CONVERSATION

PIECE:

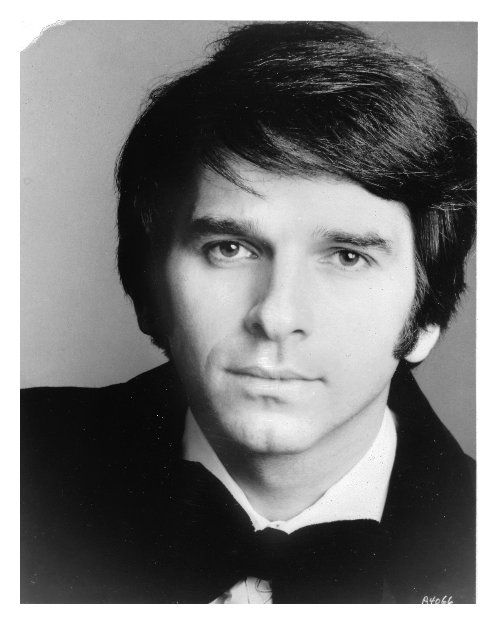

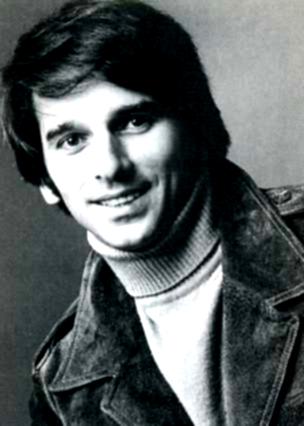

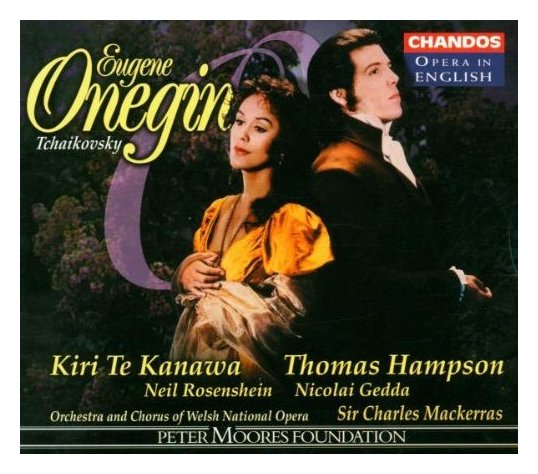

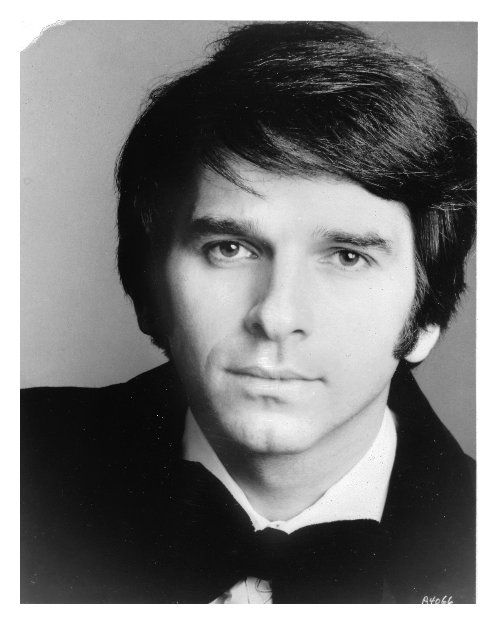

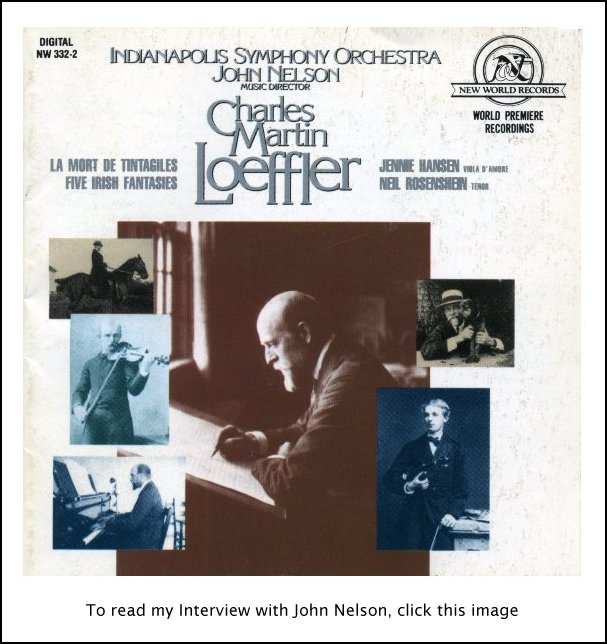

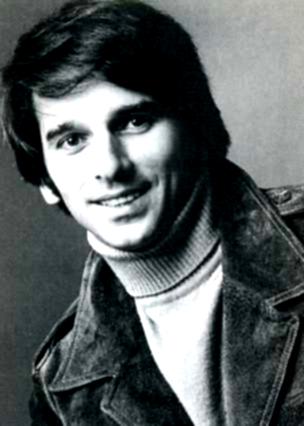

NEIL ROSENSHEIN

By Bruce Duffie

As regular readers of these pages are aware, I have

had the pleasure and privilege of meeting and interviewing many of the

musicians who traipse ’round the world

performing concerts and operas

in cities and towns with companies great and small. Naturally, I

try to keep up with much of what’s going on by subscribing to many of

the critical magazines with the words “opera” or “music” or “records”

in their titles. Each issue of every one provides me with the

joy of seeing pictures or reading reviews of any number of my

guests. Several times, I’ve been airing a conversation on WNIB

during our Sunday Evening Opera, and reading about that person in the

New York Times Arts & Leisure

Section of the same date.

Great minds think alike…

Anyway, after transcribing the conversation you’re

about to read, I was gathering my thoughts on these introductory

paragraphs (while reading another of the magazines) and there on the

page is Neil Rosenshein as Peter Grimes! This is a role he had

mentioned he wanted to do, and under the picture, the reviewer said his

“shattering reading” of the part was “gripping.” Chalk up another

success for this guest.

Tenor Neil Rosenshein has traveled widely, and in

Chicago he’s portrayed Verdi’s Don Carlo, as well as lighter roles in

Die Fledermaus and The Bartered Bride. It was on

one of those

trips that we chatted between the performances, and we pick up the

conversation with a surprising story…

Neil Rosenshein: The

Australian Opera is a fantastic

company. There’s only 16 million people in the whole country, and

