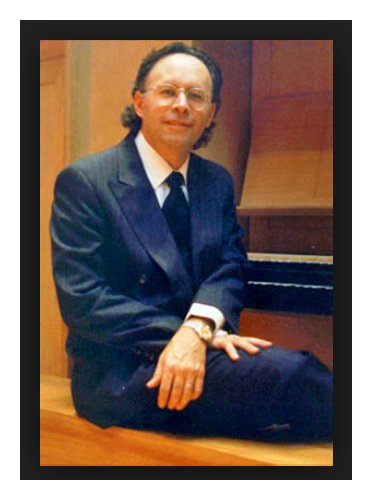

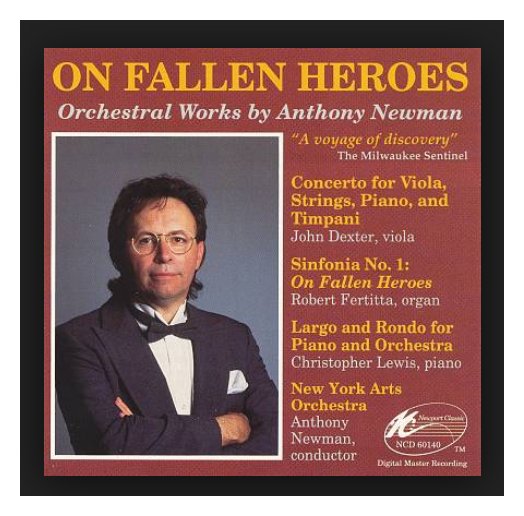

| Conductor, composer, and organ virtuoso

Anthony Newman was born May 12, 1941, in Los Angeles, later studying in Paris

under the tutelage of Nadia Boulanger and Pierre Cochereau. The recipient

of a Diplome Superieur from the

Ecole Normale de Musique,

Newman returned to the U.S. to train under composers Leon Kirchner and Luciano Berio. His

