BD: You’ve been involved in

recordings for quite a long time, and recording techniques have changed

and improved considerably. When you’re preparing a chorus or an

orchestra specifically for a recording, do the new techniques affect

the way you prepare it, or do you just let the technicians worry about

the technical stuff?

BD: You’ve been involved in

recordings for quite a long time, and recording techniques have changed

and improved considerably. When you’re preparing a chorus or an

orchestra specifically for a recording, do the new techniques affect

the way you prepare it, or do you just let the technicians worry about

the technical stuff? RS: I think generally, though

again it’d be only fair to say I’ve heard fragments. That I can

recall, I’ve never heard any record we’ve made. The reviews are

better than anything we used to get when we were winning Grammys, but I

never listen to any of those. Other than at the final splicing

sessions, I never listened to any of those old recordings or those with

the professional chorale, either. I happened to hear some in

traveling in France this summer, because somebody brought me a tape of

a bunch of old, old titles that we’d done many years ago. Things

like Whiffenpoof Song and the

B-minor Mass — a

mélange of things that Victor put out in one of its commercial

nightmares. It was charming and lots of fun, but it’d been the

first time, I suppose, in twenty to thirty years that I’d heard

anything that we’d made. We also tape our concerts for broadcast

in Atlanta, and other than for our own private study when I’ve had

somebody take something off the air for the archives so I can have it

to refer back to, I’ve never happened to hear one of those broadcasts,

either.

RS: I think generally, though

again it’d be only fair to say I’ve heard fragments. That I can

recall, I’ve never heard any record we’ve made. The reviews are

better than anything we used to get when we were winning Grammys, but I

never listen to any of those. Other than at the final splicing

sessions, I never listened to any of those old recordings or those with

the professional chorale, either. I happened to hear some in

traveling in France this summer, because somebody brought me a tape of

a bunch of old, old titles that we’d done many years ago. Things

like Whiffenpoof Song and the

B-minor Mass — a

mélange of things that Victor put out in one of its commercial

nightmares. It was charming and lots of fun, but it’d been the

first time, I suppose, in twenty to thirty years that I’d heard

anything that we’d made. We also tape our concerts for broadcast

in Atlanta, and other than for our own private study when I’ve had

somebody take something off the air for the archives so I can have it

to refer back to, I’ve never happened to hear one of those broadcasts,

either.

RS: We can talk about two things

— composition and performance. My present listening

to recordings leaves no doubt that England — in the last two decades or

certainly since World War II — is having a remarkable resurgence of

musicological research and performance standards in the choral

art. There are fine choruses in England. They always had an

extraordinary tradition of the festival-type choruses, of the

Mendelssohnian 300- and 400-voice choruses that substantially swamped

most of baroque music for almost centuries. But most recently

they’ve been doing significant musicological research which has allowed

them to bring together small choirs of very expert singers who do

really very, very beautiful work. In general, I think that the

high school and college level of performance in the United States has

been remarkable. Following World War Two, the education of choral

conductors at the University level in the United States reached a

degree of strenuousness and of intellectual distinction which really

passed the preparation of instrumental and orchestral conductors.

