|

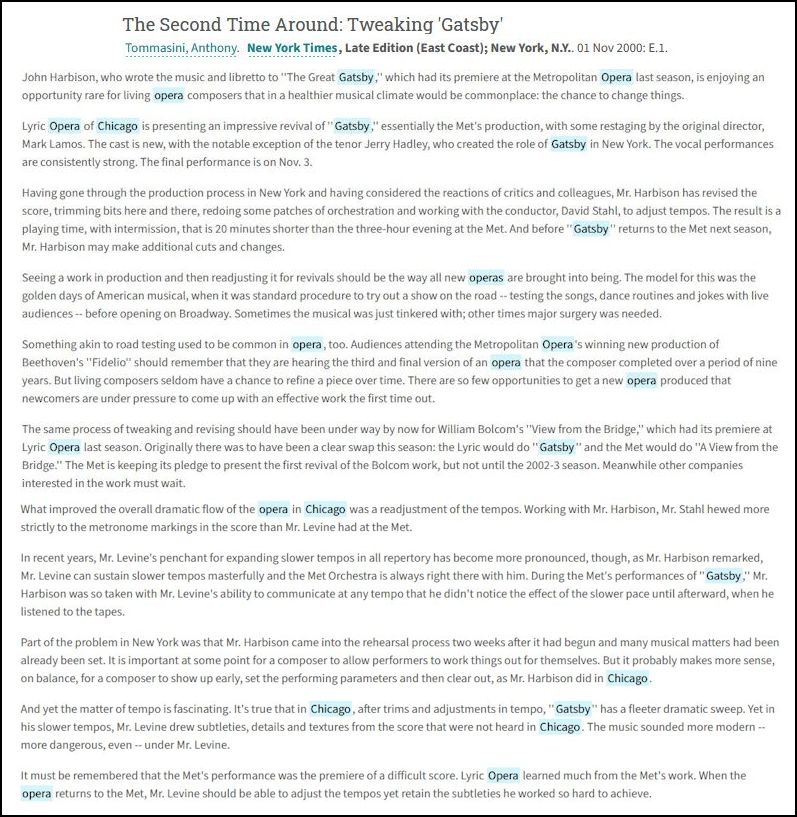

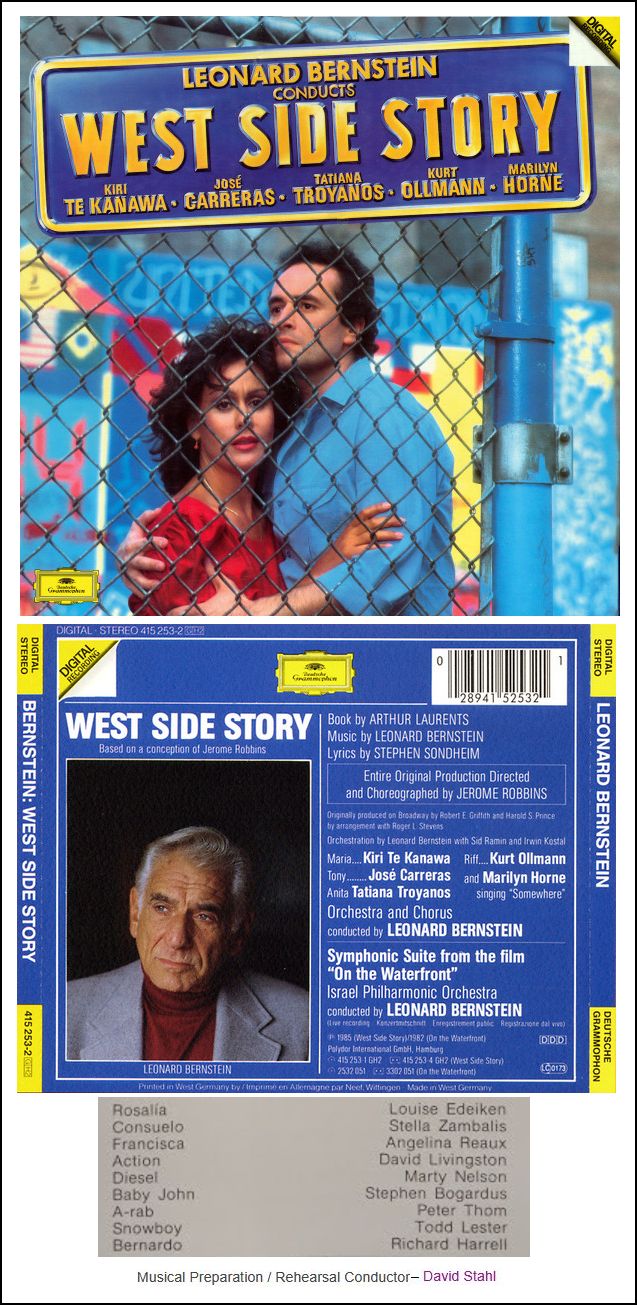

David Stahl (November 4, 1949 – October 24, 2010) was an American conductor who served as the music director and Intendant of the Staatstheater am Gärtnerplatz in Munich, and the Music Director of the Charleston Symphony Orchestra. A student of Leonard Bernstein, he was famous for his interpretation of Mahler's works. Stahl was born in New York City, the son of Jewish émigré parents. David's father, Frank L. Stahl, was an engineer who took part in the restoration of the Golden Gate Bridge in the 1980s. He was born in Fürth, Germany and attended the same elementary school as Henry Kissinger. Edith Stahl, David's mother, immigrated to New York in 1938 from Essen, Germany. David's grandfather, Dr. Leo Stahl (m. Anna Regensburger), was the Jewish Community Leader of Fürth during the Nazi era. Leo was interned in Dachau concentration camp from November 11 to December 7, 1938, and emigrated to England in 1939. Arriving in New York in 1947, he was, according to Das Schicksal der jüdischen Rechtsanwälte in Bayern nach 1933, by Reinhard Weber, unsuccessful in business and died there in 1952, aged 67. Frank's sister Liselotte, after a time in Manchester, England, also came to New York, where she died in 2007. David studied conducting at Queens College, City University of New

York. After

making his Carnegie Hall debut at age 23, he came under the tutelage

of Leonard Bernstein, eventually taking over as music director of the Broadway

