A Conversation with Bruce Duffie

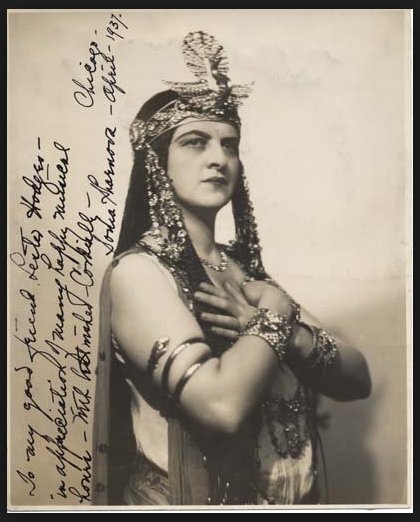

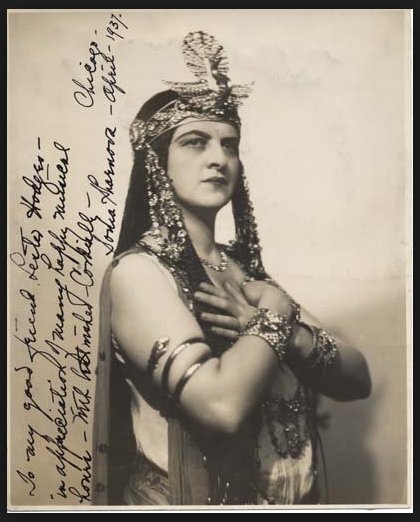

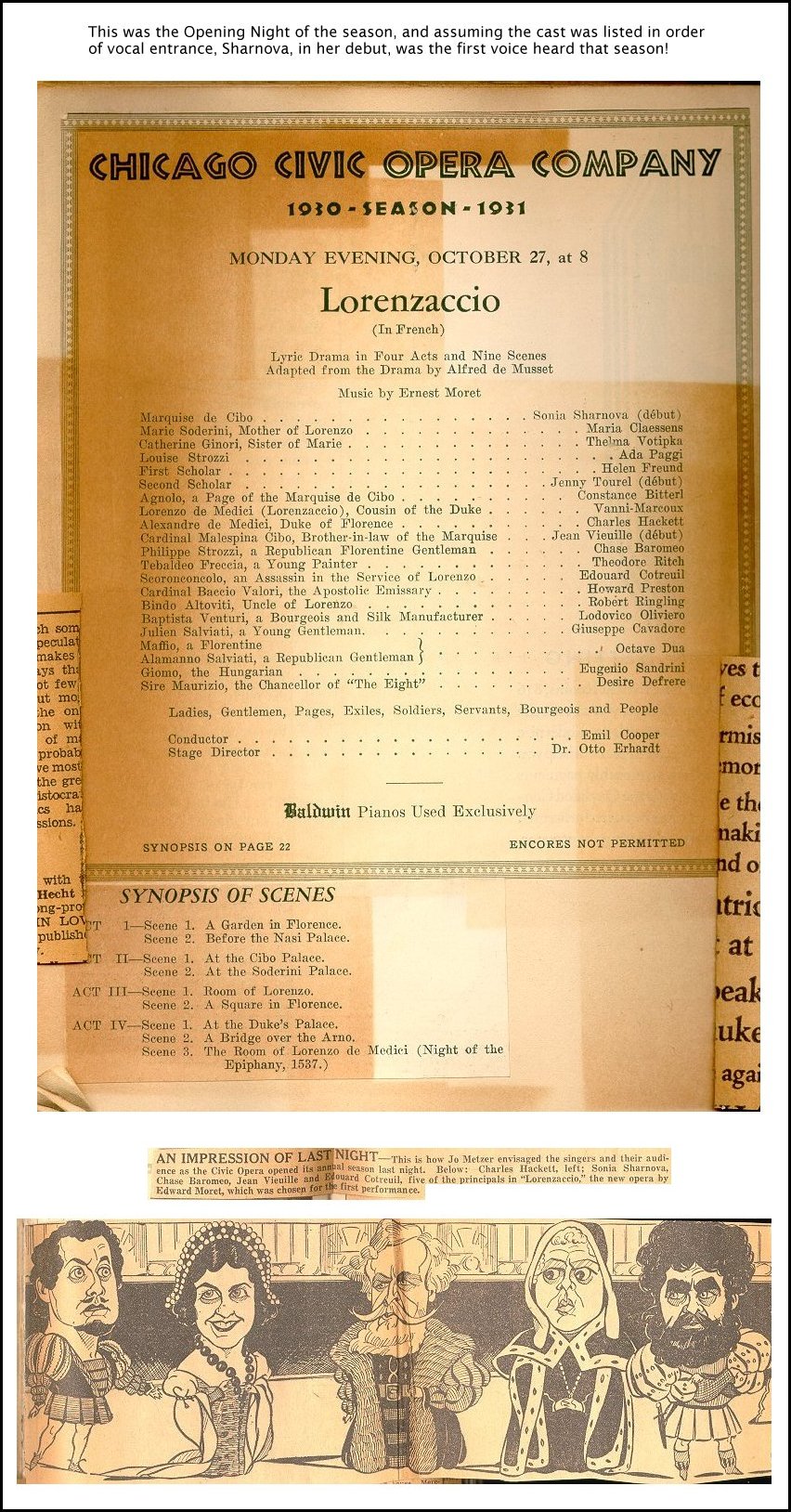

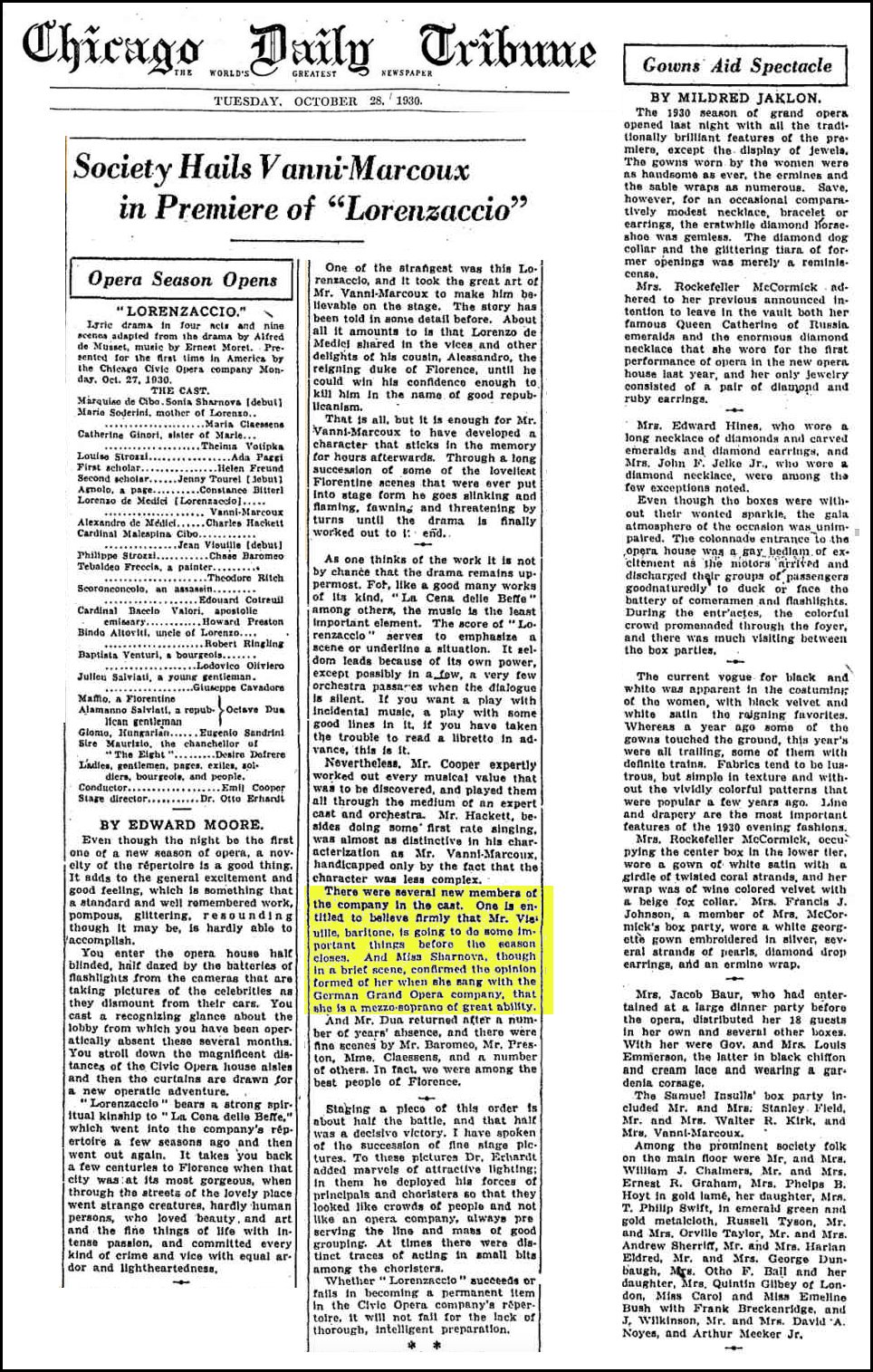

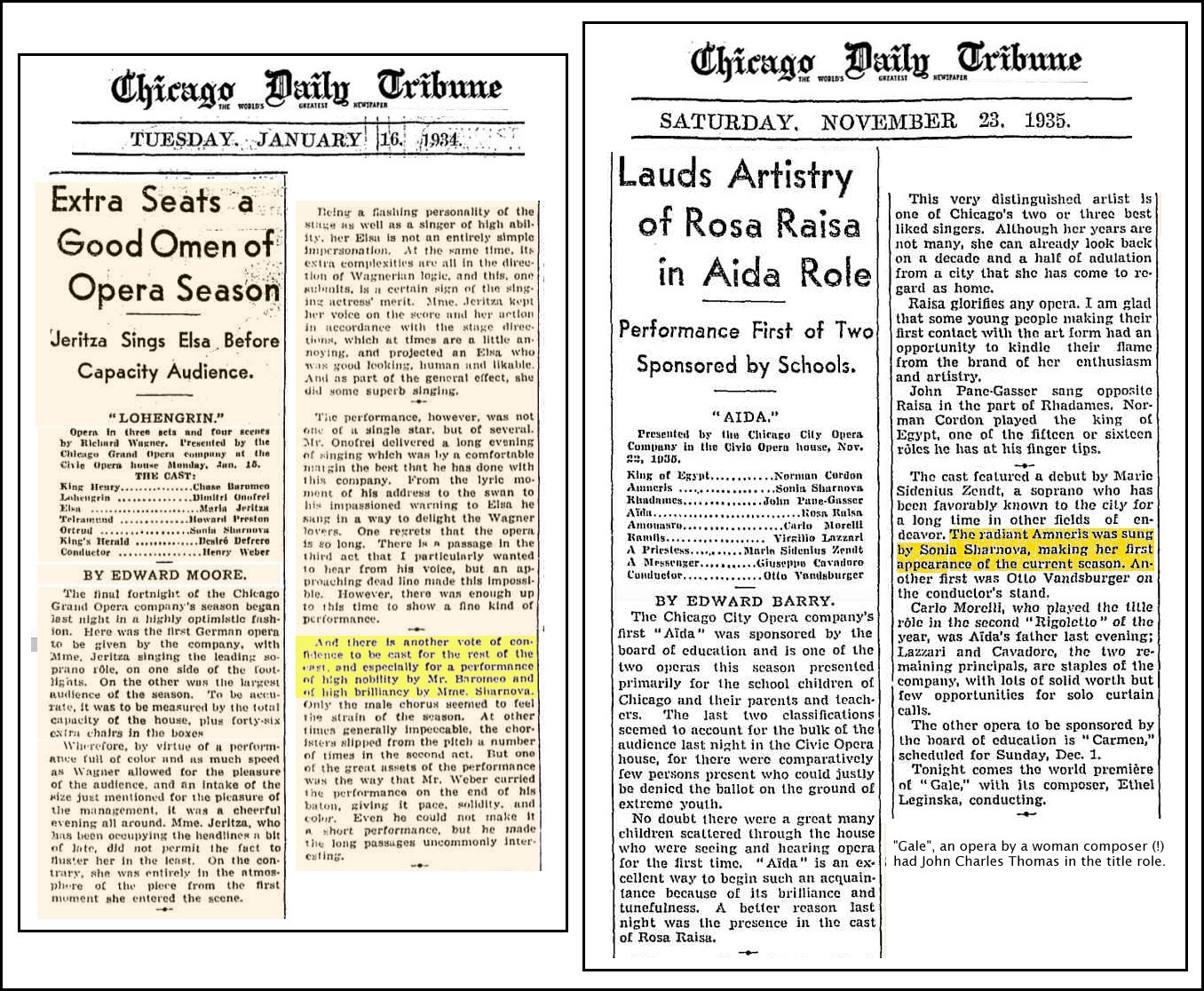

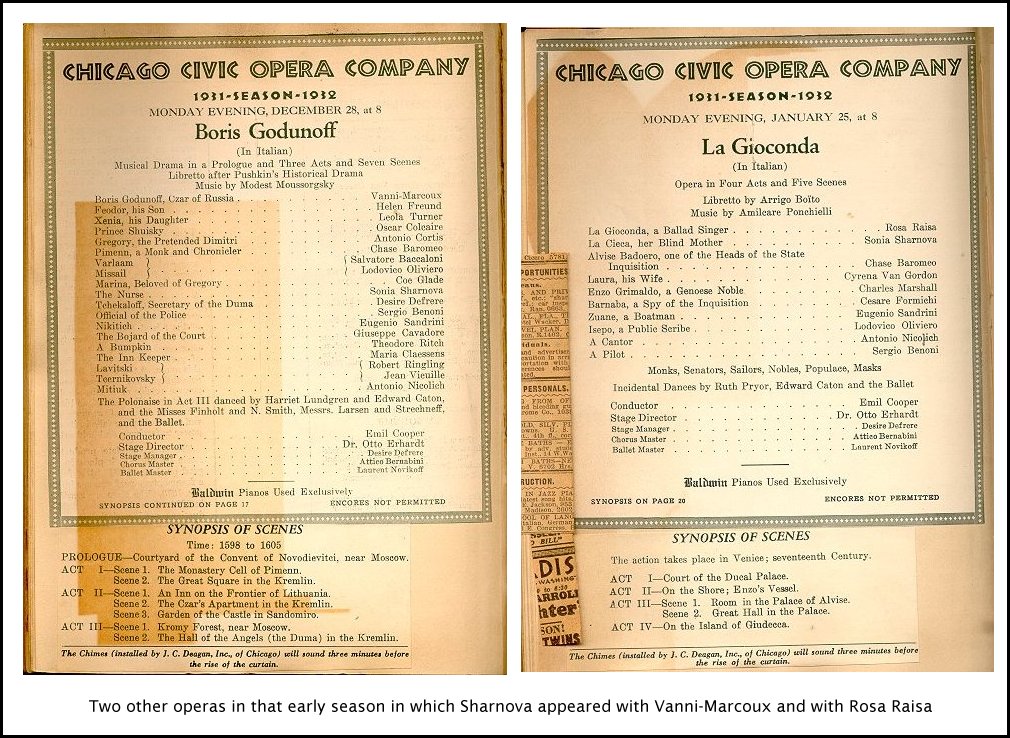

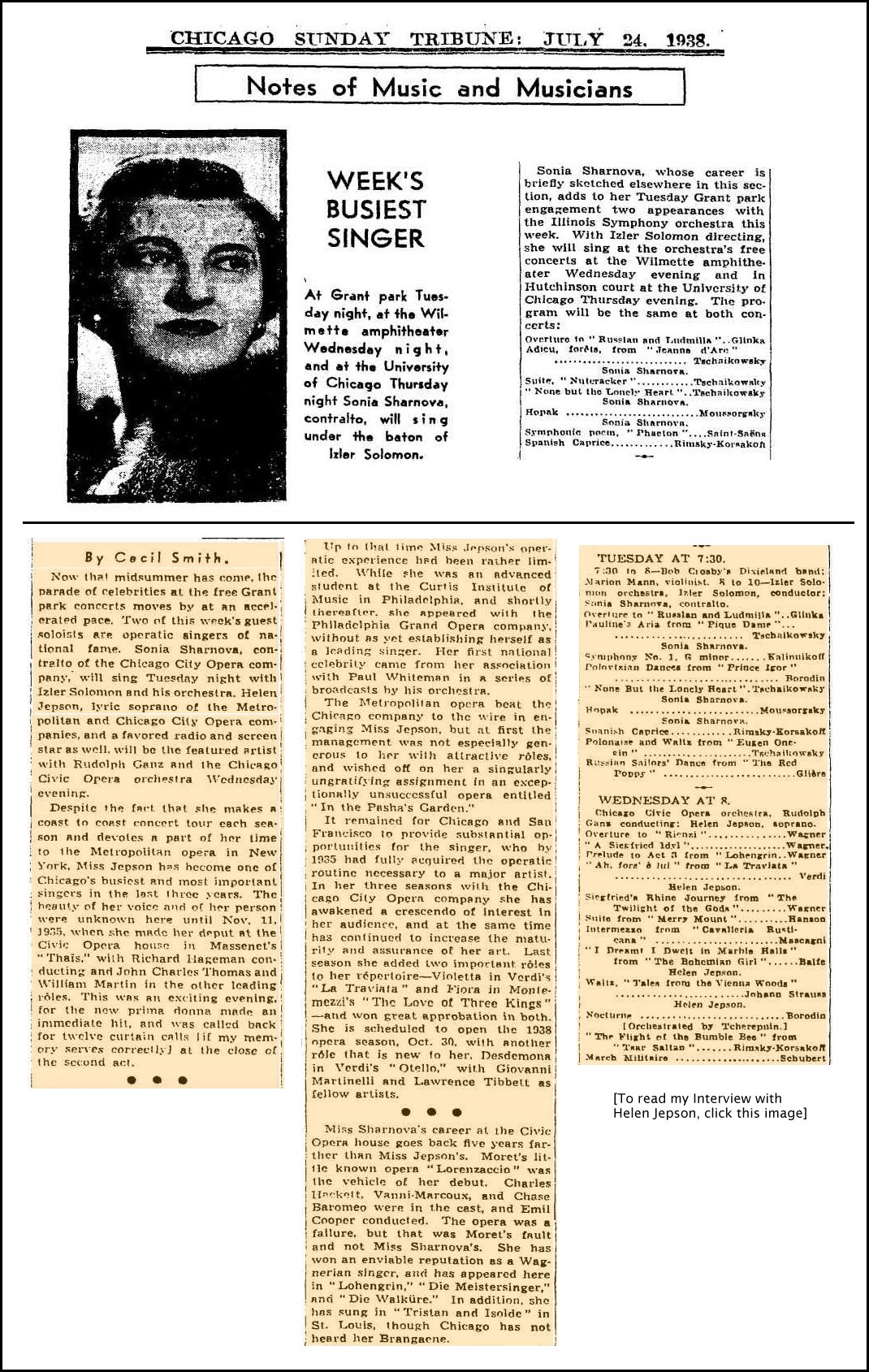

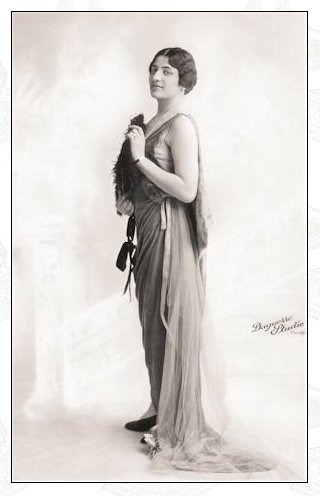

Sonia Sharnova, 92, Chicago Opera Diva

