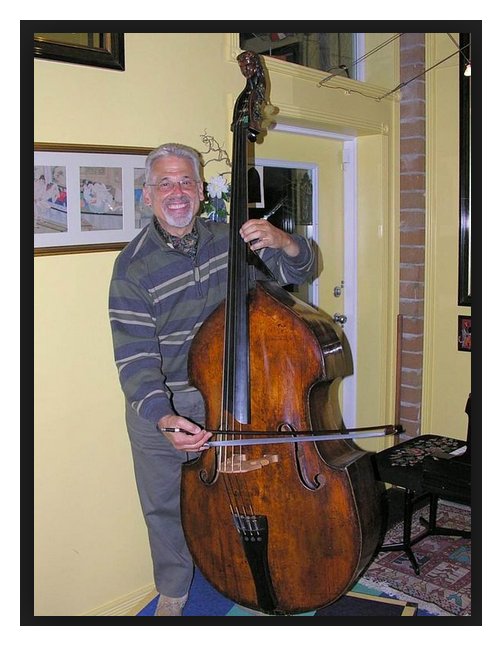

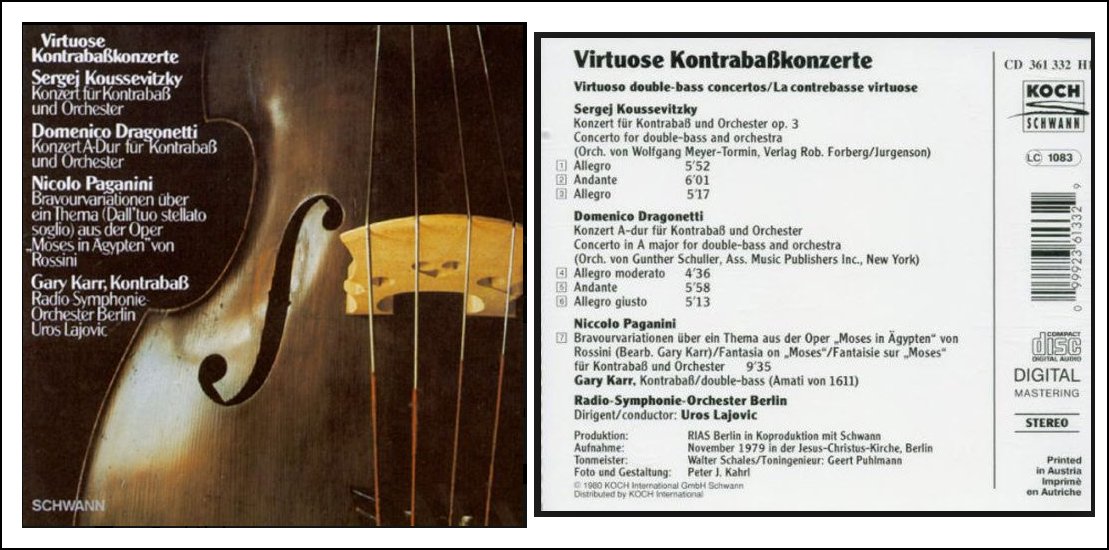

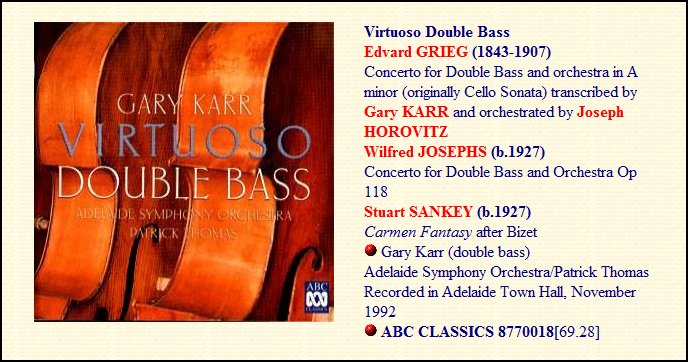

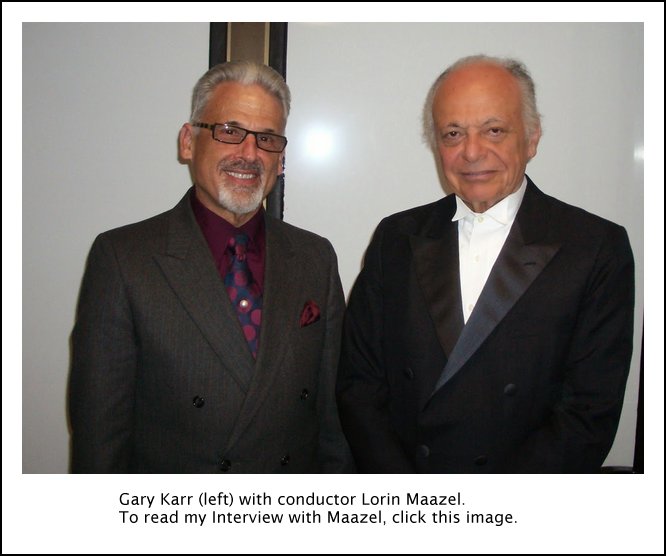

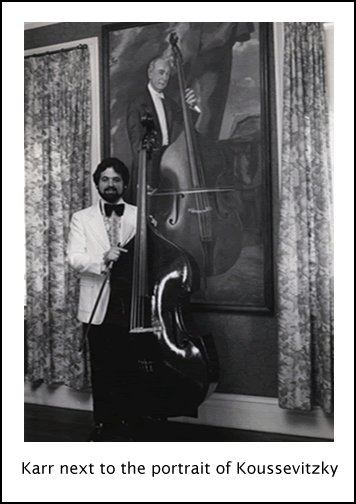

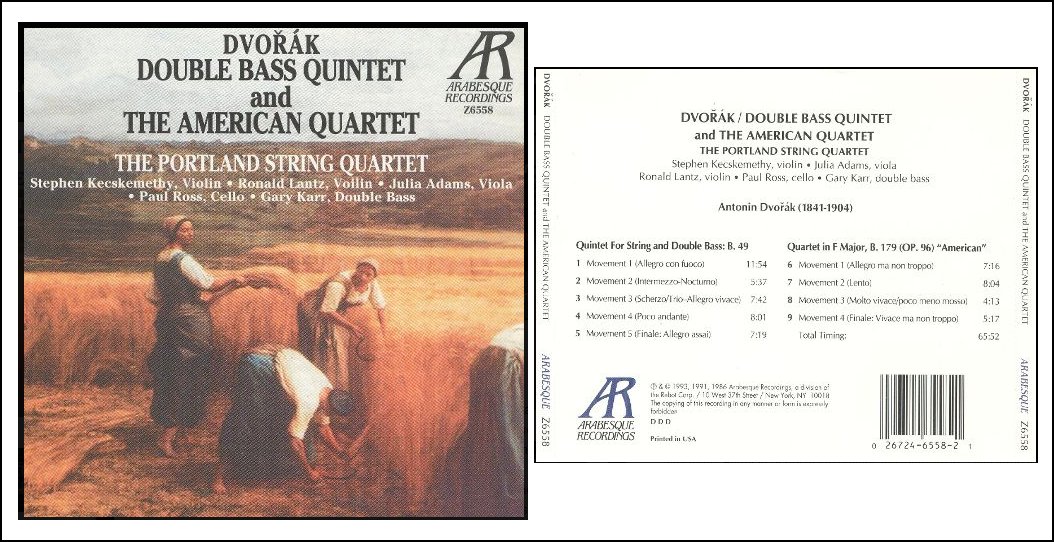

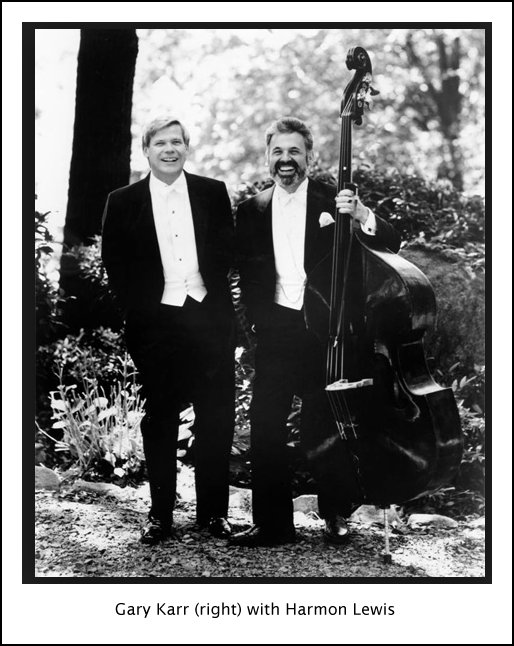

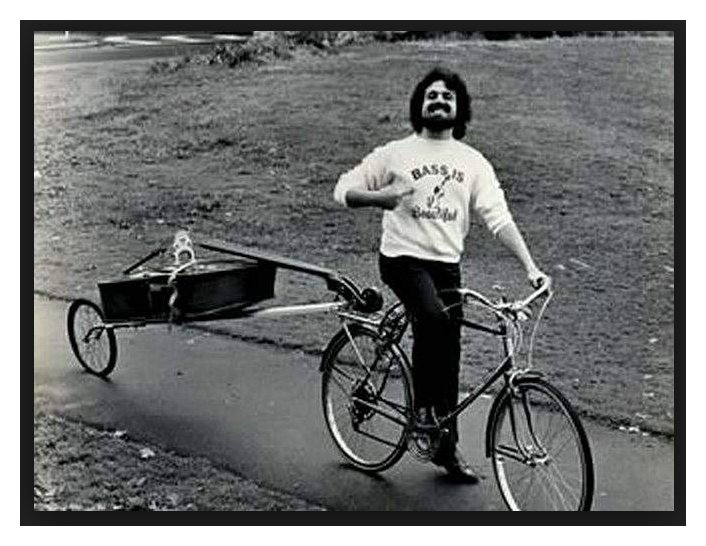

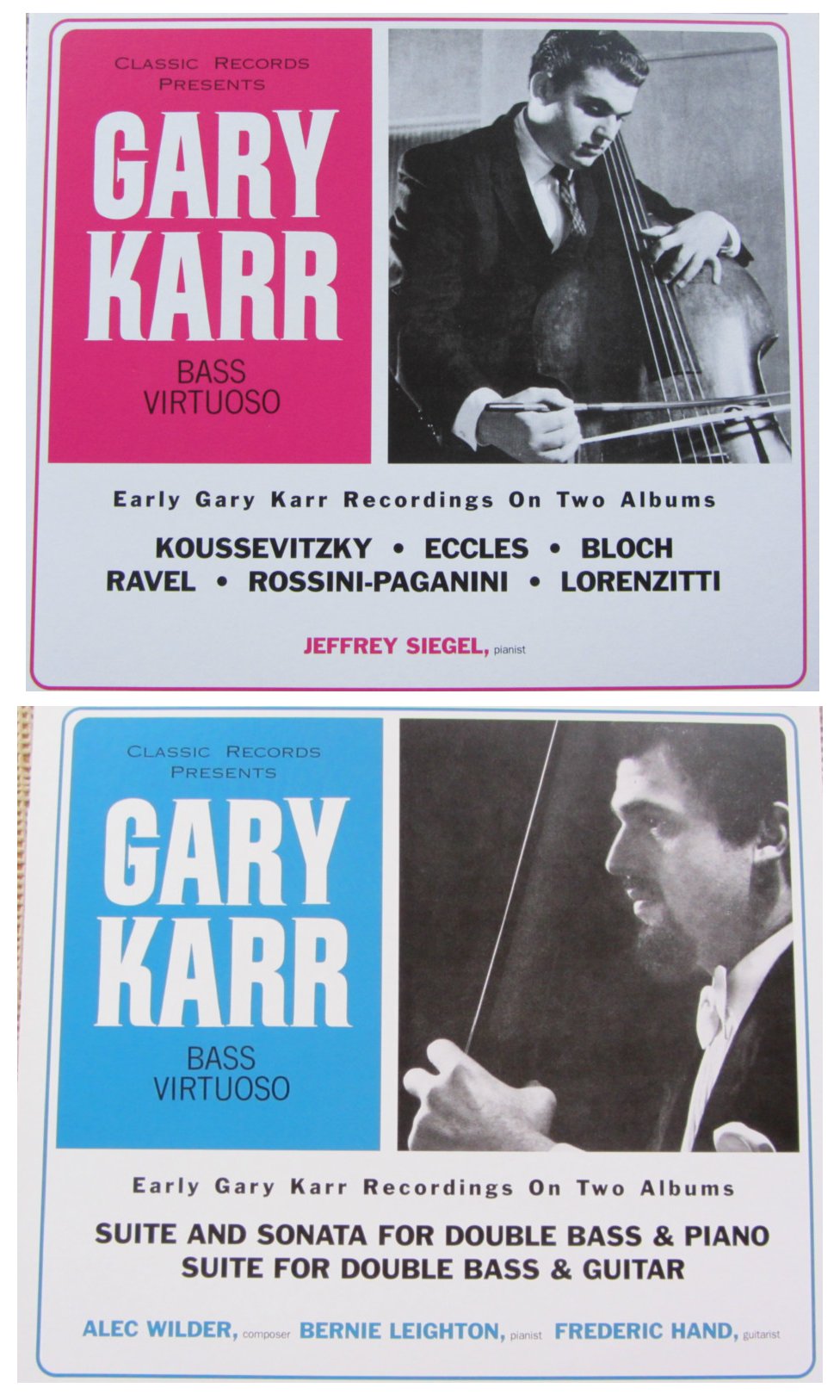

Gary (Michael) Karr. Bassist, teacher, writer, born Los Angeles 20 Nov 1941, naturalized Canadian 1997; honorary D MUS (Victoria) 2005. Karr came from a family of seven generations of bass players, and despite their general lack of encouragement in pursuing the profession, he became the world's first double bassist to have a full-time solo performing career on the instrument. He began his studies with the Russian bassist Uda Demenstein, and subsequently studied with Herman Reinshagen (University of Southern California), Warren Benfield (Northwestern University), and Stuart Sankey (The Juilliard School). Other teachers and mentors included cellists Gabor Rejto, Zara Nelsova, and Leonard Rose, pianist Leonard Shure, conductor Alfredo Antonini, and mezzo-soprano Jennie Tourel. Karr adopted a very vocal approach to the bass. As a student at The Juilliard School he subbed in the Metropolitan Opera Orchestra and had a first-hand opportunity to observe world-class singers. Karr began his solo career with the Chicago Little Symphony under Thor Johnson in 1961, and