it’s the largest opera-going public per capita in the world. I

had signed a contract to go there and sing, and the Christmas before my

debut I got a Christmas card from the company. All those people

signed it and said they couldn’t wait for me to come so they could

meet me and make music together. When I got there, it was just as

I thought it would be – the people were very friendly and very

professional. It’s a real company in the sense that they don’t

bring in that many stars from outside. There are maybe 7 or 8 a

year, so I felt a kind of belonging, especially since I’m not a member

of any company. So I go there semi-regularly. Their

TV-film of Bohème that

I was in won an Emmy award.

Bruce Duffie: Do you like

the

life of a wandering minstrel?

Bruce Duffie: Do you like

the

life of a wandering minstrel?

NR: In some ways I do,

and in ways that I didn’t I’ve gotten used

to.

BD: Do you have to

acclimate to each new surrounding wherever you

go?

NR: Yes I do. It

used to be very difficult and now it’s

much less difficult. You develop a discipline for your work and

this is really part of the work. If you don’t find a way to relax

and enjoy this part of your life, it will not be much pleasure because

you spend a lot of time alone and in cities you don’t know.

BD: Is it fun to learn

new cities?

NR: Somewhat. Some

cities are fun to learn – the ones you

can walk around in are the ones you learn. If you have to drive

around, you don’t get around as much, and don’t really learn

them.

Here in Chicago I know the downtown area, but I can’t say I know the

city. I don’t know Los Angeles, but I’ve been there for

concerts. However, San Francisco, New York, Boston, Washington,

Venice, Rome and Paris are ones I can get around in, and it’s easier to

know them. I love them.

BD: Does the reaction or

acceptance by the public have anything

to do with whether you like a city or not?

NR: I think so.