Orchestral conductors were still developed in the operatic schooling

grounds and so on, but the degrees offered in choral conducting at our

major universities and in the major conservatories embraced orchestral

conducting and embraced a musicological approach. It was so

necessary because there’d been a good five to six hundred years of

choral music to rediscover. Even Hindemith, whose real concern at

Yale was the development of compositional students following the war,

had his programs of performance. It was largely his group’s

seminars in the choral literature through which he approached his

compositional students. Anyway, I think the performance level is

generally extraordinarily high. There now has grown up a

completely new group of American composers with

whom I have less personal contact than I used to have and still

have. William Schuman, Aaron Copland, Sam Barber and the others

of that generation, some of whom are gone now. [See my Interview with William

Schuman.] With the Atlanta Symphony, we’re undertaking now a

series of commissions, and I suppose fifteen to twenty-five percent of

those commissions will be in the choral-symphonic field. We have

Gian Carlo Menotti and others who are writing works in the

choral-symphonic area for us. [See my Interviews with Gian

Carlo Menotti.] Bill Schuman’s doing one which we

commissioned along with the New York Philharmonic and a couple of other

orchestras. So some of that repertoire is forthcoming if it’s not

with us now, and other people are doing serious commissioning projects,

too. I don’t see any real fecundity as to match, for instance,

that of a Francis Poulenc, just a couple of decades ago, with the

really considerable number of major works which he wrote for symphony

orchestra and chorus, and his a

cappella works as well. Our American composition has not

placed as much attention on the choral repertoire as it did in my

generation and the succeeding generation. That attention now is

on the straight orchestral repertoire. At the same time, I’ve

been so intimately connected with the symphonic field rather than the

choral field. I’ve been a music director of an orchestra for over

forty years now, so my principal attention has been in the instrumental

and orchestral literature rather than the choral literature. The

choral literature has been sort of ancillary, and I may not know as

much as others know in this field. But there’s a considerable

hope that this literature will expand rapidly within the next

half-generation... unless we have some sort of a terrible sociological

catastrophe.

RS: We can talk about two things

— composition and performance. My present listening

to recordings leaves no doubt that England — in the last two decades or

certainly since World War II — is having a remarkable resurgence of

musicological research and performance standards in the choral

art. There are fine choruses in England. They always had an

extraordinary tradition of the festival-type choruses, of the

Mendelssohnian 300- and 400-voice choruses that substantially swamped

most of baroque music for almost centuries. But most recently

they’ve been doing significant musicological research which has allowed

them to bring together small choirs of very expert singers who do

really very, very beautiful work. In general, I think that the

high school and college level of performance in the United States has

been remarkable. Following World War Two, the education of choral

conductors at the University level in the United States reached a

degree of strenuousness and of intellectual distinction which really

passed the preparation of instrumental and orchestral conductors.

Orchestral conductors were still developed in the operatic schooling

grounds and so on, but the degrees offered in choral conducting at our

major universities and in the major conservatories embraced orchestral

conducting and embraced a musicological approach. It was so

necessary because there’d been a good five to six hundred years of

choral music to rediscover. Even Hindemith, whose real concern at

Yale was the development of compositional students following the war,

had his programs of performance. It was largely his group’s

seminars in the choral literature through which he approached his

compositional students. Anyway, I think the performance level is

generally extraordinarily high. There now has grown up a

completely new group of American composers with

whom I have less personal contact than I used to have and still

have. William Schuman, Aaron Copland, Sam Barber and the others

of that generation, some of whom are gone now. [See my Interview with William

Schuman.] With the Atlanta Symphony, we’re undertaking now a

series of commissions, and I suppose fifteen to twenty-five percent of

those commissions will be in the choral-symphonic field. We have

Gian Carlo Menotti and others who are writing works in the

choral-symphonic area for us. [See my Interviews with Gian

Carlo Menotti.] Bill Schuman’s doing one which we

commissioned along with the New York Philharmonic and a couple of other

orchestras. So some of that repertoire is forthcoming if it’s not

with us now, and other people are doing serious commissioning projects,

too. I don’t see any real fecundity as to match, for instance,

that of a Francis Poulenc, just a couple of decades ago, with the

really considerable number of major works which he wrote for symphony

orchestra and chorus, and his a

cappella works as well. Our American composition has not

placed as much attention on the choral repertoire as it did in my

generation and the succeeding generation. That attention now is

on the straight orchestral repertoire. At the same time, I’ve

been so intimately connected with the symphonic field rather than the

choral field. I’ve been a music director of an orchestra for over

forty years now, so my principal attention has been in the instrumental

and orchestral literature rather than the choral literature. The

choral literature has been sort of ancillary, and I may not know as

much as others know in this field. But there’s a considerable

hope that this literature will expand rapidly within the next

half-generation... unless we have some sort of a terrible sociological

catastrophe.

