SR: Not really. If I didn’t see it in a historical

perspective I might, but now that I see that this is sort of the ongoing process

of the way people are dealt with while we’re here, it’s simply par for the

course. That’s just the way things are.

SR: Not really. If I didn’t see it in a historical

perspective I might, but now that I see that this is sort of the ongoing process

of the way people are dealt with while we’re here, it’s simply par for the

course. That’s just the way things are. BD: You are often involved in the performance of

your pieces. Are you the ideal interpreter of your own music?

BD: You are often involved in the performance of

your pieces. Are you the ideal interpreter of your own music? SR: The bother is really more than just a bother.

To teach composition, you really have to project yourself into the minds of

the students, and that is a very arduous and difficult task. You have

to have a very wide, complete musicianship, and use every bit of it for the

benefit of the students. There are very few good teachers. Vincent

Persichetti comes to mind immediately. [See my Interview with Vincent

Persichetti.] Another is Hall Overton who was a jazz musician and

is no longer with us. But I don’t know if that is the ideal occupation

for a composer. Based on my experience, I would say it is certainly

not, and it was for that reason that I did not follow a university path.

Precisely the energies that are needed to write music are sopped up as blotter

paper in the process of teaching composition.

SR: The bother is really more than just a bother.

To teach composition, you really have to project yourself into the minds of

the students, and that is a very arduous and difficult task. You have

to have a very wide, complete musicianship, and use every bit of it for the

benefit of the students. There are very few good teachers. Vincent

Persichetti comes to mind immediately. [See my Interview with Vincent

Persichetti.] Another is Hall Overton who was a jazz musician and

is no longer with us. But I don’t know if that is the ideal occupation

for a composer. Based on my experience, I would say it is certainly

not, and it was for that reason that I did not follow a university path.

Precisely the energies that are needed to write music are sopped up as blotter

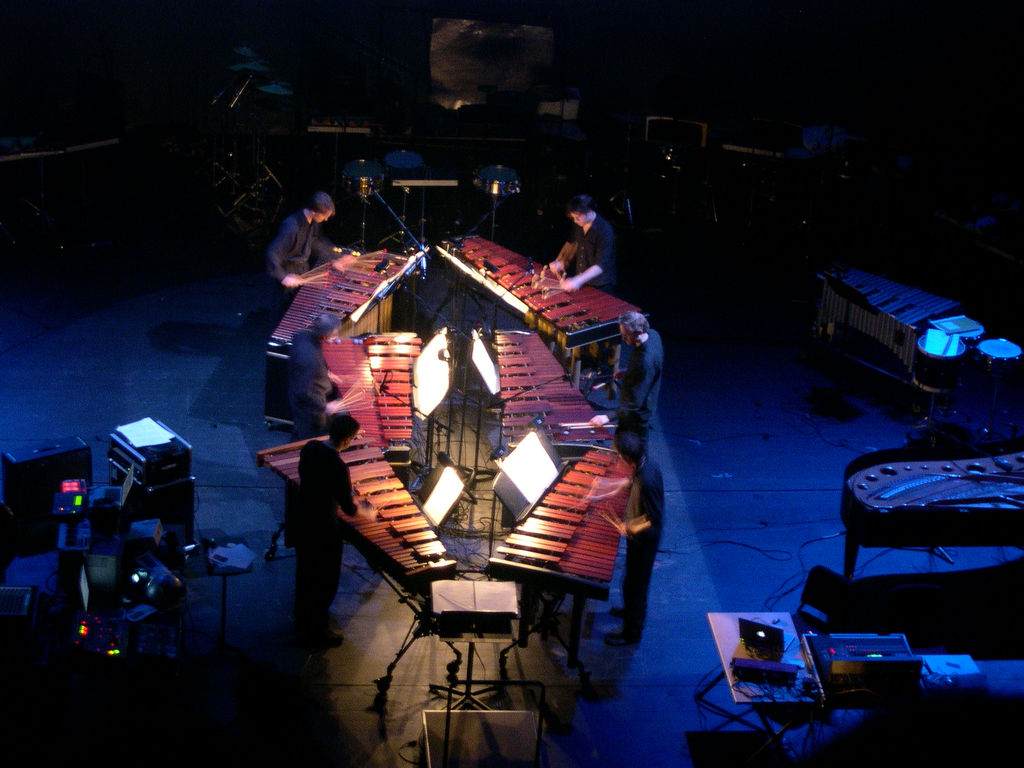

paper in the process of teaching composition. SR: That is definitely to be taken into consideration.

