|

Rolf Smedvig (September 23, 1952 in Seattle, Washington - April 27, 2015

in West Stockbridge, Massachusetts) came from a musical family. His father

Egil Steinar Smedvig (1922-2012) was a composer and music teacher who had

immigrated from Stavanger, Norway. His mother Kristin (Jonsson) Smedvig (1921-2004)

was member of the Seattle Symphony's violin section who had immigrated from

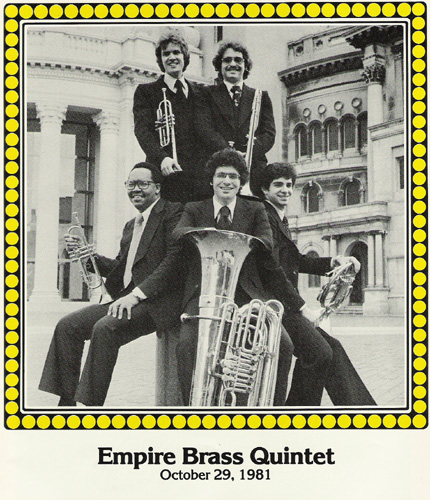

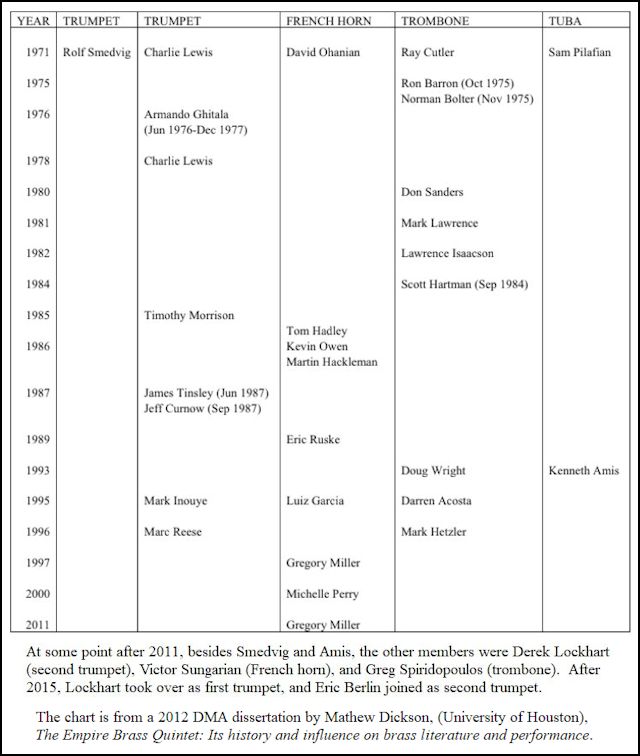

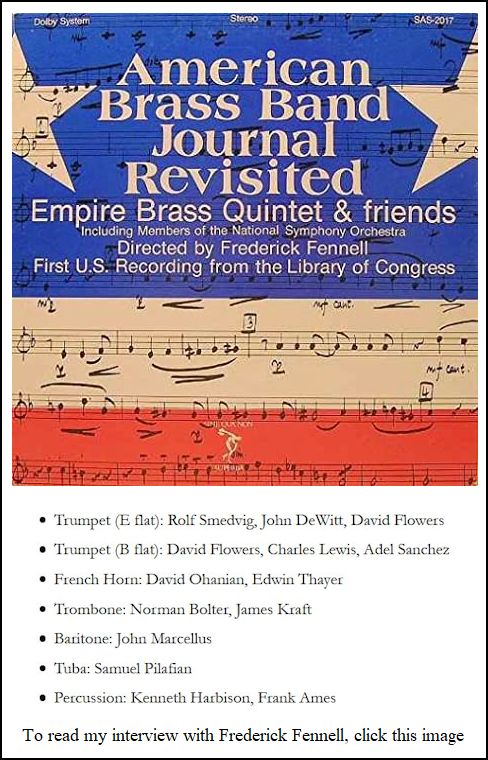

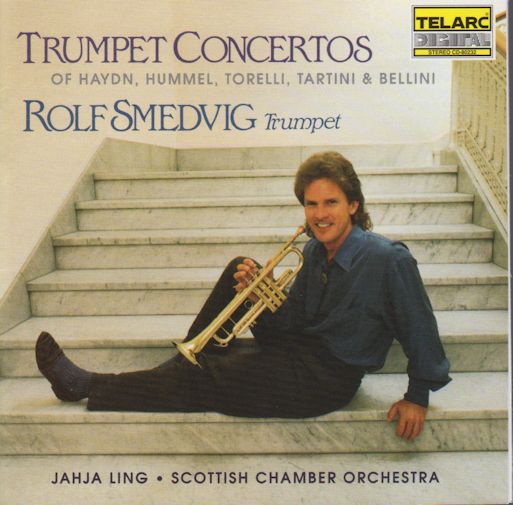

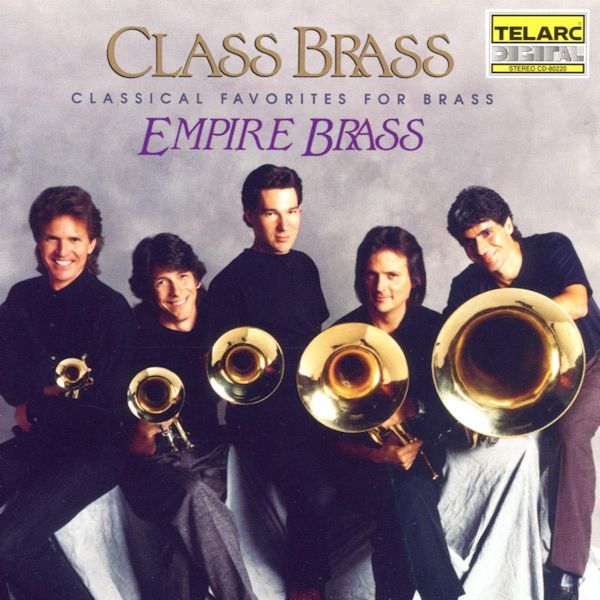

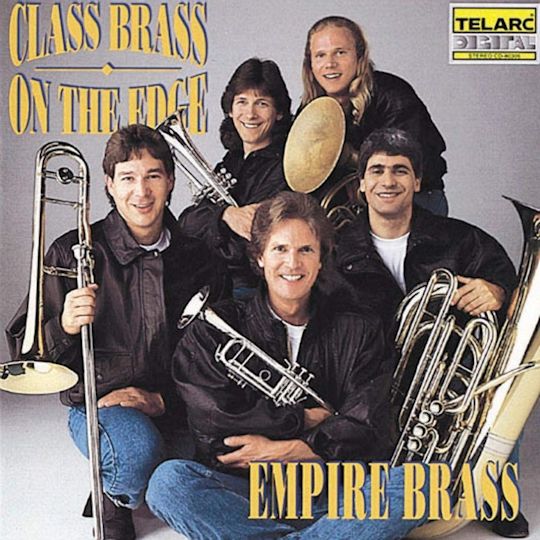

