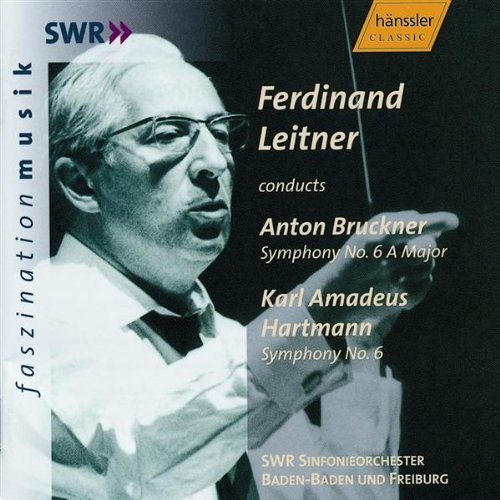

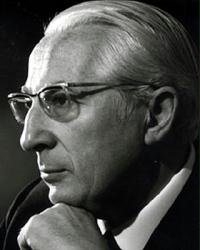

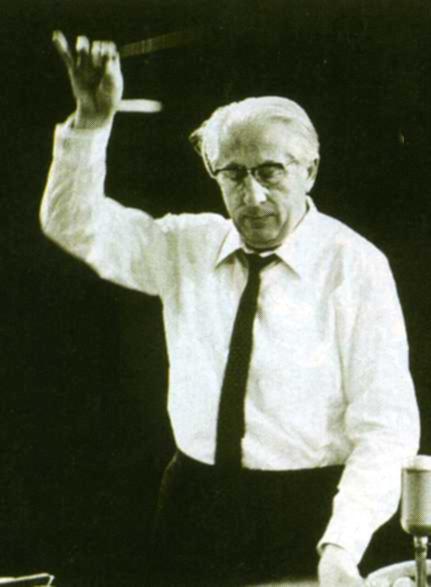

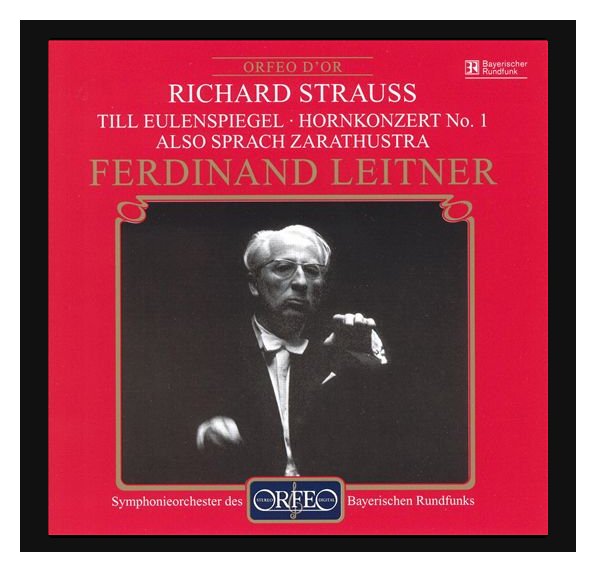

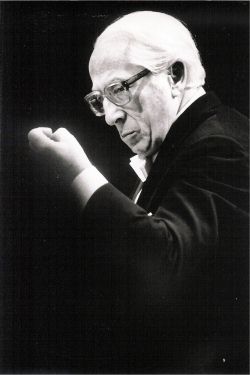

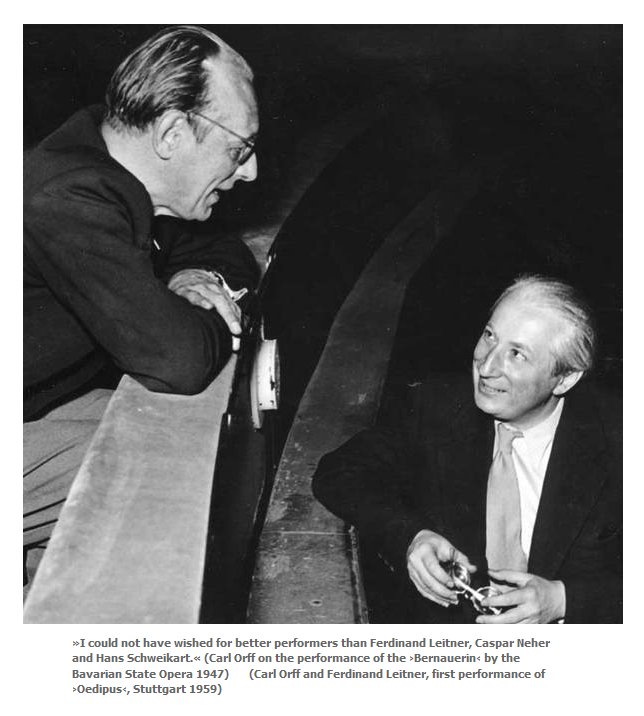

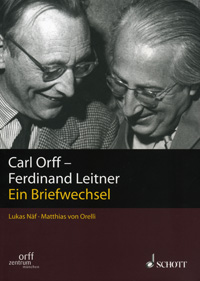

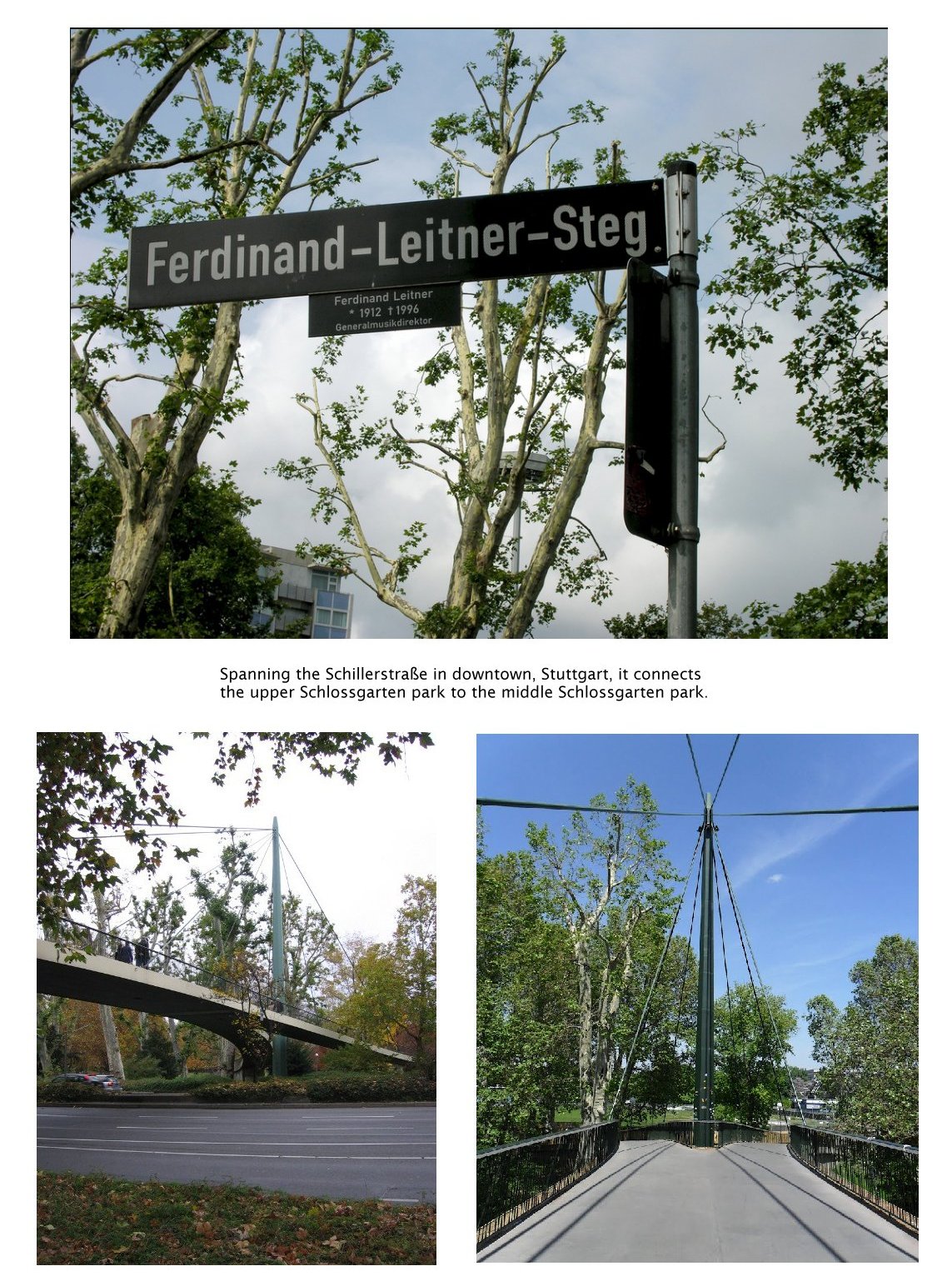

| Ferdinand Leitner (Conductor) Born: March 4, 1912 - Berlin, Germany Died: June 1996 - Forch (Zürich), Switzerland The noted German conductor, Ferdinand Leitner, studied at the Music School in his home city under Fritz Schreker and Julius Prüwer from 1926 to 1931, as well as receiving instruction from Artur Schnabel and Karl Muck. After completing his studies, Ferdinand Leitner began appearing as a pianist, particularly as accompanist