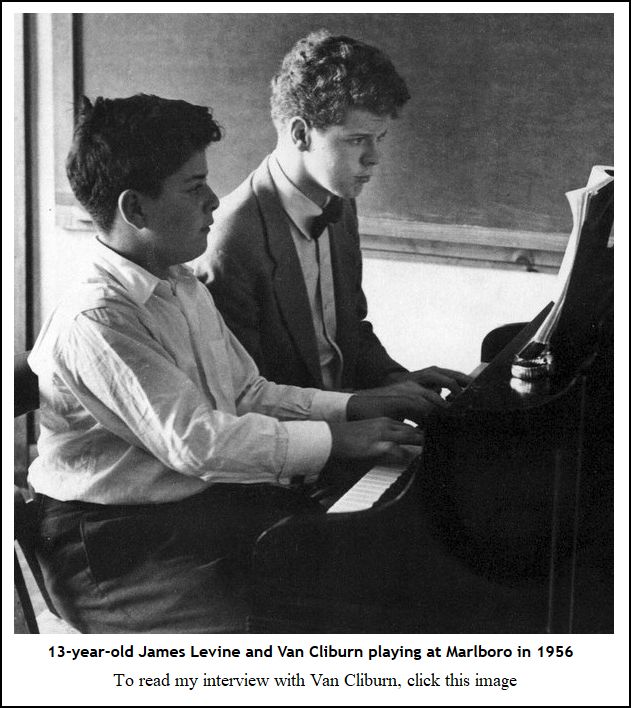

Conductor James Levine

A Conversation about Wagner

[from July, 1981]

By Bruce Duffie

This interview was held on July 14, 1981, and published in Wagner

News the following December. So, all references to productions and

events need to be placed in that context. It has been slightly re-edited

for this website presentation. Photos have been added, as well as links

which refer to my interviews elsewhere on this website.

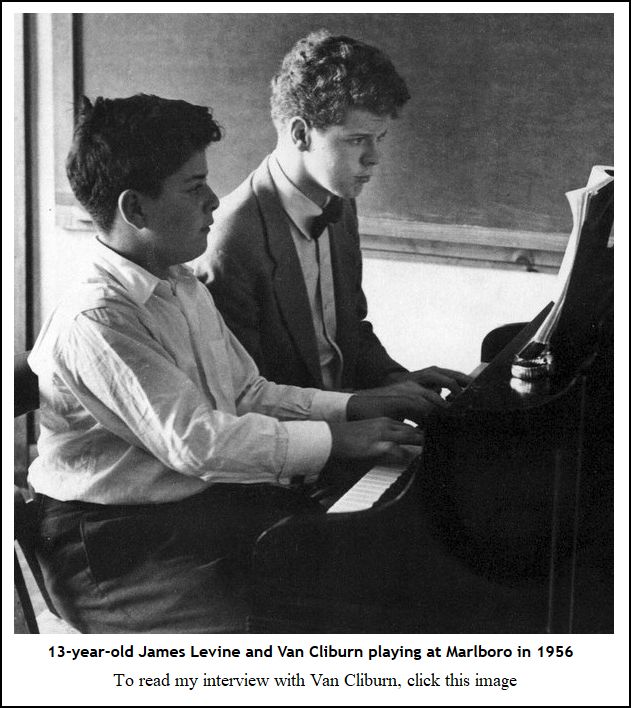

James Levine is truly a musical phenomenon, and it is at the Ravinia

Festival — the

summer home of the Chicago Symphony Orchestra — that

his versatility shows though the most. There, in addition to his duties

as music director, he conducts concerts and operas, performs as soloist

with orchestra, is a member of chamber groups, and accompanies soloists.

While he is at the Festival, he goes and goes every day, almost without

pausing to rest, and before he’s through there have been many wonderful evenings

of music and several recordings made which later become best-sellers.

And this only accounts for a few weeks of his year. After Ravinia,

he goes to Salzburg to conduct opera and concerts, and now also to Bayreuth.

Then it is back to New York for his ‘main job’ as music director of

the Metropolitan Opera, a post created for him only a year after his debut

there. With the Met, he conducts operas by the widest possible range

of composers — early works, standard romantics, verismo

thrillers, and contemporary theater-pieces. In the middle of all this

are productions of the music dramas of Richard Wagner, which he brought

back to the stage and given un-cut, this often being the first time every

note of the piece has been heard in that theater. He is sometimes

controversial, and indeed this magazine has pointed out the lack of Wagner

in the ‘Live from the Met’ series on public television. His decisions

are often criticized, and his huge workload makes an easy target for those

wishing to take shots at him. But no matter what is said, he continues

doing what he loves best — namely presenting music

to the public. When one stops to consider the sheer number of concerts,

recordings, and administrative decisions by this man, it is almost impossible

to believe that he is not yet forty years old. After the recent Ravinia

season, I had the privilege of spending a bit of time exploring the mind

of this man. Just as he does everything on a grand scale, his thought

process is deep and probing, but uncluttered. His answers so my questions

showed a clear understanding of the problems relating to the topic, and the

solutions he had arrived at concerning them. But more than that, he

is still pondering them and turning them over in his mind, and will continue

to work relentlessly, never being truly satisfied except to say that something

was the best that could be had, but it will get even better. We are

fortunate to have such a man in a position where he can bring about the fulfillment

of his visions. Our conversation was mostly about Wagner. He could

have brought in so many other items but confined his thinking to this specific

topic, and here is some of what was said . . . . . . .

Bruce Duffie: Let me start with the big question.

As Music Director of the Metropolitan Opera, what do you feel is the place

of Wagner in that house? What do you do, and what should you do?

James Levine: I don’t feel there’d be too much argument

that we tend to think of Wagner, Verdi, and Mozart as sort of operatic

pillars. That’s not to take anything away from Berg, Debussy, Tchaikovsky,

Puccini, Mascagni, Gluck, Strauss, and all the others. Certainly,

we view presenting Wagner’s works as one of the our most important functions.

