. When my brother was in an orchestra, he

brought with him the bass, and I discovered it for the first time. But

we didn’t have any professors to teach me, and I just found a Method

by chance in a tailor’s shop. I stole it because if I asked, he could

say no. So I stole it. I found this was a French Method

by Édouard Nanny (1872-1942), and I found many wrong things. I

was playing and I felt that if I did it this other way, it’s easier.

Finally, I discovered that I did everything wrong.

BD: Wrong according to tradition?

Rabbath: Yes. I found that I was playing

more easily, and felt I must speak with them and say there is an easier

way to play than this! So, I am self-taught, and I willed myself

into a totally a new technique.

BD: You explored every angle, every inch of

the bass?

Rabbath: Oh, yes! For each scale, I

have written 130 different fingerings. In this case, you don’t have

any way to do it wrong. You have many ways to work on it, and to

make it on a fingerboard where you know where to go without any problems.

But all the conceptions of the psychology are different. Difficulties

don’t exist anymore.

BD: Nothing is difficult???

Rabbath: No. At any age you can be a

virtuoso.

BD: You say nothing is difficult to play.

Could there be music written that is too difficult to accomplish?

Rabbath: Never. You can do everything, but

you need time. When I have a pupil who says something is difficult,

I say, “No! Stop using this word! Forget about this word!

You didn’t even know what the double bass was, and now you play. What’s

happened? It was difficult before, and now what you are doing is

not difficult anymore! So, the things that you think are difficult,

in the future you will do them!” Psychologically it’s totally different.

With the approach of psychology and awareness, everything has become a

different approach.

BD: Would these ideas then work for the violin

or trombone?

Rabbath: Sure, for everybody! Why not?

BD: Would they work for computer science?

Rabbath: Everything! We dreamt about

going to the moon a hundred years ago...

BD: ...and now we’re there!

Rabbath: Things have their own time. Take

the time and you will succeed, but you must know the secret as to how

to do it. You must know how to go in any particular space in time.

BD: Is there a single secret to playing the

double bass?

Rabbath: No, you must know the way and how to do

it. If you just keep the traditional technique in this century,

they knew how but there was only the one way. God gave me a chance

to discover by doing it myself a hundred different ways, and I didn’t just

choose one. I adopted all of them. It took me some time, but

in this case I discovered many ways to go everywhere. I have no problems

anymore!

BD: Have you have written all of these in

technique books?

Rabbath: Yes.

BD: Do you foresee a time, a hundred or two

hundred years from now, when someone will wonder how you could do it

in such a terrible way, and show a much better way?

Rabbath: I would agree with him, sure!

BD: They’d throw you out like you threw out

Nanny???

Rabbath: No, I don’t throw out Nanny!

Nanny is one way. I began to play Nanny’s way. How could I

throw it out? It’s the basis, but I would like to see one day will come

and build more.

BD: Someone will build on top of you?

Rabbath: Sure!

BD: The person who builds on top of you then

will have to learn the Nanny technique?

Rabbath: Nanny, and Franz Simandl (1840-1912),

and my Method, and other things.

BD: At what point does it become too much

to learn?

Rabbath: If you know how to go, you go very quickly.

The only thing is to know how to do it. It is possible that you

can learn for a hundred years and just know a little, and you can learn

for two years and learn so much. It all depends on the way to learn.

If you do one movement not correct, you will do it all your life incorrectly.

But if you know how to do it correctly, you just do it one time

and you know about it. That’s the secret, to know how to do everything

correctly to grow up and to make progress. If you do one thing

badly, you build everything in this bad way and it cannot support you.

If one thing falls down, everything else falls down.

BD: So, you have to have the basics correct?

Rabbath: Everything must be correct... not just the

basics, but everything.

BD: Is this the advice you have for other people

who play double bass, or indeed play any instrument?

Rabbath: Yes, sure, sure.

BD: What advice do you have for composers

who want to write solos or concertos for the double bass?

Rabbath: What I say is do what you like. We

have the opportunity now with the new technique to do what everyone can

dream. So the composer can do what he likes to do, and can be free

to write what he likes. It’s our problem to resolve any problems.

BD: The composer doesn’t solve the problems?

Rabbath: No. The composer makes the problems

because he writes what he’d like to hear. If they begin to think that

this is possible or this is not possible, then he would limit his composition.