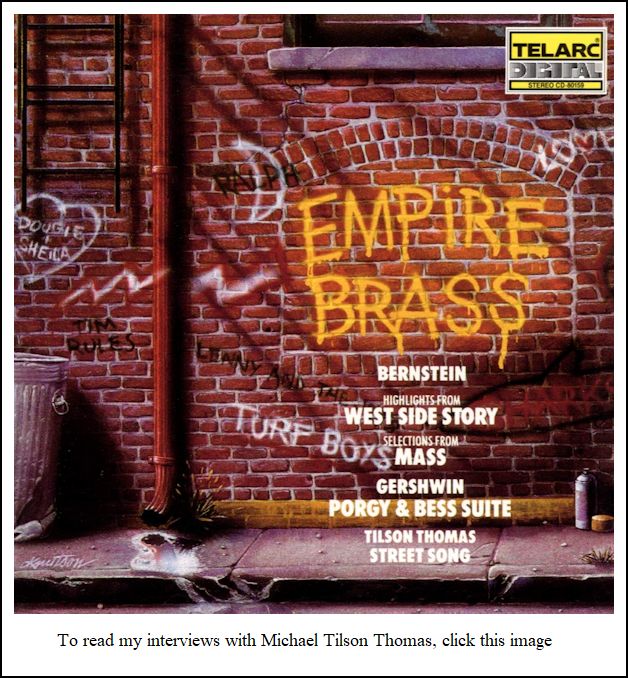

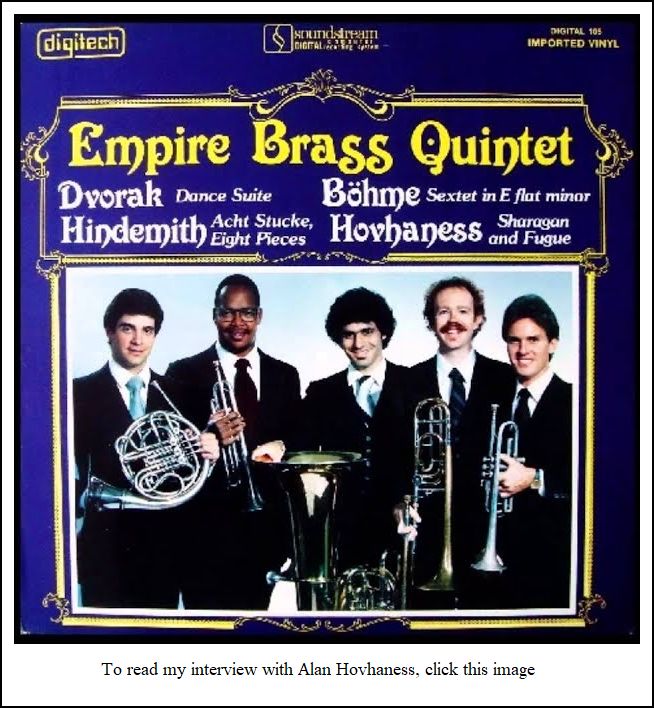

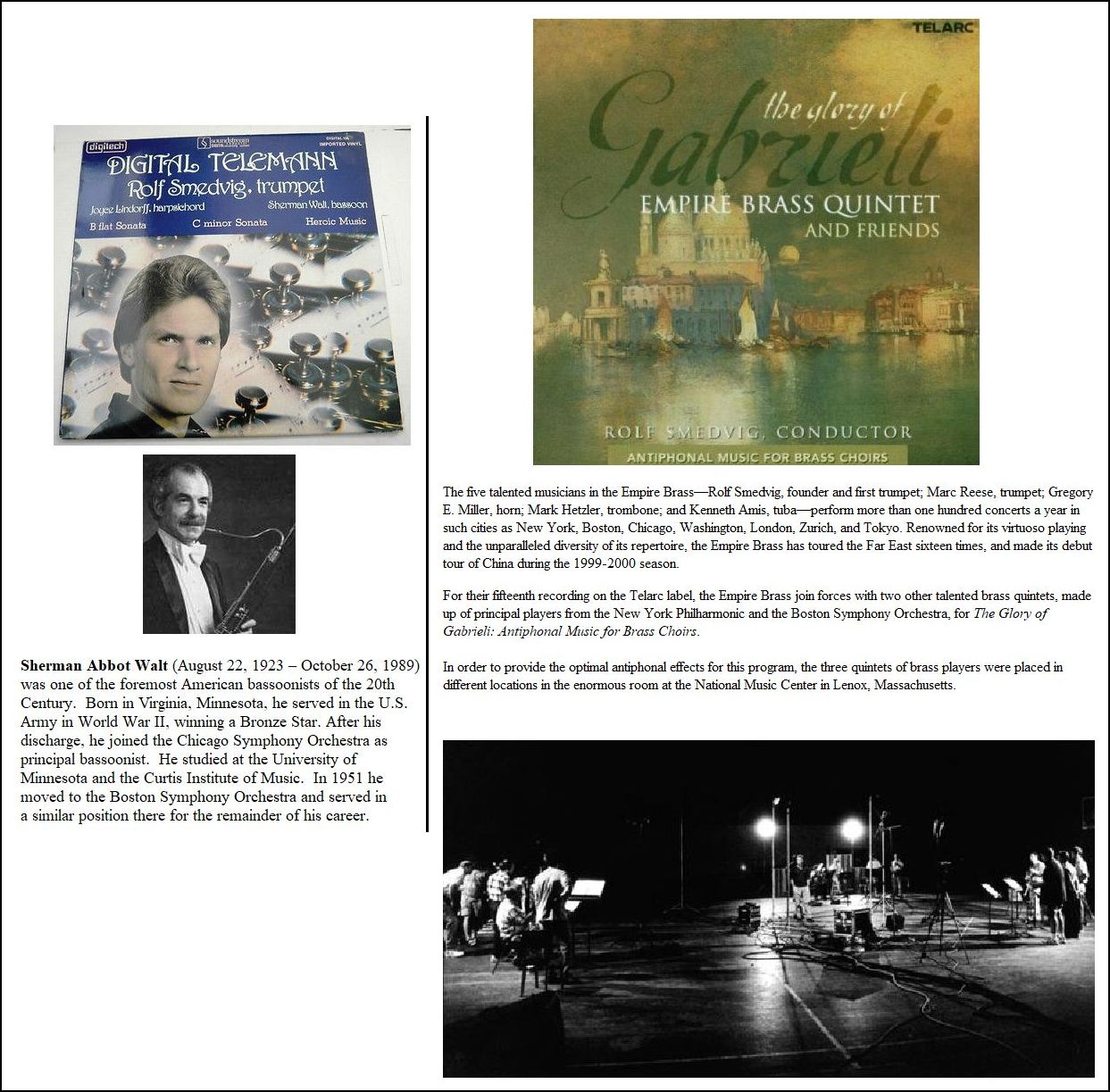

Iceland. In 1965, at age 13, Smedvig joined the Seattle Youth Symphony Orchestras as their principal trumpet. In 1971, he participated in the summer music program at the Tanglewood Music Center. While there, Smedvig, along with trumpeter Charles Lewis, hornist Paul Capehart, trombonist Ray Cutler, and tubist Samuel Pilafian were assembled into a chamber group to perform Gunther Schuller's Music for Brass Quintet. Following Tanglewood, Leonard Bernstein chose Smedvig, Lewis, and Pilafian to be solists for the 1971 world premiere of his composition Mass which was written for the opening of the John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts. Smedvig studied music under the tutelage of Armando Ghitalla at Boston University, where Smedvig later served as an instructor. In 1971, aged 19, Smedvig joined the Boston Symphony as assistant principal trumpet. At the time, Smedvig was the youngest member of the orchestra. He was promoted to principal trumpet in 1979, and left in 1981 to focus on a solo career, conducting, and chamber music. Smedvig co-founded the Empire Brass quintet in 1972. The Empire Brass served as Faculty Quintet-in-Residence at Boston University for a number of years. The group was the first brass quintet to win a Walter W. Naumburg Foundation award. |

Smedvig: It’s a magical combination,

and that has to do with what the individual player hears. I’ve

always consciously thought of myself as a singer. I’ve never

really thought of myself as anything other than that. I don’t

really speak words, but I can make attempts at putting vibrato on, or

putting characteristic sounds in my sound and in my tone. Where

words cannot convey a certain emotion, I can get that emotion out with

the sound of my trumpet through singing, or making attempts at singing.