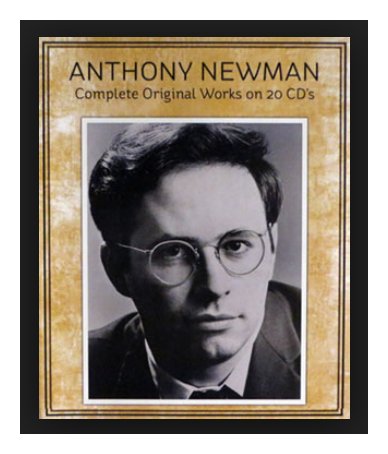

subsequent output includes no less than include five concertos, three orchestral

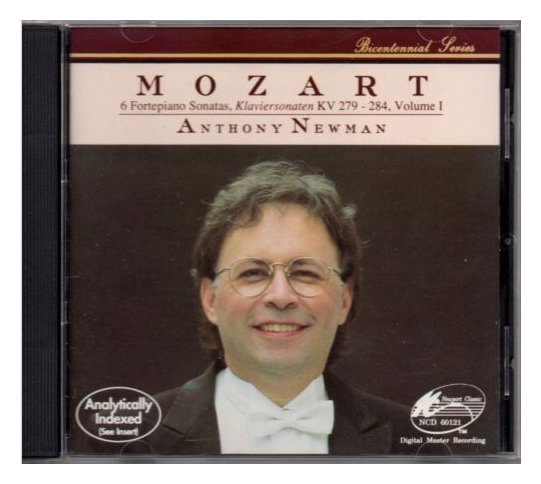

sinfonias, and an array of works for piano and organ. A prolific recording

artist with a catalog of albums spanning material from the 17th century to

the modern era, Newman also taught at Juilliard and headed the graduate music

program at Purchase College of the State University of New York. * *

* * *

Described by Wynton Marsalis as "The High Priest of Bach", and by Time Magazine as "The High Priest of the Harpsichord," Newman continues his 50 year career as America's leading organist, harpsichordist and Bach specialist. His prodigious recording output includes more than 170 CDs on such labels as CBS, SONY, Deutsche Grammaphon, and Vox Masterworks. In 1989, Stereo Review voted his original instrument recording of Beethoven's Third Piano Concerto as "Record of the Year". His collaboration with Wynton Marsalis on Sony's "In Gabriel's Garden" was the best selling classical CD in 1997. As keyboardist, he has performed more than sixty times at Lincoln Center in New York, and has collaborated with many of the greats of music including Kathleen Battle, Itzhak Perlman, Eugenia Zukerman, John Nelson, Jean-Pierre Rampal, James Levine, Lorin Mazel, Mstislav Rostropovich, Seji Osawa, and Leonard Bernstein. As conductor, he has worked with the greats of chamber music orchestras including St. Paul Chamber, LA Chamber, Budapest Chamber, Scottish Chamber, and the 92nd St. Y Chamber Orchestras. Larger symphonic groups include Seattle (over 40 appearances), Los Angeles, San Diego, Calgary, Denver, and New York Philharmonic Orchestras. No less prodigious a composer, his works have been heard in Paris, Vienna, Budapest, Krakow, Warsaw, New York, and London. His output includes 4 symphonies, 4 concerti, 3 large choral works, 2 operas, Nicole, and Massacre (in collaboration with Charles Flowers), 3 CDs of piano music, and a large assortment of chamber, organ and guitar works. His complete works are published by Ellis Press. Newman has received 30 consecutive composer's awards from ASCAP. Newman is music director of "Bach Works," New York's all Bach association, and Bedford Chamber Concerts; is on the Visiting Committee for the Department of Musical Instruments at the Metropolitan Museum of Art; and on the board of the Musical Quarterly Magazine. As a person committed to outreach, he was a volunteer for Stamford Hospital, a member of Hospice International from 1995 to 2004. Newman is music director of St. Matthew's Episcopal Church in Bedford NY. Newman is a Yamaha Artist, and a proud alumnus of Young Concert Artists. -- Two brief biographies edited

from different internet sources

-- Names which are links throughout this page refer to my interviews elsewhere on this website. BD |

Anthony Newman: Playing, of course, is something

I’ve done for years and years, and composing has been more recent.

So in a certain way the playing, as you might say, was “perfected”, which

is the wrong term, but it was brought to a reasonable level earlier.

It’s a matter of continuity, with developing new ideas about performance

rather than starting from scratch. With composing, that it is a process

of trying to discover or create an aesthetic; in other words, a new way of

expressing music, considering what we’ve gone through in the last sixty or

seventy years of various kinds of experimentation within music.

Anthony Newman: Playing, of course, is something

I’ve done for years and years, and composing has been more recent.

So in a certain way the playing, as you might say, was “perfected”, which

is the wrong term, but it was brought to a reasonable level earlier.

It’s a matter of continuity, with developing new ideas about performance

rather than starting from scratch. With composing, that it is a process

of trying to discover or create an aesthetic; in other words, a new way of

expressing music, considering what we’ve gone through in the last sixty or

seventy years of various kinds of experimentation within music. AN: Whoever employs me to play a concert or to write

a composition. That’s my employer. So if they’re happy with what

they get, then I feel that I’ve done what is my job to do. Twentieth

century music is a difficult situation because it is not a universal aesthetic.

It’s not just one way that everybody writes. It has spawned all these

little interest groups and power issues where people have created a certain

kind of music and they say, “Well, here it is. This is what it is.

This is what music is and you better like it because we’re in power and this

is what it is.” That’s very unfortunate, and perhaps an oversimplification

of what the actual process was, because there were many gifted people who

turned to what they thought must be it, because this is how people are writing.

In a way, I think the reaction to cerebral music is minimalism,

which was an aesthetic that is adopted only by a certain amount of people.

It’s not in any way universal, but it’s interesting that such a radical point

of departure could have occurred, considering how different it is from cerebral

atonalism. It’s interesting. I see minimalism as a struggle point.

It’s still struggling to find a worthy aesthetic. The worthy aesthetic

question will be answered by the next great personality that occurs as a

composer, because whoever that person is, whatever he or she writes, will

be the aesthetic leader.

AN: Whoever employs me to play a concert or to write

a composition. That’s my employer. So if they’re happy with what

they get, then I feel that I’ve done what is my job to do. Twentieth

century music is a difficult situation because it is not a universal aesthetic.