Basically, whether the public accepts you

or not is up to the artist. Even if you don’t get them the first

time, if you’re generous in your expression and do your job with

integrity, you’ll get the public. By the same token, if the opera

doesn’t work, it’s probably not Verdi’s fault, it’s our fault.

Either we’re not giving enough of ourselves, or we’re not spending

enough time in preparation to understand what we’re doing or what we’re

asked to do by the composer. Responsibility lies with yourself.

BD: Is there any chance

of giving too much on occasion?

NR: In different senses

there are ways. You could give too

much vocally and over-sing, or you could give too much emotionally and

lose your voice and not really express the emotion of the

composer by only expressing your own emotion, but that’s basically

indulgence. If you indulge, you have to pay for it, just as you

do if you over-eat or over-drink. However, the greatest freedom

is within a discipline. With a fine vocal technique, when you

prepare a role you can go as far as you can emotionally and

musically. You can go incredibly far with abandon as long as you

start within that discipline.

BD: So you work

painstakingly hard on every little facet during

rehearsals, and then let yourself go during the performances?

NR: Yes, exactly.

There’s a stack of music over there that

I’m working on for performances a year and a half away. You need

a flexible approach because they’re complicated operas. If you

want to give a profound performance, one approach is to learn the music

thoroughly and also the nuances of the text. Going back to the

original play might or might not be a help, but I throw myself

into it and become intoxicated with the beauty of it. You also

need to understand each phrase and know where the accents go and

understand the style.

BD: Is there any chance

that you might over-analyze it?

NR: That’s very

interesting, and yes you can. You get to a

point during your study when the piece seems to deaden. That can

happen in rehearsals, too. One has to come full-circle.

First, you sing through the piece without knowing very much about

it. Then you study it for a year and a half, and you finally come

back to where you started with 50% or 60% or 70% of what you did the

first time, except that now you’re sure it’s right. With that

attitude, you can give it much more, plus all the nuances of what

you’ve learned. Your instinct is the basis of it, but the rest

has to be laid on top.

*

* *

* *

BD: You are asked to sing

many roles. How do you decide

which you will accept and which you’ll put off for awhile?

NR: There is a kind of logic to

your repertoire. One has to

look not at how high the role is, but what the weight of it is – the

tessitura and also the extremes. Some roles have lots of high D’s

or E-flats, and I couldn’t do that. Others don’t

have the high notes but sit lower and pull the voice down. There

are a number of things you take into consideration. I’m very

lucky now because people offer me everything from the ridiculous to the

sublime, so it’s up to me and to my advisors, my managers and agents

who are really colleagues. We really work these things out

together, but one decides on a role if you really love it.

However, if you don’t love it, that might be simply because you don’t

know it as well, so when I’m asked what my favorite role is, usually

it’s the role I’m doing then because you get more excited and more

intimate with it this week because you’re doing it. However, when

deciding on roles, I think it’s better to know the weight of your

voice, then take off 15% and sing that repertoire. Too often

singers will go up 15% rather than opting to be conservative and stay

vocally healthy. Also, when you have control of your voice, you

have control of your interpretation. You can sing something the

way you feel it should be sung rather than being forced to sing it so

you’ll just manage to stay alive until the finale.

NR: There is a kind of logic to

your repertoire. One has to

look not at how high the role is, but what the weight of it is – the

tessitura and also the extremes. Some roles have lots of high D’s

or E-flats, and I couldn’t do that. Others don’t

have the high notes but sit lower and pull the voice down. There

are a number of things you take into consideration. I’m very

lucky now because people offer me everything from the ridiculous to the

sublime, so it’s up to me and to my advisors, my managers and agents

who are really colleagues. We really work these things out

together, but one decides on a role if you really love it.

However, if you don’t love it, that might be simply because you don’t

know it as well, so when I’m asked what my favorite role is, usually

it’s the role I’m doing then because you get more excited and more

intimate with it this week because you’re doing it. However, when

deciding on roles, I think it’s better to know the weight of your

voice, then take off 15% and sing that repertoire. Too often

singers will go up 15% rather than opting to be conservative and stay

vocally healthy. Also, when you have control of your voice, you

have control of your interpretation. You can sing something the

way you feel it should be sung rather than being forced to sing it so

you’ll just manage to stay alive until the finale.