BD: But when you are both composer and performer,

are you both the problem poser and solver?

Rabbath: When I am the composer, I don’t think

about my own performing problems.

BD: [Surprised] You can separate them???

Rabbath: Yes. When I compose, I write without

the double bass. I like to do something in my mind [snaps his fingers]

very quick. Then when I pick up the bass, I wonder what am I doing?

Why did I write that? I am foolish!

BD: But then you solve it?

Rabbath: Yes. Playing solves the problem, and

this is how I also discover the way to use the adrenaline. When you

are afraid to solve the technical problem, the adrenaline gives you a very,

very beautiful and very strong energy. It saves your life when you

are in danger. I wrote something very, very fast, and the next

day I had to apply this in a concert in Paris. Five thousand people

were coming, and I had to play this piece. I never succeed in going

so quickly in this passage. The day before, I was playing it before

I went to sleep. I didn’t have any problem when I dreamt about

it, so I knew that’s the way! The next day I did exactly the hand

motion that I did when I had my eyes closed.

BD: And it worked?

Rabbath: Yes, because the mind was locked.

In my mind I said it was difficult, but it’s not difficult!

BD: All the finger technique comes from the

mind?

Rabbath: Sure, but you move because your mind

says you must move.

BD: Does the emotion come from the mind, or

does the emotion come from the heart?

Rabbath: [Smiles] Ah, the heart. That’s

different. I’m not a doctor, but I know that the emotion is more

from my heart.

BD: Then how do you combine the heart and

the mind in one piece of music?

Rabbath: I let it go, and they arrange themselves.

I don’t want to manage all that. I know that I love the public,

and this love shares everything with them. But when I have to

resolve a technical problem, I do it in a way that there is no more music,

no more emotion. The emphasis is just put on the technical problem.

We are physical, so we must train our muscles. I found out in training

my muscles that I must also train my endurance, and then my endurance

gives the technique. It is not something quick that gives the technique.

I must do two hours of scales without stopping. I have the time to

do that, but without stopping one minute, because I need endurance.

BD: You found out that you needed it instinctively?

Rabbath: No. When I made my first

record, there was a cocktail party, and the Ambassador of Japan was coming,

along with many other people. He heard me play, and after a while

we were alone. He took my hand and squeezed it in order to say

thank you. He was small, but his grip was like a machine. I

asked him how he could do that, and he said, “Endurance!”

This got into my mind, and I thought about how to train my muscles

for the music.

BD: You put the two ideas together?

Rabbath: Yes! When I was young, about sixteen

years old, I was playing many things. After a while, I knew that

if I wanted to be a virtuoso, I must play like a virtuoso, and I must work

like a virtuoso. I imagined it, but I didn’t know about two-hour

scales, etc. To train my muscles, it’s different. It’s a gift,

as I discovered in an instant [clicks his fingers]. Because I see

all this, I am very interested in the people. I love the people and

I watch what happens. It’s why I discovered all that. If I didn’t

care about that, I wouldn’t even think about it. But it’s a gift from

God to discover that.

BD: Were you born a virtuoso or did you make

yourself into a virtuoso?

Rabbath: Nobody is born a virtuoso, but everybody

can be a virtuoso!

BD: [Genuinely surprised] Really???

Rabbath: At any age! I have the proof!

Even people who are forty-two years old can become virtuosos, because

if you don’t want to be a self-centered person, and you want to share

something with the people, you can trust yourself and do it. But

if you want, you can be an egotist like Paganini. It took one hundred

years to play his tunes very well because he didn’t tell anyone the way

to play them. I wrote the books to show the way to be a virtuoso.

BD: Would that have lessened the impact of Paganini

if we had had video tapes of him playing?

Rabbath: Oh yes, sure. We would have

done it more easily before. We had to wait until the twentieth century

to do it.

BD: Would that have been a good thing to have

had it so quickly?

Rabbath: Sure, because the violin would have been

more advanced by now. It’s not normal that the bass waited a century

before anybody wrote a Method, so I had to do it myself now.

It is not normal, because the institutions come down heavily in that they

refuse to recognize you. They refuse to see it’s a possibility. I

know it’s possible, but you have work on it.

