A Conversation with Bruce Duffie

BD: In thinking about composing, is there anything

in the realm of sound that you would not want to include in a piece of your

music at some point?

BD: In thinking about composing, is there anything

in the realm of sound that you would not want to include in a piece of your

music at some point? GC: I think it’s useful to always stay in touch

with what young people are thinking. It may be that a certain fleeting

idea in a piece may reflect in something that I would be doing, but usually

the students are looking to their teachers for this same sort of thing.

So maybe it’s only fair if it can be mutual at times.

GC: I think it’s useful to always stay in touch

with what young people are thinking. It may be that a certain fleeting

idea in a piece may reflect in something that I would be doing, but usually

the students are looking to their teachers for this same sort of thing.

So maybe it’s only fair if it can be mutual at times. GC: Well, as I mentioned before, I think you’re

trying to get something out of your system. For the composer in his

workshop, it’s a question of making something come out right, and to get

out what you want to say. In fact the composer is serving as his own

audience during the process of writing music, and then once the piece is

completed, you hope that it does project to other people. But

I really don’t think that this is pervading your mind at each step of composing

a work. To me, this would be psychologically impossible. You’re

involved in the problems of the piece. I can understand the source

of the point, I suppose, if audiences are reacting against a kind of scholastic

music, academic music that perhaps is kind of cold and does not engage people

on any kind of a human plane. But otherwise, I really don’t understand

that question so much, because I think the composer, in writing a piece of

music, is functioning as a human being, primarily, and therefore he is representative,

as one person of the audience, in writing the piece.

GC: Well, as I mentioned before, I think you’re

trying to get something out of your system. For the composer in his

workshop, it’s a question of making something come out right, and to get

out what you want to say. In fact the composer is serving as his own

audience during the process of writing music, and then once the piece is

completed, you hope that it does project to other people. But

I really don’t think that this is pervading your mind at each step of composing

a work. To me, this would be psychologically impossible. You’re

involved in the problems of the piece. I can understand the source

of the point, I suppose, if audiences are reacting against a kind of scholastic

music, academic music that perhaps is kind of cold and does not engage people

on any kind of a human plane. But otherwise, I really don’t understand

that question so much, because I think the composer, in writing a piece of

music, is functioning as a human being, primarily, and therefore he is representative,

as one person of the audience, in writing the piece. BD: Where does Ross Lee Finney fit into that?

BD: Where does Ross Lee Finney fit into that? BD: What about the recordings? Many of your

works have been recorded; are you basically pleased with these?

BD: What about the recordings? Many of your

works have been recorded; are you basically pleased with these?  GC: At least it’s recognition by whoever happened

to be on the panel that awarded you that prize!

GC: At least it’s recognition by whoever happened

to be on the panel that awarded you that prize!  GC: It’s work! It’s fun when you are finishing

a piece and you say you’re relatively happy with it; it’s come together.

But starting a new work I wouldn’t describe quite as fun. It’s kind

of a searching process. I’m more impressed with the kind of work aspect

of it! But isn’t that true of everything in life, that fun is relative?

Maybe fun is not the right word. I suppose it’s kind of a thralldom.

GC: It’s work! It’s fun when you are finishing

a piece and you say you’re relatively happy with it; it’s come together.

But starting a new work I wouldn’t describe quite as fun. It’s kind

of a searching process. I’m more impressed with the kind of work aspect

of it! But isn’t that true of everything in life, that fun is relative?

Maybe fun is not the right word. I suppose it’s kind of a thralldom. GC: Well, I haven’t thought about that. I

guess to a performer I would say — extrapolating from what I tell my composition

students — is that you should have enough technique to realize your ideas,

but then the essential thing is something beyond technique. I think

that holds for performance just as much as for the conceptual thing in composition.

I mention that only because sometimes you do hear performances that are technically

astounding, but maybe a little cold and lacking in kind of that human thing.

So the ideal would be a combination of the two. Technique is important,

too. Now as regards contemporary music, I think that performers should

maybe realize that when they are able to play new music well; this lends

something to even their performance of traditional music. It sharpens

the ear; it sharpens their technique; it enlarges the possibilities.

So in playing any new work really well, I think you would play Beethoven

better. It enlarges your sound sense and I think it enlarges your imaginative

powers that befit the special instrument you’re involved with.

GC: Well, I haven’t thought about that. I

guess to a performer I would say — extrapolating from what I tell my composition

students — is that you should have enough technique to realize your ideas,

but then the essential thing is something beyond technique. I think

that holds for performance just as much as for the conceptual thing in composition.

I mention that only because sometimes you do hear performances that are technically

astounding, but maybe a little cold and lacking in kind of that human thing.