BD: Do you sing

differently from large houses to small ones?

NR: No, not really.

To some extent a little bit. Some

small houses have terrible acoustics and many large ones have great

acoustics, but in the big ones, you are aware that you can never, not

even for an instant, get off your voice. You can never sing in a

whisper or use an airy tone in a large house. You must stay

completely in the voice. You should in a small house, too, but

once in awhile you can do something subtle either dramatically

because people can see it, or vocally because people can still hear

it. On the other hand, in a big house like Chicago, you don’t

need to make your gestures bigger, but they must be born of great

emotion. You can’t just wander around the stage because you’ll

strangely disappear even though you’re still there. You must

concentrate all the time.

BD: Is this concentration

as the character, or as Neil

Rosenshein portraying the character?

NR: There is a little bit

of Neil Rosenshein in all the

characters. We live according to our experiences, and no matter

how much we read, we still react with a great amount of

ourselves. That’s what makes it unique; that’s what makes my

performances different from anyone else’s. It’s not better or

worse or louder or softer, it’s just me; people like it or don’t

like it, and that’s OK. It simply has to be an honest portrayal

as far as I see him through my own experience and my reading, and my

distillation of all that experience. It’s a great job and a

pleasure to do it. What I’m describing is a great pleasure to do

and incredibly creative. I feel very lucky these days.

BD: Do you ever feel

you’re competing against other tenors who

have sung or recorded these parts?

NR: Totally! That’s

the other side. I’m a competitive

person and this is a competitive business.

BD: Too

competitive?

NR: I’m doing pretty

well, so I guess I’m happy about it.

I’m not really competing so much against tenors of the past because

they were of another age and another style, and I don’t feel the

competition against Domingo, the greatest tenor with whom I share

roles. I have enormous respect for him and his artistry.

But for instance, when I was at Juilliard, the teachers were great,

but it was the other students who kept me on my toes, and I thank God

for the other tenors in my age group, mostly American, because they

force me to always do my absolute best.

BD: Are we building a

tradition of great American tenors like our

tradition of great American baritones?

NR: I think we are, I

think we definitely are.

BD: Do you see your voice

getting bigger and/or heavier as you go

along in your career?

NR: As I’ve been getting

a little bigger and heavier (ahem), the voice has been getting a little

bigger and heavier, too.

It’s also getting freer and has more breadth to it. I plan some

roles that are somewhat heavier in the future, but in a conservative

way. So far, the heaviest roles I do are Don Carlo and

Werther. I’ll be doing Romeo and Don José, and later on

Peter

Grimes. That’s not really a heavier role, but we have a tradition

of knowing Jon

Vickers in the part.

*

* *

* *

BD: Let’s talk a little

about your French roles. Is

Werther the one you’ve sung the most?

NR: Yes. I’ve done

it in Paris…

BD: Is it special to do a

French role in Paris?

NR: To sing a French role in

Paris, yes. To singer Werther

there, definitely. It’s one of the great masterpieces, so it’s

like doing Bohème in

Milano. I was nervous that night,

which was good, but I wasn’t too nervous because I’d sung it in

Amsterdam and at the Met as well as in Sidney and one or two other

places. That one in Australia was a fabulous production by Elijah

Moshinsky with Carlo

Felice Cillario conducting. That was my

favorite, I think. The one in Paris was also wonderful. I

was lucky to have a production of that quality. It is hard to

describe, not a modern one nor a period production. It was set in

a timeless time in between. The public was taken aback when the

curtain went up. The stage was a diagonal row of flowers and

dirt, so the first aria about nature was sung to these roses, and as I

sang, the lights came up stronger and stronger so that at the end they

were like on fire. The more I sang and the more passionate the

music became, the more the flowers seemed to come to life. It was

very effective and the public liked it. The Paris public is very

quick to boo and scream and walk out, so it’s difficult to

please. Someone is booed usually every night, and it doesn’t have

to do with the reality of the evening. It’s just an odd

personality, that public.