The best performances that I’ve ever given are usually when I’m

really not thinking about it. The phrases and the little so-called

tools that a musician uses to make little inflections make the music come

alive from these little black notes on the page. I could play something

simple, like Row, Row, Row Your Boat, many different ways, using

articulation, using vibrato, using these magical little tools.

We learn in a practice room how to do it, but then, after a while, it

becomes second nature. You’re really not even thinking about

it. It would be like a gymnast having to start thinking, “OK, now

I’m going to jump up in the air and do three somersaults, and I’m going

to land, and I’m going to stretch my hands out, and I’m going to make this

beautiful formation at the end of it.” You can’t do that. It

has to be natural, like catching a ball.

Smedvig: It’s a magical combination,

and that has to do with what the individual player hears. I’ve

always consciously thought of myself as a singer. I’ve never

really thought of myself as anything other than that. I don’t

really speak words, but I can make attempts at putting vibrato on, or

putting characteristic sounds in my sound and in my tone. Where

words cannot convey a certain emotion, I can get that emotion out with

the sound of my trumpet through singing, or making attempts at singing.

The best performances that I’ve ever given are usually when I’m

really not thinking about it. The phrases and the little so-called

tools that a musician uses to make little inflections make the music come

alive from these little black notes on the page. I could play something

simple, like Row, Row, Row Your Boat, many different ways, using

articulation, using vibrato, using these magical little tools.

We learn in a practice room how to do it, but then, after a while, it

becomes second nature. You’re really not even thinking about

it. It would be like a gymnast having to start thinking, “OK, now

I’m going to jump up in the air and do three somersaults, and I’m going

to land, and I’m going to stretch my hands out, and I’m going to make this

beautiful formation at the end of it.” You can’t do that. It

has to be natural, like catching a ball. Smedvig: Right.

Smedvig: Right. Rafael Méndez (March 26, 1906 – September 15, 1981)

was a Mexican virtuoso solo trumpeter. He is known as the "Heifetz

of the Trumpet."

Rafael Méndez (March 26, 1906 – September 15, 1981)

was a Mexican virtuoso solo trumpeter. He is known as the "Heifetz

of the Trumpet."Méndez was born in Jiquilpan, Michoacán, Mexico to a musical family. As a child, he performed as a cornetist for guerilla leader Pancho Villa, becoming a favorite musician of his, and required to remain with Villa's camp. Méndez emigrated to the US, first settling in Gary, Indiana, at age 20 and worked in steel mills. He moved to Flint, Michigan and worked at a Buick automotive plant as he established his musical career. From 1950 to 1975, Méndez was a full-time soloist. At his peak he performed about 125 concerts per year. He was also very active as a recording artist. By 1940, he was in Hollywood, leading the brass section of M-G-M's studio orchestra. He contributed to the films Flying Down to Rio and Hondo, among others. Méndez was legendary for his tone, range, technique and unparalleled double tonguing. His playing was characterized by a brilliant tone, wide vibrato and clean, rapid articulation. His repertoire was a mixture of classical, popular, jazz, and Mexican folk music. He contributed many arrangements and original compositions to the trumpet repertoire. His Scherzo in D minor is often heard in recitals. He is regarded as popularizing "La Virgen de la Macarena", commonly known to US audiences as "the bullfighter's song." Perhaps his most significant if not famous single recording, "Moto Perpetuo", was written in the eighteenth century by Niccolò Paganini for violin, and features Mendez double-tonguing continuously for over 4 minutes while circular breathing to give the illusion that he is not taking a natural breath while playing. Méndez married Amor Rodriguez after meeting her in Detroit. They had twin sons, both surgeons, and five grandchildren. Méndez suffered from serious asthma-related problems by the

late 1950s which caused increasing difficulty performing at his level of

performance. After an injury at a baseball game in Mexico in 1967 caused

additional deterioration, he retired from performing in 1975, but

continued to compose and arrange. He died at his home in Encino, California. In 2006, the Los Angeles Opera paid tribute to Rafael Mendez by performing a work based on his life. A reviewer in The Los Angeles Times believed that Mendez "has been called the greatest trumpet player of all time." |