Obviously, they can only be produced in a house of a certain size.

It wouldn’t have to be a house as large at the Met, but it’s interesting,

for example, that I’ve enjoyed Parsifal in our house more than anywhere

else except at Bayreuth. I’m talking about the way it looks and sounds,

not so much a question of doing it as hearing it. The special acoustic

at Bayreuth for that particular piece won’t be duplicated elsewhere, and yet

I found our acoustic conducive to it.

BD: Even though there’s no cover over the orchestra?

BD: Even though there’s no cover over the orchestra?

JL: Yes. It somehow sounds closer to my idea

of a decent representation than it does in a lot of other smaller theaters.

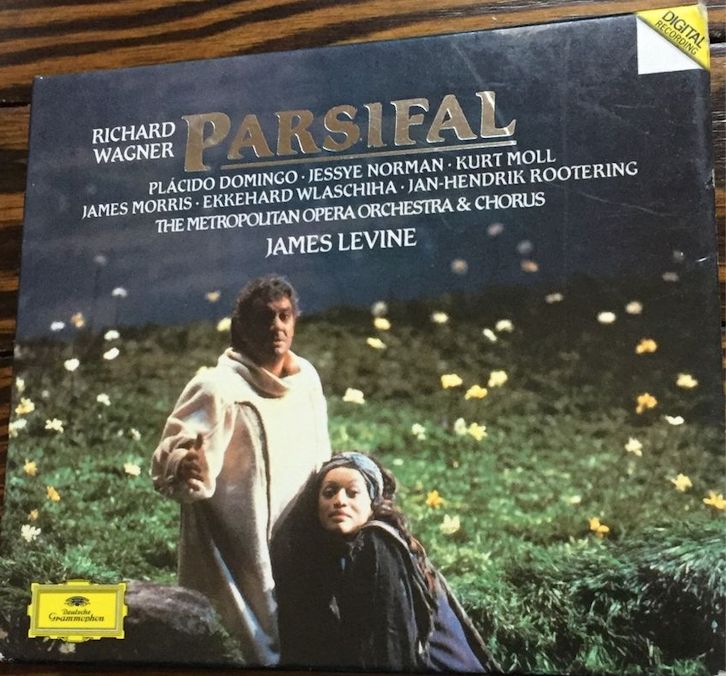

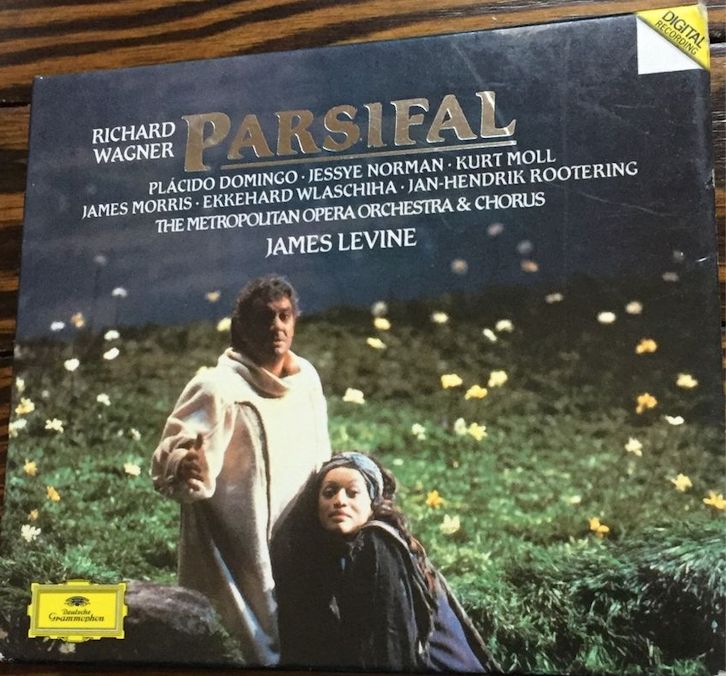

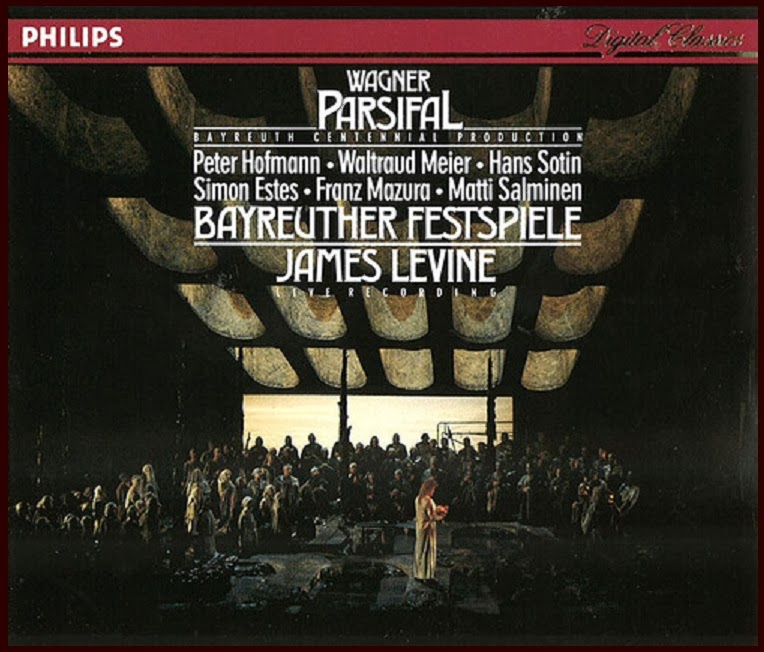

BD: Do you find this for the other Wagner works,

or just for Parsifal? [Vis-à-vis the recording shown

at right, see my interview with Kurt Moll.]

JL: Parsifal is the only one that poses the

problem, in that it was composed with a particular acoustic in mind.

It seems clear that after Wagner heard the Ring in the Bayreuth

theater, part of the texture of the orchestration of Parsifal was

written because of the way it would sound in that acoustic. There

are certainly other cases like that, but Parsifal is the most celebrated,

and certainly the greatest masterpiece we have which was written for such

specific physical circumstances.