NR: To sing a French role in

Paris, yes. To singer Werther

there, definitely. It’s one of the great masterpieces, so it’s

like doing Bohème in

Milano. I was nervous that night,

which was good, but I wasn’t too nervous because I’d sung it in

Amsterdam and at the Met as well as in Sidney and one or two other

places. That one in Australia was a fabulous production by Elijah

Moshinsky with Carlo

Felice Cillario conducting. That was my

favorite, I think. The one in Paris was also wonderful. I

was lucky to have a production of that quality. It is hard to

describe, not a modern one nor a period production. It was set in

a timeless time in between. The public was taken aback when the

curtain went up. The stage was a diagonal row of flowers and

dirt, so the first aria about nature was sung to these roses, and as I

sang, the lights came up stronger and stronger so that at the end they

were like on fire. The more I sang and the more passionate the

music became, the more the flowers seemed to come to life. It was

very effective and the public liked it. The Paris public is very

quick to boo and scream and walk out, so it’s difficult to

please. Someone is booed usually every night, and it doesn’t have

to do with the reality of the evening. It’s just an odd

personality, that public.

BD: Do they come to boo?

NR: Ummm, no, but I think

there are elements that get together

beforehand to decide if someone’s right or not right for a role.

I don’t know if they decided I was right for Werther, but they didn’t

decide that I wasn’t right for it, so I had the evening to convince

them that I was. By the end they were very appreciative and it

was

really great. I was lucky, and sometimes it has more to do with

luck than with art.

BD: What kind of guy is

Werther?

NR: It varies somewhat

from production to production. He’s

a very dark, complicated character. You can approach it in many

different ways, so it’s difficult to say what he’s about exactly.

I don’t approach it any one way. When you have a good producer to

work with, you can change the concept of the production. He can

be madly in love with Charlotte, or he can resent her terribly and

torture her the whole night. There’s no question he is a poet and

a philosopher to some extent.

BD: Is he tortured by

himself?

NR: Yes, he is tortured

completely by himself. He’s the one who sets it up. He

falls in love

with her in the very beginning, but it’s really infatuation. His

first aria is about nature and mother, and when she comes in she

embodies all of it. Werther intellectualizes everything and turns

it around and around and around until he becomes quite mad. But

it’s

hard to say exactly what it’s about because I’ve played it so many

different ways, and all of them honestly. Sometimes he’s hostile,

other times he’s passive and she’s aggressive. There are moments

that give keys to the character one way or another, so you can take

one as being of major importance this time and in the next production

you can take another key as being the most important. For

Charlotte, Werther can represent a freedom from the bondage she’s had

with her family, or she might just want him around because she sees her

very bourgeois life continuing. So it can all change very much

depending on who’s playing the parts. That’s why you can go to

this or any other major opera many times over the years to see

different productions with different conceptions. They can

become completely different pieces. The casts change,

the productions change, and the operas get a completely different

feel. That’s what’s so great about these pieces.

BD: Did Massenet write

well for the tenor voice?

NR: It’s great; I love

his music. He wrote

intelligently; he gives you an opportunity to warm up.

Physically, vocally, technically he wrote in a fabulous way to heat the

public and yourself, and to get the evening rolling. The story

has its

whole hue and color without having to come out and create a big

moment. Especially in Manon,

it starts gently and climbs up and

up and up and reaches its climax at the very last moment. I think

the last act of that opera is the most wonderful –

even better than the last act of Werther.

BD: Sticking with Werther, could Charlotte have been

happy

with him by keeping him as a lover on the side?

NR: There’s the politics

of men and women all the time, and from

my personal point of view, Werther didn’t play it right. If he

wanted her to leave Albert, he didn’t approach it right. Werther

couldn’t; he opens his heart and that was it. He didn’t

have the kind of power over her that he wanted and needed to make his

story succeed. But if he’d succeeded in making her run away with

him, that would have made her impure in his mind. Therefore his

illusion of perfect nature would have been shattered. Werther is

in love with love, and Charlotte is just the vehicle for that love at

the moment.

BD: If there had been no

husband in the story, could Charlotte

and Werther have been happy together?

NR: Perhaps for

awhile…

BD: Was Werther screwy?

NR: You have to be a little bit

screwy to kill yourself.