appeared with the New York Philharmonic Orchestra in Leonard Bernstein's Young People's Concerts at Carnegie Hall in 1962. Karr enjoyed a 40-year virtuoso career (1961-2001), appearing as a soloist with major orchestras all over the world including the Chicago Symphony, the London Philharmonic (England), the Orchestre Symphonique de Montréal, the Hong Kong Philharmonic and the Jerusalem Symphony (Israel). He has been featured in videos on the British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC), CBS, and the CBC in a 12-week TV series called Gary Karr and His Friends (1973). Karr has had a long-time collaboration with pianist-organist-harpsichordist Harmon Lewis. The Karr-Lewis Duo has performed internationally in recitals and at music festivals such as the Menuhin Festival in Gstaad (Switzerland), the Edinburgh Festival, the Bergen Festival (Norway) and the Victoria International Festival in British Columbia. Karr received a prized Bronze Medal from the Rosa Ponselle Foundation (c 1992), recognizing him as an outstanding lyrical musician. He was awarded the Artist-Teacher of the Year Award from the American String Teachers Association (ASTA) in 1997. In 1967, he founded the International Society of Double Bassists (ISB), and this organization awarded him its Distinguished Achievement Award (1995), and Distinguished Teacher Award (2001). In 2001 Karr played his farewell concert at the ISB Convention in Indianapolis.  