BD: Do you feel it’s wrong to do this work elsewhere?

JL: No, I just feel that it is not going to sound

the same. So, you have the problem of trying to create an atmosphere

that’s right for this work without that physical theater to do it with.

The Bayreuth theater is unique in so many ways, and it’s interesting because

the theater itself doesn’t hold nearly as many people as a large international

opera house, and that is something Wagner wanted. The sight lines

in his theater are perfect everywhere, and the acoustic allows for tremendous

radiance, warmth, and clarity from the orchestra pit, which never covers

the singers — even those without Birgit Nilsson-sized voices.

And the way the proscenium is designed causes the audience to be able to

look at it a certain way from a certain angle. For example, from every

seat in the house you can see the floor of the stage. That changes

the spatial relationship between the size of the figures and the size of

the backcloth.

BD: This becomes especially important in the Ring

with the giants and dwarfs. The placement must be correct.

JL: Exactly, yes. And because everyone can

see the floor, it’s a completely different perspective than sitting in

the orchestra level in another theater where you can’t see that ground-cloth.

Also, there’s this wonderful empty space across the pit, between the edge

of the pit and the beginning of the stage, which has the effect of separating

the audience visually. You are often closer to the stage than in

a big theater, and yet it becomes framed a certain way. It’s a bit

like the great old moviemakers who worked in square black and white, but

could still produce a stronger sense of cinematic reality than a lot of

people have been able to since using color and all kinds of funny big shapes.

But this Bayreuth thing goes even further because people who come to Bayreuth

go there to hear the performance. This means that attending the performance

is what the person is there to do that day. It doesn’t have to be

tacked onto a working day, starting at 7 or 8 o’clock after people have

been beating their brains out working for eight hours. The fact that

the performance starts at 4 o’clock, and has long pauses, means it is the

day’s event, and is concentrated on that way. The point I want to

make is only that here we have a case of not only one of the handful of greatest

creative geniuses ever, but a man who was able to demonstrate palpably how

detailed and profound his idea is of the circumstances under which the

piece should be played, and what the ideal circumstances are. In effect,

he had to crate those conditions himself. For me, the biggest problem

conducting Wagner in any other theater is that so many of Wagner’s works

are the diametric opposite of a ‘business man’s musical’. There are

certain Italian ‘opera buffas’ and concentrated dramas of all sorts that

were clearly written to be an evening of entertainment in the theater, for

a public made up very largely of people who have been working all day, or

busy at something else all day.

BD: [Gently protesting] Something like Lulu

or Rosenkavalier does not seem to fit that category.

JL: That’s true, but the point here, where an interview

on Wagner is concerned, is that Wagner not only poses the problem that

the works are all so completely involving and so overwhelmingly full, they

are also just physically long. When I started in this job at the Met,

I went on a large campaign to get the Wagner works back on the stage without

cuts. So far, we’ve succeeded in doing the first performances in

Met history of Parsifal, Lohengrin, Meistersinger,

and Tristan without cuts. But it means you have to begin very

early, and that’s a problem for the Wagner-lover who can’t take the whole

day off — as he would if he were in Bayreuth.

It also means very short intermissions because they’re a limit to how much

you can squeeze your rehearsal say. Even if I would theoretically start

at 4 o’clock in order to have the long intermissions, that would completely

ruin the day for whatever is the next opera, which is on stage rehearsing

that day. For Götterdämmerung, we do start at 6.30

PM, but Parsifal begins at 7 and ends about three minutes to midnight,

with two very short intermissions that barely give enough time to really

recover from one act and let you prepare yourself for the next.

BD: And, of course, you’re not only asking

the audience to put in their full day and have the long evening, but there’s

no time for the artists and the orchestra to rest in between.

JL: That’s exactly right, and it’s funny... so far

I’ve gotten stacks of mail thanking me for restoring the pieces without

the cuts, but finally one letter came from someone that said perhaps it

would be better to have the cuts and bigger pauses if one is forced to put

them into this time span. Of course, I can’t subscribe to that because

for me the important thing, ultimately, is to do the piece complete.

There is no question that fitting Wagner into a repertoire opera system is

very difficult. It’s physically difficult, exhausting to rehearse

and perform, but fulfilling, overwhelming, gratifying, and satisfying beyond

any words. But it is draining beyond any words, and that’s why we’re

continually having to balance the need and desire to do the works properly.

In the last few years, we’ve given performances of Parsifal, Lohengrin,

and Tannhäuser that were better than in the last twenty years

or so.

BD: Is that because everything is

coming together for these particular operas?

BD: Is that because everything is

coming together for these particular operas?

JL: No, it tends to go in cycles. There are

periods when the right singers exist, so people put on a lot of Rings

and Tristans. Then the right soprano doesn’t exist, so they

do something else.

BD: Like Lohengrin or Holländer,

maybe?

JL: Right. This recent revival of Tristan

was in no way as successful as any Wagner we had done in the last few years,

and it was difficult to assess how much that was due to the fact that it

was the first major opera we had to put on after the labor dispute, which

means we couldn’t rehearse it the way we normally would have, and had lost

some of the originally scheduled singers. I suspect that was true,

because over the run, the performances got better, and there were some towards

the end that more resembled what we would have had on the opening night if

it were not for the labor dispute.

BD: Now you say rehearse ‘the way we normally would

have.’ Do you normally rehearse Wagner more than Puccini?

JL: Not more, but the problem can be very simply

illustrated. You can put La Bohème on two [LP] records.

That translates into such a tiny amount of time to simply play the music

through. Compare that with the running time of the first act of Parsifal.

Each is just a bit less than two hours, but what’s ironic about that is if

you have played Bohème straight through, you wouldn’t be anywhere

near as tired and psychologically drained. Your nervous system doesn’t

go through the same strain. We could probably finish a run-through

of Bohème, and go back and rehearse whole acts or sections

with great buoyancy. But after a play-through of the first act of

Parsifal, if you want to rehearse some sections, you must save it

for another day. It’s not a question of rehearsing it more, it’s

that it takes longer to rehearse.