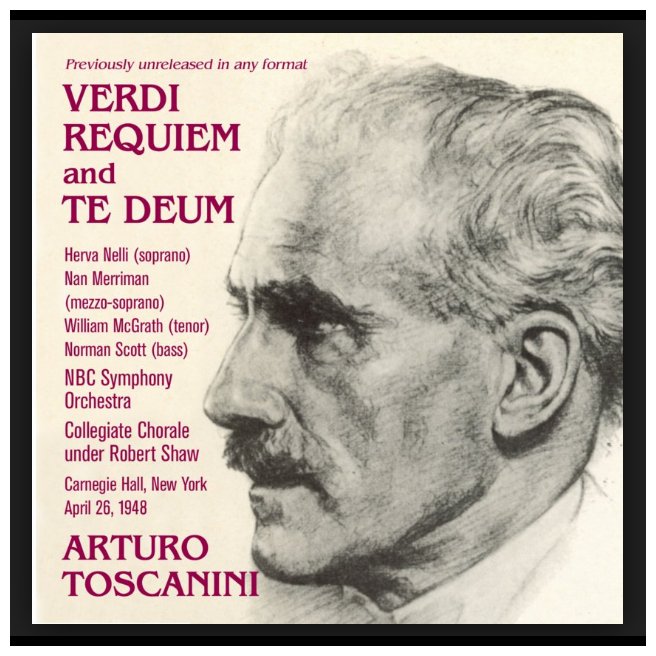

RS: It was always, for us, a

time of great joy and great happiness, and of no sweat and no

strain. All of us had heard legendary stories about his flights

of anger and such, and we witnessed one, but not at our own

expense. So it was a time of felicity and charm. There was

one memorable evening when a group of our choristers — a professional

choir which was a forerunner of our later choir that used to tour under

my name — was appearing on a performance for NBC on Christmas

Eve. I’d phoned Walter, Toscanini’s son, to ask if we might come

up to Riverdale and serenade him after the West Coast broadcast which

Guido Cantelli happened to be conducting that evening. We

rehearsed a bunch of Christmas carols which some of us had previously

recorded, and got together a little half-hour program. We went

and stood outside his door, and before we could begin singing the door

opened and Walter invited us into the house. Toscanini himself,

the maestro, was in a library off the main, large room, which had a

staircase that mounted up to the second floor. He was looking at

wrestling on television, as I remember, and we began singing. He

slowly tottered out, and we kept singing for perhaps thirty

minutes. He was just as sweet an audience as he could possibly

be. Then they opened up a room and fed us all Italian cheeses and

pastries and champagne, and he went around and spent the rest of night

talking to each of the thirty-member chorus who had come up

there. The party broke up at five to six in the morning, and he

just simply spent the night talking with people. But it was

always the most friendly when I was there working, preparing, or going

over a score with him to get his tempi and his changes of tempi, and

what he wanted in terms of dynamics and such at his home. He was

by no means a monster, but a sweet, childlike human being who couldn’t

abide people whom he felt were betraying the music. I think it’s

safe to say that his anger was purified by at least two

qualities. First, he was never sorry for himself; he was always

sorry for the composer. That was a rare quality, and the second

one was that at least in that period of his life he was

childlike. I witnessed a couple of episodes with orchestras and

such at recording sessions, and it was a tantrum which was tempestuous

and soon over. It left only a sort of a shame-faced grin on

everybody’s face when it was over, and he substantially didn’t really

remember it. He was a very pure and sweet man.