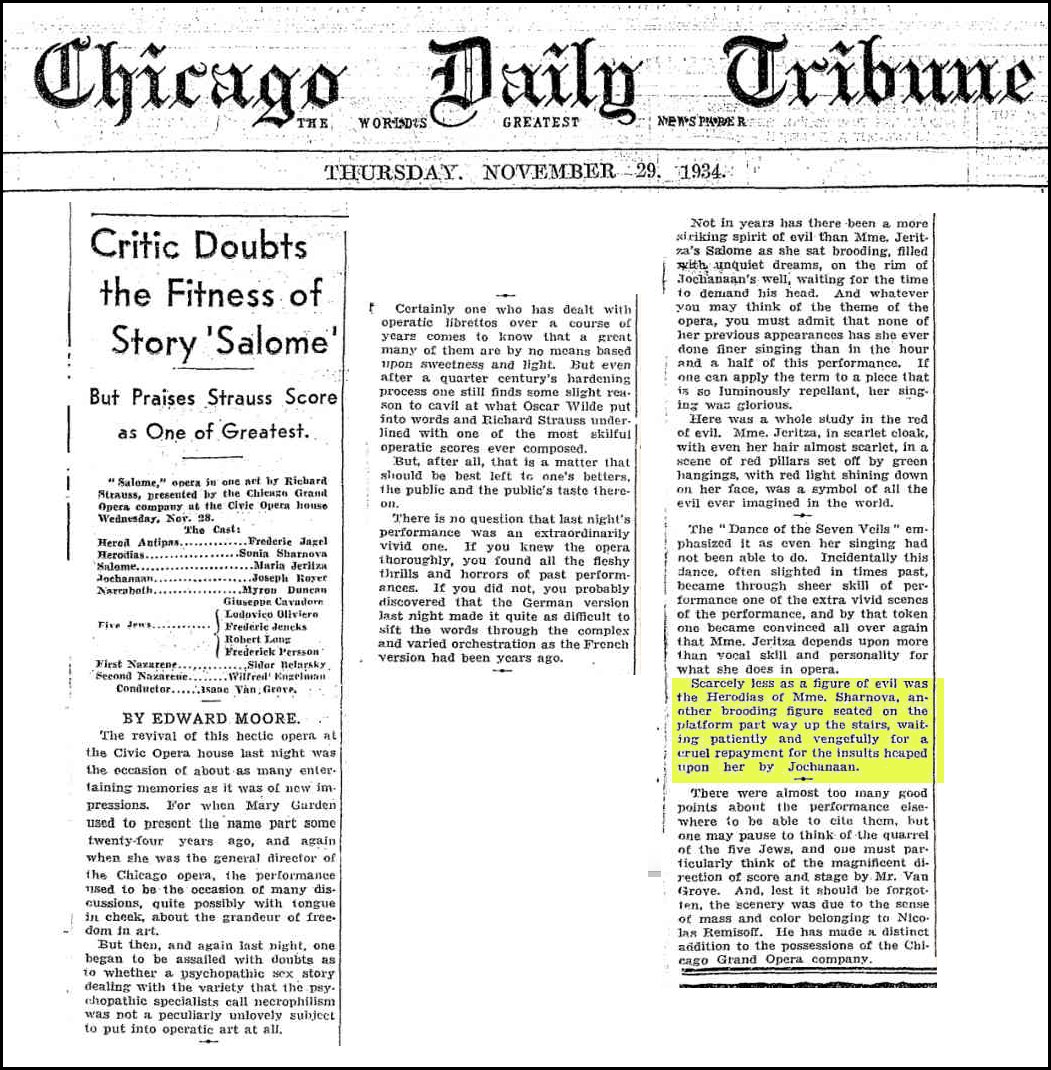

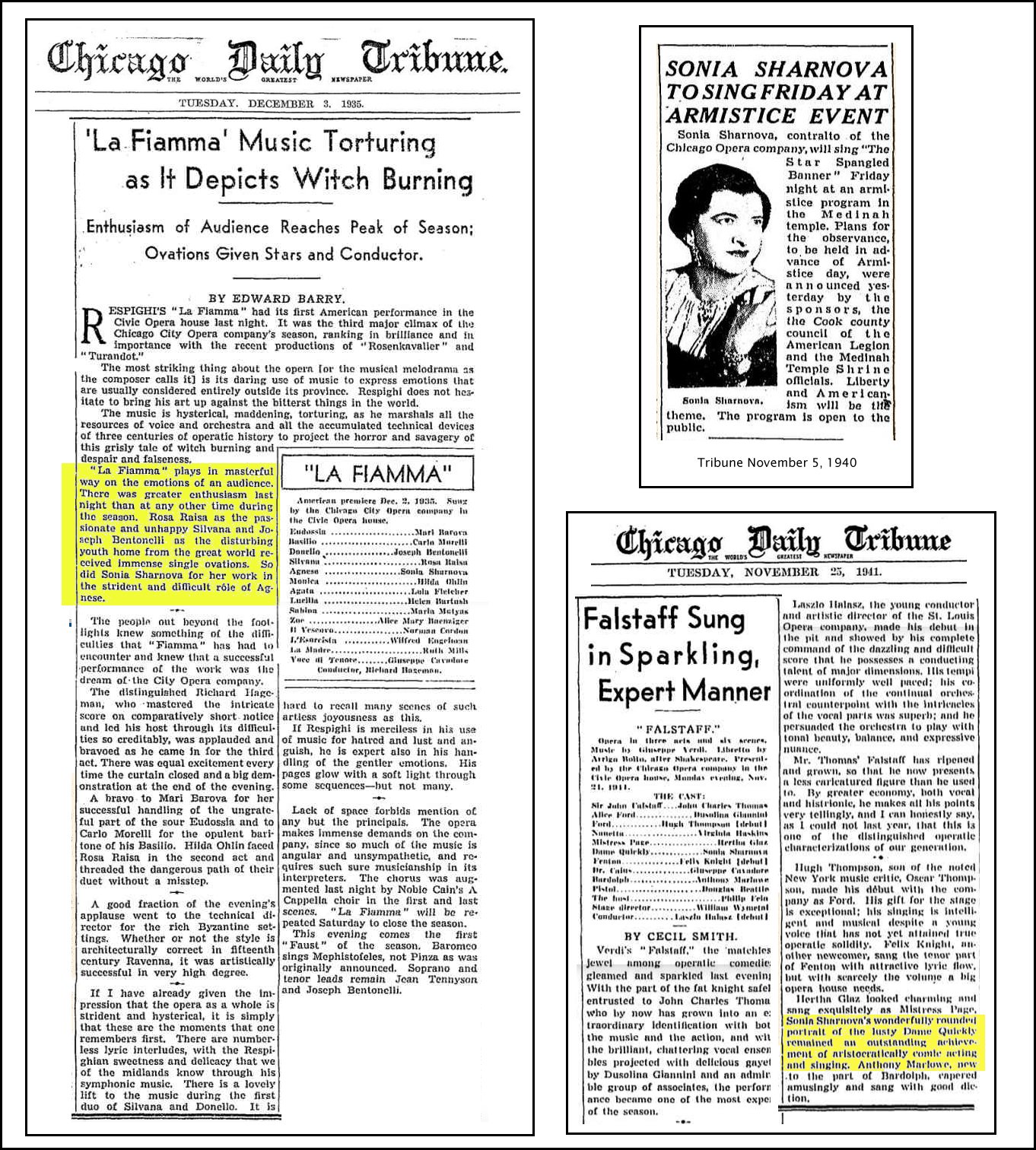

December 5, 1988 Chicago Tribune (Obituary)

[Text only - photo from another source]

Sonia Sharnova, 92, a contralto of the former Chicago

Civic Opera, was considered one of the best opera singers in Chicago

and until recently gave vocal lessons to boys. Sonia Sharnova, 92, a contralto of the former Chicago