|

Firth was the principal timpanist of the Boston Symphony Orchestra from 1956 to 2002. He was the orchestra's youngest member when music director Charles Munch hired him as a percussionist in 1952, a distinction later held by Smedvig! Firth wrote several books including The Solo Timpanist in 1963. He wrote for snare drum with his Snare Drum Method Book I - Elementary, and Snare Drum Method Book II - Intermediate, published in 1967 and 1968. These books combined the concepts of orchestral snare drum technique with the 26 NARD Drum rudiments of his time. He followed with the more advanced book The Solo Snare Drummer in 1968.Founded in 1963 and headquartered in Boston, Massachusetts, the Vic Firth Company billed itself as the world's largest manufacturer of drumsticks and mallets, which were made in Newport, Maine. In 2010, the company merged with Avedis Zildjian Company, and officials said at the time that the companies would continue to run independently. The company began when Firth, who had been performing with the Boston Symphony Orchestra for 12 years, was asked to perform pieces which he felt required a higher-quality drumstick than those that were currently being manufactured. Firth decided to design a set of his own sticks. Firth hand-whittled the first sticks himself from bulkier sticks, and sent these prototypes to a wood turner in Montreal, Quebec, Canada. The two prototypes that he sent would become the SD1 and SD2, the first two models of sticks manufactured by Vic Firth, Inc. Firth said, "It came out of necessity, not of imagination or my ability to start a company." Although the sticks were initially intended for Firth's personal use, they gained popularity among his students and were eventually carried by retailers. As of 2012, the company offered about 300 products, and made 12 million sticks a year. The company also produced a line of pepper mills, salt grinders, and rolling pins sold under the Vic Firth Gourmet brand for many years until those interests were sold to Maine Wood Concepts of New Vineyard, Maine in 2012 and re-branded under the name Fletchers' Mill.

|

Smedvig: After ten years, I felt that

there were certain things that I wanted to do with my playing career

that I really could not do in the orchestra. The last three seasons

I really was too busy. I was trying to play solo concerts, I was

trying to play with the quintet, and I was playing in the orchestra. I

remember one weekend... Friday afternoon we were playing Petrouchka,

which has a big trumpet part. Then I flew to Pittsburgh that night

and played a recital. I flew back the next morning, started working

on a record, played another concert Saturday night, again Petrouchka.

Then, Sunday afternoon, I had a trumpet recital with an organ.

I remember getting in bed that night and thinking to myself that this is

ridiculous. At a certain point during the last couple of seasons,

the quintet was playing at least thirty or forty concerts a year. I

was playing at least ten solo dates a year, and there was the Boston Symphony

schedule. It was too much. So, I sat down with Seiji, and we

had a wonderful conversation. His advice was that when you’re dead

and in your grave, looking back at what you’ve done with your life, what

is going to make you the most happy? In terms of music, the most

important aspect for me is writing, composing and arranging. That’s

number one for me. Second would be playing on the trumpet, and there

are many different vehicles you can use besides solo trumpet. It’s

really a unique, odd instrument. There aren’t really many solo trumpet

players around. There are a few, but it’s difficult in the real

world to be a solo trumpet player. Being a quintet player along with

that obviously helps, as does being a trumpet player in an orchestra. [With

a frustrated look] But let’s face it, a trumpet player in the orchestra

is basically a percussion instrument. You emphasize certain points,

whether it be pianissimo or fortissimo, doesn’t really matter. You

do get an occasional lyrical solo, and I feel the music inside of me, whatever

I have to offer is, is really sound in lyrical playing. I was never

really even trained as an orchestral player.

Smedvig: After ten years, I felt that

there were certain things that I wanted to do with my playing career

that I really could not do in the orchestra. The last three seasons

I really was too busy. I was trying to play solo concerts, I was

trying to play with the quintet, and I was playing in the orchestra. I

remember one weekend... Friday afternoon we were playing Petrouchka,

which has a big trumpet part. Then I flew to Pittsburgh that night

and played a recital. I flew back the next morning, started working

on a record, played another concert Saturday night, again Petrouchka.