BD: Does it please you, or give you a

sense of happiness and satisfaction to know that you have helped to

bring the double bass into the forefront?

Rabbath: If you love the double bass, yes, but for

the love of the double bass, not for the power. I know there are

many... When I die, I don’t want to die alone. That’s me.

When my mother died, she was so loved by everyone. There were about

twenty-five in the room around her when she died. I was looking at

her, and I knew it was fantastic to be helped like this. If I die

tomorrow, I am sure that many bass players will be with me.

BD: And many bass lovers too!

Rabbath: Sure, sure! That is very important.

Here’s a fantastic story, the most beautiful story that has happened

to me. Before I came to Chicago to play the Carmen Fantasy for

the first time, I tried it in Toulouse to see how the orchestration would

go. We played it for a small gathering, and we recorded it to send

to Proto to arrange it for when I came here. That way, in Chicago

it would be perfect. When I finished playing it, a ninety-one-year-old

man, and a seventy-two man came up to me. The ninety-one-year-old

had a briefcase. He opened it and he took my Method.

He asked if I would sign it, and I asked who he was. Well, he was

the principal bass player of the Toulouse Symphony! He said, “I

have trouble with my eyes. I’m going to have an operation on my

cataracts, so that I will read your Method even better.”

When you have this lesson of someone fantastic like this, you become

humble, and you don’t want to waste any time. The other man, the

seventy-two year old, was the principal of the Chamber Orchestra of Toulouse.

They worked together on the Method to make progress. Fantastic,

eh?