In more recent times, Ionisation

by Varèse used to take thirty or forty rehearsals, and was a very recherché situation. Now

every student percussion ensemble does it in less than a week. There

are certain inherent problems in what I do that have become increasingly

easier for musicians. I’ll tell you an amusing story about that.

Especially in percussion pieces, my ensemble will often try to economize

on instruments so that we don’t have to tour with too many. For instance,

Music for Mallet Instruments requires

four marimbas, but we have gotten it down to two by simply having one player

stand in back of the instrument. I’d written the part out and distributed

it so that one person is predominantly playing on the accidentals. It

also makes for a much more interesting way to play the piece; it’s like facing

your opponent for the game, and the rhythmic energy generated by that playing

situation is much more lively than simply playing on two separate instruments.

[Similar configuration shown at right; illustration of individual players

at each of six marimbas is shown farther below.] Later, when the piece

was done by John Adams and the San Francisco Symphony, I was curious to see

how they would do it. It’s a piece that my ensemble has done a great

deal, and I haven’t been around when it’s been done by others. The

parts that were sent out were for separate instruments, but then I saw in

the rehearsal that the two principal percussionists are facing each other

on the same instrument! I kind of cocked my head at one of them and

asked, “How come you’re playing like this? One of you is on the wrong

side of the instrument,” pretending to be dumb. He said, “We know how

you guys do it and it’s much more fun that way, so we redistributed the parts.”

[Both laugh] So I chalk that up to exactly what you’re talking about.

There’s a certain clarity that comes about the sort of polyrhythms that I

deal with, the problems that are presented by what doesn’t look to be too

difficult on paper, but in context turns out to be very difficult. It

is something that by musical osmosis seems to slowly take care of itself.

People get to know what those problems are. They become familiar with

non-Western music and the jazz inflections that are simply floating around

in the musical consciousness of a given generation. And lo and behold,

when you approach middle age, a lot of the orchestra which used to look like

your Grandpa, now begins to look like your children, and they have solved

a lot of the technical problems. These things take care of themselves

in that way. It would be very hard to nail down a coming awareness of

a newer style by musicians when they’re younger, and what the technical problems

are that are associated with that style. But because they become familiar

with it earlier on in their training, a lot of the solutions happen as if

without effort at all.

SR: That is definitely to be taken into consideration.

In more recent times, Ionisation

by Varèse used to take thirty or forty rehearsals, and was a very recherché situation. Now

every student percussion ensemble does it in less than a week. There

are certain inherent problems in what I do that have become increasingly

easier for musicians. I’ll tell you an amusing story about that.

Especially in percussion pieces, my ensemble will often try to economize

on instruments so that we don’t have to tour with too many. For instance,

Music for Mallet Instruments requires

four marimbas, but we have gotten it down to two by simply having one player

stand in back of the instrument. I’d written the part out and distributed

it so that one person is predominantly playing on the accidentals. It

also makes for a much more interesting way to play the piece; it’s like facing

your opponent for the game, and the rhythmic energy generated by that playing

situation is much more lively than simply playing on two separate instruments.

[Similar configuration shown at right; illustration of individual players

at each of six marimbas is shown farther below.] Later, when the piece

was done by John Adams and the San Francisco Symphony, I was curious to see

how they would do it. It’s a piece that my ensemble has done a great

deal, and I haven’t been around when it’s been done by others. The

parts that were sent out were for separate instruments, but then I saw in

the rehearsal that the two principal percussionists are facing each other

on the same instrument! I kind of cocked my head at one of them and

asked, “How come you’re playing like this? One of you is on the wrong

side of the instrument,” pretending to be dumb. He said, “We know how

you guys do it and it’s much more fun that way, so we redistributed the parts.”

[Both laugh] So I chalk that up to exactly what you’re talking about.

There’s a certain clarity that comes about the sort of polyrhythms that I

deal with, the problems that are presented by what doesn’t look to be too

difficult on paper, but in context turns out to be very difficult. It

is something that by musical osmosis seems to slowly take care of itself.

