BD: Do you always get it right?

BD: Do you always get it right? BH: That is very difficult. Of course, there

are technical things. Men like Boulez can tell you why

Schoenberg is a great composer, and so on. I am not that versatile;

I’m not that articulate. Great art, of course, is a mystery, in a way.

Take a man like Mozart. Maybe he was a very ordinary fellow, and maybe

he was not such a nice man. Who cares? Who knows? But he

has written in his thirty-five years of life the most outrageous beautiful

works! What is that? He wasn’t such a great man. He was

a tiny little man who loved filthy jokes and loved to gamble and lost lots

of money and was very tricky to people. But he was just that incredible

genius! And he must have had, also, somewhere, a very warm, human touch.

You see this when you read his letters, his caring letters for his wife

and to his father. That’s a human being! Also consider a controversial

figure like Richard Wagner — my goodness! We all have our moments,

but what makes it that these people, who can be horrible in life to other

people, how is it possible that these people can create such masterpieces?

That is the secret of genius. And one must have enormous respect.

I think that’s sort of mystery, why that happens. Let’s be happy.

I am happy that they come and reveal the mystery. I’m happy that I

can’t give you an answer to the question of what makes a good piece.

I can’t.

BH: That is very difficult. Of course, there

are technical things. Men like Boulez can tell you why

Schoenberg is a great composer, and so on. I am not that versatile;

I’m not that articulate. Great art, of course, is a mystery, in a way.

Take a man like Mozart. Maybe he was a very ordinary fellow, and maybe

he was not such a nice man. Who cares? Who knows? But he

has written in his thirty-five years of life the most outrageous beautiful

works! What is that? He wasn’t such a great man. He was

a tiny little man who loved filthy jokes and loved to gamble and lost lots

of money and was very tricky to people. But he was just that incredible

genius! And he must have had, also, somewhere, a very warm, human touch.

You see this when you read his letters, his caring letters for his wife

and to his father. That’s a human being! Also consider a controversial

figure like Richard Wagner — my goodness! We all have our moments,

but what makes it that these people, who can be horrible in life to other

people, how is it possible that these people can create such masterpieces?

That is the secret of genius. And one must have enormous respect.

I think that’s sort of mystery, why that happens. Let’s be happy.

I am happy that they come and reveal the mystery. I’m happy that I

can’t give you an answer to the question of what makes a good piece.

I can’t. BD: Aside from the very obvious, what are the basic

differences between conducting an opera performance and conducting a concert

symphonic performance?

BD: Aside from the very obvious, what are the basic

differences between conducting an opera performance and conducting a concert

symphonic performance? BD: Do you leave enough time in your life for study

and preparation?

BD: Do you leave enough time in your life for study

and preparation? BH: Oh, my goodness! I love to work with

younger conductors. I have done that several times at Tanglewood.

I can’t give an overall advice because every talent is different. My

attitude is that I’m not going to say he has more talent than he. It’s

not a competition here.” I look at them; I let them do things and listen

to them, and then I try, in their possibilities or in their impossibilities,

to change things or to give them some advice. Sometimes it’s very simple.

Some batons fiddle around. Then I ask, “What do you mean with that?

Do you think that helps? I am now an orchestra musician, so give me

a beat that I can play on; but not only give a beat correctly, but also in

the right mood, the right sound. And why is your left hand so contrived?

Let go, and maybe you get a more relaxed sound.” So, everyone has a

different problem or a different asset, and I find it fascinating to bring

that out and make it conscious to them. Last summer I had also two

fellow students with the Tanglewood Music Center Orchestra (the young people).

I had to observe them and coach them diplomatically. I had a concert

with them; I did two pieces and they did two pieces. One did the Manfred

Overture the other one did a Haydn Symphony. It was very interesting,

a total difference in their characters. In that situation I changed

seats. First I was in the hall, and then I was in the orchestra.

They have fifty minutes in the morning and another fifty minutes in the afternoon.

So there you are in front of musicians, and every word you say can be very

hurtful for these conductors; you have to be very careful. You should

not destroy them, you should stimulate them. So I let him go on for

ten minutes and then I said, “Do you really think that works? Why

don’t you try it another way to see if it is good for you, if it suits your

hands, and if you get the sound and the tempo you want.” Everyone is

different.

BH: Oh, my goodness! I love to work with

younger conductors. I have done that several times at Tanglewood.