to Georg Kulenkampff and Ludwig Hoelscher. He made his debut in Berlin as conductor during this period. In 1935, Fritz Busch engaged him as assistant at Glyndebourne. From 1943 to 1945, he was director of music at the Theatre on the Nollendorfplatz in Berlin, and from 1945 to 1946 in Hannover, from 1946 to 1947 in Munich, from 1947 in Stuttgart, always in the same function. He became chief musical director in Stuttgart in 1949 and served there until 1969. From 1947 to 1951, he was senior musical director of the Bach Weeks in Ansbach. Ferdinand Leitner conducted the rehearsals for the first performance of Igor Igor Stravinsky's The Rake's Progress in Venice in 1951, the performance itself being conducted by the composer personally. Composer and conductor then alternated. He succeeded Erich Kleiber as conductor of the German operas at the Teatro Colón in Buenos Aires in 1956. From 1969 to 1984, he was senior musical director of the Zürich Opera and from 1976 to 1980 principal conductor of the Residence Orchestra in The Hague at the same time. From 1988, he was principal guest conductor of the RAI Symphony Orchestra in Turin. Ferdinand Leitner became known mainly as an opera conductor. He promoted 20th-century German opera, especially the works of Carl Orff and Karl Amadeus Hartmann. He also promoted the works of Ferruccio Busoni. His premieres include the operas Oedipus the King by Carl Orff (1959), Don Juan und Faust (1950) as well as Hamlet (1980), both by Hermannn Reutter. |

BD: I wonder what their problem is with Schumann?