People get to know what those problems are. They become familiar with

non-Western music and the jazz inflections that are simply floating around

in the musical consciousness of a given generation. And lo and behold,

when you approach middle age, a lot of the orchestra which used to look like

your Grandpa, now begins to look like your children, and they have solved

a lot of the technical problems. These things take care of themselves

in that way. It would be very hard to nail down a coming awareness of

a newer style by musicians when they’re younger, and what the technical problems

are that are associated with that style. But because they become familiar

with it earlier on in their training, a lot of the solutions happen as if

without effort at all. SR: Lou is an interesting and somewhat eccentric

gentleman who I have real affection for. I work quite differently than

he does. In his case, and in the case of other composers of his generation,

there was an interest in taking the sounds of Indonesian music, and appropriating

them through tacked piano and various Western situations, and even creating

his own gamelan. I would run from that; I have leaned over backwards

to avoid that. My only interest in non-Western music, insofar as I’m

going to appropriate it, is to learn from it, see how I’m going to use it,

find out how it’s put together, its structure and so forth. For me,

the sounds of music, the scales and the timbres of the instruments, are something

that most of us learn when we are very young — even before we walked.

We are programmed to the scales on the piano keyboard. We are programmed

as to the sounds of the piano, violin, electric guitar that’s around us,

well before we’re able to play any music or say anything or form any conscious

activity. It always felt to me, on an intuitive level, that I was uncomfortable

with African and Balinese instruments. I think they’re gorgeous, but

I feel they tell a story. Their story is that they were born in such

and such a place, far, far away from here, that they were part of a very large

and very old musical history, and that that’s where they’re comfortable, that’s

where they belong and where they fit in. When I brought back some bells

from Africa, I started thinking about how I was going to tune them, and I

really can’t imagine myself with a metal file; it felt like kind of a musical

rape. So instead, I simply taught some of the musicians in my ensemble

how to play some bell patterns, using the African instruments to play African

music the way you would learn a piece of Scarlatti. It was to simply

get it out of my system. I had a lot of confirmation for ideas that

I had. For instance, two repeating patterns lined up so that their

downbeats do not coincide describes a lot of what I do, and it describes

a lot of what goes on in African music. The sound is wildly different.

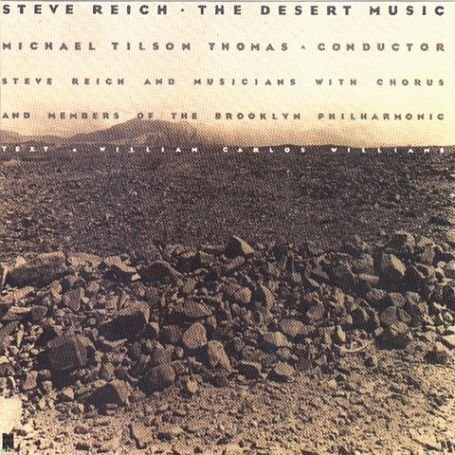

What you hear in African music and what you hear in the opening of The Desert Music couldn’t be further

apart, but there’s real community of structure there! Structure

is something that a musician learns later in life. You don’t learn

about canon or sonata allegro form when you’re three months old. A

precocious child would learn that at four or five, which would be astoundingly

early. That’s the kind of thing you pick up when you’re in your teens,

and for that very reason, those kinds of ideas can travel more easily because

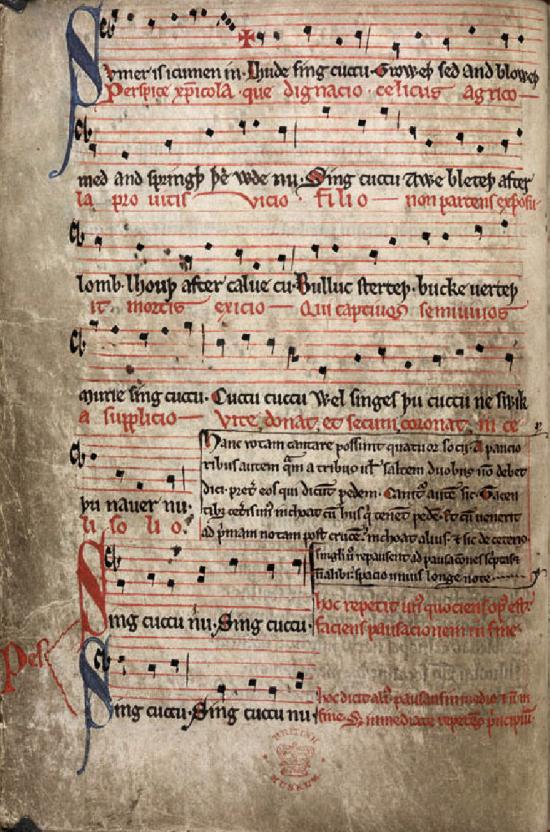

they are about organizing sounds. The idea of canon, for instance, is

the basic idea of imitative counterpoint. It props up about the thirteenth

century in Sumer Is Icumen In

[photo of score at right] and runs throughout the Baroque period.

