| Born in Louisville, Kentucky,

Paul Ramsier showed promise as a pianist at the age of five and began

composing at nine. At sixteen, he entered the University of Louisville

School of Music. His graduate studies included piano with Beveridge

Webster at the Juilliard School and composition with Ernst von Dohnanyi

at Florida State University. In his early career in New York City, he

was a staff pianist with the New York City Ballet where he was

influenced by Balanchine and Stravinsky. During that period he studied

composition with Alexei

Haieff. [Names which are

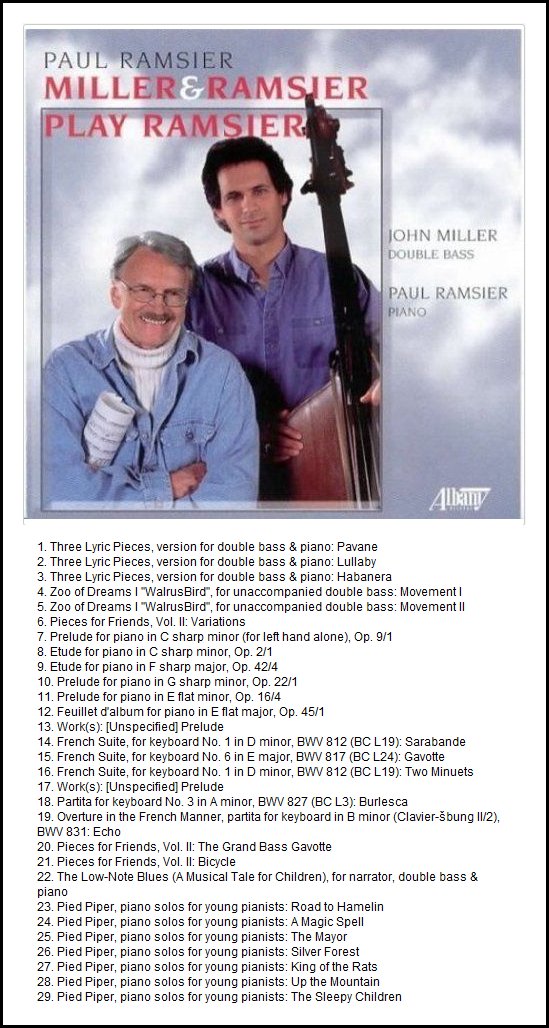

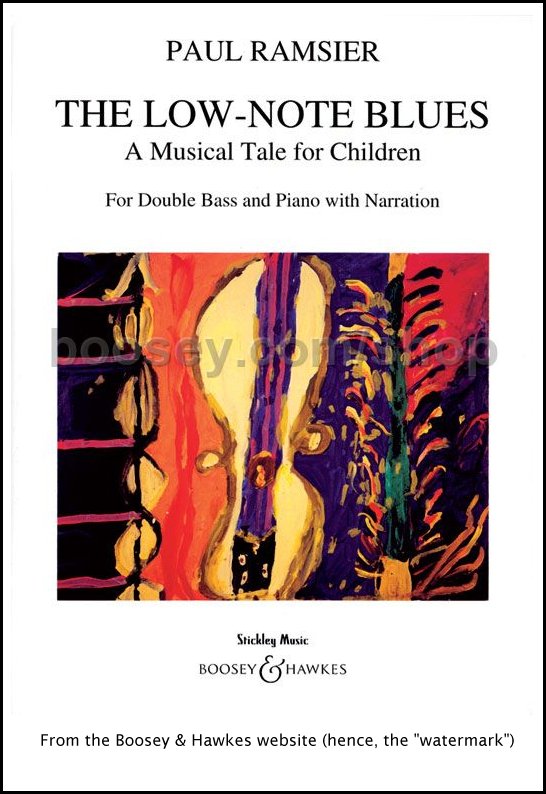

links on this page refer to my Interviews elsewhere on my

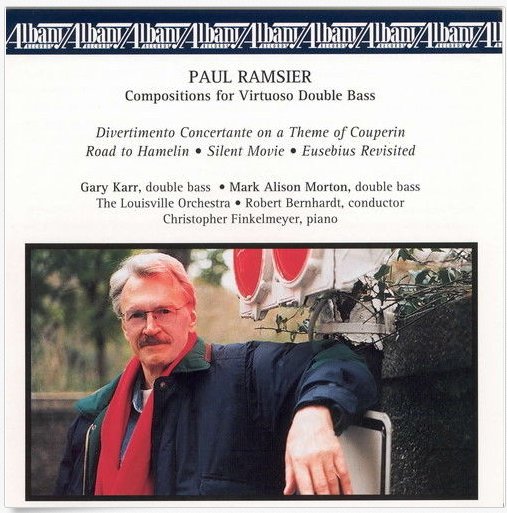

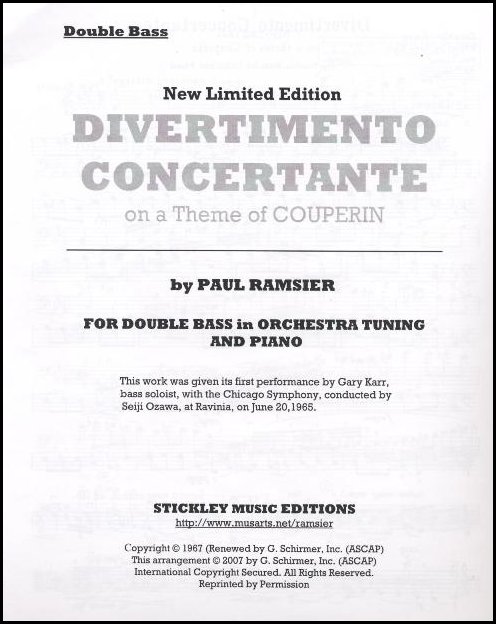

website. BD] Ramsier’s output includes orchestral, opera, choral, instrumental and chamber works, but his best known contribution to contemporary music is his body of work for the double bass, which has established him as a major figure in the development of the instrument. His renowned double bass compositions include four works with orchestra beginning with the landmark Divertimento Concertante on a Theme of Couperin. This and two subsequent works, Road to Hamelin and Eusebius Revisited have since become bass standards, and are regarded as the most performed compositions for bass and orchestra since l965. There have been well over 150 such performances with orchestral ensembles including the Chicago Symphony, Toronto Symphony, London Symphony, Hong Kong Philharmonic, Melbourne (Australia) Symphony, Rotterdam Philharmonic, Puerto Rico Symphony, Montevideo Symphony, Minnesota Orchestra, Indianapolis Symphony, Kansas City Symphony, Columbus Symphony, Atlanta Symphony, Israel Sinfonia, Louisville Orchestra, Istanbul State Symphony, Florida