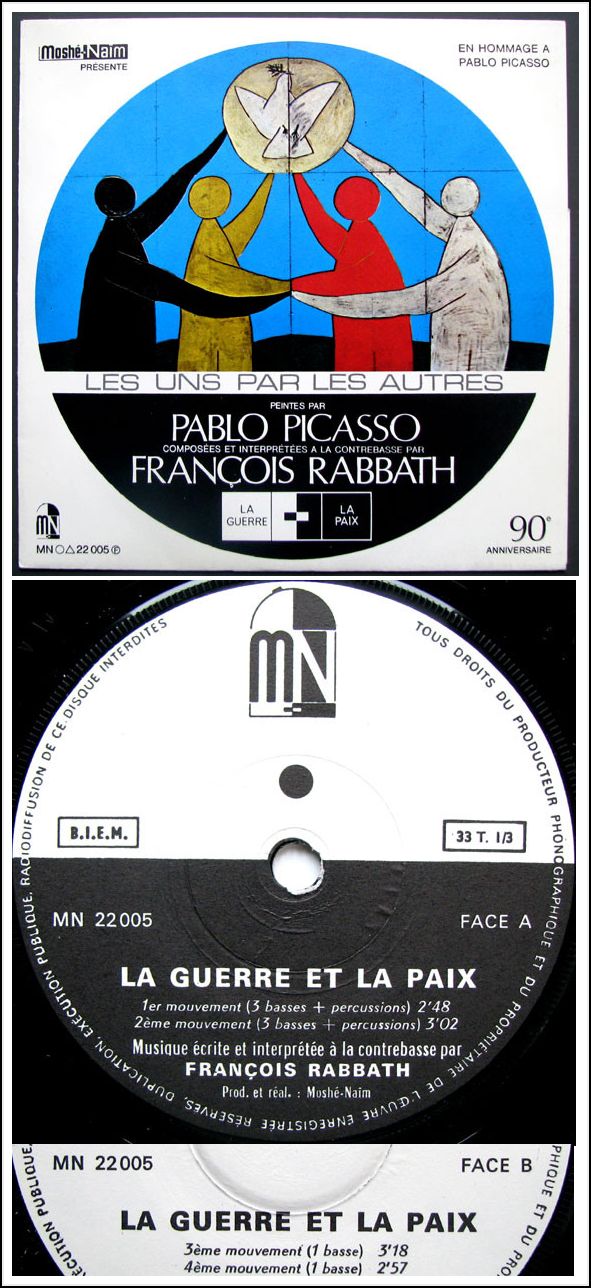

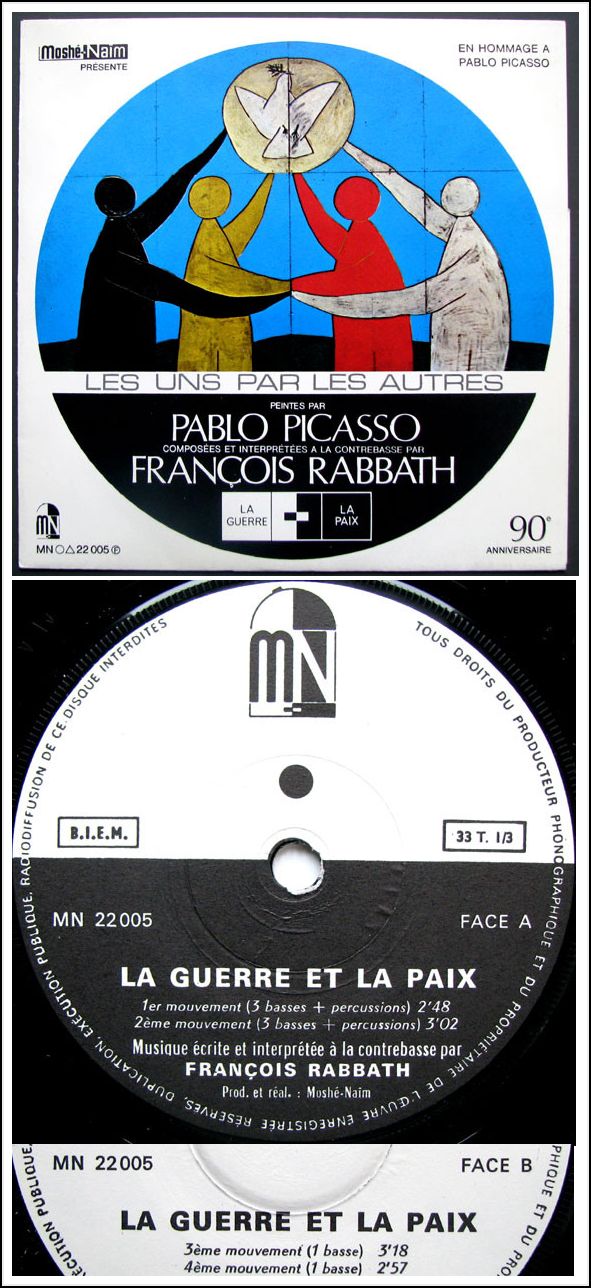

BD: Absolutely! [Note that the recording

shown at left is a seven-inch 33 rpm disc, and features Rabbath as both composer

and performer.]

Rabbath: When you see that, you know that we must

live for the instrument. Not to fight, or say this is the biggest

and this is the smallest. No. I can say something that everybody

must know. Each bass or each instrument player is unique. Nobody

can imitate another because everybody must play and go his own way with

his own feeling. I can resolve their technical problems if they have

some, but I cannot resolve their own personality. They can never ever

be me, and I never ever can be them. We are unique.

BD: So their music is their personality?

Rabbath: Aha! I never tell anybody what

is the way to play this piece, even my own pieces! When I hear

them played by another instrumentalist, and he asks how I do it, I say,

“Like you do!” Bach has

lived until now because each one does it in his own way. How many

times do you play a record? After a while you stop playing it.

If everyone were to play exactly the same way, you could just hear the

record once and that would be it! If you want this music to live,

you must have a difference. Otherwise you cannot be unique.

BD: You want the music to live in everyone?

Rabbath: Sure, and everyone can have different

ways to say, “I love you.”

I love that.