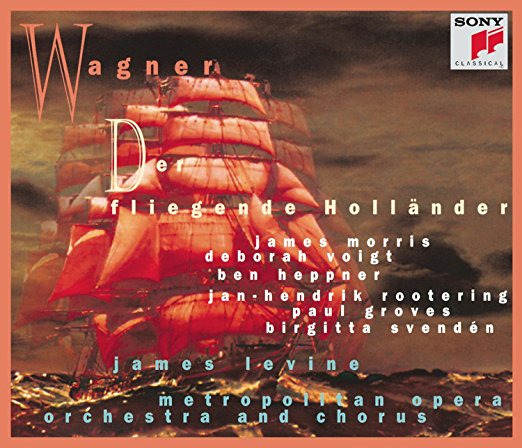

BD: Does Holländer come closer to the

‘standard’ opera than Parsifal?

JL: I think Holländer and Tannhäuser

are the two operas that can be performed, in physical terms, most like the

rest of the repertory. We can begin Tannhäuser at 8 o’clock,

and end easily before midnight. So, that is for us like Aïda,

or Otello¸ or Carmen in terms of time. In terms

of drain, Tannhäuser strikes the balance. I’ve commented

on this before, and some people don’t seem to understand what I’m getting

at. There are certain pieces which may be very moving, very overwhelming,

but after they are over, the main feeling you have is that of being completely

drained, completely exhausted. I don’t mean that they’re in any way

less good at all, but I know that I could not conduct Parsifal two

days in a row.

BD: Could you conduct anything else the day after

Parsifal?

JL: Yes. Physically, Parsifal is not

so draining. It is draining on the nervous system and on the psyche.

BD: Not so much on the arms?

JL: Right. The most tiring Wagner opera on

the arms is Lohengrin because it’s a piece which is physically laid

out for a very large space. It’s very tightly organized rhythmically,

and requires a great big and incisive beat throughout almost all of it.

And at the same time as you’re working that hard physically, you have a

very fragile atmosphere to sustain. In Parsifal, where the

atmosphere is fragile to sustain, a lot of the involvement is with one or

two characters, and there is a greater variety of tempo and meter.

It’s funny, this business of things that make one psychologically tired,

and things that make one physically tired. I’m not complaining about

it making one tired. I think it’s perfectly fine. When I say

things like that, people think I don’t love it as I do.

BD: It’s a really ‘good’ tired?

JL: Yes, it’s really ‘good’ tired. You can

conduct a Mozart opera, or even a tragic Verdi opera, and feel somehow

that it has re-energized you as you were doing it. But when you get

to the end of Parsifal or Tristan, the exhaustion is so profound

psychologically and emotionally and physically, that the only way to get

built up again to do it again is to wait a bit. Now I don’t mean to

imply that Tannhäuser, because it is less exhausting is a less

successful piece. I object vehemently to the argument that these early

pieces are somehow less valuable than the later ones. That’s an argument

which irritates me in general, and particularly when you’re dealing with

a genius like Wagner. Any idiot can see that Parsifal, and

Tristan, and Meistersinger are consummate masterpieces which

have no flaws, but the fact is that Lohengrin, or Holländer,

or Tannhäuser are early works with tremendous originality.

Just as the later works have things the early works don’t have, the early

works have things the later ones don’t have. Tannhäuser

is a singularly successful piece that puts forward a dramatic issue in perfect

balance and form in a really well-executed performance. People seem

to make wonderful contact with it, but now it’s going through a period in

Germany and Austria where it’s becoming something of a cliché.

Now when you mention it, people moan and groan, but I think that’s because

for so many years it was in the over-used category.

BD: Was it the Wagner anybody could do, so they did

it too much?

JL: Exactly.

* * *

* *

BD: You were talking about the early works, so let

me ask you about the three really early works — Rienzi,

Feen, and Liebesverbot. What place do they have, if

any?

JL: It’s interesting. One would love to do

them because one would love to make accessible for any opera-lover more

and more repertory. And people misunderstand this, too. The

moment we announce Liebesverbot, everyone would think we were dumping

Tristan. It’s the damnedest thing, this either/or business.

I would love to be able to do those works. It’s simply the law of

the list of pieces we would like to do versus the number of pieces we can

do in any given season. That is what produces the unlikelihood that

we will do any of them in the near future. I keep flirting with Rienzi,

and keep finding that the closer I get to the tangible possibility of doing

it, the more sense it makes to do another revival of a production we already

have. Here’s an illustration: we do not have a Holländer

production at the Met. Now that’s an opera I could cast and play a

lot if I had a production. So, at the next opportunity, when it comes

to a choice of that or Rienzi, Holländer will be done

because we need it and can use it.

BD: But if it came down to a choice of Rienzi or

Prophète again?

BD: But if it came down to a choice of Rienzi or

Prophète again?

JL: Oh, that’s exactly where it is. If we got

to that sort of decision, we’d do Rienzi without question.

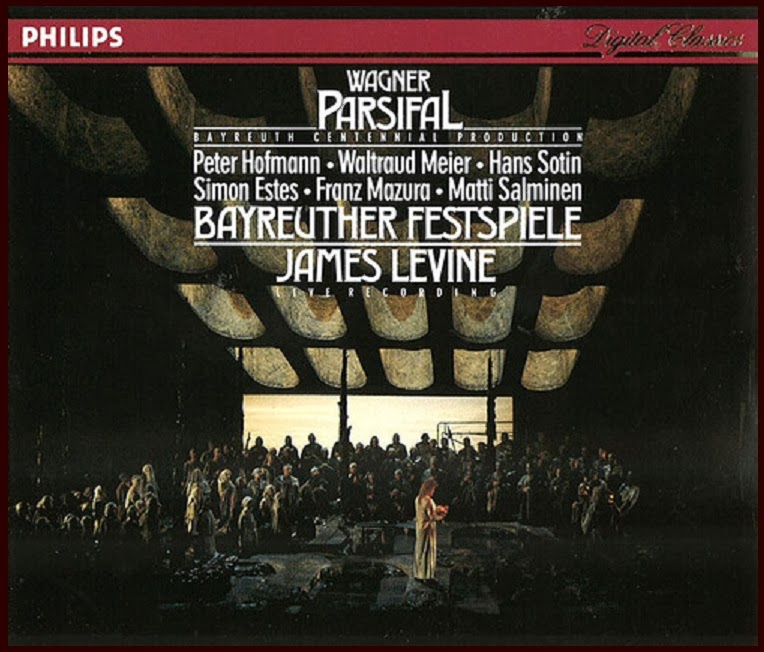

BD: We’ve talked a lot now about Wagner in ‘your’