Symphony, Atlantic Symphony, Basel Symphony, Zurich Chamber Orchestra, McGill Chamber Orchestra, and I Musici de Montreal. Among his other compositions, a one-act opera, The Man on the Bearskin Rug, is well known and frequently performed, as is another large bass work, Silent Movie for solo bass with strings and harp. Ramsier taught composition at New York University and the Ohio State University. After earning a Ph.D., he turned his attention to the study of psychoanalysis, and has since pursued a double career in psychotherapy and musical composition. Dr. Ramsier composes, and practices psychotherapy, in Florida. His practice includes many creative and performing artists. |

PR: I’ve been doing

this work for the

double bass for so long that I haven’t thought about that particular

question for a while, because it seems such an organic thing

for me to do at this point.

PR: I’ve been doing

this work for the

double bass for so long that I haven’t thought about that particular

question for a while, because it seems such an organic thing

for me to do at this point. PR: It came out that

way. It’s certainly not

supposed to sound difficult, and Gary plays it with such ease, or

apparently with such ease that it seems to be without any kind of

complications for him. At this point, it’s not, but it took a

good many years before other bassists would tackle it. Some of

them are his students. He’s really very generous and imparting as

a teacher, but he knows. Lately there have been a number of

performers that are tackling that piece, and wrote to him. Two of

them are in Chicago. One is Jeff Bradetich, who is teaching at

Northwestern and has developed the International Society of Bassists to

a

very large degree, and Carol Hart, who came over a few months ago

to play the piece for me. I was very impressed with Carol.