BD: I wonder what their problem is with Schumann?| [From an article on Die Soldaten] Even today a stage performance of Die Soldaten places very great demands on any opera company. In addition to the sixteen singing and ten speaking roles, it requires a one hundred-piece orchestra involving many unusual instruments and pieces of percussion. With its open action, a large amount of scenes which at times overlap one another or run simultaneously (the second scene of act 2, for example, or all of act 4), its multimedia structure incorporating film screens, projectors, tape recordings and loudspeakers, in addition to the sound effects of marching, engines and screams, Die Soldaten –an opera composed using the strict rules of twelve-tone music and presenting a high degree of complexity despite its careful design for the stage– is a uniquely complicated opera, both to stage and to watch. There are numerous unorthodox roles in this opera, but the most noticeable is the mass usage of banging chairs and tables on the stage floor as percussion instruments. This is carried out by many of the actors with non-singing roles. The composer also calls for 3 cinema screens, 3 film projectors & groups of loudspeakers on the stage and in the auditorium. The orchestra is composed of: 4 flutes (all 4 doubling on piccolos, flute 3 also doubling on alto flute in G), 3 oboes (doubling also on oboe d'amore, oboe 3 also doubling on cor anglais), 4 clarinets in B-flat (1, 3 & 4 also in A, clarinet 3 also bass clarinet, clarinet 4 also on E-flat clarinet), alto saxophone in E-flat, 3 bassoons (2 & 3 also contrabassoon), 5 horns in F (all 5 also tenor tuba in B-flat, Horn 5 also bass tuba in F), 4 trumpets in C (1 & 2 also trumpets in B-flat & F; 3 & 4 also in B-flat & A and bass trumpet in E-flat), 4 trombones (Trombone 4 contrabass trombone), bass tuba (also contrabass tuba), timpani (also small timpani), percussion (8-9 players), 3 crotales (E-flat, F & G), 3 crotals (high, medium & low), gegenschlagblock (counterstroke block), 3 cymbals, 4 gongs, 4 tamtams, tambourine, 3 bongos, 5 tomtoms, tumba, military drum, 4 small drums, friction drum, 2 large drums (one of them horizontal), 5 triangle (instrument), cow bells, steel sticks, 2 sets of tubular bells, 3 free-running railway rails, whip (instrument), castanets, rumbaholz, 2 wood covers, 3 wood drums, güiro, maracas, vibration pipe, xylophone, marimba, vibraphone, guitar, 2 harps, glockenspiel, celesta, harpsichord, piano, organ (2 players) & strings. On the stage (6 players): I. 3 triangles (high register), 3 crotals (high), 2 basins (high), gong (small), tamtam (small), small drum, military drum, 2 bongos, agitating drum, large drum (with cymbals), 3 bass drums, cow bell (high), 2 tube bells, maracas & temple block (high). II. 3 triangles (middle register), 3 crotals (middle), 2 basins (middle), 2 gongs (medium & large), small drum, 2 Tomtoms, agitating drum, 3 bass drums, cow bell, 6 tube bells, maracas & temple block (middle). III. 3 triangles (deep register), crotal (deep), 2 basins (deep), gong (large), 2 tamtams (small & large), small drum, tomtom (deep), snare drum, 3 bass drums, cow bell (deep), 4 tube bells, maracas, 3 temple blocks (deep); jazz band: clarinet in B-flat, trumpet in B-flat & double bass (electrically amplified). |

FL: In Stuttgart, where I was over twenty years,

it was very much to do all the things with money and with engagements and

so on. Not so in Zurich. When I was coming there, I said, “I

don’t like to sit from morning to evening in an office.” There they

ask me to do more, but they do many more things. I don’t know how much

a singer might get for a performance, but if I am interested they might say,

“No, it’s not possible because they are too expensive.” Now I do not

have to deal with that. But you first asked about the future of opera.

When I was a boy of fourteen, they asked me what I would like to do, and

I said, “I would like to be director of opera house.” They said to

me, “My boy, this is the end. Opera is finished now. You are

at an age where it is too late.”

FL: In Stuttgart, where I was over twenty years,

it was very much to do all the things with money and with engagements and

so on. Not so in Zurich. When I was coming there, I said, “I

don’t like to sit from morning to evening in an office.” There they

ask me to do more, but they do many more things. I don’t know how much

a singer might get for a performance, but if I am interested they might say,

“No, it’s not possible because they are too expensive.” Now I do not

have to deal with that. But you first asked about the future of opera.

When I was a boy of fourteen, they asked me what I would like to do, and

I said, “I would like to be director of opera house.” They said to

me, “My boy, this is the end. Opera is finished now. You are

at an age where it is too late.”  BD: Seventy full Rings?

BD: Seventy full Rings? FL: No. He didn’t like cuts there. He

said to me, “One time in my life, I’d like to hear the third act without

cuts.” I never in my life conduct without cuts because the singers

don’t know it.

FL: No. He didn’t like cuts there. He

said to me, “One time in my life, I’d like to hear the third act without

cuts.” I never in my life conduct without cuts because the singers

don’t know it. BD: So when you do Tannhäuser, which version do you

do — or do you put the two together?

BD: So when you do Tannhäuser, which version do you

do — or do you put the two together? FL: [Smiles, as he reminisces about many diverse

aspects of his friendship] This is such a special thing. I have

conducted all the stage works that he has written. I think there are

twelve. The friendship began in ’43 and ended with his death [March

29, 1982]. He was very charming in our last conversation on the telephone

a short time before he died. He was very clever, and what we call ‘wach’ (awake), but toward the end he

didn’t remember things so well. He called me twice many days, mornings

and evenings, because he had forgotten that he called me in the morning.