Not long after his New York debut recital (1962), Karr was given a treasured 1611 Amati double bass by Olga Koussevitsky, which had belonged to her late husband Serge (bass virtuoso and conductor 1874-1951). Karr subsequently (1983) established the non-profit Karr Doublebass Foundation to loan instruments to deserving young musicians selected by competition. In 1995, Karr commissioned a new bass from the Victoria luthier James Ham, an instrument made entirely of wood from BC. In 2004, Karr gifted the Amati, which on investigation turned out to be of French origin (c. 1800) and since has been known as the Karr-Koussevitsky bass, to the ISB. An alumnus of The Juilliard School, Gary soon accepted a teaching position at North Carolina School of the Arts headed by Vittorio Giannini. He has since held US faculty appointments at The Juilliard School, Yale University, Indiana University, the New England Conservatory of Music, and the University of Wisconsin. In the 1970s he served on the Canada Council's Artist Advisory Panel for three years, while teaching at Dalhousie University (1972-1977) and at public schools in Halifax. From 1972 to 1994, Karr was on faculty at the Johannesen International School of the Arts, and in 1996 he started KarrKamp, an intensive month-long summer course for bassists held at the University of Victoria which has attracted bass players of all ages and levels from throughout the world. Karr has produced numerous educational method books and videos on the technical aspects of playing the bass, and has written articles for musical journals. Composers who have written works for Karr include Vittorio Giannini, and Gunther Schuller (Concerto for Double Bass and Orchestra, 1968) and he has commissioned works by American composers Lalo Shifrin and John Downey, and Canadians Alexander Brott and Dennis Farrell (Suite Catholique, 1973), among others. Although mainly a classical performer, Karr has played all sorts of music on the bass, including many of his own arrangements and transcriptions. He has played with most great jazz bassists, and appeared with Oscar Peterson and his bassist, Niels-Henning Orsted Pedersen, on a BBC TV special. In 2000, at an event for Music of Remembrance (MOR, a Seattle-based chamber music organization dedicated to preserving the musical legacy of Holocaust musicians), Karr performed the world premiere of Lori Laitman's Holocaust 1944 for baritone and double bass written especially for him. Karr joined the MOR Advisory Board in 2000. Karr officially retired to Victoria, BC in 2001, where he has continued to teach at the Victoria Summer Music Festival, write for musical journals, perform chamber music, and fundraise for musical events. He has another unusual bass, from the Interlochen Center for the Arts in Michigan -- one made of aluminum that he has used as a decoration in his rose garden in Victoria. -- From the Canadian