production of West Side Story. [The recording conducted by the composer,

in which Stahl assisted, is shown below.] In 1984, he became Music Director

of the Charleston Symphony Orchestra; a position he remained in until his

death 26 years later. In 1996

he was invited to be guest conductor at the Staatstheater am Gärtnerplatz.

He assumed the title of Music Director there from 1999. He also worked

frequently as a guest conductor of operas and musicals at major theaters

around the world, including the Bavarian State Opera, the Deutsche

Oper Berlin, the Lyric Opera of Chicago, and the New York City Opera

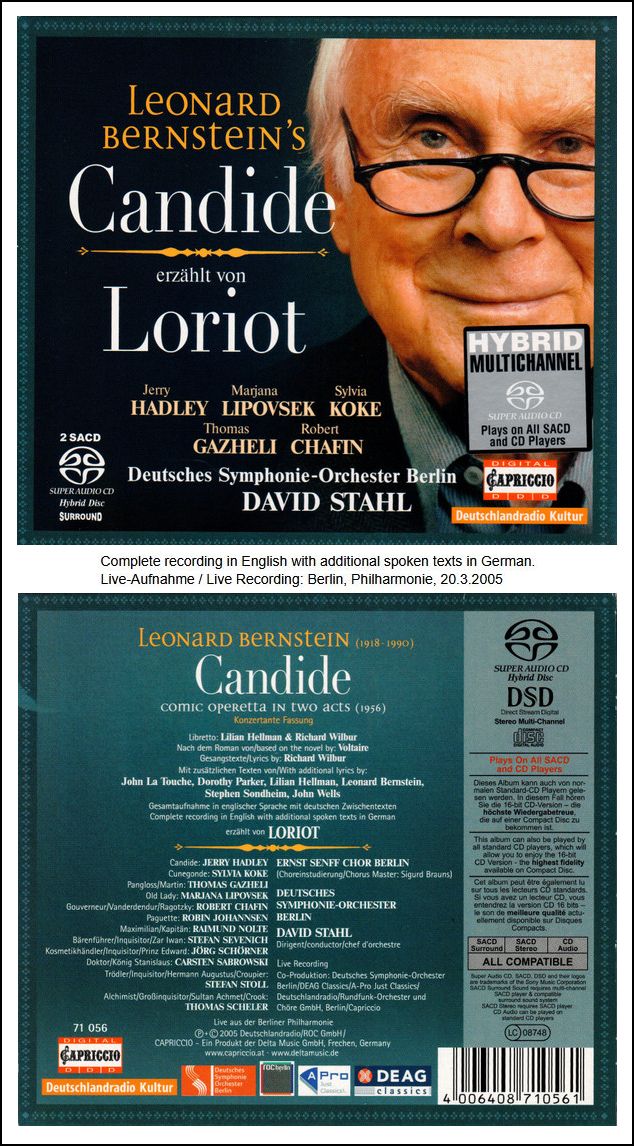

among others. As an enthusiast of Bernstein, he had been behind several revivals of Candide, including conducting an acclaimed 2003 production, which was sung in the original English, with German narration spoken by Loriot. [A recording of this is shown below.] Stahl also led a 2008 production in Charleston, South Carolina. He was also involved in the staging of a notable production of Gershwin's Porgy and Bess in Charleston, the city where the opera is set, which went on to tour internationally in the early 1990s. In 2009 he celebrated 25 years at CSO and 10 years at the Gärtnerplatz. David Stahl died of lymphoma on October 24, 2010. His wife, Karen, had died during the

previous month. The couple had two children, Anna and Byron. David had

met Karen when his daughter from his first marriage, Sonya, became a student

in Karen's kindergarten class at Ashley River Creative Arts Elementary. == An appreciation of David Stahl, by composer