RS: It was always, for us, a

time of great joy and great happiness, and of no sweat and no

strain. All of us had heard legendary stories about his flights

of anger and such, and we witnessed one, but not at our own

expense. So it was a time of felicity and charm. There was

one memorable evening when a group of our choristers — a professional

choir which was a forerunner of our later choir that used to tour under

my name — was appearing on a performance for NBC on Christmas

Eve. I’d phoned Walter, Toscanini’s son, to ask if we might come

up to Riverdale and serenade him after the West Coast broadcast which

Guido Cantelli happened to be conducting that evening. We

rehearsed a bunch of Christmas carols which some of us had previously

recorded, and got together a little half-hour program. We went

and stood outside his door, and before we could begin singing the door

opened and Walter invited us into the house. Toscanini himself,

the maestro, was in a library off the main, large room, which had a

staircase that mounted up to the second floor. He was looking at

wrestling on television, as I remember, and we began singing. He

slowly tottered out, and we kept singing for perhaps thirty

minutes. He was just as sweet an audience as he could possibly

be. Then they opened up a room and fed us all Italian cheeses and

pastries and champagne, and he went around and spent the rest of night

talking to each of the thirty-member chorus who had come up

there. The party broke up at five to six in the morning, and he

just simply spent the night talking with people. But it was

always the most friendly when I was there working, preparing, or going

over a score with him to get his tempi and his changes of tempi, and

what he wanted in terms of dynamics and such at his home. He was

by no means a monster, but a sweet, childlike human being who couldn’t

abide people whom he felt were betraying the music. I think it’s

safe to say that his anger was purified by at least two

qualities. First, he was never sorry for himself; he was always

sorry for the composer. That was a rare quality, and the second

one was that at least in that period of his life he was

childlike. I witnessed a couple of episodes with orchestras and

such at recording sessions, and it was a tantrum which was tempestuous

and soon over. It left only a sort of a shame-faced grin on

everybody’s face when it was over, and he substantially didn’t really

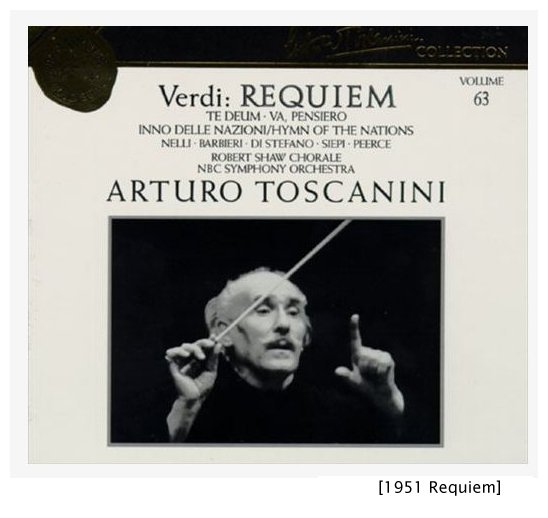

remember it. He was a very pure and sweet man. RS: No, I guess not. I

don’t happen to have a discography of my own things, though I’m looking

now in my studio and I suppose there are 115 records or so that I’ve

made, and there have to be one or two of them with Toscanini. But

we were doing this for broadcast, and it was substantially the same

thing. One could wish in retrospect, that not so much of that

broadcast had been committed to Studio 8H at NBC, and a few more

recording sessions were given to Carnegie Hall.

RS: No, I guess not. I

don’t happen to have a discography of my own things, though I’m looking

now in my studio and I suppose there are 115 records or so that I’ve

made, and there have to be one or two of them with Toscanini. But

we were doing this for broadcast, and it was substantially the same

thing. One could wish in retrospect, that not so much of that

broadcast had been committed to Studio 8H at NBC, and a few more

recording sessions were given to Carnegie Hall. RS: Pick a great school.

That’s important. Next, I’ll speak from my own frailties.

Develop keyboard facilities because they help enormously in the

accumulation of intelligence. One can simply study scores so much

faster than one can without pianistic facility. The third thing

would be don’t wait for an appointment to be the musical director of

some group, but start your own. Always have a group of some sort

functioning, whether it’s six high school kids at an evangelical church

in southwest Louisiana, or whatever, but don’t be without a performing

instrument.

RS: Pick a great school.

That’s important. Next, I’ll speak from my own frailties.

Develop keyboard facilities because they help enormously in the

accumulation of intelligence. One can simply study scores so much

faster than one can without pianistic facility. The third thing

would be don’t wait for an appointment to be the musical director of

some group, but start your own. Always have a group of some sort

functioning, whether it’s six high school kids at an evangelical church

in southwest Louisiana, or whatever, but don’t be without a performing

instrument.