You can hear canons again in Webern in the Symphony; we heard them in the Bartók

quartets and in his piano music; and we hear them in my music. All those

musics sound wildly different, but the canon is such a neutral technique.

It’s like a glass — you can put in wine or Pepsi-Cola or whatever you like.

It doesn’t tell you about its sound contents, it is simply an abstract idea,

and a very, very durable one at that. That’s precisely what I look for

in non-Western music, which has many procedures very close to canon.

SR: Lou is an interesting and somewhat eccentric

gentleman who I have real affection for. I work quite differently than

he does. In his case, and in the case of other composers of his generation,

there was an interest in taking the sounds of Indonesian music, and appropriating

them through tacked piano and various Western situations, and even creating

his own gamelan. I would run from that; I have leaned over backwards

to avoid that. My only interest in non-Western music, insofar as I’m

going to appropriate it, is to learn from it, see how I’m going to use it,

find out how it’s put together, its structure and so forth. For me,

the sounds of music, the scales and the timbres of the instruments, are something

that most of us learn when we are very young — even before we walked.

We are programmed to the scales on the piano keyboard. We are programmed

as to the sounds of the piano, violin, electric guitar that’s around us,

well before we’re able to play any music or say anything or form any conscious

activity. It always felt to me, on an intuitive level, that I was uncomfortable

with African and Balinese instruments. I think they’re gorgeous, but

I feel they tell a story. Their story is that they were born in such

and such a place, far, far away from here, that they were part of a very large

and very old musical history, and that that’s where they’re comfortable, that’s

where they belong and where they fit in. When I brought back some bells

from Africa, I started thinking about how I was going to tune them, and I

really can’t imagine myself with a metal file; it felt like kind of a musical

rape. So instead, I simply taught some of the musicians in my ensemble

how to play some bell patterns, using the African instruments to play African

music the way you would learn a piece of Scarlatti. It was to simply

get it out of my system. I had a lot of confirmation for ideas that

I had. For instance, two repeating patterns lined up so that their

downbeats do not coincide describes a lot of what I do, and it describes

a lot of what goes on in African music. The sound is wildly different.

What you hear in African music and what you hear in the opening of The Desert Music couldn’t be further

apart, but there’s real community of structure there! Structure

is something that a musician learns later in life. You don’t learn

about canon or sonata allegro form when you’re three months old. A

precocious child would learn that at four or five, which would be astoundingly

early. That’s the kind of thing you pick up when you’re in your teens,

and for that very reason, those kinds of ideas can travel more easily because

they are about organizing sounds. The idea of canon, for instance, is

the basic idea of imitative counterpoint. It props up about the thirteenth

century in Sumer Is Icumen In

[photo of score at right] and runs throughout the Baroque period.

You can hear canons again in Webern in the Symphony; we heard them in the Bartók

quartets and in his piano music; and we hear them in my music. All those

musics sound wildly different, but the canon is such a neutral technique.

It’s like a glass — you can put in wine or Pepsi-Cola or whatever you like.

It doesn’t tell you about its sound contents, it is simply an abstract idea,

and a very, very durable one at that. That’s precisely what I look for

in non-Western music, which has many procedures very close to canon. SR: I won’t be around to see that, will I?

All I can do is the very, very best I can, and I’ll say I certainly hope that

it will last as long as we have a history in front of us. I hope that

we have a history in front of us, and I hope that I’ll be a part of it.

SR: I won’t be around to see that, will I?

All I can do is the very, very best I can, and I’ll say I certainly hope that

it will last as long as we have a history in front of us. I hope that

we have a history in front of us, and I hope that I’ll be a part of it. SR: That there are aspects of that. It may

also be my taste in musical history. For someone who doesn’t care for

any kind of bel canto opera, and who appreciates the kind of vocal sound that

you would get years ago from someone like Marni Nixon — the

small, non-vibrato voice — I’ve gravitated to that sound in the chorus of

The Desert Music. It’s in Tehillim as well. The people who

sing actually come from Musica Sacra, from the Waverly Consort, old-music

people in New York City. I have had dealings with these people for many,

many years now. Van Harmis, who runs Calliope, was in my ensemble.

That kind of sound, if it’s going to be put in a context where there’s a

lot of percussion, will have to be amplified. Some people could see

that as a kind of crutch; I see it as exactly what I want to hear. The

detail that comes through on recording is something that I crave in performance.

My music is very intricate, and in recording we do it on multi-track.