She’s doing graduate work at Northwestern.

PR: It came out that

way. It’s certainly not

supposed to sound difficult, and Gary plays it with such ease, or

apparently with such ease that it seems to be without any kind of

complications for him. At this point, it’s not, but it took a

good many years before other bassists would tackle it. Some of

them are his students. He’s really very generous and imparting as

a teacher, but he knows. Lately there have been a number of

performers that are tackling that piece, and wrote to him. Two of

them are in Chicago. One is Jeff Bradetich, who is teaching at

Northwestern and has developed the International Society of Bassists to

a

very large degree, and Carol Hart, who came over a few months ago

to play the piece for me. I was very impressed with Carol.

She’s doing graduate work at Northwestern. BD: Well, where is

the balance?

BD: Well, where is

the balance? PR: Of course every

person is quite different,

but there are about three different types of problems that I

encounter. I have almost touched on it before, but I might go

into

that in a slightly different way. One would be the artist who

is perhaps not going to get performed or have their work shown. I

help them with how to deal

with that. The next might be the artist that has

recognition but absolutely no income. Strange as that may seem,

there is an assumption that if you’re famous in this country, that you

automatically make a living and a pretty good one. But that’s not

always the case, especially in the case of composers and poets,

certainly. Painters, by the way, tend to go in a different

category. If they get any recognition at all, they might be able

to make their living as painters because the

work is realized and it has some value on the market if the artist

becomes even half way well known. This is

not true for a composer who may have to teach or might have to

conduct. This is not full-time composing, when somebody has to

teach or conduct. So there is

certainly a group of artists that have some recognition but barely

enough money to live on. That’s a

terrible thing in our society, and dealing with that is

difficult. One might say they’re in the category of the poor and

famous. [Both laugh] The third category would be creative

artists or even performing artists who have attained a good

deal of recognition, and are obsessed, so to speak, with how to

maintain that. A painter, for example, might find that as long as

they supply the point of view that the gallery wants, everything is

fine. But what if something organic in them says,

“Well, hey, let’s try something else.” How do they handle

that? So that’s certainly a problem. Another problem is

the sense that many artists have that if they are not successful

they’re somehow looked down upon, and I think that’s quite true.

When they’re not successful they’re seen as perhaps crazy or weird

or bitter. When they become successful, they’re

suddenly delightfully eccentric.

PR: Of course every

person is quite different,

but there are about three different types of problems that I

encounter. I have almost touched on it before, but I might go

into

that in a slightly different way. One would be the artist who

is perhaps not going to get performed or have their work shown. I

help them with how to deal

with that. The next might be the artist that has

recognition but absolutely no income. Strange as that may seem,

there is an assumption that if you’re famous in this country, that you

automatically make a living and a pretty good one. But that’s not

always the case, especially in the case of composers and poets,

certainly. Painters, by the way, tend to go in a different

category. If they get any recognition at all, they might be able

to make their living as painters because the

work is realized and it has some value on the market if the artist

becomes even half way well known. This is

not true for a composer who may have to teach or might have to

conduct. This is not full-time composing, when somebody has to

teach or conduct. So there is

certainly a group of artists that have some recognition but barely

enough money to live on. That’s a

terrible thing in our society, and dealing with that is

difficult. One might say they’re in the category of the poor and

famous. [Both laugh] The third category would be creative

artists or even performing artists who have attained a good

deal of recognition, and are obsessed, so to speak, with how to

maintain that. A painter, for example, might find that as long as

they supply the point of view that the gallery wants, everything is

fine. But what if something organic in them says,

“Well, hey, let’s try something else.” How do they handle

that? So that’s certainly a problem. Another problem is

the sense that many artists have that if they are not successful

they’re somehow looked down upon, and I think that’s quite true.