* * *

* *

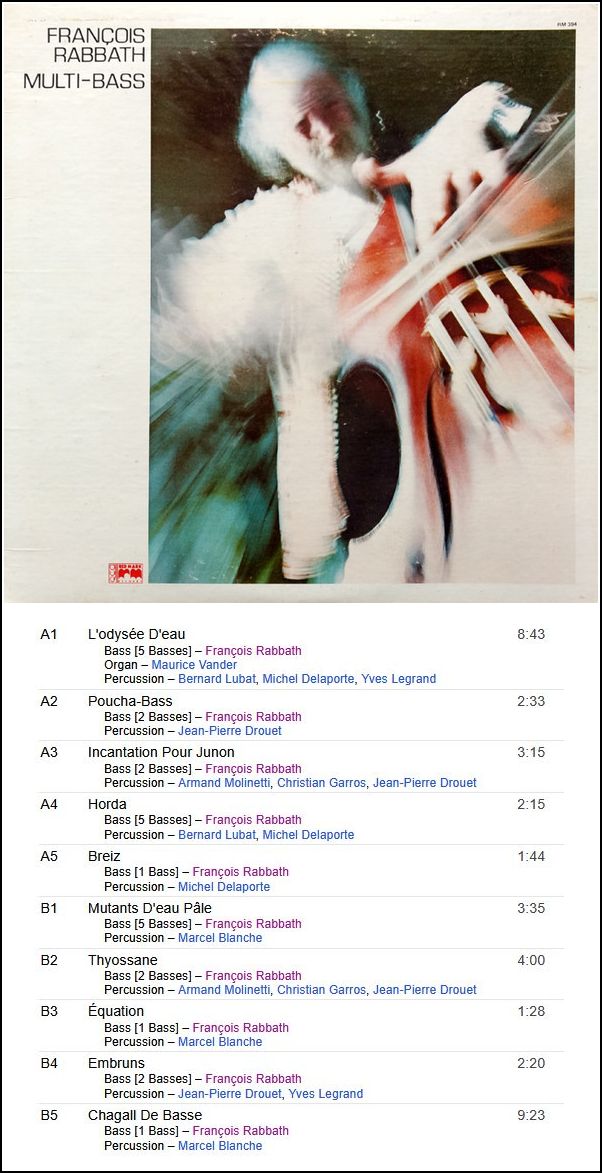

BD: You mentioned the recordings. Are you pleased

with the recordings that have been made of your performances?

Rabbath: Sometimes yes, but I’ve never heard them!

I prefer that other people hear them.

BD: [Mildly shocked] You make the record

and that’s it??? You just let it go???

Rabbath: I think so. You must be more

relaxed. I made a record when I was young and very energetic. Then,

after having gained experience, I played the same things maybe differently,

and I accept that. Someone from my company said, “We

must do it again, and take the older one off the market.”

I said, “No, it was like a book.”

If you are young and you are old, to do exactly the same is impossible.

BD: But both are right?

Rabbath: Sure! In its time and it’s own way,

even if you play better, each one was made in its own case. When

you go to an art exhibit and see works by Picasso or Dali, you can see

the evolution of their work. It’s fantastic. Can you imagine

if everything were the same?

BD: [Gently protesting] But each painting

always is the same. Each piece of music is never the same.

Rabbath: Yes, but when you put it on a record,

it’s always the same. So if you have different interpretations,

it will be better.

BD: Always better?

Rabbath: Better in the interpretation.

It’s not better in all ways, but different.

BD: [At this point we stopped for a moment, and my guest

recorded at Station Break.]

Rabbath: Hello, this is François Rabbath,

and you’re listening to Classical 97, WNIB in Chicago. [This

is what I asked of all my guests, and he instinctively added, “I

love you!”.]

BD: Thank you for coming to Chicago, and thank

you for being a double bass player!

Rabbath: [Laughs] If we love the music,

that’s the most important. The rest is nothing.

© 1993 Bruce Duffie

This conversation was recorded in Chicago on March 18, 1993.

Portions were broadcast on WNIB three years later, and on WNUR in 2002, 2005,

and 2018. This transcription

was made in 2025, and posted

on this website at that time.

My thanks to British

soprano Una Barry for

her help in preparing this website

presentation.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed

and posted

on this website, click here.

To read my thoughts

on editing these interviews for print,

as well as a few other interesting observations,

click

here.

* * * *

*

Award -

winning broadcaster

Bruce Duffie was with

WNIB,

Classical 97

in Chicago from 1975

until its final moment

as a classical station in February

of 2001. His interviews have

also appeared in various magazines

and journals since 1980, and he continued

his broadcast series on WNUR-FM,

as well as on Contemporary

Classical Internet Radio.

You are

invited to visit his website for

more information

about his work, including selected

transcripts of other interviews,

plus a full

list of his guests.

He would also like to call your attention

to the photos and information about

his grandfather,

who was a pioneer

in the automotive field more than a century

ago.

You may also send him E-Mail with

comments,

questions and suggestions.