I talked a lot about that multi-track procedure (which originated in rock

and roll) with Peter Clancy from Nonesuch. I find it marvelous for recording

an orchestra piece like The Desert Music!

We used almost fifty mikes in that piece. Paul Goodman, who ran the

RCA Studio A, told me he thought it was the largest session he had ever seen

in that room — not in terms of forces, which it was;

it was a hundred sixteen people — but in numbers of microphones. That

was not capricious. That was to get that on-mike, close detailed sound

all the way through the string section. In certain kinds of music,

particularly nineteenth century music, one doesn’t want that. One wants

the depth and sort of indefinite, dark brown edges of the music to blur.

That’s the richness of sound that you want there. That’s appropriate

to that style. For what I do, that’s not appropriate. I want

the detail of a large ensemble to come through all around you, as if you

were sitting right where the conductor is.

SR: That there are aspects of that. It may

also be my taste in musical history. For someone who doesn’t care for

any kind of bel canto opera, and who appreciates the kind of vocal sound that

you would get years ago from someone like Marni Nixon — the

small, non-vibrato voice — I’ve gravitated to that sound in the chorus of

The Desert Music. It’s in Tehillim as well. The people who

sing actually come from Musica Sacra, from the Waverly Consort, old-music

people in New York City. I have had dealings with these people for many,

many years now. Van Harmis, who runs Calliope, was in my ensemble.

That kind of sound, if it’s going to be put in a context where there’s a

lot of percussion, will have to be amplified. Some people could see

that as a kind of crutch; I see it as exactly what I want to hear. The

detail that comes through on recording is something that I crave in performance.

My music is very intricate, and in recording we do it on multi-track.

I talked a lot about that multi-track procedure (which originated in rock

and roll) with Peter Clancy from Nonesuch. I find it marvelous for recording

an orchestra piece like The Desert Music!

We used almost fifty mikes in that piece. Paul Goodman, who ran the

RCA Studio A, told me he thought it was the largest session he had ever seen

in that room — not in terms of forces, which it was;

it was a hundred sixteen people — but in numbers of microphones. That

was not capricious. That was to get that on-mike, close detailed sound

all the way through the string section. In certain kinds of music,

particularly nineteenth century music, one doesn’t want that. One wants

the depth and sort of indefinite, dark brown edges of the music to blur.

That’s the richness of sound that you want there. That’s appropriate

to that style. For what I do, that’s not appropriate. I want

the detail of a large ensemble to come through all around you, as if you

were sitting right where the conductor is. SR: [Leaning into the microphone for a DJ-type

of sound] Tune in now, you all, wherever you are!

SR: [Leaning into the microphone for a DJ-type

of sound] Tune in now, you all, wherever you are! SR: No, I think either one is just deadly.

I believe a concert is a concert is a concert. You come in, you sit

down, they play the music; you listen to it, you love it, you hate it, you

leave, period. Later, or well before but preferably later; the next

day, that is. This is what we actually do as an ensemble when we tour,

and what I do when I’m asked to do these things, if I can possibly control

the situation. Let’s say you’re at University X or at City Y.

The day after the concert, in the afternoon, I basically will play recordings

of something that was not on the program, pass out the score of what was on

the program and what is being played on the recordings, and then answer any

and all questions. It’s usually much better than simply presenting your

own ideas to people who you’re not sure if that’s really what they want to

hear or not. I really do enjoy doing that. You can say a great

deal about music, but to say it at the time of the concert accomplishes two

things — it kills the concert and blurs the content

of what you’re saying, and turns it into an apologetic which becomes highly

emotionally charged and doesn’t get any information across. It’s the

worst of all possible worlds. People learn nothing, nor do they have

any joy in the concert.

SR: No, I think either one is just deadly.

I believe a concert is a concert is a concert. You come in, you sit

down, they play the music; you listen to it, you love it, you hate it, you

leave, period. Later, or well before but preferably later; the next

day, that is. This is what we actually do as an ensemble when we tour,

and what I do when I’m asked to do these things, if I can possibly control

the situation. Let’s say you’re at University X or at City Y.

The day after the concert, in the afternoon, I basically will play recordings

of something that was not on the program, pass out the score of what was on

the program and what is being played on the recordings, and then answer any

and all questions. It’s usually much better than simply presenting your

own ideas to people who you’re not sure if that’s really what they want to

hear or not. I really do enjoy doing that. You can say a great

deal about music, but to say it at the time of the concert accomplishes two

things — it kills the concert and blurs the content

of what you’re saying, and turns it into an apologetic which becomes highly

emotionally charged and doesn’t get any information across. It’s the

worst of all possible worlds. People learn nothing, nor do they have

any joy in the concert. SR: Sometimes, sure! Absolutely, yes.