|

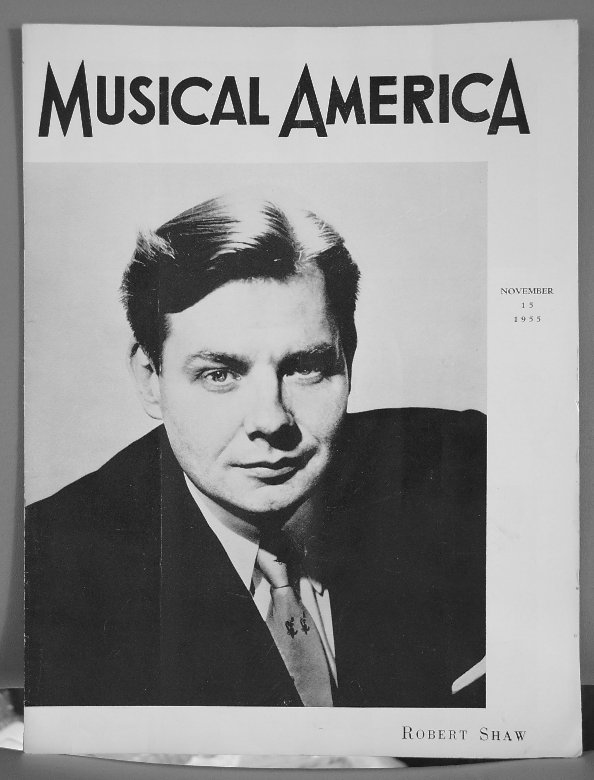

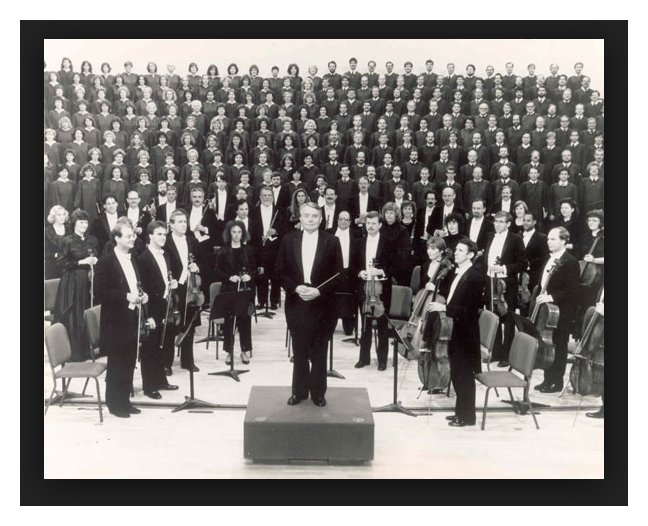

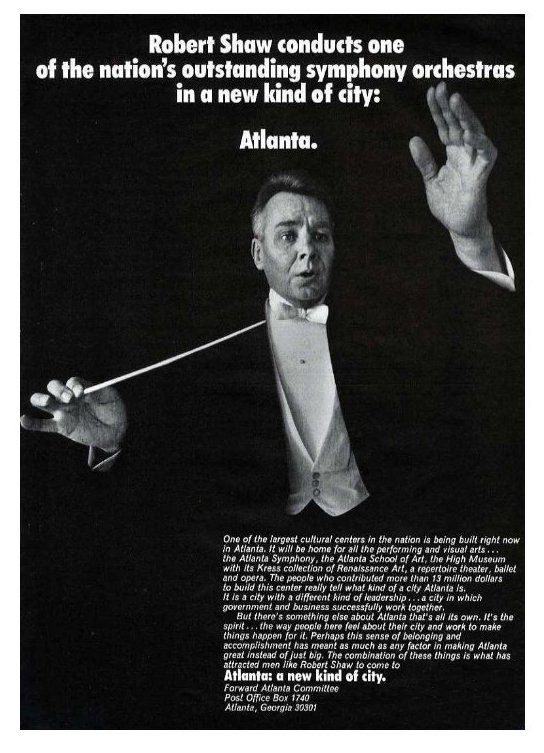

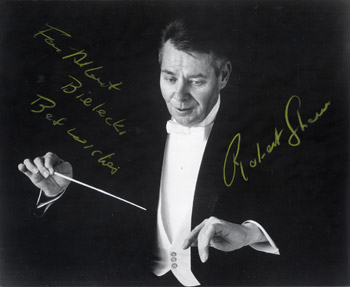

Robert

Shaw (Conductor)