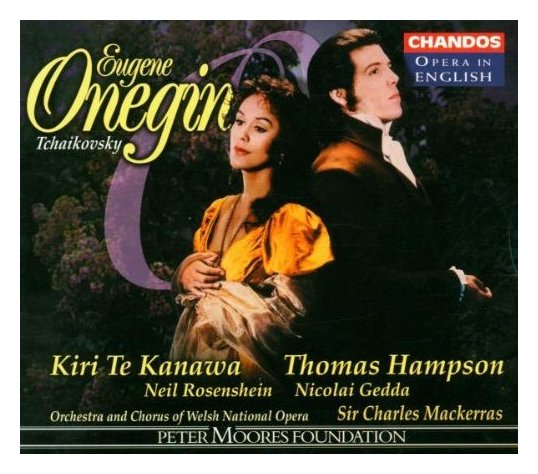

Lensky is younger than Werther and he kills himself – or allows himself

to be killed – but that can be attributed to the

impetuousness of

youth. Lensky cannot be played with great intellect. I play

him as a reasonable young man who gets wrapped up in

circumstance. Werther has a circumstance before we meet him in

the opera. The same with Don Carlos. Who is he?

There’s a lot to him that is put together before we see him. By

reading the Schiller you can get more depth of character. Whether

it is accurate or not, it’s better to have some understanding so you

can make him a whole person onstage.

NR: You have to be a little bit

screwy to kill yourself.

Lensky is younger than Werther and he kills himself – or allows himself

to be killed – but that can be attributed to the

impetuousness of

youth. Lensky cannot be played with great intellect. I play

him as a reasonable young man who gets wrapped up in

circumstance. Werther has a circumstance before we meet him in

the opera. The same with Don Carlos. Who is he?

There’s a lot to him that is put together before we see him. By

reading the Schiller you can get more depth of character. Whether

it is accurate or not, it’s better to have some understanding so you

can make him a whole person onstage.

BD: For the singer, or

for the audience?

NR: If the singer knows

what the character is thinking and

believes it, the audience will get it. That’s why you don’t need

to speak Italian to understand these operas. The audience will

miss some of the subtleties and it’s better to know more about it, but

opera is not “Laverne and Shirley.” You only get out of if what

you put into it. It’s not a passive art form. It

requires audience participation.

BD: What do you expect of

the audience?

NR: Nothing in

particular. Some will be there hanging on

every word looking for each nuance, and others will just want a sensual

experience from the beautiful music and wonderful story. Some

just want the highlights, and others want the minutest details.

BD: OK, then why do you

sing opera?

NR: For the sensual

experience of it and the pleasure of taking

an artistic trip someplace in the world of the theater. If I’m

strong enough, I’ll take the whole public with me. If I believe

in where I’m going and understand and experience this trip, people will

leave the theater having been someplace they couldn’t have gone

otherwise.

BD: Do you ever wish you

could extend the trip beyond the final

curtain?

NR: Sometimes. At

the end of Bohème, I

wonder if the

guys become the middle class that they despise, or stick to their

ideals and become famous artists. I’d also be curious to know how

Rodolfo approaches and appreciates his next love. On the other

hand, it’s not an easy opera to do well, and I’m physically tired at

the

end and I wouldn’t want to have another act to perform.

BD: Are there any easy

operas for you?

NR: Not really because

whatever you do you must do as well as

possible. It requires the same involvement no matter what role

you’re singing. Some might be easier evenings, but you must work

at that same high level. The easier ones are simply shorter and

have fewer dangerous moments, so there’s less pressure.

BD: When you’re deciding

to add a role to your repertoire, do you

count up the dangerous moments?

NR: More important it to

look at your schedule and try to

surround dramatic roles with lyric roles.

BD: Do you sing any comic

roles?