Late at night I’ll put it on when I get ready to go to bed, sometimes.

Or if I’m in a hotel that has it, yeah. I don’t sit in front of it

for hours. There are teenagers who have that as the wallpaper of their

room! I’m curious to see what goes on around me. I can imagine

people hating it, and they’re absolutely right about ninety percent of it.

But it’s like taking the pulse of the life around you. I don’t want

to be an ostrich; I don’t think we gain anything by that. You can reject

it totally, and most of it is, indeed, prime grist for the mill, but better

to reject what you’ve seen, rather than just to know that it exists and think

it’s going to give you the creeps — which it probably will! [Laughs]

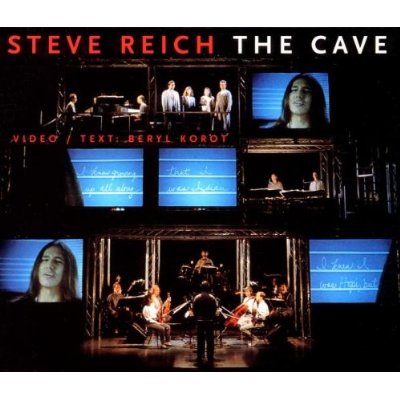

I think “music theater” is a much

more; it is a term to accommodate all the new forms that are arising now,

where the word opera seems somehow misplaced. I, personally, don’t enjoy

the opera from Mozart through Wagner, and very little besides that.

The operas I enjoy are The Rake’s Progress,

Threepenny Opera, a little bit of

Bluebeard’s Castle, some Monteverdi,

and that’s about it.

SR: Sometimes, sure! Absolutely, yes.

Late at night I’ll put it on when I get ready to go to bed, sometimes.

Or if I’m in a hotel that has it, yeah. I don’t sit in front of it

for hours. There are teenagers who have that as the wallpaper of their

room! I’m curious to see what goes on around me. I can imagine

people hating it, and they’re absolutely right about ninety percent of it.

But it’s like taking the pulse of the life around you. I don’t want

to be an ostrich; I don’t think we gain anything by that. You can reject

it totally, and most of it is, indeed, prime grist for the mill, but better

to reject what you’ve seen, rather than just to know that it exists and think

it’s going to give you the creeps — which it probably will! [Laughs]

I think “music theater” is a much

more; it is a term to accommodate all the new forms that are arising now,

where the word opera seems somehow misplaced. I, personally, don’t enjoy

the opera from Mozart through Wagner, and very little besides that.

The operas I enjoy are The Rake’s Progress,

Threepenny Opera, a little bit of

Bluebeard’s Castle, some Monteverdi,

and that’s about it. BD: And it turned into a paying proposition?

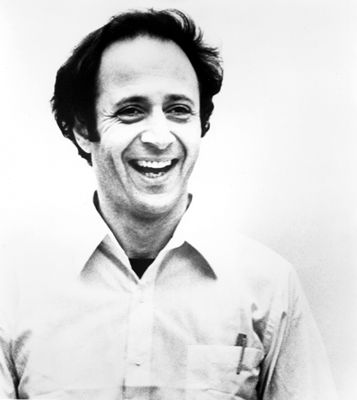

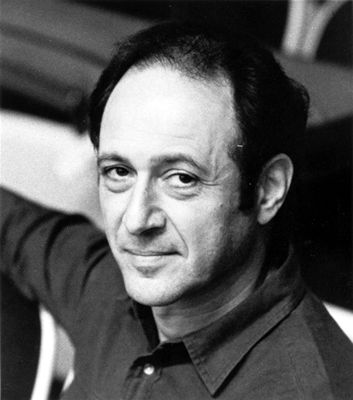

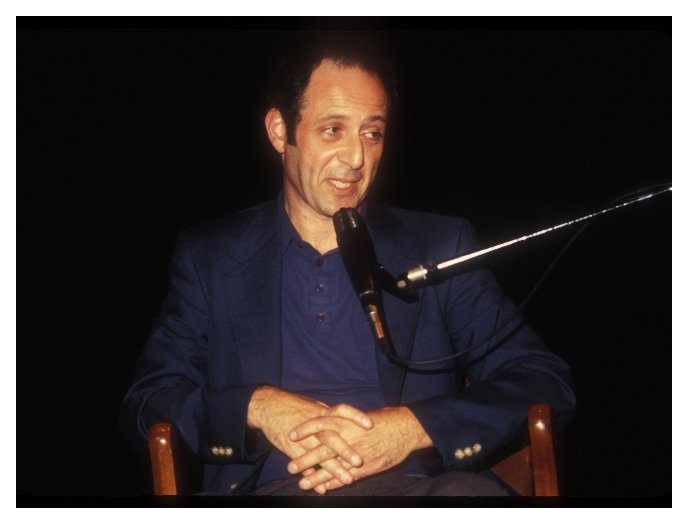

BD: And it turned into a paying proposition? SR: What really happened first was Different Trains. In 1985 I got