Civic Opera, was considered one of the best opera singers in Chicago

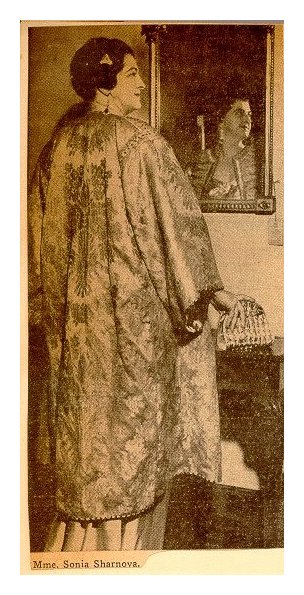

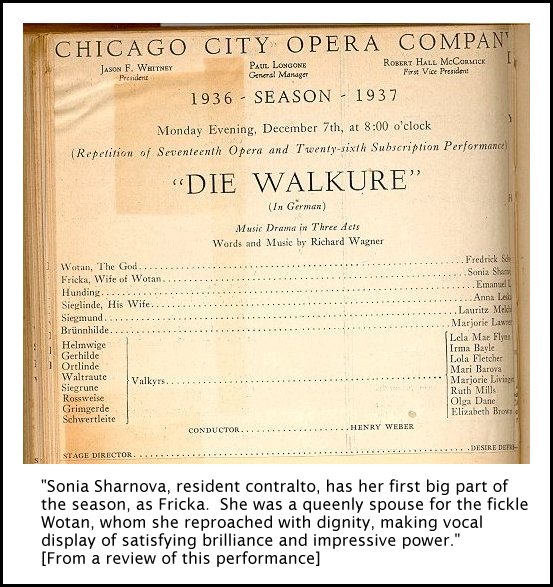

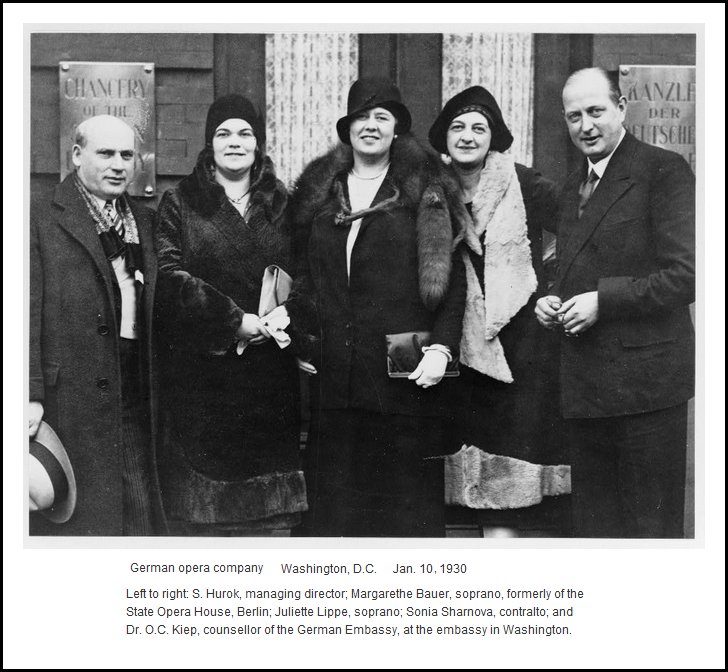

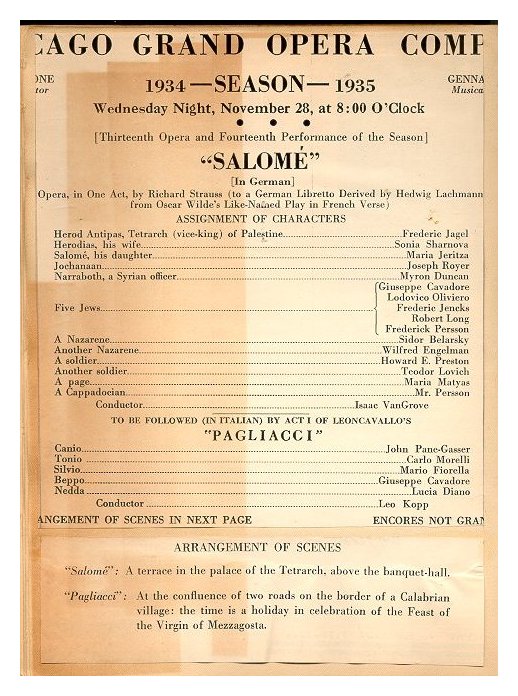

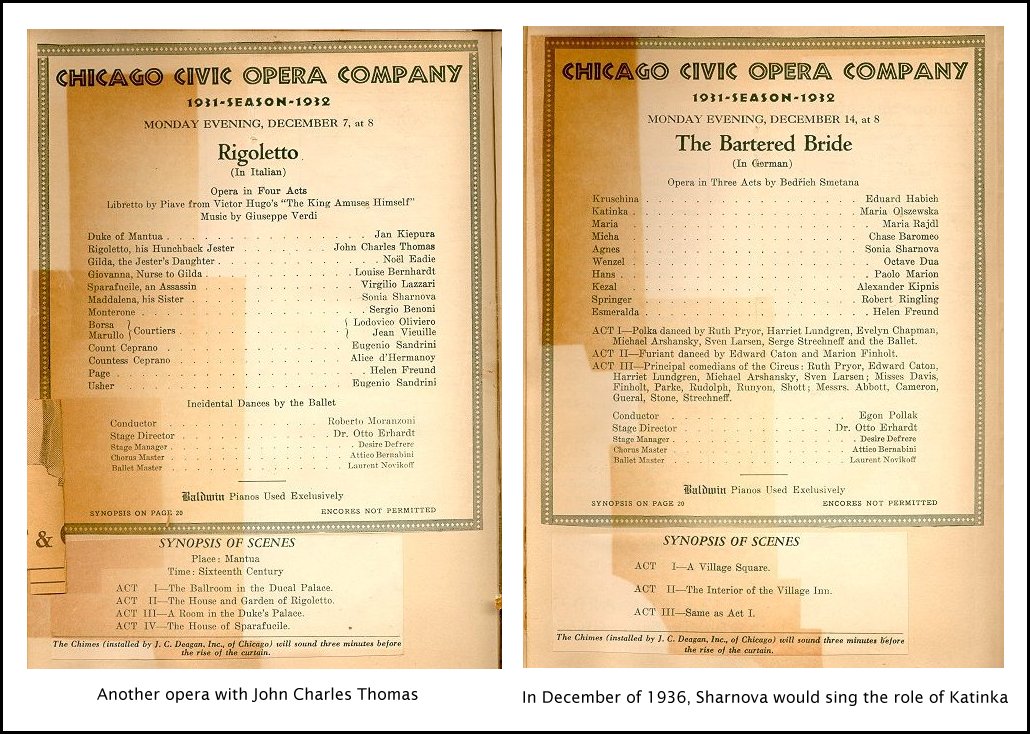

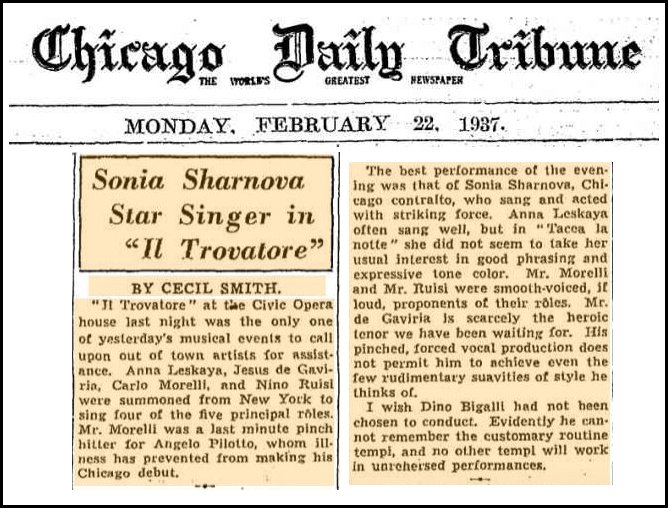

and until recently gave vocal lessons to boys.Services for Miss Sharnova, a Near North Side resident, will be held at 10 a.m. Tuesday in the chapel at 5206 N. Broadway. She died Saturday in Michael Reese Hospital and Medical Center. Miss Sharnova made her first appearance in Wagnerian opera in 1929 with the German Grand Opera company. The next year she appeared with the Chicago Civic opera. In 1932 she was a member of the Chicago Stadium Grand opera. She was known for her work as a leading contralto of the German National Opera Company, the Chicago Opera Companies, German repertory and her voice teaching. Notable among her numerous roles was Fricka in Die Walküre and Herodias in Salome. Her last major public appearance was in 1954 in a performance of` Faust during the Ravinia Festival in Highland Park, the summer home of the Chicago Symphony. Her 90th birthday, May 2, 1986, was designated “Sonia Sharnova Day” in Chicago by Mayor Harold Washington. “She was almost 6 feet tall and stood just as erect as a soldier. She had tremendous energy and an incredibly fine mind and always strove for excellence,” said Arthur Segil, her nephew. Miss Sharnova coached voice in Chicago for numerous years. She was honored by the Chicago Cultural Center, Chicago Historical Society and the Cliff Dwellers cultural group. She was a past president of the Womens Club of Musicians and the National Association of Teachers of Singing. Miss Sharnova, the widow of I.T. Feingold, is survived by a daughter, Thelma Feldman; a son, Gene Feingold; a sister; two grandchildren and three great-grandchildren. |

Here

is much of what Sharnova said during our encounter . . . . . . . . .

Here

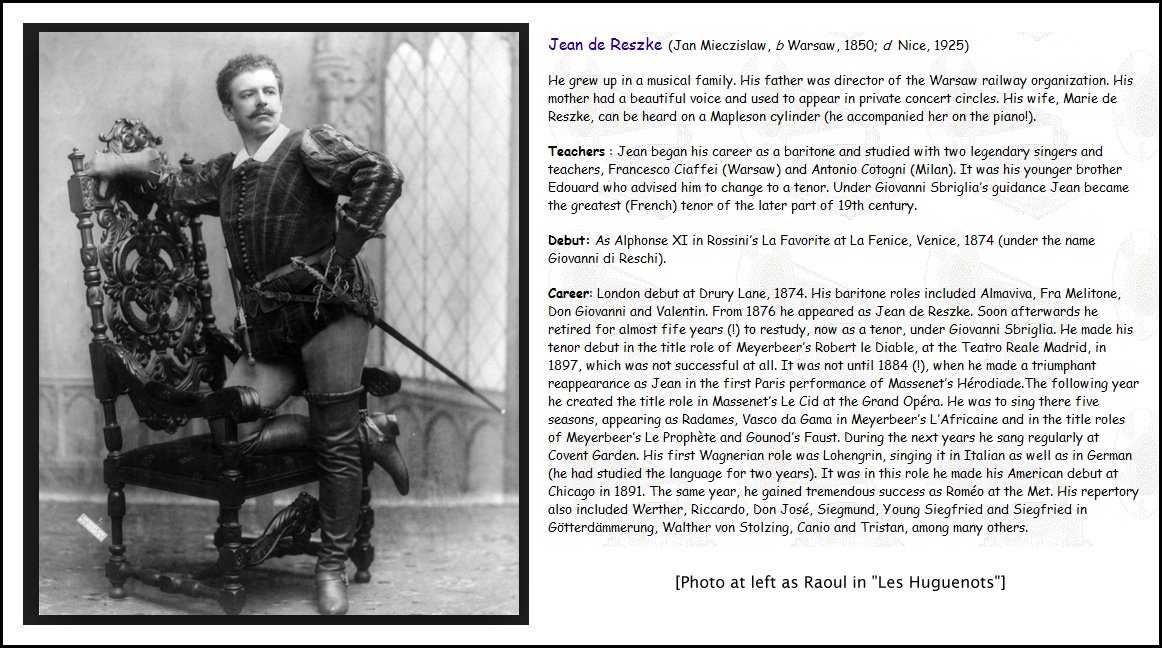

is much of what Sharnova said during our encounter . . . . . . . . . SS: Yes, I think

so. He made a stage out of his living room and had it set for the

last act of Aïda.

When he felt in good voice, he sang with us. I’ll never forget

that and it was really wonderful. He was very sure I was going to

be a great success. He was giving a performance of Don Giovanni and wanted me for a

chorister, and I regret to this day that I did not do it. I had

already sung professionally and didn’t want to be in a chorus, but that

was small-minded of me. He was going to stage the work and all

his pupils were going to be it in. He worked very hard on the

production, and only a few weeks after that, he died. That was

early April of 1925.

SS: Yes, I think

so. He made a stage out of his living room and had it set for the

last act of Aïda.

When he felt in good voice, he sang with us. I’ll never forget

that and it was really wonderful. He was very sure I was going to

be a great success. He was giving a performance of Don Giovanni and wanted me for a

chorister, and I regret to this day that I did not do it. I had

already sung professionally and didn’t want to be in a chorus, but that

was small-minded of me. He was going to stage the work and all

his pupils were going to be it in. He worked very hard on the

production, and only a few weeks after that, he died. That was

early April of 1925.

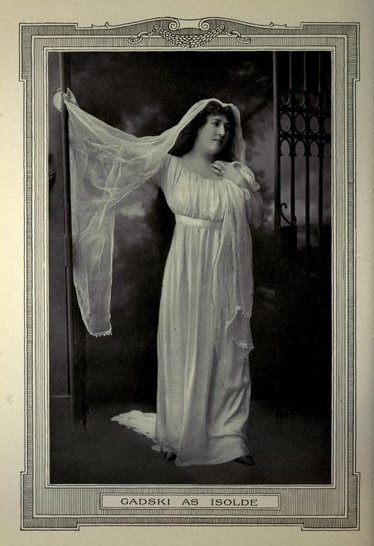

Johanna

Gadski was born in Anklam, Prussia in 1872, and studied singing with

Mme. Schröder-Chaloupha in Stettin. In 1889, at the age of 17, she

made

her debut at the Kroll Theatre in Berlin as Agathe in Der Freischütz.