But in the evening he was very normal. He would ask, “Oh, this morning

I telephoned?” and I would say yes because he didn’t know. But this

was one of the greatest men in our century. First with the Schulwerk... you know there is the Orff

Institute in Salzburg, and many, many schools in the world including here

in the States learn this. I found the children are better if they learn

of Schulwerk when they make music.

They may not be musicians later, but if they must do things with their hands

and with feet, from nursery at three years, they start with this. I

found the enormous advantage to this. Maybe ten years or twelve years

ago, Orff was invited to Tokyo. When he arrived, he said to his wife,

“I’m sure there is a political man on our plane. Look here at the red

carpet,” but this was for him! He came out and

ten thousand children were singing and playing instruments for him when he

was coming down from the plane. He told me, “I never had so exact,

so fantastic a performance dozens of different conductors.” He said

it was fantastic. It was the greatest thing in his life. I have

the original manuscript of his first lied.

He knows that I am a collector of such things. I have that manuscript

and many other manuscripts from him. Back then he was feeling it’s

not possible to be a composer like Strauss and a little bit Wagner.

This was when he was nineteen, twenty, twenty-one years old, so he started

with a new style with Der Mond.

This is a fantastic thing. This may be possible to do in English, like

Die Kluge. These are stories

for the world, not only for Bavarians. They speak in original Bavarian

dialogue, but it is possible for others to share the feeling of what he wrote.

This can happen with the three things, Mond,

Kluge and Bernauerin. These are the three

Bavarian things, and they are possible to be done in English.

FL: [Smiles, as he reminisces about many diverse

aspects of his friendship] This is such a special thing. I have

conducted all the stage works that he has written. I think there are

twelve. The friendship began in ’43 and ended with his death [March

29, 1982]. He was very charming in our last conversation on the telephone

a short time before he died. He was very clever, and what we call ‘wach’ (awake), but toward the end he

didn’t remember things so well. He called me twice many days, mornings

and evenings, because he had forgotten that he called me in the morning.

But in the evening he was very normal. He would ask, “Oh, this morning

I telephoned?” and I would say yes because he didn’t know. But this

was one of the greatest men in our century. First with the Schulwerk... you know there is the Orff

Institute in Salzburg, and many, many schools in the world including here

in the States learn this. I found the children are better if they learn

of Schulwerk when they make music.

They may not be musicians later, but if they must do things with their hands

and with feet, from nursery at three years, they start with this. I

found the enormous advantage to this. Maybe ten years or twelve years

ago, Orff was invited to Tokyo. When he arrived, he said to his wife,

“I’m sure there is a political man on our plane. Look here at the red

carpet,” but this was for him! He came out and

ten thousand children were singing and playing instruments for him when he

was coming down from the plane. He told me, “I never had so exact,

so fantastic a performance dozens of different conductors.” He said

it was fantastic. It was the greatest thing in his life. I have

the original manuscript of his first lied.

He knows that I am a collector of such things. I have that manuscript

and many other manuscripts from him. Back then he was feeling it’s

not possible to be a composer like Strauss and a little bit Wagner.

This was when he was nineteen, twenty, twenty-one years old, so he started

with a new style with Der Mond.

This is a fantastic thing. This may be possible to do in English, like

Die Kluge. These are stories

for the world, not only for Bavarians. They speak in original Bavarian

dialogue, but it is possible for others to share the feeling of what he wrote.

This can happen with the three things, Mond,

Kluge and Bernauerin. These are the three

Bavarian things, and they are possible to be done in English. BD: You have also recorded many of these works.

BD: You have also recorded many of these works. BD: So they can overcome what they lack and still

perform the heavy roles?

BD: So they can overcome what they lack and still

perform the heavy roles?

This interview was recorded at his hotel in Chicago on September

24, 1982. Portions were transcribed and published in Wagner News in January, 1983. Portions

were also used (with recordings) on WNIB in 1987, 1992, 1993, 1995, and 1997.

A fresh transcript was made, and it was posted on this website in 2013.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website, click here.

Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM.

You are invited to visit his website for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.