a commission from Betty Freeman to do a piece for Kronos Quartet, and the

video artist Beryl Korot [photo with Reich at right] said to

me in about 1987, “Why don’t you use the sampling keyboard for Kronos?

They’ll love it, and you’re dying to use it.” So I did this piece which

introduced this idea of people speaking and musical instruments playing their

speech melody. I had been asked to do operas in the late 1970’s and

early 1980’s in Holland Festival and the Frankfurt Opera, and I said no.

SR: What really happened first was Different Trains. In 1985 I got

a commission from Betty Freeman to do a piece for Kronos Quartet, and the

video artist Beryl Korot [photo with Reich at right] said to

me in about 1987, “Why don’t you use the sampling keyboard for Kronos?

They’ll love it, and you’re dying to use it.” So I did this piece which

introduced this idea of people speaking and musical instruments playing their

speech melody. I had been asked to do operas in the late 1970’s and

early 1980’s in Holland Festival and the Frankfurt Opera, and I said no. SR: I never thought of such a thing in my life,

and you know, I’m not a techno nut! [Both laugh]

SR: I never thought of such a thing in my life,

and you know, I’m not a techno nut! [Both laugh] BD: How is someone supposed to be able to take

all this in at one shot?

BD: How is someone supposed to be able to take

all this in at one shot? SR: Absolutely, absolutely! I’m a practical

musician and always have been. I’ve been, as you well know, a member

of a performing ensemble, which is heard on this recording. I’ve worked

with many other ensembles and I’m keenly aware of the realities when you’re

touring. I work with woodwind players who double on instruments, because

you can travel with two people rather than four or six. [Illustration

of stage-space required for individual forces at right.] And I dare

say, if you go back and look at the ins and outs of the different performances

of Messiah way back when, a lot

of those were exactly the same considerations — who

was in town, who was sick, who didn’t like him anymore, and blah, blah, blah.

This has affected music since music existed because music is people getting

together and playing. That said, Beryl and I are going to do a new

work in 1997. It’s commissioned by the city of Bonn and the city of

Cologne, and we’re going to work on one screen because one screen means it

travels and has legs, and more than one means it doesn’t! So constraint

will be on her side, and she has to deal with the fact that she wants to

do this kind of contrapuntal video in one screen. Fortunately she now

has most of the video in a computerized form, in a digital form, whereby

you can have multiple layers and multiple things going on within one screen.

She can enlarge something, transfer it to film, do it on one screen and still

have the basic lynchpin connection between her work and my work, i.e. the

kind of contrapuntal images and contrapuntal music that literally interlock.

What subject matter it will be for the new piece I have no idea, but we will

have an idea, I would say, about six months from now, because that’s when

we’ve got to begin! [Laughs]

SR: Absolutely, absolutely! I’m a practical

musician and always have been. I’ve been, as you well know, a member

of a performing ensemble, which is heard on this recording. I’ve worked

with many other ensembles and I’m keenly aware of the realities when you’re

touring. I work with woodwind players who double on instruments, because

you can travel with two people rather than four or six. [Illustration

of stage-space required for individual forces at right.] And I dare

say, if you go back and look at the ins and outs of the different performances

of Messiah way back when, a lot

of those were exactly the same considerations — who

was in town, who was sick, who didn’t like him anymore, and blah, blah, blah.

This has affected music since music existed because music is people getting

together and playing. That said, Beryl and I are going to do a new

work in 1997. It’s commissioned by the city of Bonn and the city of

Cologne, and we’re going to work on one screen because one screen means it

travels and has legs, and more than one means it doesn’t! So constraint

will be on her side, and she has to deal with the fact that she wants to

do this kind of contrapuntal video in one screen. Fortunately she now

has most of the video in a computerized form, in a digital form, whereby

you can have multiple layers and multiple things going on within one screen.