NR: I used to do Almaviva

in The Barber of Seville, but

it’s not

in my repertoire any more. My voice isn’t really dramatic, but

it’s more dramatic than the comic roles are. I love getting

laughs. When the audience applauds at the end of an aria, it’s

nice but perhaps obligatory. Laughs are completely spontaneous,

and a roar from 4,000 people is wonderful. Artistically I’m very

happy not because I’m “The Greatest Star, the Best By Far,” but because

I have the ability now, after years of study, to sing the music I’ve

always wanted to sing in the way I’ve wanted to sing it. That is

such a pleasure that I’d be ashamed to have any kind of

complaint. I sing these great roles in major houses around the

world, but there’s always something more to strive for. You need

a healthy ego to get out there, but that should be the smallest part of

the picture. You shouldn’t be like a child always screaming for

more ice cream. I have great colleagues and I’m very lucky.

=====

===== =====

===== =====

-- -- -- -- -- -- --

===== =====

===== ===== =====

When not behind the microphone at WNIB, or in the balcony of the Opera

House or Orchestra Hall, Bruce Duffie arranges for more

interviews. Next in The Opera

Journal, the British baritone Peter

Glassop as he prepares to celebrate his 65th birthday.

----------------------------------------------------------------------

© 1990 Bruce Duffie

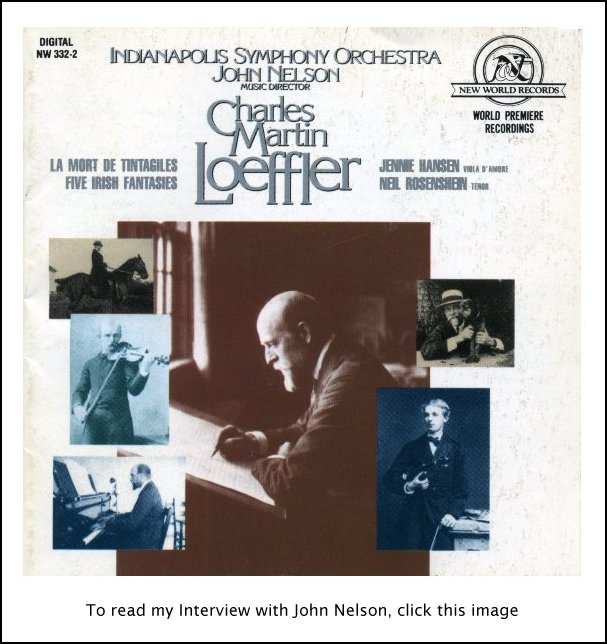

This interview was recorded at his apartment on

January 10, 1990. Sections were used (along with

recordings) on WNIB in 1994 and 1997. It was

transcribed and published in The

Opera Journal in March of 1993. It was slightly re-edited,

the photographs were added, and it posted on this

website in 2012.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been

transcribed and posted on this website, click here.

Award

- winning

broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago

from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of

2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and

journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM,

as well as on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio.

You are invited to visit his website

for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of

other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also

like

to call your attention to the photos and information about his

grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a

century ago. You may also send him E-Mail

with comments, questions and suggestions.

Bruce Duffie: Do you like

the

life of a wandering minstrel?

Bruce Duffie: Do you like

the

life of a wandering minstrel? NR: There is a kind of logic to

your repertoire. One has to

look not at how high the role is, but what the weight of it is – the

tessitura and also the extremes. Some roles have lots of high D’s

or E-flats, and I couldn’t do that. Others don’t

have the high notes but sit lower and pull the voice down. There

are a number of things you take into consideration. I’m very

lucky now because people offer me everything from the ridiculous to the

sublime, so it’s up to me and to my advisors, my managers and agents

who are really colleagues. We really work these things out

together, but one decides on a role if you really love it.

However, if you don’t love it, that might be simply because you don’t

know it as well, so when I’m asked what my favorite role is, usually

it’s the role I’m doing then because you get more excited and more

intimate with it this week because you’re doing it. However, when

deciding on roles, I think it’s better to know the weight of your

voice, then take off 15% and sing that repertoire. Too often

singers will go up 15% rather than opting to be conservative and stay

vocally healthy. Also, when you have control of your voice, you

have control of your interpretation. You can sing something the

way you feel it should be sung rather than being forced to sing it so

you’ll just manage to stay alive until the finale.