theater, namely the Met, but I understand you will be doing the centennial

Parsifal at Bayreuth? [Recording of this production shown

at right. See my interviews with Hans Sotin, and Simon Estes.]

JL: It’s fascinating about this Bayreuth Parsifal.

Wolfgang Wagner was asking me to come there every year, and I kept turning

it down because I had this prior affiliation with Salzburg. Finally,

he wrote me a cable and said, “I know you have an

affiliation with Salzburg, but what can I do to get you to come?”

Sure enough, the thing I want most to do there is Parsifal because

it was written for Bayreuth. Even though I wouldn’t mind conducting

all the operas, or any of the operas, Parsifal means the most to

me. It was the first opera I saw at Bayreuth, and he sent me a cable

immediately back that night, offering me the centennial production.

BD: Did you see the legendary Wieland Wagner production?

JL: Oh, yes, many times, and Wolfgang has had one

in there for five years. I’ve seen it three of those years, so I’m

looking very much forward to it.

BD: I hope it goes super well!

JL: Well, you can’t tell until you do it. It’s

a crisis time for enough of the right kind of singers, and the more people

get involved with how it looks, the more difficult it becomes to cast.

BD: How far ahead can you work with a singer and

place him in a role?

JL: You mean booking?

BD: No, artistic.

JL: That’s completely individual. Some people

are quick studies, and have a culture to go with it, so you can adjust

subtleties quickly. Other people need a really long, long adjusting

time. It also depends on how intelligent they are, what their culture

is, what their experience is, and what period they’re going through vocally.

Everything is individual.

BD: Let me ask you more about singers. It’s

so difficult to cast Wagner, so from your perspective, how do singers of

today compare with the singers on the horizon, and those just retired?

JL: My feeling is that when it comes down to the

question of Wagner singers, an awful lot has to do with how close the totality

comes to what I think is a communicative, valid representation of the piece.

I’ve heard performances of Wagner operas in which the ensemble was so good,

the conducting was so good, the production was so well-conceived, the text

was so expressively delivered that I had a much better time than at a performance

in which a whole lot of very strong thrusting pear-shaped tones came out

of the mouths of people from whom I could understand very little text, and

I could agree with the very few tempi, and I thought the production was a

travesty, etc. So, with Wagner, you’re always taking a tremendous gamble

because the sheer demands for the conductor, stage director, orchestral musicians,

and singers are such that in any generation there are fewer people who

can deal with them than there are who can deal with other styles.

This was always true. Go back to the great ‘golden age of Wagner performances’

in the 30s! Listen carefully, and you hear an incredible amount of

unsuccessful results. You also hear many great things.

BD: When you don’t have a Lucia to sing the part,

you simply don’t do the work. But because there’s so much clamor to

do Wagner, do you have to do him even if it’s less successful?

JL: It’s funny you should mention that because I’ve wrestled

with that a lot. This year’s Tristan at the Met I keep coming

back to as the most interesting example of this question. A little

history has to be understood here. I had already done at the Met Holländer,

Tannhäuser, Lohengrin, and Parsifal. I thought

for the most part we did them well, apart from whatever controversy there

was about the visual aspects of the Holländer production.

The casts, the level of ensemble, the performances seemed to be for the most

part successful... and by ‘successful’

I mean they were well attended, and people liked them. From my point

of view, what’s a success has to do with whether I think the performance

is faithful to the composer, but that’s a whole other subject. When

I looked at the history of these works at the Met, the last twenty years

of Parsifals, for instance, weren’t as good as that 1979 series we

did with Vickers and

Ludwig. I thought I hadn’t ever seen or heard a Tannhäuser

that was as much of a complete success as this one we did. There

were aspects of the Lohengrin production that were not my cup of tea,

but at least we had the cuts open, and we had a good cast. Now we

decided it was time to do a Tristan revival. Why was it time

to do a Tristan revival? There are few people who can sing Tristan!

Well, here we have this wonderful production, and it hasn’t been played

for seven years. I thought if we don’t play it again, it could be

ten year or fifteen years, or God knows how long. Now after a history

of having done Wagner there in recent years — at least

the pieces we chose to do — the way we tried to do

them brought them off closer to the successful executions of the works than

had been done there in many years. This was for a very good reason:

during those years, which coincided, say, with Birgit’s years, there were

lots more Rings and Tristans, and lots fewer Parsifals

and Tannhäusers.

JL: It’s funny you should mention that because I’ve wrestled

with that a lot. This year’s Tristan at the Met I keep coming

back to as the most interesting example of this question. A little

history has to be understood here. I had already done at the Met Holländer,

Tannhäuser, Lohengrin, and Parsifal. I thought

for the most part we did them well, apart from whatever controversy there

was about the visual aspects of the Holländer production.

The casts, the level of ensemble, the performances seemed to be for the most

part successful... and by ‘successful’

I mean they were well attended, and people liked them. From my point

of view, what’s a success has to do with whether I think the performance

is faithful to the composer, but that’s a whole other subject. When

I looked at the history of these works at the Met, the last twenty years

of Parsifals, for instance, weren’t as good as that 1979 series we

did with Vickers and

Ludwig. I thought I hadn’t ever seen or heard a Tannhäuser

that was as much of a complete success as this one we did. There

were aspects of the Lohengrin production that were not my cup of tea,

but at least we had the cuts open, and we had a good cast. Now we

decided it was time to do a Tristan revival. Why was it time

to do a Tristan revival? There are few people who can sing Tristan!