and double bassist Frank

Proto, is at the bottom of this webpage |

|

I met David in 1976 while a member of the Cincinnati Symphony Orchestra. He joined the orchestra after having won the Exxon/Arts Endowment Conductors Program award. Discovering that we were both expatriate New Yorkers, a lifelong friendship began. David's official position with the CSO was conducting assistant. This meant that unless there was a calamity of cataclysmic proportions, he would likely serve out his three-year stint never actually having the opportunity to conduct the orchestra. Conducting assistants generally attend rehearsals sitting score-in-hand, trying to stay alert in case the music director turns around and shouts something like "was the second horn OK in measure 465?" They also serve as general gofers at concerts and recording sessions, and being at the bottom of the orchestra's totem pole, suffer the wrath of management personnel, librarians, stage hands and musicians whenever a scapegoat is required in a face-saving situation. The period between 1976 and 1980 was a tumultuous one for the Cincinnati Symphony. Music director Thomas Shippers, an important mentor in David's life, fell ill. He missed most of the 1976 season and passed away in 1977. The orchestra management was constantly scrambling for last-minute guest conductors and the lowly conducting assistant was the last thing that occupied anyone's mind. David was searching for ways to hone his skills. Opportunity knocked in an unusual way one day. The orchestra was preparing a fund-raiser in which musicians would offer their services, musical or otherwise, to patrons who agreed to donate a set amount of money. With our brilliant young principal cellist, Peter Wiley, we cooked up a plan where I would write a cello concerto which Peter would play and David would conduct if someone would donate $2000.00 to the orchestra. We then convinced Walter Susskind, who was serving as the orchestra's Music Advisor until a new Music Director could be found, to approve the plan, promising to schedule the work on a future subscription concert. Since most musicians' premiums were listed at around $50.00 to $100.00 we weren't given much chance to sell ours. As it turned out, an interested contemporary music aficionado, in the person of Marion Rawson, bought our premium and the new concerto was played during the 1978-79 season. For most of the Cincinnati audience this was the first opportunity they had to see David conduct. They responded with a huge ovation at the end of his concert which ended with a roaring Symphonie Fantastique. The following year we submitted another premium for the fund-raiser. This time David would conduct a new double bass concerto that I would write for François Rabbath. We ran into a bit of trouble at first: "Bass concerto! you guys are crazy. No one will ever buy that one!" Tripling our price didn't seem to be a wise move either. But, wonder of wonders, Marion Rawson again came forward. Still, some P.R. department doubts and worries about attendance at a concert with an unknown bass player and a young conductor existed. But a determined David was out doing interviews all over the place. His official stint with the orchestra was over and he was now appearing as a guest conductor. His concert drew the 2nd largest audience of the 1981-82 season. Later in 1982 I wrote the Fantasy for Double Bass and Orchestra, again for Rabbath. After the premiere with the Houston Symphony, I wanted to record the piece. David took the score, learned it in less than a month & conducted the sessions like a seasoned pro. He was barely 30 years old. A couple of years after that he took over the reins in Charleston, and slowly built a first-class sounding ensemble. During my years in Cincinnati we raided David's orchestra several times, getting principal clarinetist Richard Hawley, and concertmasters Alexander Kerr and Timothy Lees to fill the same positions in our CSO. Fate with the bass continued to strike, when in 1993 Rabbath and I went to Charleston to perform and record my Carmen Fantasy for Double Bass and Orchestra. Despite having a full week of concerts, including a couple of huge symphonies, David delivered a beautiful performance and recording of the work, filling out our new CD: Works for Double Bass and Orchestra. His orchestra continued to move in an upward arc both musically and technically. Working in the confines of a small orchestra and operating on a shoestring budget, is challenging for the best musicians, but we can see how it was preparing him for his eventual appointment as music director of the Staatstheater am Gärtnerplatz in Munich. I wish I had a recording of David's phone call making the announcement. He was at the top of the world! A few years later we collaborated still again. This time on a violin concerto for former Charleston (Cincinnati and Royal Concertgebouw) concertmaster Alexander Kerr. David, who was passionate about the Holocaust, wanted a big violin concerto, to be performed on the 60th anniversary of Kristallnacht. He encouraged me to educate myself on the subject before writing a note. I took his advice and will be eternally grateful for it. A thoroughly mature David Stahl brought Can This Be Man? to life in 1998. The tears that the performance by David and Alex brought to the audience that night quickly revisited me when I learned of his passing on October 24, 2010. So David, a last Ciao and a big thank you for bringing good things to so many lives while you were with us. Frank Proto |

© 2000 Bruce Duffie

This conversation was recorded in Chicago on October 6, 2000. Portions were broadcast on WNIB five days later. This transcription was made in 2025, and posted on this website at that time. My thanks to British soprano Una Barry for her help in preparing this website presentation.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website, click here. To read my thoughts on editing these interviews for print, as well as a few other interesting observations, click here.

Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he continued his broadcast series on WNUR-FM, as well as on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio.

You are invited to visit his website for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.