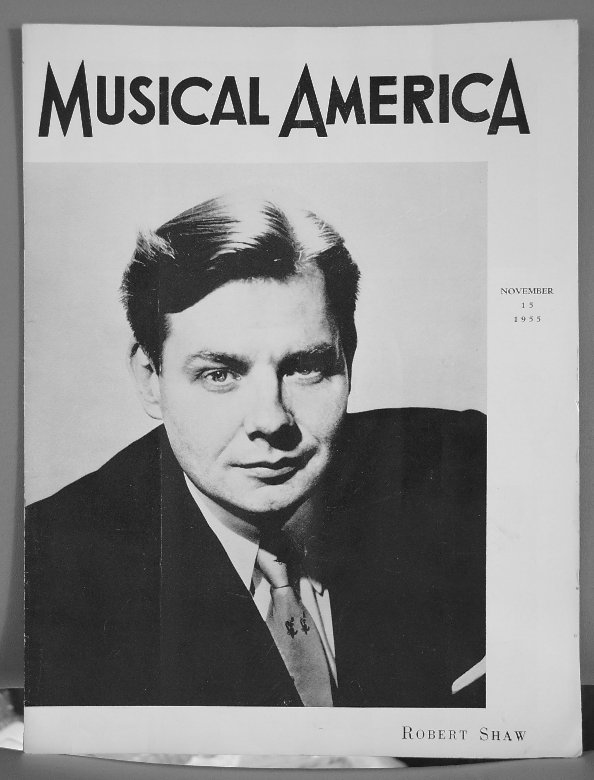

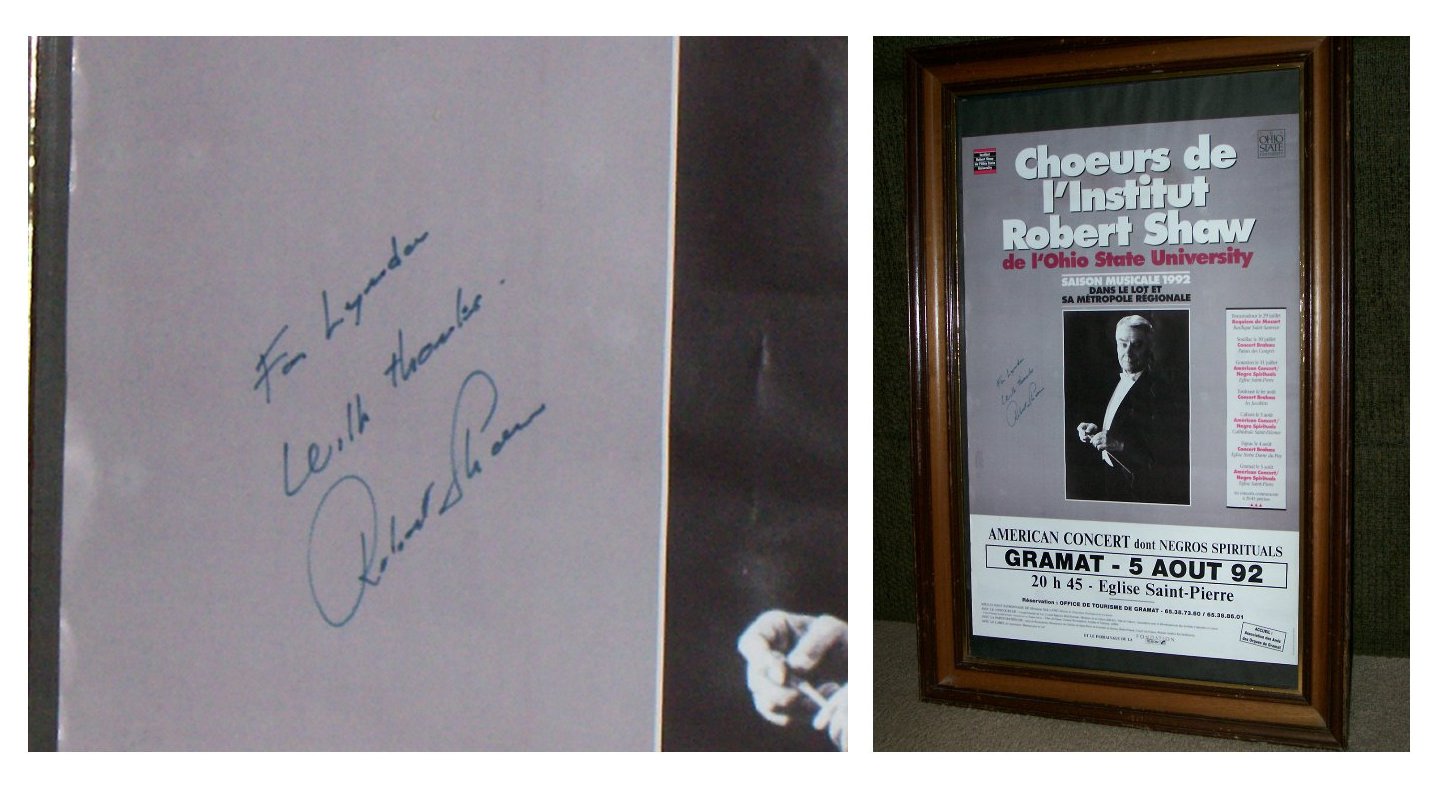

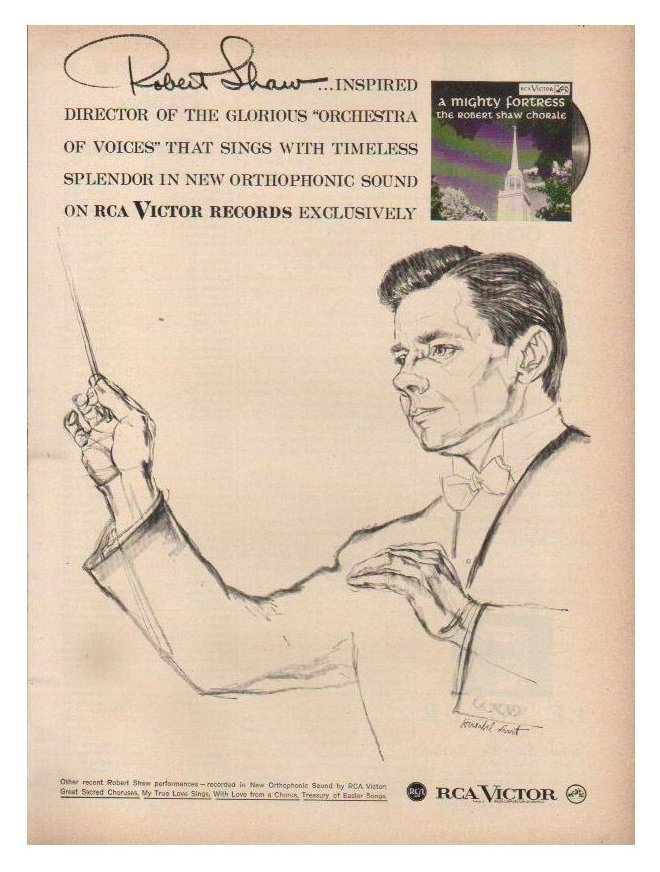

Born: April 30, 1916 - Red Bluff, California, USA Died: January 25, 1999 - New Haven, USA In his long career which spanned six decades and four cities, Robert Shaw transformed choral conducting into an art, and nearly single-handedly raised it to a new level. For more than half a century he set the standard of excellence for choral music, enjoying a status of patriarch of vocal musical interpretation in the USA.  Robert (Lawson) Shaw came from a clerical family. His

father and grandfather were ministers. More importantly, perhaps, his

mother sang in church choirs. In school his serious interests were in

philosophy, literature, and religion, but at Pomona College he did join

the glee club. Then, in a chain of events right out of a Warner

Brothers backstage musical, Shaw was asked to take over the choir for

an ailing faculty leader the same year that Fred Waring happened to be

making a film on the campus. Waring was impressed, asked him to go to

New York to develop a glee club for him. Robert (Lawson) Shaw came from a clerical family. His