Then, Sunday afternoon, I had a trumpet recital with an organ.

I remember getting in bed that night and thinking to myself that this is

ridiculous. At a certain point during the last couple of seasons,

the quintet was playing at least thirty or forty concerts a year. I

was playing at least ten solo dates a year, and there was the Boston Symphony

schedule. It was too much. So, I sat down with Seiji, and we

had a wonderful conversation. His advice was that when you’re dead

and in your grave, looking back at what you’ve done with your life, what

is going to make you the most happy? In terms of music, the most

important aspect for me is writing, composing and arranging. That’s

number one for me. Second would be playing on the trumpet, and there

are many different vehicles you can use besides solo trumpet. It’s

really a unique, odd instrument. There aren’t really many solo trumpet

players around. There are a few, but it’s difficult in the real

world to be a solo trumpet player. Being a quintet player along with

that obviously helps, as does being a trumpet player in an orchestra. [With

a frustrated look] But let’s face it, a trumpet player in the orchestra

is basically a percussion instrument. You emphasize certain points,

whether it be pianissimo or fortissimo, doesn’t really matter. You

do get an occasional lyrical solo, and I feel the music inside of me, whatever

I have to offer is, is really sound in lyrical playing. I was never

really even trained as an orchestral player. BD: Do you tour with a whole slew of

instruments?

BD: Do you tour with a whole slew of

instruments?

BD: What finally made the decision for you?

BD: What finally made the decision for you?

Smedvig: This was selected by one of

the original players, Charlie Lewis. We had just all sort of

gotten together. Leonard Bernstein hired us to play the Mass,

which opened the Kennedy Center, and we all fell in love with each other.

When the Mass was finished, we just started rehearsing, and rehearsed

and rehearsed and rehearsed. Charlie Lewis, one of the other

trumpet players, was trying to figure out a name for it. He was

doing a Joe Papp production of Much Ado About Nothing at the Winter

Garden Theater in New York. We were all in New York because when

you don’t have work, like every other good musician, you go to New York.

Charlie was standing there at intermission, and he looked out the

back door of the theater, and he asked the doorman what we should we name

our group. The guy looked up, and there was the Empire State Building.

He said “Why don’t you call it the Empire Brass?” So, that was

it, for lack of a better name. Originally, we actually did think that

we were all going to be working in New York, and we’re still booked

out of New York City. Like every good musician, we have strong

ties to New York City.

Smedvig: This was selected by one of

the original players, Charlie Lewis. We had just all sort of

gotten together. Leonard Bernstein hired us to play the Mass,

which opened the Kennedy Center, and we all fell in love with each other.

When the Mass was finished, we just started rehearsing, and rehearsed

and rehearsed and rehearsed. Charlie Lewis, one of the other

trumpet players, was trying to figure out a name for it. He was

doing a Joe Papp production of Much Ado About Nothing at the Winter

Garden Theater in New York. We were all in New York because when

you don’t have work, like every other good musician, you go to New York.

Charlie was standing there at intermission, and he looked out the

back door of the theater, and he asked the doorman what we should we name

our group. The guy looked up, and there was the Empire State Building.

He said “Why don’t you call it the Empire Brass?” So, that was

it, for lack of a better name. Originally, we actually did think that

we were all going to be working in New York, and we’re still booked

out of New York City. Like every good musician, we have strong

ties to New York City.

© 1995 Bruce Duffie

This conversation was recorded in Chicago on February 2, 1995. Portions were broadcast on WNIB the following September, and again in 2000. This transcription was made in 2020, and posted on this website at that time. My thanks to Adam Gallant for his help in preparing this website presentation.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website, click here. To read my thoughts on editing these interviews for print, as well as a few other interesting observations, click here.

Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM, as well as on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio.

You are invited to visit his website for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.