Encyclopedia (text only - photo added for this website

presentation)

-- Note: Names which are links on this webpage refer to my Interviews elsewhere on my website. BD |

BD: Was that

because the pitch was more in the

mid-range of the bass, as opposed to the lower range of the cello?

BD: Was that

because the pitch was more in the

mid-range of the bass, as opposed to the lower range of the cello?

The Karr-Kousevitzky bass, or Amati bass, is a famous double bass previously belonging to Serge Koussevitzky and Gary Karr. It is now [2016] generally referred to as the Karr-Koussevitzky rather than the Amati. Until recently, the bass had been attributed to the Amati brothers, but now it is generally believed to have its origins in France. It is renowned for its tonal quality in solo music, but is considered to be difficult to play. The origins of the bass have long been subject to speculation. Although nothing is known of the instrument before 1901, Koussevitzky reported having acquired it from a French dealer. The bass was originally thought to have been made in 1611 by Antonio and Girolamo Amati. However, recent studies suggest a French origin and a fabrication date closer to 1800. The studies consider style of construction and feature proportions to identify a region and date. Growth ring analysis further confirmed the more recent date. |

BD: Do you ever play a five

string bass?

BD: Do you ever play a five

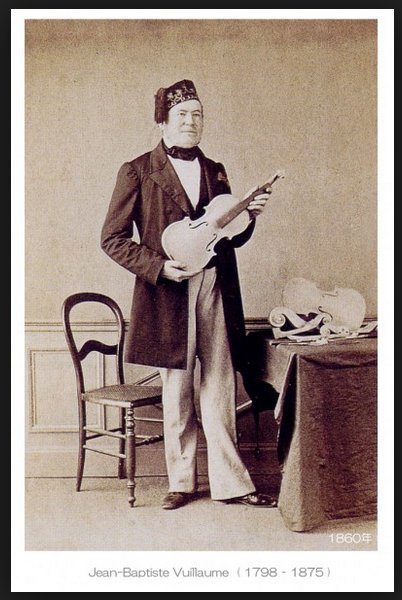

string bass?Jean-Baptiste Vuillaume (7

October 1798 – 19 March 1875) was a French

luthier and winner of many awards. He made over 3,000 instruments and

was a businessman and an inventor. He was born in Mirecourt,

where his

father and grandfather were luthiers. Vuillaume moved to Paris in 1818 to work for

François Chanot. In 1821,

he joined the workshop of Simon Lété,

François-Louis Pique's

son-in-law, at Rue Pavée St. Sauveur. He became his partner, and

in

1825 settled in the Rue Croix des Petits-Champs under the name of

"Lété

et Vuillaume". His first labels are dated 1823. In 1827, at the height

of the Neo-Gothic period, he started to make imitations of old

instruments, some copies were undetectable. Vuillaume moved to Paris in 1818 to work for