She gained valuable experience singing in provincial German opera

houses, returning to the Kroll in 1892. In 1895 she began to expand her

career internationally, touring Holland and the United States. She sang

with the Damrosch Opera Company in 1895-96, creating the role of Hester

Prynne in Walter Damrosch's opera, The

Scarlet Letter. Further appearances with Damrosch took place in

1898-99. She made her debut at Covent Garden in 1899 as Elizabeth in Tannhäuser, and later that

year sang Eva in Die Meistersinger

at Bayreuth. Johanna

Gadski was born in Anklam, Prussia in 1872, and studied singing with

Mme. Schröder-Chaloupha in Stettin. In 1889, at the age of 17, she

made

her debut at the Kroll Theatre in Berlin as Agathe in Der Freischütz.

She gained valuable experience singing in provincial German opera

houses, returning to the Kroll in 1892. In 1895 she began to expand her

career internationally, touring Holland and the United States. She sang

with the Damrosch Opera Company in 1895-96, creating the role of Hester

Prynne in Walter Damrosch's opera, The

Scarlet Letter. Further appearances with Damrosch took place in

1898-99. She made her debut at Covent Garden in 1899 as Elizabeth in Tannhäuser, and later that

year sang Eva in Die Meistersinger

at Bayreuth.The 27 year-old Johanna Gadski made her Metropolitan Opera debut in a Philadelphia performance of Tannhäuser, on 28 December 1899, substituting for Milka Ternina as Elizabeth. Within two weeks, Gadski made her official Met debut in New York on 6 January 1900 as Senta in Der Fliegende Holländer, soon adding the roles of Sieglinde and Eva. During the next two years at the Met, Gadski added roles from the Italian repertory singing Aïda, Donna Elvira (Don Giovanni), Santuzza (Cavalleria Rusticana), Valentine (Les Huguenots) and Amelia (Ballo in Maschera) demonstrating versatility equaling that of Nordica and Eames. In 1904 Gadski left the Met for two seasons, giving extensive concert tours in the United States during 1905 and 1906. It was during this period that she studied the role of Isolde with Lilli Lehmann. She performed at the Salzburg Festival as Donna Elvira in 1906 (and later in 1910) with Lilli Lehmann as Donna Anna. She also sang Pamina in 1910, Lehmann performing as the First Lady. Upon her return to the Metropolitan Opera, she sang her first Isolde on 15 February 1907. In addition to the standard repertoire, Gadski sang in premieres of Dame Ethel Smyth's Der Wald in 1903 (the first opera by a woman to be performed at the Met), Ludwig's Thuille's Lobetanz in 1911 and Leo Blech's Versiegelt in 1912. Gadski's career at the Met lasted until 1917. From 13 April 1917, the date of Gadski's last performance at the Met (as Isolde) to 28 November 1921, no performances there were sung in German. The few Wagnerian operas performed, beginning in 1920, were sung in English. Johanna Gadski returned to the United States in 1926, under the auspices of Sol Hurok, for a series of Wagnerian concerts. Her success led Hurok to organize a German Opera Company to support Gadski in performances of Wagner's Ring cycle. They toured ten cities, including Philadelphia and Chicago. In 1928, Hurok once again formed a company starring Gadski, and expanded the repertory. The tours took place from 1928 to 1930. Gadski formed her own company and appeared in 1930-31. She planned to return to the United States for yet another tour in 1932, but died early that year in an automobile accident. -- Harold Bruder (From

liner notes to a CD re-issue on the Marston label)

|

BD:

Tell me about some of the other highlights of your fascinating

career.