When they’re not successful they’re seen as perhaps crazy or weird

or bitter. When they become successful, they’re

suddenly delightfully eccentric. PR: First I would

have to know what

greatness is. Is greatness what I’m told greatness is? Is

Beethoven great? Yes, sure, Beethoven’s great. I picked

Beethoven as an example because I’m not always taken well with

Beethoven. I can say that without too much

apology because Stravinsky didn’t like Beethoven. I had the

privilege of working with Stravinsky when I was a staff pianist at the

New York

City Ballet, many, many years ago. And some great music became

great for me when I was able to analyze it as a music student, and some

didn’t. I can only say whatever greatness is appeals to me

on an emotional level. That’s all. The intellectual, per

se, is not for me. It’s fine if it’s for somebody

else. For example, I’ve always

liked Ravel, but when I hear it, it comes to me as such a fresh

expression, such incredible perfection, that I think, “How could a mere

mortal have written this?” Then I think, “Why did it take so

long for Ravel to catch on?” A lot of scholars have been just

paying him

lip service until lately, and maybe they are still, but one

certainly hears it a lot. For some reason, it’s taken this long

for it

to communicate. It’s ravishing, and everything that I hear of his

is. So for me that’s so incredibly great. Now somebody

else might say that Wagner is incredibly great, and I would

agree. I sat at the Metropolitan and heard a number of Wagner

operas, and felt that my life has been changed, but I was never sure

whether it was

for the better! [Laughs] I can’t tell you why, and I’m not

knocking Wagner, but it doesn’t matter because he’s

already got plenty of supporters.

PR: First I would

have to know what

greatness is. Is greatness what I’m told greatness is? Is

Beethoven great? Yes, sure, Beethoven’s great. I picked

Beethoven as an example because I’m not always taken well with

Beethoven. I can say that without too much

apology because Stravinsky didn’t like Beethoven. I had the

privilege of working with Stravinsky when I was a staff pianist at the

New York

City Ballet, many, many years ago. And some great music became

great for me when I was able to analyze it as a music student, and some

didn’t. I can only say whatever greatness is appeals to me

on an emotional level. That’s all. The intellectual, per

se, is not for me. It’s fine if it’s for somebody

else. For example, I’ve always

liked Ravel, but when I hear it, it comes to me as such a fresh

expression, such incredible perfection, that I think, “How could a mere

mortal have written this?” Then I think, “Why did it take so

long for Ravel to catch on?” A lot of scholars have been just

paying him

lip service until lately, and maybe they are still, but one

certainly hears it a lot. For some reason, it’s taken this long

for it

to communicate. It’s ravishing, and everything that I hear of his

is. So for me that’s so incredibly great. Now somebody

else might say that Wagner is incredibly great, and I would

agree. I sat at the Metropolitan and heard a number of Wagner

operas, and felt that my life has been changed, but I was never sure

whether it was

for the better! [Laughs] I can’t tell you why, and I’m not

knocking Wagner, but it doesn’t matter because he’s

already got plenty of supporters.

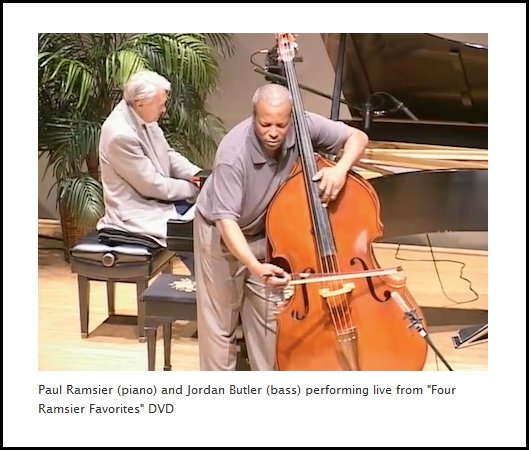

© 1988 Bruce Duffie

This conversation was recorded at his home in New York City on

March 26, 1988. Portions (along with recordings) were broadcast

on WNIB in 1997.

This transcription was made in 2015, and posted on this

website

at that time.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website, click here.

Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM, as well as on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio.

You are invited to visit his website for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.