So the ideal would be a combination of the two. Technique is important,

too. Now as regards contemporary music, I think that performers should

maybe realize that when they are able to play new music well; this lends

something to even their performance of traditional music. It sharpens

the ear; it sharpens their technique; it enlarges the possibilities.

So in playing any new work really well, I think you would play Beethoven

better. It enlarges your sound sense and I think it enlarges your imaginative

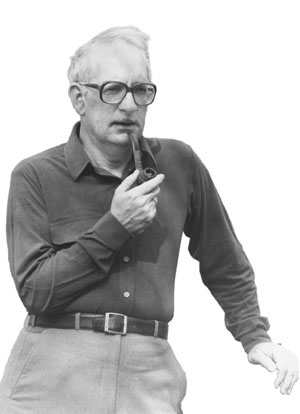

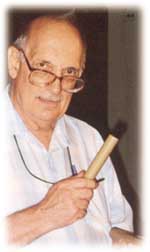

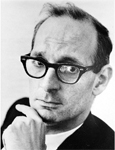

powers that befit the special instrument you’re involved with.George Crumb's reputation as a composer of hauntingly beautiful scores has made him one of the most frequently performed composers in today's musical world. From Los Angeles to Moscow, and from Scandinavia to South America, festivals devoted to the music of George Crumb have sprung up like wildflowers. Now approaching his 75th birthday year, Crumb, the winner of a 2001 Grammy Award and the 1968 Pulitzer Prize in Music, continues to compose new scores that enrich the musical lives of those who come in contact with his profoundly humanistic art.  George Henry Crumb was born in Charleston, West Virginia on 24 October 1929.

He studied at the Mason College of Music in Charleston and received the Bachelor's

degree in 1950. Thereafter he studied for the Master's degree at the University

of Illinois, Champaign-Urbana under Eugene Weigel. He continued his studies

under Boris Blacher at the Hochschule für Musik, Berlin from 1954-1955.

He received the D.M.A. in 1959 from the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor

after studying with Ross Lee Finney.

George Henry Crumb was born in Charleston, West Virginia on 24 October 1929.

He studied at the Mason College of Music in Charleston and received the Bachelor's

degree in 1950. Thereafter he studied for the Master's degree at the University

of Illinois, Champaign-Urbana under Eugene Weigel. He continued his studies

under Boris Blacher at the Hochschule für Musik, Berlin from 1954-1955.

He received the D.M.A. in 1959 from the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor

after studying with Ross Lee Finney.George Crumb's music often juxtaposes contrasting musical styles. The references range from music of the western art-music tradition, to hymns and folk music, to non-Western musics. Many of Crumb's works include programmatic, symbolic, mystical and theatrical elements, which are often reflected in his beautiful and meticulously notated scores. A shy, yet warmly eloquent personality, Crumb retired from his teaching position at the University of Pennsylvania after more than 30 years of service. Awarded honorary doctorates by numerous universities and the recipient of dozens of awards and prizes, Crumb makes his home in Pennsylvania, in the same house where he and his wife of more than 50 years raised their three children. George Crumb's music is published by C.F. Peters and the ongoing series of "Complete Crumb" recordings, supervised by the composer, is being issued on Bridge Records. George Crumb is the recipient of numerous awards: * Elizabeth Croft fellowship for study, Berkshire Music Centre, 1955. * Fulbright Scholarship, 1955-6. * BMI student award, 1956. * Rockefeller grant, 1964. * National Institute of Arts and Letters grant, 1967. * Guggenheim grant, 1967, 1973. * Pulitzer Prize (for Echoes of Time and the River), 1968. * UNESCO International Rostrum of Composers Award, 1971. * Koussevitzky Recording Award, 1971. * Fromm grant, 1973. * Member, National Institute of Arts and Letters, 1975. * Ford grant, 1976. * Prince Pierre de Monaco Gold Medal, 1989. * Brandeis University Creative Arts Award. * Honorary member, Deutsche Akademie der Kunste. * Honorary member, International Cultural Society of Korea. * 6 honorary degrees. * 1998 Cannes Classical Award: Best CD of a Living Composer (BRIDGE 9069) * 2001 Grammy for Best Contemporary Composition (Star-Child) * 2004 Musical American "Composer of the Year" |

This interview was recorded on the telephone on August 27, 1988.

Portions (along with recordings) were broadcast on WNIB in 1989, 1994 and

1999. The transcription was made in 2008 and posted on this website

in December of that year.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website, click here. To read my thoughts on editing these interviews for print, as well as a few other interesting observations, click here.

Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM, as well as on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio.

You are invited to visit his website for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.