It’s not just one way that everybody writes. It has spawned all these

little interest groups and power issues where people have created a certain

kind of music and they say, “Well, here it is. This is what it is.

This is what music is and you better like it because we’re in power and this

is what it is.” That’s very unfortunate, and perhaps an oversimplification

of what the actual process was, because there were many gifted people who

turned to what they thought must be it, because this is how people are writing.

In a way, I think the reaction to cerebral music is minimalism,

which was an aesthetic that is adopted only by a certain amount of people.

It’s not in any way universal, but it’s interesting that such a radical point

of departure could have occurred, considering how different it is from cerebral

atonalism. It’s interesting. I see minimalism as a struggle point.

It’s still struggling to find a worthy aesthetic. The worthy aesthetic

question will be answered by the next great personality that occurs as a

composer, because whoever that person is, whatever he or she writes, will

be the aesthetic leader. AN: Yes. I thought the Milwaukee performance

was very fine.

AN: Yes. I thought the Milwaukee performance

was very fine.

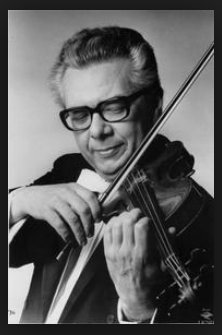

Rafael Druian was born in Vologda, Russia 250 km east of St. Petersburg (then Petrograd) on January 20, 1922. With the upheaval of the Revolution, Druian's family emigrated to Havana, Cuba when Rafael was an infant. In 1930, Rafael began studies with the Paris-born Cuban composer Amadeo Roldán (1900-1939), concertmaster and later conductor of the Havana Philharmonic. In about 1933, Rafael was admitted to the Curtis Institute in Philadelphia where he remained until his graduation in the Class of 1942. When he served in the US Army during World War II, Druian played the mellophone (a 3 valved horn) in the Army band. Following the war he was concertmaster of the Dallas Symphony from 1947-1949 under Antal Dorati. Druian followed Dorati to the Minneapolis Symphony in 1949 when Dorati became Music Director. Druian remained in Minneapolis as Concertmaster from 1949-1960, the same as Dorati's tenure there. In 1960, George Szell appointed Druian to succeed Josef Gingold as concertmaster of the Cleveland Orchestra, where he served for nine seasons. After Cleveland, Druian taught at the California Institute of the Arts in Valencia. He returned to orchestral life, being appointed concertmaster of the New York Philharmonic by Pierre Boulez from 1971-1974. Druian then pursued conducting, including festivals in New York and Alaska. He also continued teaching conducting and violin at Boston University and at his alma mater, the Curtis Institute. Rafael Druian died in Philadelphia on Sept. 6, 2002, age 80. |

AN: It’s visual in the sense that it’s mathematical.

As a visual, no. It is mental, cerebral. The mathematics is planned

out as far as the size, but I wouldn’t say it’s like shackles or anything

like that. It just says that in this section there should be 162 counts,

and the next section should have 142 counts, and the final section should

have again 162 counts.

AN: It’s visual in the sense that it’s mathematical.

As a visual, no. It is mental, cerebral. The mathematics is planned

out as far as the size, but I wouldn’t say it’s like shackles or anything

like that. It just says that in this section there should be 162 counts,

and the next section should have 142 counts, and the final section should

have again 162 counts. BD: Yes, and the performance.

BD: Yes, and the performance. AN: Well, it’s very hard to travel with harpsichords.

I never travel with them unless it’s a short distance.

AN: Well, it’s very hard to travel with harpsichords.

I never travel with them unless it’s a short distance. BD: Because they don’t go out of tune.

BD: Because they don’t go out of tune. BD: But I assume it must be worth it at the end.

BD: But I assume it must be worth it at the end.© 1989 Bruce Duffie

This conversation was recorded at his hotel near the Ravinia Festival

on October 20, 1989. Portions were broadcast on WNIB in 1996.

This transcription was made in 2014, and posted on this website at that time.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website, click here. To read my thoughts on editing these interviews for print, as well as a few other interesting observations, click here.

Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM, as well as on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio.

You are invited to visit his website for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.