Well, here we have this wonderful production, and it hasn’t been played

for seven years. I thought if we don’t play it again, it could be

ten year or fifteen years, or God knows how long. Now after a history

of having done Wagner there in recent years — at least

the pieces we chose to do — the way we tried to do

them brought them off closer to the successful executions of the works than

had been done there in many years. This was for a very good reason:

during those years, which coincided, say, with Birgit’s years, there were

lots more Rings and Tristans, and lots fewer Parsifals

and Tannhäusers.

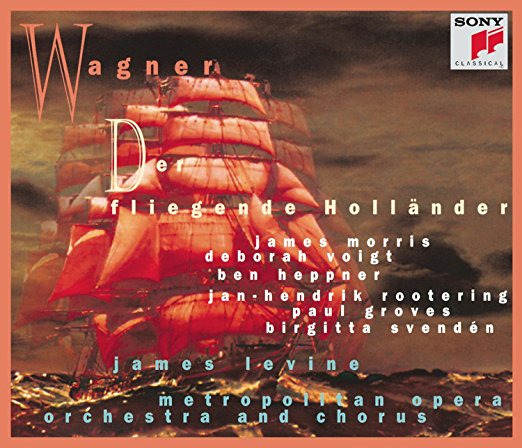

BD: We have to get through the times from the Flagstad/Melchior

Tristans, to the Traubel/Svanholm Tristans to the Harshaw/Liebl Tristans

to the ones with Nilsson and Thomas? [Vis-à-vis the recording

shown at left, see my interview with Paul Groves.]

JL: Right, and there’s so much to learn in these pieces.

There’s so much to come in contact with in these pieces that it’s worthwhile

to have them in the repertoire if you can do any kind of justice to them

at all, because of the possibility of there being, in any audience, people

who are hearing the piece for the hundredth time, and people who are hearing

it for the first time, and people who, over a long span, will then hear quite

a lot of them.

BD: This is why I get the feeling that you’re

looking at the long, multi-year cycle, rather than this year’s repertory

alone. A seasonal subscriber, or radio listener, who’s going to come

for twenty years, will see balance.

JL: There has to be a sense of perspective.

I thought if we do this Tristan and put it back in our repertory so

that it’s now taken care of by our new lighting designer, by our new technical

people, and I’ve conducted it and gotten to work on it with this company,

then when we do a revival in the centennial year, and we’ll have a completely

different thing to work with when we start than we would have if we hadn’t

done this revival. I shudder to think what it would be, after what

would then have been ten years, to try and redo that. It’s a piece

that needs the kind of rehearsal time like a new production, and yet if

it’s not a new production you don’t have the possibility to give it that

much rehearsal. I also thought the rest of the world is doing Tristan

— San Francisco, Bayreuth, Munich. Granted, their halls

aren’t as big as ours, and of course people said to me I was crazy and couldn’t

cast it, and it won’t be good. But, I thought, we know that there

is no validity to doing Lucia without a Lucia. We know there

is no validity doing an Aïda without an Aïda, but when we

look carefully at the performing history of Wagner, did people feel that

Windgassen was invalid because he wasn’t Melchior? Or that Harshaw

and Liebl were no good because they weren’t Flagstad and Melchior?

Did people feel that Vinay, with his wonderful communicative power, and

his wonderful personality, and his sense of commitment, wasn’t good enough

because he wasn’t Melchior? What I was curious to find out was can

one do a performance of this piece in which we may not have the vocal power

we had for this piece twenty years ago? As I said, the labor dispute

came right up to it. I had the option to either cancel it or try to

do it anyway. It was sold out, people wanted it, I thought we must

try. If we just cancel it, we will have lost an invaluable piece of

trying to get the mosaic put back together for the future seasons anyway.

Canceling it has tremendously horrible artistic and financial ramifications,

so we tried to do it. I had two fascinating reactions. Some people

were very hostilely against it. They said it was no good, and they

carried on that it was lousy. But I got a letter from a Wagner-lover

who goes every year to Bayreuth, and he had heard these people singing their

performances all around in the other theaters, and he said, “I

think you’re casting pearls before swine.” I

asked what he meant, and he said, “I don’t think these

people understand that it’s either we do this or we can’t have the pieces

at all.” Then I had a reaction that proved to

me what it was I had been looking for. We did a non-subscription performance

for an audience that paid money to come and hear that specific performance.

It was not on the series. It was exactly the same cast that had sung

the premiere night, and that audience stood there and screamed and yelled,

and carried on, and brought down the house for a half hour after the performance

was over. Now I know that performance was better than it was on opening

night because at the opening night, as I explained before, we weren’t ready.

Yet, it wasn’t that much better. It was still the same singers;

it still wasn’t turned into one of the greatest performances of Tristan

that had ever happened. Yes, I was a little close to having the line

that I was trying for; a little closer to having the assets that this situation

had in the foreground, and again, you’ll never be able to get people to

agree about whether or not those assets are enough, or whether it should

be dropped. My point of view is these works of art are so significant,

that only by keeping them alive in the repertoire will singers keep coming

along learning to adapt to their demands. There’s no question if we

played ourselves the tapes of the last twenty years of Bayreuth performances

of these works, we would find a year when this opera clicked, and a year

when that opera really clicked, and a whole lot of years when the casting

wasn’t the greatest, or a conducting gamble didn’t pay off, or the production

really wasn’t so good or too bad. You also get a certain irrationality

where the audience will boo the house down for the Chéreau’s Ring

the first year, and stand there and cheer it to bits on the closing night

five years later.

BD: But how much of that is the same audience?

BD: But how much of that is the same audience?