NR: There is a kind of logic to

your repertoire. One has to

look not at how high the role is, but what the weight of it is – the

tessitura and also the extremes. Some roles have lots of high D’s

or E-flats, and I couldn’t do that. Others don’t

have the high notes but sit lower and pull the voice down. There

are a number of things you take into consideration. I’m very

lucky now because people offer me everything from the ridiculous to the

sublime, so it’s up to me and to my advisors, my managers and agents

who are really colleagues. We really work these things out

together, but one decides on a role if you really love it.

However, if you don’t love it, that might be simply because you don’t

know it as well, so when I’m asked what my favorite role is, usually

it’s the role I’m doing then because you get more excited and more

intimate with it this week because you’re doing it. However, when

deciding on roles, I think it’s better to know the weight of your

voice, then take off 15% and sing that repertoire. Too often

singers will go up 15% rather than opting to be conservative and stay

vocally healthy. Also, when you have control of your voice, you

have control of your interpretation. You can sing something the

way you feel it should be sung rather than being forced to sing it so

you’ll just manage to stay alive until the finale. NR: To sing a French role in

Paris, yes. To singer Werther

there, definitely. It’s one of the great masterpieces, so it’s

like doing Bohème in

Milano. I was nervous that night,

which was good, but I wasn’t too nervous because I’d sung it in

Amsterdam and at the Met as well as in Sidney and one or two other

places. That one in Australia was a fabulous production by Elijah

Moshinsky with Carlo

Felice Cillario conducting. That was my

favorite, I think. The one in Paris was also wonderful. I

was lucky to have a production of that quality. It is hard to

describe, not a modern one nor a period production. It was set in

a timeless time in between. The public was taken aback when the

curtain went up. The stage was a diagonal row of flowers and

dirt, so the first aria about nature was sung to these roses, and as I

sang, the lights came up stronger and stronger so that at the end they

were like on fire. The more I sang and the more passionate the

music became, the more the flowers seemed to come to life. It was

very effective and the public liked it. The Paris public is very

quick to boo and scream and walk out, so it’s difficult to

please. Someone is booed usually every night, and it doesn’t have

to do with the reality of the evening. It’s just an odd

personality, that public.

NR: To sing a French role in

Paris, yes. To singer Werther

there, definitely. It’s one of the great masterpieces, so it’s

like doing Bohème in

Milano. I was nervous that night,

which was good, but I wasn’t too nervous because I’d sung it in

Amsterdam and at the Met as well as in Sidney and one or two other

places. That one in Australia was a fabulous production by Elijah

Moshinsky with Carlo

Felice Cillario conducting. That was my

favorite, I think. The one in Paris was also wonderful. I

was lucky to have a production of that quality. It is hard to

describe, not a modern one nor a period production. It was set in

a timeless time in between. The public was taken aback when the

curtain went up. The stage was a diagonal row of flowers and

dirt, so the first aria about nature was sung to these roses, and as I

sang, the lights came up stronger and stronger so that at the end they

were like on fire. The more I sang and the more passionate the

music became, the more the flowers seemed to come to life. It was

very effective and the public liked it. The Paris public is very

quick to boo and scream and walk out, so it’s difficult to

please. Someone is booed usually every night, and it doesn’t have

to do with the reality of the evening. It’s just an odd

personality, that public. NR: You have to be a little bit

screwy to kill yourself.

Lensky is younger than Werther and he kills himself – or allows himself

to be killed – but that can be attributed to the

impetuousness of

youth. Lensky cannot be played with great intellect. I play

him as a reasonable young man who gets wrapped up in

circumstance. Werther has a circumstance before we meet him in

the opera. The same with Don Carlos. Who is he?

There’s a lot to him that is put together before we see him. By

reading the Schiller you can get more depth of character. Whether

it is accurate or not, it’s better to have some understanding so you

can make him a whole person onstage.

NR: You have to be a little bit

screwy to kill yourself.

Lensky is younger than Werther and he kills himself – or allows himself

to be killed – but that can be attributed to the

impetuousness of

youth. Lensky cannot be played with great intellect. I play

him as a reasonable young man who gets wrapped up in

circumstance. Werther has a circumstance before we meet him in

the opera. The same with Don Carlos. Who is he?

There’s a lot to him that is put together before we see him. By

reading the Schiller you can get more depth of character. Whether

it is accurate or not, it’s better to have some understanding so you

can make him a whole person onstage.