François Chanot. In 1821,

he joined the workshop of Simon Lété,

François-Louis Pique's

son-in-law, at Rue Pavée St. Sauveur. He became his partner, and

in

1825 settled in the Rue Croix des Petits-Champs under the name of

"Lété

et Vuillaume". His first labels are dated 1823. In 1827, at the height

of the Neo-Gothic period, he started to make imitations of old

instruments, some copies were undetectable.In 1827, he won a silver medal at the Paris Universal Exhibition, and in 1828, he started his own business at 46 Rue Croix des Petits-Champs. His workshop became the most important in Paris, and within twenty years it led Europe. A major factor in his success was his 1855 purchase of 144 instruments made by the Italian masters for 80,000 francs, from the heirs of Luigi Tarisio, an Italian tradesman. These included the Messiah Stradivarius and 24 other Stradivari. In 1858, in order to avoid Paris customs duty on wood imports, he moved to Rue Pierre Demours near the Ternes, outside Paris. He was at the height of success, having won various gold medals in the competitions of the Paris Universal Exhibitions in 1839, 1844, and 1855, the Council Medal in London in 1851, and in that same year, the Legion of Honour. A maker of more than 3,000 instruments—almost all of which are numbered—and a fine tradesman, Vuillaume was also a gifted inventor, as his research in collaboration with the acoustics expert Savart demonstrates. As an innovator, he developed many new instruments and mechanisms, most notably a large viola which he called a "contralto", and the three-string Octobass (1849–51), a huge triple bass standing 3.48 metres high. He also created the hollow steel bow (particularly appreciated by Charles de Bériot, among others), and the 'self-rehairing' bow. For the latter, the hair purchased in prepared hanks could be inserted by the player in the time it takes to change a string, and was tightened or loosened by a simple mechanism inside the frog. The frog itself was fixed to the stick, and the balance of the bow thus remained constant when the hair stretched with use. He also designed a round-edged frog mounted to the butt by means of a recessed track, which he encouraged his bowmakers to use. Other details of craft, however, make it possible to identify the actual maker of many Vuillaume bows. The bows are stamped, often rather faintly, either "vuillaume à paris" or "j.b. vuillaume". Other innovations include the insertion of Stanhopes in the eye of the frogs of his bows, a kind of mute (the pédale sourdine) and several machines, including one for manufacturing gut strings of perfectly equal thickness. Vuillaume was an innovative violin maker and restorer, and a tradesman who traveled all of Europe in search of instruments. Due to this fact, most instruments by the great Italian violin makers passed through his workshop. Vuillaume then made accurate measurements of their dimensions and made copies of them. He drew his inspiration from two violin makers and their instruments: Antonio Stradivari and his "Le Messie" (Messiah), and Giuseppe Guarneri del Gesù and his "Il Cannone" which belonged to Niccolò Paganini. Others such as Maggini, Da Salò and Nicola Amati were also imitated, but to a lesser extent. |

BD:

Is it famous because Amati made it, or is

it famous because Koussevitzky played it?

BD:

Is it famous because Amati made it, or is

it famous because Koussevitzky played it? GK:

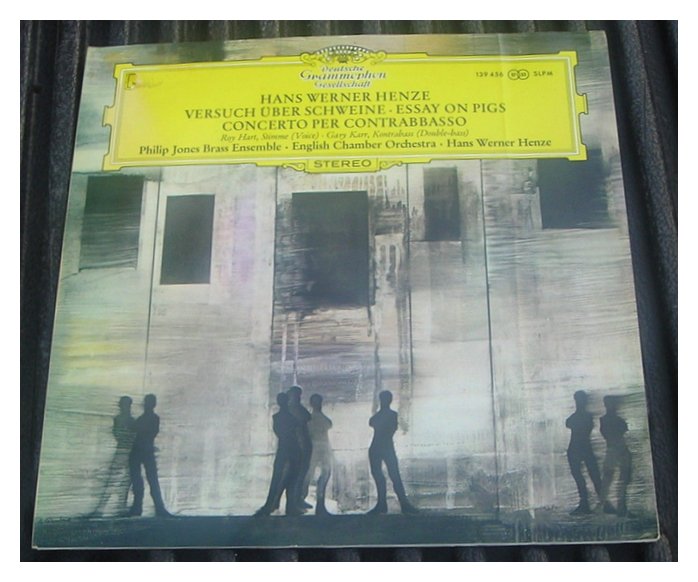

Yes. For instance, the reason I went to Hans Werner Henze to

commission his concerto was that he

had done his Elegy for Young Lovers

in New York. I was in the

orchestra at the Julliard School when they premiered this, and I fell

in love with his music. I thought, “He’s

just written

this, so let me reach him while he’s

hot.” I said, “I want something like that

for the bass.” It

didn’t turn out to be as lyrical as I would like, quite frankly,

because he had already moved in a new mode at that time. What

I got was a kind of intricate piece of chamber music that’s very

complicated. But the Koussevitzky Foundation commissioned Gunther

Schuller to write a concerto for

me, and because I didn’t go to him, he had preconceived ideas.