BD:

Tell me about some of the other highlights of your fascinating

career.

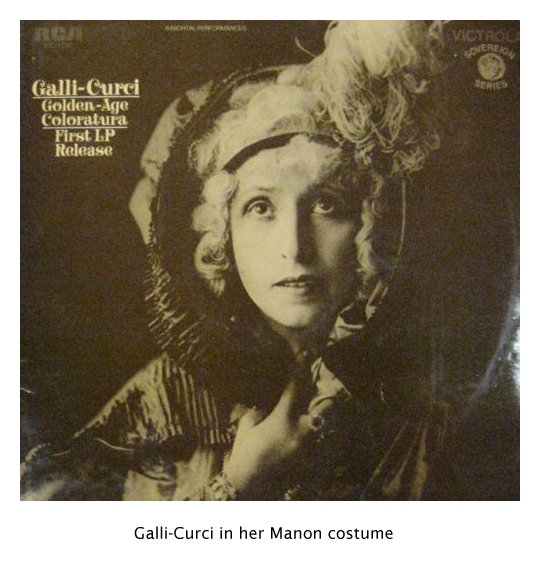

Amelita

Galli-Curci

(18 November 1882 – 26 November 1963) was an Italian coloratura

soprano. She was one of the best-known operatic singers of the early

20th century with her gramophone records selling in large numbers. She

was born as Amelita Galli into an upper-middle-class family in Milan,

where she studied piano at the Milan Conservatory, winning a gold medal

and at the age of 16 was offered a position as a "professor" or teacher

there. She was inspired to sing by her grandmother. Operatic composer

Pietro Mascagni also encouraged Galli-Curci's singing ambitions. By her

own choice, Galli-Curci's voice was largely self-trained. She honed her

technique by listening to other sopranos, reading old singing-method

books, and doing piano exercises with her voice instead of using a

keyboard. She

was born as Amelita Galli into an upper-middle-class family in Milan,

where she studied piano at the Milan Conservatory, winning a gold medal

and at the age of 16 was offered a position as a "professor" or teacher

there. She was inspired to sing by her grandmother. Operatic composer

Pietro Mascagni also encouraged Galli-Curci's singing ambitions. By her

own choice, Galli-Curci's voice was largely self-trained. She honed her

technique by listening to other sopranos, reading old singing-method

books, and doing piano exercises with her voice instead of using a

keyboard.Galli-Curci made her operatic debut in 1906 at Trani, as Gilda in Giuseppe Verdi's Rigoletto, and she rapidly became acclaimed throughout Italy for the sweetness and agility of her voice and her captivating musical interpretations. She was seen by many critics as an antidote to the host of squally, verismo-oriented sopranos then populating Italian opera houses. The soprano had toured widely in Europe (including appearances in Russia in 1914) and South America. In 1915, she sang two performances of Lucia di Lammermoor with Enrico Caruso in Buenos Aires. These were to be her only appearances in opera with the great tenor, though they later appeared in concert and made a few recordings together. Galli-Curci and Caruso also acted as godparents for the son of the Sicilian tenor Giulio Crimi. Galli-Curci arrived in the United States in 1916 as a virtual unknown. Her stay was intended to be brief, but the acclaim she received for her performance as Gilda in Rigoletto in Chicago on November 18, 1916 (her 34th birthday) was so wildly enthusiastic that she accepted an offer to remain with the Chicago Opera Company. She was a member of the company until the end of the 1924 season. Also in 1916, Galli-Curci signed a recording contract with the Victor Talking Machine Company and recorded exclusively for the company until 1930. While still under contract with the Chicago Opera, Galli-Curci joined the Metropolitan Opera in 1921. She remained with the Met until her retirement from the operatic stage nine years later. She also sang in Great Britain, appearing in 20 cities during a 1924 tour, and visited Australia a year later for a series of recitals. Galli-Curci built and maintained an estate called Sul Monte in Highmount, New York, where she summered for many years until she sold the estate in 1937. In the nearby village of Margaretville a theater was erected and named in her honor. She returned the favor by performing there on its opening night. Sul Monte was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 2010. Weary of opera house politics and convinced that opera was a dying art form, Galli-Curci retired from the operatic stage in January 1930 to concentrate instead on concert performances. Throat problems and the uncertain pitching of top notes had plagued her for several years and she underwent surgery in 1935 for the removal of a thyroid goiter. Great care was taken during her surgery, which was performed under local anesthesia; however, her voice suffered following the surgery. A nerve to her larynx, the external branch of the superior laryngeal nerve, is thought to have been damaged, resulting in the loss of her ability to sing high pitches. This nerve has since become known as the "nerve of Galli-Curci." Researchers Crookes and Recaberen "examined contemporary press reviews after surgery, conducted interviews with colleagues and relatives of the surgeon, and compared the career of Galli-Curci with that of other singers" and found, in 2001, that her vocal decline was most likely not caused by a surgical injury. In 1908 Galli-Curci wed a nobleman, the Marchese Luigi Curci, attaching his surname to hers. They divorced in 1920. The following year, she married Homer Samuels, her accompanist. The Marchese Curci petitioned the papal council in Rome for an annulment of the marriage in 1922. Galli-Curci was a student of the Indian meditation and yoga teacher Paramahansa Yogananda. She wrote the foreword to Yogananda's 1929 book Whispers from Eternity.  |

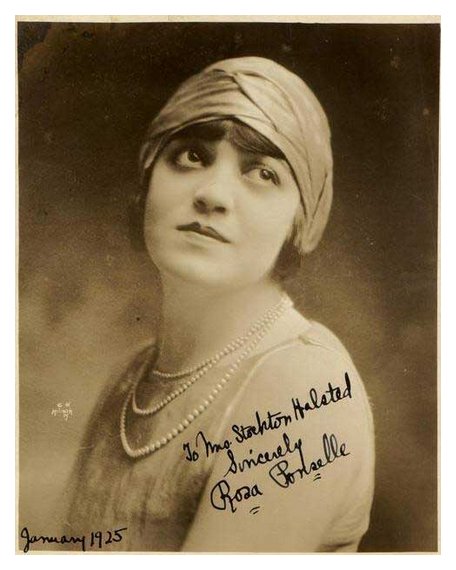

Anytime

is a good time to remember Rosa Ponselle, even if you never heard her

in person or listened to one of her extraordinary recordings. For it

was she who unwittingly championed the American born and trained

singer. Of course, there had been Americans on the roster of the

Metropolitan Opera from its first season in 1883, but before Ponselle

there had been no leading singer who had not first made his or her mark

abroad. In contrast, the Met was the first operatic stage on which she

appeared, and her performances outside the United States were few. Anytime

is a good time to remember Rosa Ponselle, even if you never heard her

in person or listened to one of her extraordinary recordings. For it

was she who unwittingly championed the American born and trained

singer. Of course, there had been Americans on the roster of the

Metropolitan Opera from its first season in 1883, but before Ponselle

there had been no leading singer who had not first made his or her mark

abroad. In contrast, the Met was the first operatic stage on which she

appeared, and her performances outside the United States were few.Caruso found her—she was then Rosa Ponzillo—and his friend Giulio Gatti-Casazza, former general manager of the Met, gambled on her. “If she succeeds,” Gatti told Caruso, “American singers will have the doors opened to them. If she fails, I will be on the first boat back to Italy, and New York will never see my face again.” Gatti was not being melodramatic. The step was a big one, as it involved an operatically inexperienced, twenty-one-year-old soprano. But her talent was so big. When Gatti made the decision to engage her—at $150 per week—it was to his credit that he presented Ponselle not in a small role or buried her debut deep in the season. She first appeared at the Met in the opening week of the 1918–19 season as Leonora in La forza del destino opposite Caruso and Giuseppe De Luca. This was the Met premiere of the opera. “The newcomer is American,” began James Gibbons Huneker’s review in The New York Times the following morning. “She is young, she is comely, and she is tall and solidly built. Added to her personal attractiveness, she possesses a voice of natural beauty that may prove a gold mine. It is vocal gold, anyhow, with its luscious lower and middle tones, dark rich, ductile, brilliant and flexible in the upper register.” Rosa began at the top and twenty years later she left at the top. In the decades between, the lot of the American singer improved dramatically as Gatti had hoped it would. -- John Ardoin (From

liner notes to a CD re-issue on the Marston label)