I can’t give an overall advice because every talent is different. My

attitude is that I’m not going to say he has more talent than he. It’s

not a competition here.” I look at them; I let them do things and listen

to them, and then I try, in their possibilities or in their impossibilities,

to change things or to give them some advice. Sometimes it’s very simple.

Some batons fiddle around. Then I ask, “What do you mean with that?

Do you think that helps? I am now an orchestra musician, so give me

a beat that I can play on; but not only give a beat correctly, but also in

the right mood, the right sound. And why is your left hand so contrived?

Let go, and maybe you get a more relaxed sound.” So, everyone has a

different problem or a different asset, and I find it fascinating to bring

that out and make it conscious to them. Last summer I had also two

fellow students with the Tanglewood Music Center Orchestra (the young people).

I had to observe them and coach them diplomatically. I had a concert

with them; I did two pieces and they did two pieces. One did the Manfred

Overture the other one did a Haydn Symphony. It was very interesting,

a total difference in their characters. In that situation I changed

seats. First I was in the hall, and then I was in the orchestra.

They have fifty minutes in the morning and another fifty minutes in the afternoon.

So there you are in front of musicians, and every word you say can be very

hurtful for these conductors; you have to be very careful. You should

not destroy them, you should stimulate them. So I let him go on for

ten minutes and then I said, “Do you really think that works? Why

don’t you try it another way to see if it is good for you, if it suits your

hands, and if you get the sound and the tempo you want.” Everyone is

different. BH: Yeah, yeah, yeah, but I wanted to be a conductor

and I got my way into these conductor’s courses. I had the luck that

the conductor, the teacher, was extremely helpful for me. He died recently,

Ferdinand Leitner.

After the second Conductor’s Course, he said, “Either you go with me in Stuttgart,”

because he was music director there, “or you will get a job with Dutch Radio.

I will do that for you.” And it happened that I got the job at the

Dutch Radio. So I had enormous luck; I was helped enormously!

BH: Yeah, yeah, yeah, but I wanted to be a conductor

and I got my way into these conductor’s courses. I had the luck that

the conductor, the teacher, was extremely helpful for me. He died recently,

Ferdinand Leitner.

After the second Conductor’s Course, he said, “Either you go with me in Stuttgart,”

because he was music director there, “or you will get a job with Dutch Radio.

I will do that for you.” And it happened that I got the job at the

Dutch Radio. So I had enormous luck; I was helped enormously! BH: That’s a very difficult question. I don’t

know. The best comparison may be, speaking for myself, I never like

to hear my own voice on tape and I know that other people also have that problem.

And it takes a very, very long time before I really have the peace of mind

to listen to my own recordings. I never do that immediately. Of

course I listen during the sessions, I listen to the takes, but that’s a

different thing! Then you are in that whole working process. But

once the last session is finished, I let it go. Of course, you get

the trial recording where you have to approve, or you have to give them your

opinions, and I try do it; strange enough, not too seriously! I will

then never listen with the score; I just think, “Now I want to listen totally

casually and see how it comes my way.” So I very seldom hear technical

details. I know artists who send the list back of a hundred and twenty

points they have! That I don’t do.

BH: That’s a very difficult question. I don’t

know. The best comparison may be, speaking for myself, I never like

to hear my own voice on tape and I know that other people also have that problem.

And it takes a very, very long time before I really have the peace of mind

to listen to my own recordings. I never do that immediately. Of

course I listen during the sessions, I listen to the takes, but that’s a

different thing! Then you are in that whole working process. But

once the last session is finished, I let it go. Of course, you get

the trial recording where you have to approve, or you have to give them your

opinions, and I try do it; strange enough, not too seriously! I will

then never listen with the score; I just think, “Now I want to listen totally

casually and see how it comes my way.” So I very seldom hear technical

details. I know artists who send the list back of a hundred and twenty

points they have! That I don’t do. BH: For me it’s very serious business. Maybe,

because I’m basically very serious, and basically also sometimes quite pessimistic,

therefore sometimes maybe I lose out on the fun side of it. It gives

me enormous pleasure, but you never get used to it. The last minutes

before a performance, no matter how often you have done it, you’re always

looking into the abyss. That’s my experience. Of course, when

the thing goes well there is an enormous feeling of satisfaction afterwards,

and I should not underplay that. When I say look into the abyss, it’s

a thing you never get used to. I don’t know any artist who doesn’t,

more or less, tremble before a performance.