What he wrote was a pointillistic piece without a held

note, and there is no piece of music that is as opposite to my

character and nature and everything I believe in than that piece.

GK:

Yes. For instance, the reason I went to Hans Werner Henze to

commission his concerto was that he

had done his Elegy for Young Lovers

in New York. I was in the

orchestra at the Julliard School when they premiered this, and I fell

in love with his music. I thought, “He’s

just written

this, so let me reach him while he’s

hot.” I said, “I want something like that

for the bass.” It

didn’t turn out to be as lyrical as I would like, quite frankly,

because he had already moved in a new mode at that time. What

I got was a kind of intricate piece of chamber music that’s very

complicated. But the Koussevitzky Foundation commissioned Gunther

Schuller to write a concerto for

me, and because I didn’t go to him, he had preconceived ideas.

What he wrote was a pointillistic piece without a held

note, and there is no piece of music that is as opposite to my

character and nature and everything I believe in than that piece. GK: It’s so funny that you put

it on those

terms, because that is exactly how I think of the bass. The bass,

to me, is an opera singer. The bass, to me, is the voice that I

wish

I were. I am a frustrated singer. Obviously, I must be

because I’m a lyricist. I love lyrical lines. I want to

sing. In fact, when I was young I studied singing. I

studied singing with Jenny Tourel, and I got up and sang

for an audience because I wanted to evoke in the audience the same kind

of reaction I had hearing a singer when I was very young. I was

very emotionally moved by this, and I wanted to do that same thing and

get

that same kind of response. So I sang to an audience and

everybody cried — for all the wrong

reasons. I had such a horrible voice, nobody could stand

it. So the bass became my

voice. When I play the bass, I do not think of it as an

instrument. I think of it as a voice. I play into it as

though I were breathing into the bass and the sounds are coming

out. I think of it more as a voice than I would be thinking of a

voice if I were actually singing myself. If I were to

sing I would be a bass.

GK: It’s so funny that you put

it on those

terms, because that is exactly how I think of the bass. The bass,

to me, is an opera singer. The bass, to me, is the voice that I

wish

I were. I am a frustrated singer. Obviously, I must be

because I’m a lyricist. I love lyrical lines. I want to

sing. In fact, when I was young I studied singing. I

studied singing with Jenny Tourel, and I got up and sang

for an audience because I wanted to evoke in the audience the same kind

of reaction I had hearing a singer when I was very young. I was

very emotionally moved by this, and I wanted to do that same thing and

get

that same kind of response. So I sang to an audience and

everybody cried — for all the wrong

reasons. I had such a horrible voice, nobody could stand

it. So the bass became my

voice. When I play the bass, I do not think of it as an

instrument. I think of it as a voice. I play into it as

though I were breathing into the bass and the sounds are coming

out. I think of it more as a voice than I would be thinking of a

voice if I were actually singing myself. If I were to

sing I would be a bass.

BD: So in your

performances, are you striving to make the double bass an equal to the

violin and the clarinet and everything else?

BD: So in your

performances, are you striving to make the double bass an equal to the

violin and the clarinet and everything else?| When Mark Levinson left Madrigal (and his name) back in the mid 1980's, his goal was to create audio equipment that surpassed anything that had been done before (including the equipment that still bares his name), thus Cello Ltd. was born. Working with a team of engineers, Cello Ltd. created a line of amplifiers, pre-amplifiers, digital to analog converters and speakers that are still considered to be some of the finest ever produced. As the reputation of the Cello equipment grew, the company was devoting more and more time to implementing systems for clients, working with partners to design complete systems that performed to the level of the Cello components. This eventually lead to the formation of Cello Music & Film, a division of the company dedicated to the design and implementation of world class audio and video environments. (From the company website.) |

BD: So it’s the

musical equivalent of desktop

publishing?

BD: So it’s the

musical equivalent of desktop

publishing? BD: What an offer!

BD: What an offer!

© 1993 Bruce Duffie

This conversation was recorded in Chicago on December 13,

1993. Portions were broadcast on WNIB the following

year,

and again in 1996.

This transcription was made in 2016, and posted on this

website

at that time.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website, click here.

Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM, as well as on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio.

You are invited to visit his website for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.