|

|

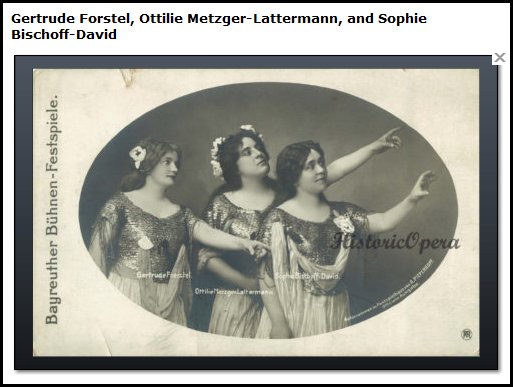

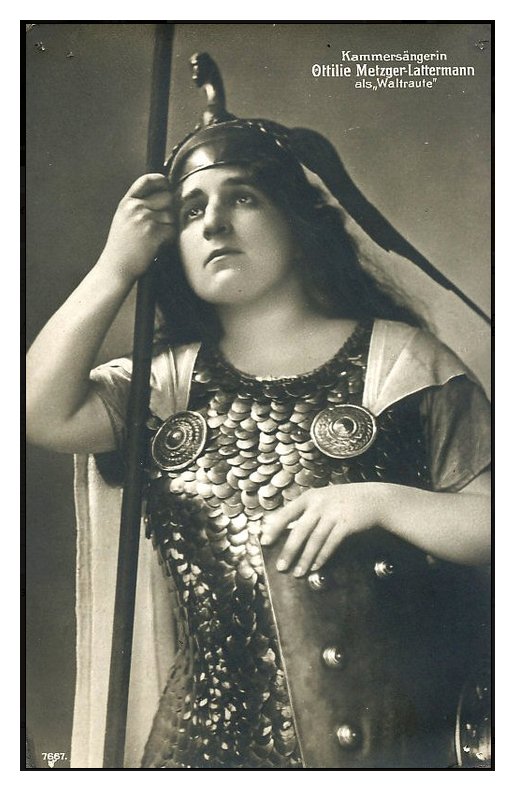

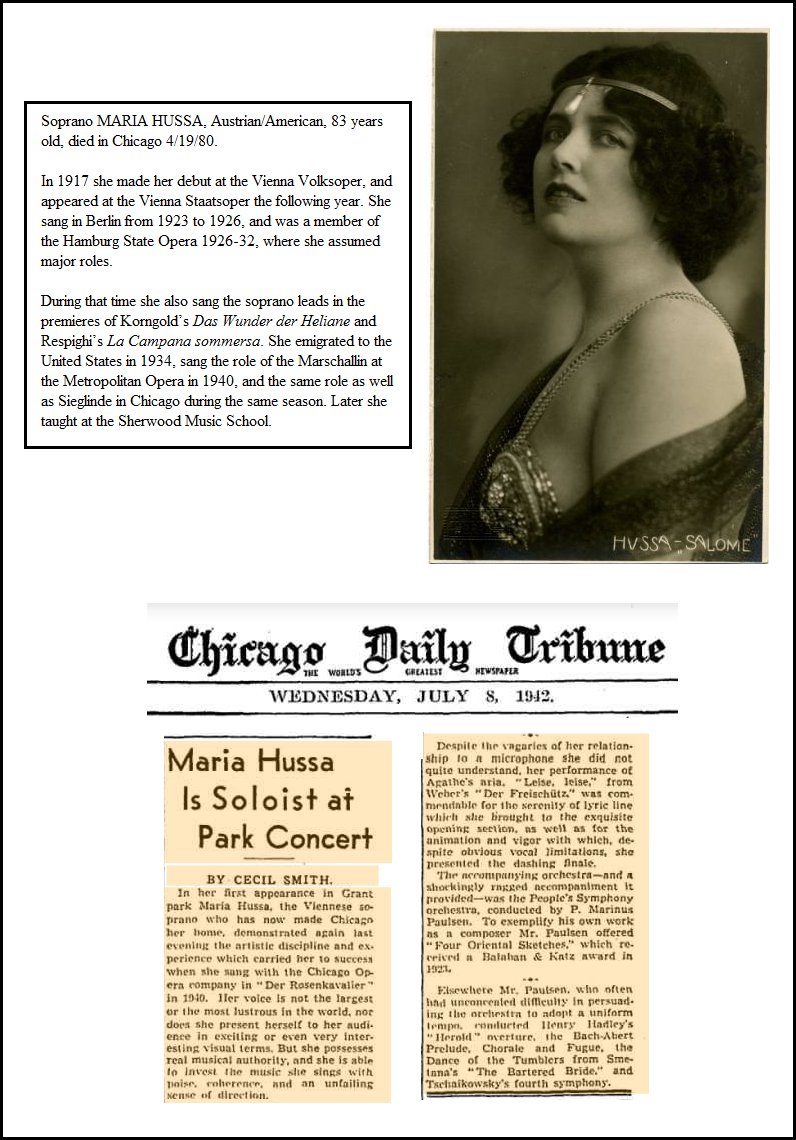

Ottilie Metzger-Lattermann

also formerly Ottilie Metzger-Froitzheim (15 July 1878 – February 1943)

was a German contralto who was a famous performer of works by Wagner

during the 1910s, and who after her retirement was murdered in

Auschwitz.

Matzger was born in Frankfurt. Her first husband was the author Clemens Froitzheim. In Hamburg she met the bass-baritone Theodor Lattermann who became her second husband. From 1901 until 1912, she sang at Bayreuth Festival, where her Erda in Der Ring des Nibelungen was esteemed.  She was a student of Selma Nicklass-Kempner, Georg Vogel and Emanuel Reicher (acting). Her debut was 1898 in Halle, followed by engagements in Cologne, then from 1903 to 1915 first contralto with the Hamburg State Opera and played opposite Enrico Caruso. Then followed Dresden, Bayreuth Festival, Vienna State Opera, Saint Petersburg, Prague, Zurich Opera, Amsterdam, Munich, Budapest, Royal Opera House Covent Garden and tours with conductor Leo Blech in the USA. This ended in 1925 with the illness of Theodor who died on 4 March 1926 aged 46. From 1927 she taught singing at the Stern Conservatory in Berlin, where she herself had studied.  Metzger-Lattermann continued to perform as a Lieder recitalist, often accompanied by Richard Strauss and Hans Pfitzner. She gave her last concerts in 1933 under Bruno Walter in Berlin and Otto Klemperer in Dresden, with the seizure of power by Hitler. After 1933, under the Nazi regime, Metzger-Lattermann continued to perform for Jewish audiences, on at least one occasion in a Lieder evening with the baritone Erhard Wechselmann, who was also to perish in Auschwitz.  In 1933, the American theatre impresario George

Blumental (a former associate of Oscar Hammerstein I, who in 1917 had

tried to set up theatres for American troops in Paris), tried to

arrange with Georg Hartmann and Arthur Hirsch to bring over conductor

Blech and a troupe of 12 Jewish opera singers to present Wagner's Ring

in New York. Hirsch's assistant, Otto Metzger, was Ottilie's brother

and Ottilie was on the list. Blumental's plans came to nothing, partly

due to the unavailability of Blech, Klemperer, and Walter. In 1933, the American theatre impresario George

Blumental (a former associate of Oscar Hammerstein I, who in 1917 had

tried to set up theatres for American troops in Paris), tried to

arrange with Georg Hartmann and Arthur Hirsch to bring over conductor

Blech and a troupe of 12 Jewish opera singers to present Wagner's Ring

in New York. Hirsch's assistant, Otto Metzger, was Ottilie's brother

and Ottilie was on the list. Blumental's plans came to nothing, partly

due to the unavailability of Blech, Klemperer, and Walter.Metzger-Lattermann and her daughter fled to Brussels in 1939, but there were later rounded up by the Nazis and sent to the camps. She died in Auschwitz. The exact circumstances of the deaths of herself and her daughter are unknown. *

* *

* *

* * *

Perhaps the single greatest contralto of the 20th Century was a Jewish-German singer by the name of Ottilie Metzger-Lattermann. (1878-1943) Basically unknown today except by the most knowledgeable record collectors, her singing will still will bring a standing ovation by the cognoscenti. I witnessed one when giving a lecture to the Vocal Record Society several years ago and playing the Brahm's lied "Sapphische Ode". Metzger-Lattermann played Carmen to Caruso's Don Jose in Hamburg, was the 1st Alto in the World Premier of Mahler's 8th Symphony in Munich and even created a part for Siegfried Wagner in his opera Bruder Lustig. She sang internationally to great acclain, from Berlin to Vienna, St. Petersburg to Brussels, Covent Garden to the United States, even Bayreuth from 1901-1912. She was forced to run for her life in 1939, landed in Brussels where the Nazi's took her and put her on a train bound for Auschwitz. The records of her existence end in February, 1943. Kaiser Wilhelm II who was living in Holland at the time tried to intercede on her behalf, but to no avail. After the death of Winnifred Wagner, the Wagner family with some outside cajoling erected a monument to two of their greatest Jewish singers who perished in the Holocaust, one was soprano Henriette Gottlieb, the other Ottilie Metzger-Lattermann. -- From the Music

Antiquarian Blog, 3/27/12

|

Born: August 12, 1892 - Ludwigsschwaige, Augsburg, Bavaria, Germany Died: May 17, 1969 - Klagenfurt, Germany The German contralto, Maria Olszewska, studied with Karl Erler in Munich and began her career as a concert singer. Subsequently, she was heard by conductor Artur Nikisch who felt that her voice was of operatic calibre and should be presented on stage. Through his recommendation, Maria Olszewska made her debut in Krefeld in a 1917 production of Tannhäuser singing the role of a page. By 1920, she had advanced to Leipzig where her roles encompassed the larger Wagnerian mezzo parts, such as Brangäne, Fricka, and Waltraute. In Hamburg, she participated in the premiere of Erich Korngold's Die Tote Stadt, presented jointly with Cologne. The Vienna Opera engaged her in 1925 and she began to ingratiate herself with the demanding public there. Making her Covent Garden debut in 1924, Maria Olszewska offered a Herodias described as "outstanding" as were her Waltraute, Brangäne, and Fricka. In May 1925, her collaboration with Lotte Lehmann in Lohengrin caused Ernest Newman to write that the pair "showed us what a masterpiece the second act of the opera really is." She remained at Covent Garden through 1933. Maria Olszewska sang with the Chicago Opera from 1928 to 1932. There, she opened the company's last season at the venerable Auditorium with her Carmen and sang Fricka with a cast that included Frida Leider's Brünnhilde, Eva Turner's Sieglinde, and Alexander Kipnis' bass-voiced Wotan. Other roles she essayed in Chicago included Octavian, Brangäne, Ortrud, Magdalene, Katinka (in Smetana's Bartered Bride), the Third Lady, and the title role in Massenet's Hérodiade.  |

Charlotte "Lotte" Lehmann

(February 27, 1888 – August 26, 1976) was a German soprano who was

especially associated with German repertory. She gave memorable

performances in the operas of Richard Strauss, Richard Wagner, Ludwig

van Beethoven, Puccini, Mozart, and Massenet. The Marschallin in Der

Rosenkavalier, Sieglinde in Die Walküre and the title-role in

Fidelio are considered her greatest roles. During her long career,

Lehmann also made more than five hundred recordings. Her performances

in the world of Lieder are considered among the best ever recorded. After studying in Berlin with Mathilde Mallinger, she

made her debut at the Hamburg Opera in 1910 as a page in Wagner's

Lohengrin. In 1914, she gave her debut as Eva in Die Meistersinger von

Nürnberg at the Vienna Court Opera – the later Vienna State Opera

–, which she joined in 1916. She quickly established herself as one of

the company's brightest, most beloved stars in roles such as Elisabeth

in Tannhäuser and Elsa in Lohengrin. She created roles in the

world premieres of a number of operas by Richard Strauss, including the

Composer in Ariadne auf Naxos in 1916 (later she sang the title-role in

this opera), the Dyer's Wife in Die Frau ohne Schatten in 1919 and

Christine in Intermezzo in 1924. Her other Strauss roles were the

title-roles in Arabella and in Der Rosenkavalier (earlier in her

career, she had also sung the role of Sophie; when she finally added

the Marschallin to her repertoire, she became the first soprano in

history to have sung all three female lead roles in Der Rosenkavalier).