JL: Right! Not only that, but how much has

the production metamorphosed? Often, subtleties can shift the balance

in a place like that. There’s another element that you really have

to get into, which is really important, and that is the atmosphere of a

piece which is so complex that they are more profoundly affected by the state

of mind in which the listener comes into the theater than any other music

in the world.

BD: How much does your living another five years have

to do with your accepting a Chéreau Ring?

JL: That’s right. Also, there’s another element.

I have a theory about the Tristan Prelude, which is that people play

it too fast because it has become a concert excerpt. It is now a

familiar hit concert excerpt, and its function to this huge drama has gone

down the tube a bit.

BD: Is it following The Ride of the Valkyries

down the same tube?

JL: Yes. What bothers me is that very clearly

Wagner has written a prelude which is a kind of seed, a little cell out of

which this huge thing is going to grow. The motive that begins the

Tristan Prelude is marked in the score ‘langsam und schmachtend’,

but it’s going to occur over and over again. It also occurs with a

huge pause after it in both beats and fermatas. But imagine a man who

rushes into the theater all agitated. Then you start the piece, and

his pulse is racing while yours is going much slower. For him it’s

way too slow. For the person who has the ticket for Tristan

that they’d saved liked crazy to get, and they’ve slept late, and they’ve

looked through the libretto, and they came composed, they’re having a great

time. Yet they are each ready to tell you objectively that it’s too

fast or too slow. How can it be that the timings of Parsifal

Act I in the Bayreuth catalog vary from Strauss’s approximately an hour and

a half to Toscanini’s almost two hours and fifteen minutes? Was one

of them wrong? We’re talking about Strauss and Toscanini, not about

Joe Blow and Jack Doe. With pieces this long, this complicated, this

singular, the individual members of the audience are having an even more

diverse experience than they would be having at a piece composed on a simpler

scale with simpler elements.

BD: Do you just do the piece the way you feel, or do

you try to change it at all for the circumstances?

JL: I agonize over every detail, trying to find what

seems to be the best possible representation of the composer’s intention.

Yet, there isn’t any doubt that, as we said earlier, the demands

in opera — the voice, the visual, the dramatic, the

text, the pronunciation of the text, the inflection of the text, the relationship

of these elements to one another, the balance between the pit and the stage,

the character of the sound, the rhythmic pace, the ensemble, the organization

of all these nervous systems functioning in some kind of chemical harmony

— is difficult to achieve in a classical symphony, or a string

quartet, or in a standard repertory short opera that is even a light comedy.

In these Wagner pieces, which are the greatest challenge, you have the

potential for the greatest risk, the greatest catastrophe, and the greatest

satisfaction. The point I’m trying to make out of all these words

about the Tristan is only that here we have a performance which,

even in terms of physical circumstances, couldn’t be at all that I’d imagined

when I planned it, and yet we have reactions from incredible overt hostility

to incredible overt idolatry.

BD: Just like the reactions the piece itself produces?

JL: Right. Wagner, being as much of a genius as

he was, being as strong an individual as he was, dealing with such extremes

of feeling, excites a kind of irrational ‘partisanism’ more than any other

figure in nineteenth century music, and it has some funny sides to it.

For instance, when Tristan was written, the music world divided into

two camps. There were people who thought this was really the greatest

thing that ever happened. This must be the most phenomenal work of

art of the nineteenth century. Then there were those who thought this

piece was a catastrophe, a disaster. But what truly fascinates me is

that the ones who thought it was a disaster didn’t perform it, but the ones

who thought it was great, performed it and cut it to shreds. That

truly fascinates me. The people who didn’t love it didn’t touch it.

The people who did love it were in there doing it, but not accepting it

as it is. Even now there are Wagnerites and anti-Wagnerites arguing

like mad about this human being and his music. I am always fascinated

by people who are vehemently opposed to this or that singer, and I always

want to say to them, “Then don’t go!”

BD: Come back next month!

JL: Yes! Come and listen to what pleases you.

I don’t understand why everything has to be please everybody. I don’t

understand why people would ever attempt to evaluate art like one evaluates

a popularity contest. If you’re going to say that it’s better because

more people like it, then a baseball game is better than a string quartet.

I just can’t see that. I keep thinking with this art form, the more

we do them the more possibility there is that we do them better and better.

That is why, when we bring this Tannhäuser back we run it three

seasons in a row. That way I can rehearse it three seasons in a row,

so whatever gets settled in the first run that we don’t think is good enough,

we have a chance maybe to improve the next time. Another thing we

started was trying to do Parsifal every season. We lost it

this season because of the labor dispute, and we lost this whole next Ring

cycle, but we’ll simply start that over from scratch and plan it again.

BD: All the Ring operas are gone?

JL: No, but the cycle is gone. There will be

two of them this year and two next year. Somebody always says, “But

they do it in Seattle,” and I say, “I

know. What do you want from me?” They

have a Ring festival, and I’m running a repertory opera theater with

a larger and more varied and consistently star-cast repertory than any other

international opera house. Even in this crippled labor dispute year,

I got the three-act Lulu, I got Parade, etc. In these

years, the Wagner operas have been very well represented, with some of the

operas that weren’t done so much before.

* * *

* *

BD: What about doing opera in concert? How is your

interpretation different from a staged performance?

BD: What about doing opera in concert? How is your

interpretation different from a staged performance?

JL: These questions are so hard because they go on and

on. They’re things a man ruminates about, turns over, and keeps going

at.

BD: I’m just trying to pin you down to how you feel

today, which won’t be the same as yesterday or tomorrow.

JL: Okay. I like doing concert opera, but the

problem you always get into, when you say something like that, is that

people leap to conclusions that are different from what you’ve said.

It’s this either/or thing, again. If you do an opera in concert, people

assume immediately that you think it’s better that way than on the stage.

I don’t see why a concert performance can’t have its own validity.

There is no doubt, above all, Wagner was writing music dramas

— theater pieces, ultimately even for his specific theater.