father and grandfather were ministers. More importantly, perhaps, his

mother sang in church choirs. In school his serious interests were in

philosophy, literature, and religion, but at Pomona College he did join

the glee club. Then, in a chain of events right out of a Warner

Brothers backstage musical, Shaw was asked to take over the choir for

an ailing faculty leader the same year that Fred Waring happened to be

making a film on the campus. Waring was impressed, asked him to go to

New York to develop a glee club for him.As early as 1943, the National Association of Composers and Conductors cited him as "America's greatest choral conductor." Arturo Toscanini was conducting Beethoven's Ninth Symphony with his NBC Symphony Orchestra. After hearing the chorus, which had been prepared by Robert Shaw, Toscanini turned to his players and said, "In Robert Shaw I have at last found the maestro I have been looking for." With the founding of the Robert Shaw Chorale in New York in 1948, his fame and influence in the field became second to none in the world. He led the group on extensive tours throughout Europe, the Soviet Union, Latin America, and the Middle East under the auspices of the State Department. For his esteemed Chorale, he commissioned pieces from the leading composers of the day including Béla Bartók, Darius Milhaud, Benjamin Britten, and Aaron Copland. Shaw also served as music director of the San Diego Symphony Orchestra until he was recruited by George Szell to conduct the choral section of the Cleveland Symphony Orchestra. He served under Szell for 11 years. In 1967 Robert Shaw accepted the directorship of the Atlanta Symphony Orchestra, and saw it grow from a local band of 60 part-time amateur musicians to a fine major-league orchestra. When he retired in 1988, the orchestra comprised 93 professional players. He also established a magnificent choral adjunct and led the combined forces in many definitive recordings of the symphonic-choral music literature, eleven of which won Grammy awards. Shaw won four other Grammy awards and was nominated for two more. Earlier in his career, he recorded the first classical album on the RCA label to sell over a million copies. The recipient of 40 honorary degrees and citations including the George M. Peabody Medal, a Guggenheim Fellowship, and the National Medal of Arts, Robert Shaw was inducted into the American Classical Music Hall of Fame at New York's Julliard School of Music. In 1991, he received the Kennedy Center Honors, America's highest award for artistic achievement. He founded the Robert Shaw Institute which encourages the creation and production of choral art and sponsors the Robert Shaw Festival. |

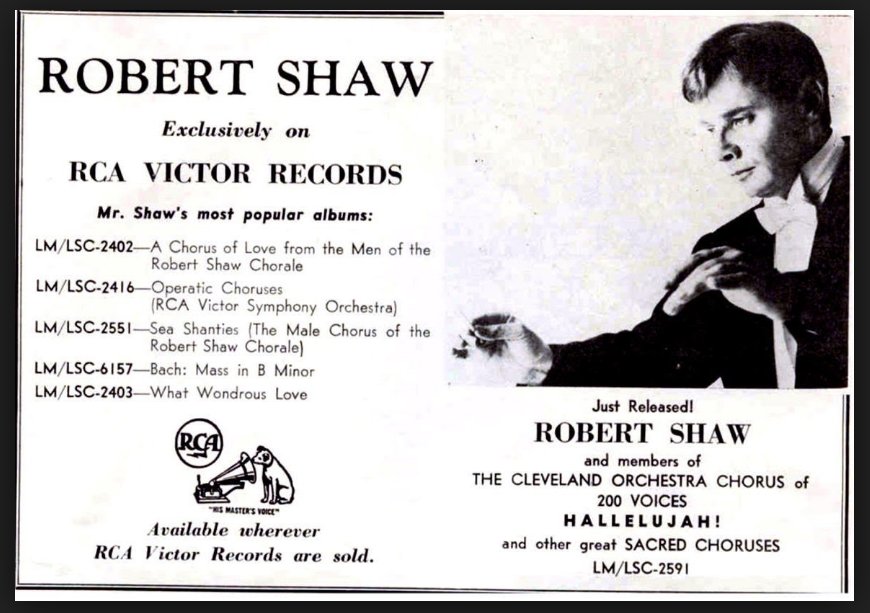

This interview was recorded on the telephone on August 24,

1985. Segments were used (with recordings)

on WNIB in 1986, 1987, 1991, 1996 and 1999. It was transcribed

and posted on this

website in 2013.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website, click here.

Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM, as well as on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio.

You are invited to visit his website for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.