Her Puccini roles at the Vienna State Opera included the title-roles in

Tosca, Manon Lescaut, Madama Butterfly, Suor Angelica, Turandot, Mimi

in La Bohème and Giorgetta in Il Tabarro. In her 21 years with

the company, Lehmann sang more than fifty different roles at the Vienna

State Opera, including Marie/Marietta in Die tote Stadt, the

title-roles in La Juive by Fromental Halévy, Mignon by Ambroise

Thomas, and Manon by Jules Massenet, Charlotte in Werther, Marguerite

in Faust, Tatiana in Eugene Onegin and Lisa in The Queen of Spades. In

the meantime she had made her debut in London in 1914, and from 1924 to

1935 she performed regularly at the Royal Opera House, Covent Garden

where aside from her famous Wagner roles and the Marschallin she also

sang Desdemona in Otello and Donna Elvira in Don Giovanni. She appeared

regularly at the Salzburg Festival from 1926 to 1937, performing with

Arturo Toscanini, among other conductors. She also gave recitals there

accompanied at the piano by the conductor Bruno Walter. In August 1936,

while in Salzburg, she discovered the Trapp Family Singers, later made

famous in the musical The Sound of Music. Lehmann had heard of a villa

available for let and as she approached the villa she overheard the

family singing in their garden. Insisting the children had a precious

gift, she exclaimed that the family had "gold in their throats" and

that they should enter the Salzburg festival contest for group singing

the following night. Having regard to the family's aristocratic

background the Baron insisted performing in public was out of the

question, however Lehmann's fame and genuine enthusiasm persuaded the

Baron to relent, leading to their first public performance. After studying in Berlin with Mathilde Mallinger, she

made her debut at the Hamburg Opera in 1910 as a page in Wagner's

Lohengrin. In 1914, she gave her debut as Eva in Die Meistersinger von

Nürnberg at the Vienna Court Opera – the later Vienna State Opera

–, which she joined in 1916. She quickly established herself as one of

the company's brightest, most beloved stars in roles such as Elisabeth

in Tannhäuser and Elsa in Lohengrin. She created roles in the

world premieres of a number of operas by Richard Strauss, including the

Composer in Ariadne auf Naxos in 1916 (later she sang the title-role in

this opera), the Dyer's Wife in Die Frau ohne Schatten in 1919 and

Christine in Intermezzo in 1924. Her other Strauss roles were the

title-roles in Arabella and in Der Rosenkavalier (earlier in her

career, she had also sung the role of Sophie; when she finally added

the Marschallin to her repertoire, she became the first soprano in

history to have sung all three female lead roles in Der Rosenkavalier).

Her Puccini roles at the Vienna State Opera included the title-roles in

Tosca, Manon Lescaut, Madama Butterfly, Suor Angelica, Turandot, Mimi

in La Bohème and Giorgetta in Il Tabarro. In her 21 years with

the company, Lehmann sang more than fifty different roles at the Vienna

State Opera, including Marie/Marietta in Die tote Stadt, the

title-roles in La Juive by Fromental Halévy, Mignon by Ambroise

Thomas, and Manon by Jules Massenet, Charlotte in Werther, Marguerite

in Faust, Tatiana in Eugene Onegin and Lisa in The Queen of Spades. In

the meantime she had made her debut in London in 1914, and from 1924 to

1935 she performed regularly at the Royal Opera House, Covent Garden

where aside from her famous Wagner roles and the Marschallin she also

sang Desdemona in Otello and Donna Elvira in Don Giovanni. She appeared

regularly at the Salzburg Festival from 1926 to 1937, performing with

Arturo Toscanini, among other conductors. She also gave recitals there

accompanied at the piano by the conductor Bruno Walter. In August 1936,

while in Salzburg, she discovered the Trapp Family Singers, later made

famous in the musical The Sound of Music. Lehmann had heard of a villa

available for let and as she approached the villa she overheard the

family singing in their garden. Insisting the children had a precious

gift, she exclaimed that the family had "gold in their throats" and

that they should enter the Salzburg festival contest for group singing

the following night. Having regard to the family's aristocratic

background the Baron insisted performing in public was out of the

question, however Lehmann's fame and genuine enthusiasm persuaded the

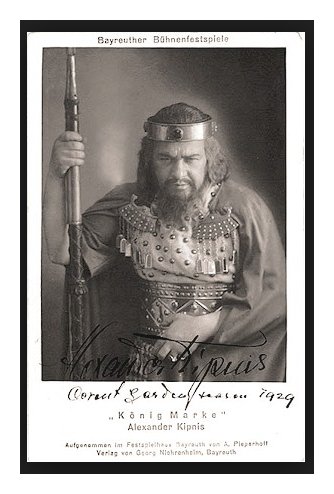

Baron to relent, leading to their first public performance.In 1930, Lehmann made her American debut in Chicago as Sieglinde in Wagner's Die Walküre. She returned to the United States every season and also performed several times in South America. Before Germany annexed Austria in 1938, Lehmann emigrated to the United States (because her stepchildren had a Jewish mother). There, she continued to sing at the San Francisco Opera and the Metropolitan Opera until 1945. In addition to her operatic work, Lehmann was a renowned singer of lieder, giving frequent recitals throughout her career. She also made a foray into film acting, playing the mother of Danny Thomas in Big City (1948), which also starred Robert Preston, George Murphy, Margaret O'Brien and Betty Garrett. After her retirement from the recital stage in 1951, Lehmann taught master classes at the Music Academy of the West in Santa Barbara, California, which she helped found in 1947. She also gave master classes in New York City (at the Manhattan School of Music), Chicago, London, Vienna, and other cities. For her contribution to the recording industry, Lehmann has a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame at 1735 Vine St. However, her first name is misspelled there as “Lottie”.  Alexander Kipnis first came to the USA in early 1923 as part of a large German/Wagnerian Opera Company that played for almost five months in the eastern and mid-western United States. This company showcased many veteran artists and some of the most important newer stars of the German operatic scene. Elsa Alsen and Meta Seinemeyer were among the sopranos. New York city hosted the company for a month at the Manhattan Opera House. Seinemeyer, about whom there is considerable interest, sang Senta, Sieglinde and Elizabeth; Alsen Isolde and Brunhilde; Jacques Urlus sang Tristan and Siegfried. Friedrich Schorr sang his first Hans Sachs and Wotans in New York during this season; Alexander Kipnis sang an average of four times a week in all the Wagner operas having a big bass role. Irving Kolodin in his History of the Metropolitan Opera noted that Schorr and Kipnis made the biggest impressions; Schorr was signed for the Met and Kipnis for Chicago.  Kipnis made his Chicago Opera debut November 18, 1923 as

the Wanderer in Kipnis made his Chicago Opera debut November 18, 1923 as

the Wanderer inSiegfried. As he was hired as a leading bass for the season, and as Chicago at this time did not have a large German repertoire component, he sang both leading and supporting roles; this pattern continued for five seasons, after which the German operas were staged more frequently and he was usually cast only in leading roles, with few exceptions. I have quickly put together a partial list of his leading and supporting roles. [Some would argue that some of these roles are really leading ones . . . . .] Walkuere: Wotan Andrea Chenier: Matheiu La Juive: Cardinal Aida: King Pelleas: Arkel Otello: Lodvico Tannhaeuser: Landgrave Konigskinder: Wood Cutter La Gioconda: Alvise Cleopatre: Enneus Carmen: Escamillo Thais: Palemon Rosenkavelier: Baron Ochs Jongleur Notre Dame: Prior Faust: Mephisto Propohete: Zacharias Lohengrin: King Henry Werther: Albert Tristan und Isolde: King Marke Don Giovanni: Commandant Tiefland: Tomaso Aida: Ramphis Meistersinger: Pogner Mefistofele: Mefistofele Fidelio: Rocco Bartered Bride: Kezal Parsifal: Gurnemanz Magic Flute: Sarastro Kipnis married Mildred Eleanor Levy of Chicago and took out his American citizenship papers there. [Their son was the harpsichordist Igor Kipnis.] In the German repertoire his name stands very large and always lends glamour to the casts, which after 1928 in Chicago featured Frida Leider, Lotte Lehmann, Maria Olczewska, Rudolf Bockelmann, and German singersof the highest calibre. In the Italian repertoire he was in casts that featured Claudia Muzio and Rosa Raisa, and in the French, Mary Garden. In 1924 the Chicago Opera completed a long tour to the West Coast. Among the featured soloists were Garden in Thais, Raisa in La Juive, Chaliapin in Boris Godunoff. On five occasions Kipnis sang Vaarlam to Chaliapin's Boris: Houston, Feb.28; San Francisco March 8, Portland March 11, Seattle March 15, and Kansas City March 22. Charles Mintzer -- Kipnis material from a

Listserv Opera-L Archives, Dec 28, 1999 (with additions and

corrections)

|

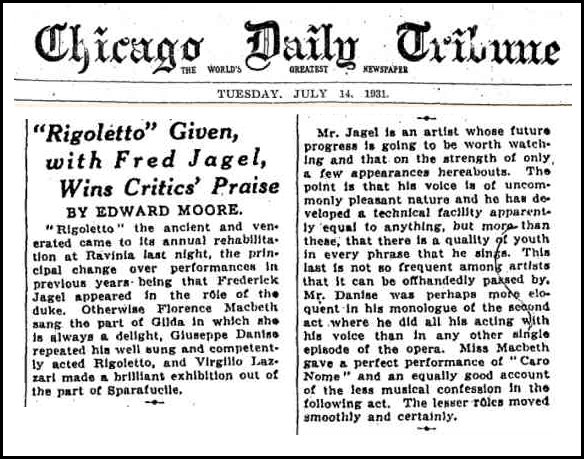

Frederick Jagel (June 10, 1897, Brooklyn, New York – July 5, 1982, San Francisco, California) was an American tenor, primarily active at the Metropolitan Opera in the 1930s and 1940s. Frederick Jagel studied voice in New York City and Milan, and made his debut as Rodolfo in La bohème, in Livorno, in 1924. He sang throughout Italy under the name of Federico Jaghelli. After his return to America, he made his debut at the Metropolitan Opera on November 8, 1927, as Radames in Aida. In 23 seasons with the Met, he sang 217 performances of 34 roles, primarily in the Italian and French repertories. He can be heard in many former Metropolitan Opera radio broadcasts, notably as Pollione in Norma, opposite Zinka Milanov, and Edgardo in Lucia di Lammermoor, opposite Lily Pons. Jagel also appeared in San Francisco, Chicago and Buenos Aires before retiring in 1950. He taught singing in New York after his retirement. Among his pupils were tenors Augusto Paglialunga, Robert Moulson and John Stewart and Bass-Baritone Justino Diaz. He also served as Chairman of the Voice Department at the New England Conservatory of Music in Boston. |