All that we’ve been talking about is proof that composers feel strongly about

everything having to do with the way the piece is rendered. So, there’s

no question that when you do a concert performance of a Wagner work, you

accept that you are going to listen to the music. We know it’s not

a visual experience, but we accept that for what it is. It’s sort of

like sitting at home listening to a recording. For me, the value of

a concert performance is just that — to

be able to concentrate on the music alone, to be able to let the visual imagination

go where it wants. I never want concert performances to replace staged

performances, but I think there’s a perfectly good validity to do them.

BD: Is opera a series of compromises all the way?

JL: Well, no, I don’t feel that way about it.

My view is that an opera is surely the hardest kind of work of art to bring

into reality in any kind of performance, simply because it has the largest

number of variables. Opera has so many things that have to happen

in the right proportion and in the right relationship to one another in

the right balance. If you took these elements separately, and then

multiplied them by the number of people involved in producing them, the

likelihood of achieving something like what was envisioned by the composer

and librettist is a one-in-a-million shot. Yet, that one-in-a-million

shot is so satisfying and so fulfilling when it happens that it seems somehow

worth all the rehearsing, all the gamble, all the frustration, all the

near-misses. Even a performance that is not a complete success can

still have some very illuminating things. Out of the hundreds or thousands

of performances I’ve heard, I almost never have walked away with the feeling

that something couldn’t have been better. But that doesn’t necessarily

make the performance unsatisfactory.

BD: I would think that most times it would be a near-miss,

and every night it’s a near-miss from a different angle.

JL: That’s exactly right.

BD: You’ve given us a great deal to think about.

Thank you.

JL: Thank you, Sir. I hope it’s of value.

==========

========== ==========

--- --- --- --- ---

---

========== ==========

==========

© 1981 Bruce Duffie

This conversation was recorded backstage at the Ravinia Festival

in Highland Park, Illinois, on July 14, 1981. Portions were broadcast

on WNIB in 1989 and in 1993. This transcription was made

and published in Wagner News in December of 1981, and in Opera

Scene in July of 1982. It was slightly re-edited in 2018, and

posted on this website at that time. My thanks

to British soprano Una Barry for her help in preparing this website

presentation.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed

and posted on this website, click here.

Award -

winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical

97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical

station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared

in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues

his broadcast series on WNUR-FM.

You are invited to visit his website for more information about

his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews,

plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call

your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who

was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You

may also send him E-Mail with comments,

questions and suggestions.

BD: Even though there’s no cover over the orchestra?

BD: Even though there’s no cover over the orchestra?  BD: Is that because everything is

coming together for these particular operas?

BD: Is that because everything is

coming together for these particular operas?  BD: But if it came down to a choice of Rienzi or

Prophète again?

BD: But if it came down to a choice of Rienzi or

Prophète again?  JL: It’s funny you should mention that because I’ve wrestled

with that a lot. This year’s Tristan at the Met I keep coming

back to as the most interesting example of this question. A little

history has to be understood here. I had already done at the Met Holländer,

Tannhäuser, Lohengrin, and Parsifal. I thought

for the most part we did them well, apart from whatever controversy there

was about the visual aspects of the Holländer production.

The casts, the level of ensemble, the performances seemed to be for the most

part successful... and by ‘successful’

I mean they were well attended, and people liked them. From my point

of view, what’s a success has to do with whether I think the performance

is faithful to the composer, but that’s a whole other subject. When

I looked at the history of these works at the Met, the last twenty years

of Parsifals, for instance, weren’t as good as that 1979 series we

did with Vickers and

Ludwig. I thought I hadn’t ever seen or heard a Tannhäuser

that was as much of a complete success as this one we did. There

were aspects of the Lohengrin production that were not my cup of tea,

but at least we had the cuts open, and we had a good cast. Now we

decided it was time to do a Tristan revival. Why was it time

to do a Tristan revival? There are few people who can sing Tristan!

Well, here we have this wonderful production, and it hasn’t been played

for seven years. I thought if we don’t play it again, it could be

ten year or fifteen years, or God knows how long. Now after a history

of having done Wagner there in recent years — at least

the pieces we chose to do — the way we tried to do

them brought them off closer to the successful executions of the works than

had been done there in many years. This was for a very good reason:

during those years, which coincided, say, with Birgit’s years, there were

lots more Rings and Tristans, and lots fewer Parsifals

and Tannhäusers.

JL: It’s funny you should mention that because I’ve wrestled

with that a lot. This year’s Tristan at the Met I keep coming

back to as the most interesting example of this question. A little

history has to be understood here. I had already done at the Met Holländer,

Tannhäuser, Lohengrin, and Parsifal. I thought

for the most part we did them well, apart from whatever controversy there

was about the visual aspects of the Holländer production.

The casts, the level of ensemble, the performances seemed to be for the most

part successful... and by ‘successful’

I mean they were well attended, and people liked them. From my point

of view, what’s a success has to do with whether I think the performance

is faithful to the composer, but that’s a whole other subject. When

I looked at the history of these works at the Met, the last twenty years

of Parsifals, for instance, weren’t as good as that 1979 series we

did with Vickers and

Ludwig. I thought I hadn’t ever seen or heard a Tannhäuser

that was as much of a complete success as this one we did. There

were aspects of the Lohengrin production that were not my cup of tea,

but at least we had the cuts open, and we had a good cast. Now we

decided it was time to do a Tristan revival. Why was it time

to do a Tristan revival? There are few people who can sing Tristan!

Well, here we have this wonderful production, and it hasn’t been played

for seven years. I thought if we don’t play it again, it could be

ten year or fifteen years, or God knows how long. Now after a history

of having done Wagner there in recent years — at least

the pieces we chose to do — the way we tried to do

them brought them off closer to the successful executions of the works than

had been done there in many years. This was for a very good reason:

during those years, which coincided, say, with Birgit’s years, there were

lots more Rings and Tristans, and lots fewer Parsifals

and Tannhäusers.  BD: But how much of that is the same audience?

BD: But how much of that is the same audience?  BD: What about doing opera in concert? How is your

interpretation different from a staged performance?

BD: What about doing opera in concert? How is your

interpretation different from a staged performance?