She can enlarge something, transfer it to film, do it on one screen and still

have the basic lynchpin connection between her work and my work, i.e. the

kind of contrapuntal images and contrapuntal music that literally interlock.

What subject matter it will be for the new piece I have no idea, but we will

have an idea, I would say, about six months from now, because that’s when

we’ve got to begin! [Laughs] BD: Do you try to emulate Bach in any other way?

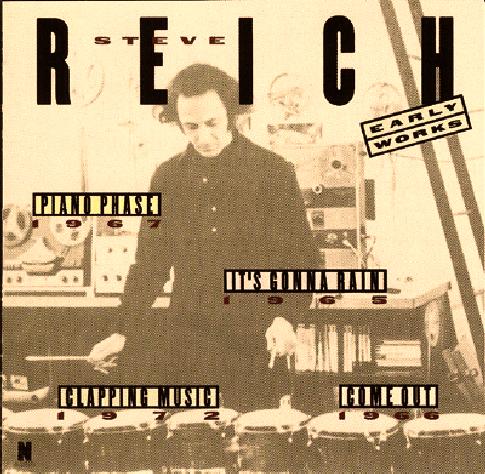

BD: Do you try to emulate Bach in any other way?| Steve Reich has been called

"...America's greatest living composer." (The Village VOICE), "...the

most original musical thinker of our time" (The New Yorker) and "...among

the great composers of the century" (The New York Times). From his

early taped speech pieces It's Gonna Rain (1965) and Come Out

(1966) to his and video artist Beryl Korot's digital video opera Three

Tales (2002), Mr. Reich's path has embraced not only aspects of Western

Classical music, but the structures, harmonies, and rhythms of non-Western

and American vernacular music, particularly jazz. "There's just a handful

of living composers who can legitimately claim to have altered the direction

of musical history and Steve Reich is one of them," states The Guardian

(London). Over the years, Steve Reich has received commissions from the Barbican Centre London; the Holland Festival; San Francisco Symphony; the Rothko Chapel; Vienna Festival; Hebbel Theater, Berlin; the Brooklyn Academy of Music for guitarist Pat Metheny; Spoleto Festival USA; West German Radio, Cologne; Settembre Musica, Torino; the Fromm Music Foundation for clarinetist Richard Stoltzman; the Saint Louis Symphony Orchestra; Betty Freeman for the Kronos Quartet; and the Festival d'Automne, Paris, for the 200th anniversary of the French Revolution. Steve Reich's music has been performed by major orchestras and ensembles around the world, including the London Symphony Orchestra conducted by Michael Tilson Thomas; New York Philharmonic conducted by Zubin Mehta; the San Francisco Symphony conducted by Michael Tilson Thomas; The Ensemble Modern conducted by Bradley Lubman; The Ensemble Intercontemporain conducted by David Robertson; the London Sinfonietta conducted by Markus Stenz and Martyn Brabbins; the Los Angeles Philharmonic conducted by Neal Stulberg; the BBC Symphony conducted by Peter Eötvös; and the Boston Symphony Orchestra conducted by Michael Tilson Thomas. In 1994 Steve Reich was elected to the American Academy of Arts and Letters, to the Bavarian Academy of Fine Arts in 1995, and, in 1999, awarded Commandeur de l'ordre des Arts et Lettres. The year 2000 brought four additional honors: the Schuman Prize from Columbia University, the Montgomery Fellowship from Dartmouth College, the Regent's Lectureship at the University of California at Berkeley, and an honorary doctorate from the California Institute of the Arts. In 2007, Mr. Reich was awarded the Polar Music Prize by the Swedish Academy of Music. In April of 2009 Steve Reich won his first-ever Pulitzer Prize for Double Sextet (2007). Commissioned by eighth blackbird, the 22-minute piece received its world premiere on March 26, 2008 at the University of Richmond’s Modlin Center for the Arts in Virginia. Scored for two each of flutes, clarinets, vibraphones, pianos, violins and cellos, Double Sextet can be played in two ways; either with twelve musicians or with six playing against a recording of themselves. In 2008, Reich wrote his first piece for rock band set-up, 2x5, which premiered on the opening night of Manchester International Festival on a double-bill with German electronic music legends Kraftwerk. Steve Reich is published by Boosey & Hawkes. - May 2010

Reprinted by kind permission of Boosey

& Hawkes

|

These interviews were recorded in Chicago on October 9, 1985, and

November 9, 1995. Portions (along with recordings) were used on WNIB

in 1986, 1991, and 1996. This transcription was made and posted on this

website in 2010.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website, click here.

Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM.

You are invited to visit his website for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.