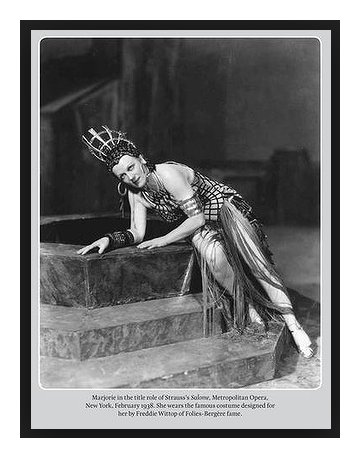

Marjorie

Florence Lawrence CBE (17 February 1907 – 13 January 1979) was an

Australian soprano, particularly noted as an interpreter of Richard

Wagner's operas. She was the first soprano to perform the immolation

scene in Götterdämmerung by riding her horse into the flames

as Wagner

had intended. Marjorie

Florence Lawrence CBE (17 February 1907 – 13 January 1979) was an

Australian soprano, particularly noted as an interpreter of Richard

Wagner's operas. She was the first soprano to perform the immolation

scene in Götterdämmerung by riding her horse into the flames

as Wagner

had intended. Lawrence's physicality and beauty made her popular with audiences – she performed the "Dance of the Seven Veils" in Richard Strauss's Salome more convincingly than most other sopranos. She was afflicted by polio from 1941. Lawrence later served on the faculty of the School of Music at Southern Illinois University Carbondale. During a performance in 1941 in Mexico, she was afflicted by polio. She returned to the stage 18 months later, performing in a chair, reclining or on a special platform. Although hampered by her lack of mobility, she continued to perform until 1952. In 1944, during World War II, she performed in charity concerts to entertain troops in Australia, seated in a chair. A performance as Amneris in Giuseppe Verdi's Aida in Paris in 1946 was well received as were concert appearances of Richard Strauss's Elektra in December 1947 with the Chicago Symphony Orchestra and Artur Rodzinski, but Lawrence left the stage, and instead began to work as a teacher. She served on the faculty of the School of Music at Southern Illinois University in Carbondale and then retired to her ranch, Harmony Hills, in Hot Springs, Arkansas where she taught international students. She later accepted students from the University of Arkansas at Little Rock from the late 1970s until her death in 1979. Her life story was told in the 1955 film Interrupted Melody, in which she was portrayed by Eleanor Parker, who was nominated for the Academy Award for Best Actress for her performance as Lawrence. |

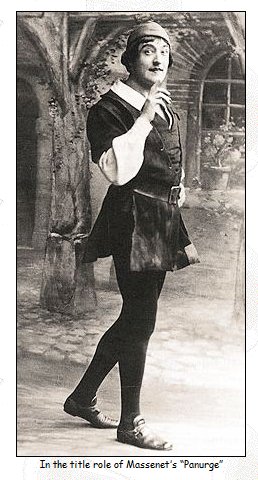

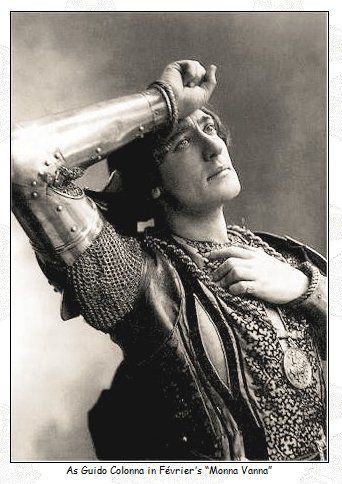

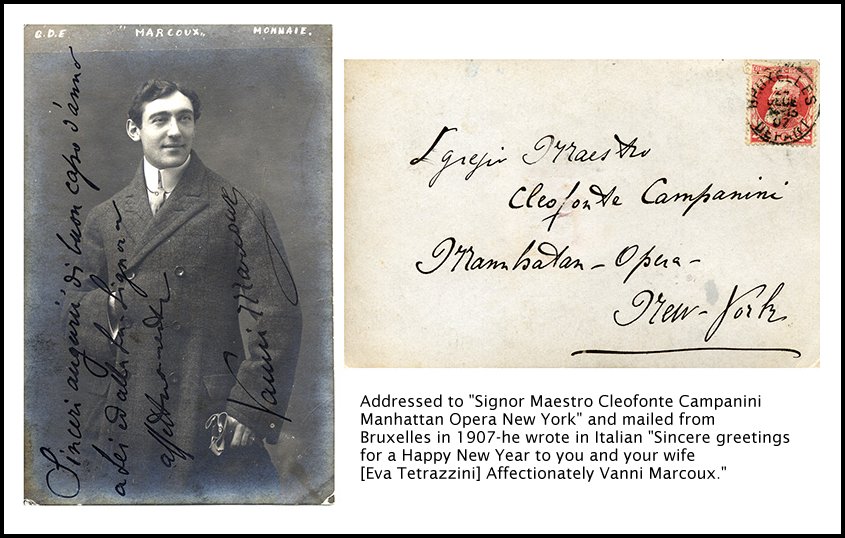

Vanni-Marcoux

was born Giovanni (Jean-Emile Diogène) Marcoux in 1877 in Turin.

Vanni, an

Italian abbrevation for Giovanni, reminds us that he was the son of a

French father and an Italian mother. He studied with Collini at his

hometown and with Frédéric Boyer at the Paris

Conservatoire. After

successfully completing law studies, Marcoux decided to devote himself

full to singing. His debut took place at Turin in 1894 as Sparafucile.

It was not until 1899 that he made his first stage appearance in

France, at Bayonne as Frère Laurent. Thereafter he toured a

number of

provincial theatres and was a guest at the La Monnaie in Brussels. In

1905 he debuted at Covent Garden as Basilio and returned there every

season until 1912, singing comprimario parts as well as Colline and

Sparafucile. Eventually he was given such parts like Arkel,

Marcel in Les Huguenots and

the Father in Charpentier’s Louise.

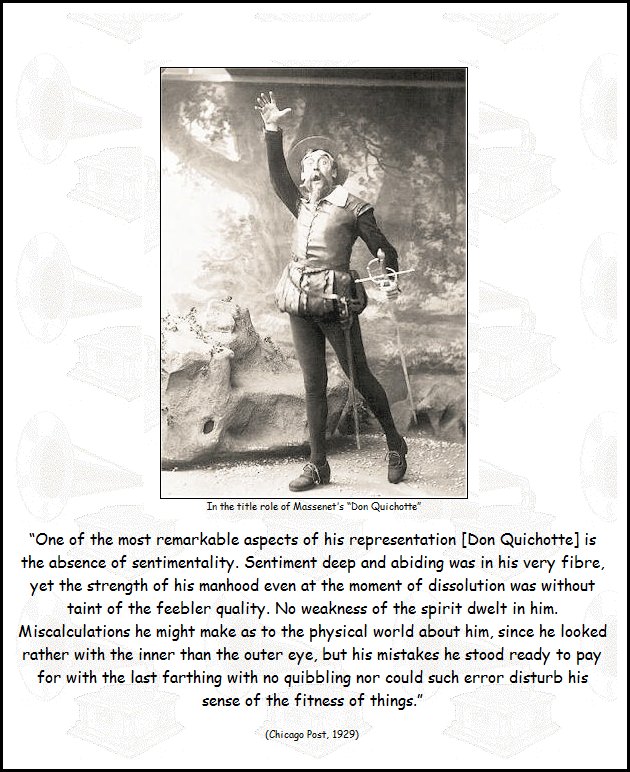

In 1909 he made

his debut at the Opéra Paris, creating Guido Colonna in Henri

Février’s Monna Vanna,

a role which brought him fame. Three years later he

appeared in the title role of Massenet’s Don Quichotte (probably his

greatest achievement). Massenet wrote his opera Panurge especially for

him. Its creation took place in 1913. Before World War I Vanni-Marcoux

was predominantly a bass, singing even Hunding and Fafner. For nearly

40 years he was a familiar and much admired figure in Parisian musical

life, mainly at the Opéra, but also at the Opéra-Comique,

creating a

number of roles in contemporary operas such as Gunsbourg’s Lysistrata,

d’Olonne’s L’Arlequin,

Février’s Monna Vanna

and La Femme nue, and

Honegger-Ibert’s L’Aiglon.

Subsequently he was engaged by Henry Russell to the Boston Opera where he established as a star. His first performance was in Pelléas et Mélisande, now as Golaud. His dramatic conception of Méphistophélès in Faust was also much admired by the public. The four roles in Les Contes d’Hoffmann (Coppélius, Dr. Miracle, Crespel, Dapertutto) belonged to his greatest histrionic achievements. Without doubt, Vanni-Marcoux owed much of his success in the United States to Mary Garden. Her popularisations of the works of the modern French composers soon provided him with all sort of dramatic opportunities. There was the rumour that he had divorced his second wife in order to marry Mary Garden. She declined, but she shared the stage with him in many performances of Thaïs, Tosca, Don Quichotte, Pelléas et Mélisande and Carmen. He followed her to Chicago in 1913 and was a regular guest there between 1926 and 1931. When Mary Garden finished her career, French opera could not survive without her, and thereafter there was no place for him. La Scala saw him as Boris (in French) under Arturo Toscanini and Sigismund Zaleski in 1922. He was generally regarded as the finest exponent of the role after Chaliapin. Paris invited him to sing the title role in the first French performance of Puccini’s Gianni Schicchi. From 1948 to 1951 Vanni-Marcoux was director of the Grand Théâtre at Bordeaux. He died in 1962.    |

|

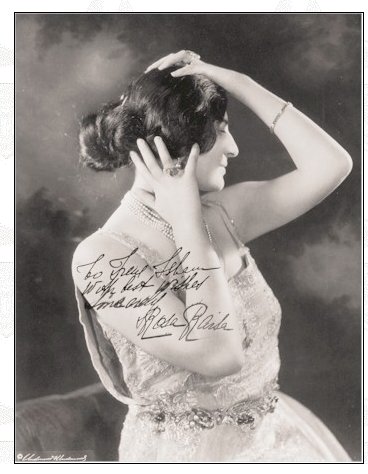

Rosa Raisa (30 May 1893 – 28

September 1963) was a Polish-born and Italian-trained Russian-Jewish

dramatic operatic soprano who became a naturalized American. She

possessed a voice of remarkable power and was the creator of Puccini’s

last opera, Turandot, at La Scala, Milan.

She was born Rosa Burchstein in Bialystock. When she was 14 she fled to escape a pogrom and settled in Napels. She studied with Barbara Marchisio and made her debut at Parma in the Verdi Centenary Oberto, being immediately invited by Cleofonte Campanini at Chicago Opera. She achieved instant success in Chicago, Philadelphia and on national tours. She remained in Chicago and was its leading dramatic soprano. Mary Garden reigned in the lyric parts. Raisa sang 275 performances in Chicago and 235 on tours. She inaugurated the new built Chicago Opera House in 1929 as Aida. Giacomo Puccini wanted her to sing Magda in La Rondine (!), but she refused. Whether he was more entranced with her youth and beauty or her vocal powers is unknown, but his plan for this assumption of Magda was advanced enough that in January 1917 she was announced in the world press for the premiere of this light opera in Monte Carlo. Raisa did not go to Monte Carlo as she was in the United States and was fearful of the submarine warfare at that stage of the Great War. Interestingly at about the same time Puccini first encountered Raisa, Arturo Toscanini heard her and told his friends in the opera world that he considered Raisa a “female Tamagno,” more appropriate for the heroic Turandot she would create nine years later. She was married to the baritone Giacomo Rimini. They appeared in many concerts singing duets from Luisa Miller to Don Pasquale (!). Her repertoire included roles in operas such as Norma, La Juive, La Fanciulla del West, Suor Angelica, Un Ballo in Maschera, La Battaglia di Legnano, Francesca da Rimini, Falstaff, Don Giovanni, Lohengrin, Tannhäuser, Les Huguenots, Lo Schiavo, Isabeau, La Nave, Die Fledermaus and Respighi’s La Fiamma.

|

© 1981 Bruce Duffie

This conversation was recorded at her home in Chicago on May

25, 1981. This transcription was made in 2016, and posted on this

website

at that time.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website, click here.

Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM, as well as on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio.

You are invited to visit his website for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.