BH: For me it’s very serious business. Maybe,

because I’m basically very serious, and basically also sometimes quite pessimistic,

therefore sometimes maybe I lose out on the fun side of it. It gives

me enormous pleasure, but you never get used to it. The last minutes

before a performance, no matter how often you have done it, you’re always

looking into the abyss. That’s my experience. Of course, when

the thing goes well there is an enormous feeling of satisfaction afterwards,

and I should not underplay that. When I say look into the abyss, it’s

a thing you never get used to. I don’t know any artist who doesn’t,

more or less, tremble before a performance. |

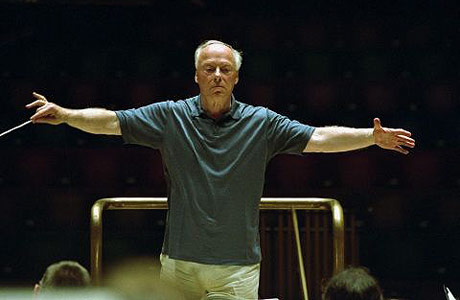

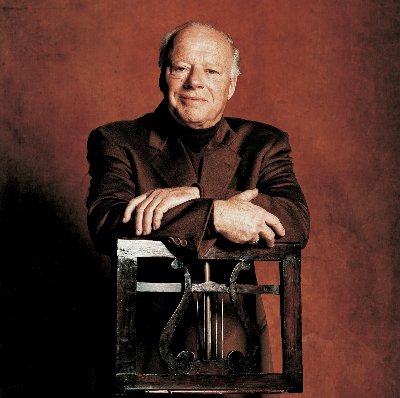

Bernard Haitink

With an international conducting career that has spanned more than five decades, Amsterdam-born Bernard Haitink is one of today's most celebrated conductors. Principal Conductor of the Chicago Symphony Orchestra since 2006, he was for more than 25 years at the helm of the Royal Concertgebouw as its music director. In addition, Mr Haitink has previously held posts as music director of the Dresden Staatskapelle, the Royal Opera, Covent Garden, Glyndebourne Festival Opera, and the London Philharmonic. He is Conductor Laureate of the Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra and Conductor Emeritus of the Boston Symphony Orchestra. He has made frequent guest appearances with most of the world’s leading orchestras. The 2008-9 season includes tours to Europe, Japan, Hong Kong and China with the Chicago Symphony Orchestra, as well as performances in Chicago and Carnegie Hall, New York. He will complete the cycle of Beethoven symphonies, concertos and overtures with the Chamber Orchestra of Europe started in Easter 2008 at the Summer 2008 and Easter 2009 Luzern Festivals. Other highlights of the season include a new production of “Fidelio” at the Zürich Opera, and concerts with the Berlin Philharmonic and London Symphony Orchestras. He celebrates his 80th birthday in March 2009 with concerts with the Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra in Amsterdam and at The Barbican Centre, London. Mr Haitink has recorded widely for Phillips, Decca and EMI labels, including complete cycles of Mahler, Bruckner, and Schumann symphonies with the Concertgebouw and extensive repertoire with the Berlin and Vienna Philharmonic orchestras and the Boston Symphony Orchestra. His most recent recordings are the complete Brahms and Beethoven symphonies with the London Symphony Orchestra on the LSO Live label, and Mahler’s Symphonies no.3 and 6 and Bruckner Symphony no.7 with the Chicago Symphony for their new “Resound” label. His discography also includes many opera recordings with the Royal Opera and Glyndebourne, as well as with the Bavarian Radio Orchestra and Dresden Staatskapelle. Mr Haitink’s recording of Janacek’s Jenufa with the orchestra, soloists, and chorus of the Royal Opera House, Covent Garden received a Grammy Award for best opera recording in 2004. Mr Haitink has received many international awards in recognition of his services to music, including both an honorary Knighthood and the Companion of Honour in the United Kingdom, and the House Order of Orange-Nassau in the Netherlands. He was named Musical America’s “Musician of the Year” for 2007. |

This interview was recorded at Orchestra Hall in Chicago on January

13, 1997. Portions (along with recordings) were broadcast on WNIB in

1999, and on WNUR in 2003. The transcription was made in 2008 and posted

on this website in December of that year.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website, click here. To read my thoughts on editing these interviews for print, as well as a few other interesting observations, click here.

Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM, as well as on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio.

You are invited to visit his website for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.