| Helge

Antoni

was born in Malmö (Sweden), on April 25, 1956. He studied at the

Malmö Academy of

Music with Stanislav Knor, and made his professional debut playing Franz

Berwald's

Piano Concerto. In 1979 he was the first Swedish musician

to be awarded a

British Council Fellowship, and continued his studies with Peter Feuchtwanger

in London

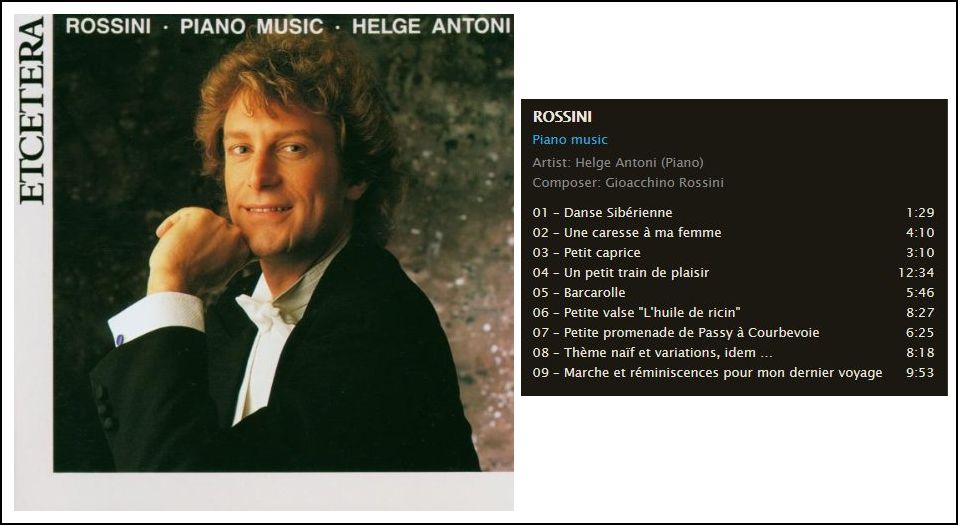

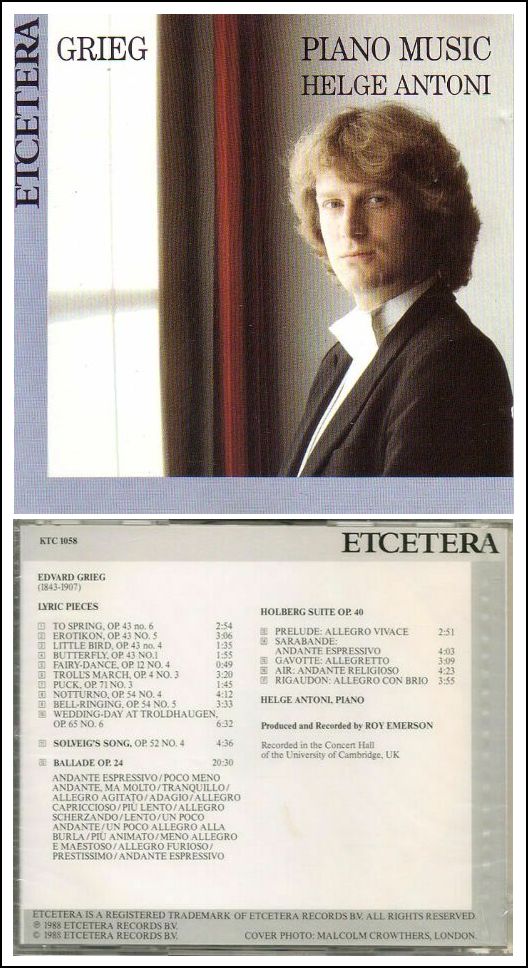

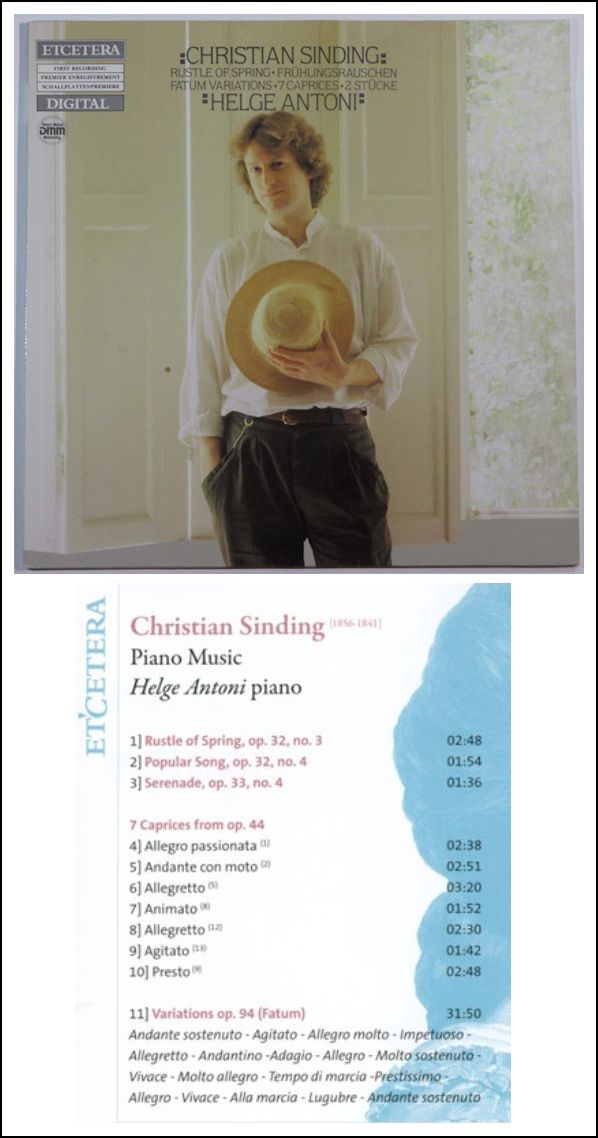

for 4 years. A successful debut at the Mai Musical in Bordeaux led to a much acclaimed debut in Paris at the Salle Gaveau in 1982. The following year he also won the coveted Menuhin Prize. Antoni's creative programming and his personal approach to audiences have made him a much sought-after pianist worldwide both in solo recitals and in concertos with orchestra, including London's Wigmore Hall and St. John’s Smith Square; in The Hague, Philipszaal; in Paris, Salle Gaveau; in Bonn, Beethoven Saal; in Zurich, Tonhalle; in Stockholm, Berwald Hall; in Poland, Chopin's birthplace, Zelazowa Wola (recorded for Polish Television), Chopin Festival in Duszniki, Chopin Institute and Chopin Monument in Warsaw; in Norway, Grieg's house, Troldhaugen (recorded for French Television). In Italy he was the first pianist to have been invited to give an "Hommage to Wilhelm Kempff“ recital in the late master's Casa Orfeo Foundation in Positano; in North America, Kennedy Center Washington D. C., Chicago, Orchestra Hall, and San Francisco, Masonic Hall; in South America, Sociedad Filarmonica, Lima (Peru), and Sala Dorada in Buenos Aires, Argentina. Antoni also enjoys playing chamber music, and has worked with the distinguished sopranos Elisabeth Söderström and Janet Perry, the leading trumpeter Håkan Hardenberger, and the Lysell String Quartet. Antoni has performed extensively on television and radio as a guest artist, as well as presenting his own series. His Classic Video-Clip, one of the first of its kind, has reached a wide audience. He has made several highly acclaimed records for the Etcetera label, including the piano works of Christian Sinding, featuring the famous Rustle of Spring, and the world premiere recording of his masterpiece, Variations Op. 94: Fatum. He has also recorded works by Edvard Grieg, and Rossini's piano works (including several world premiere recordings).

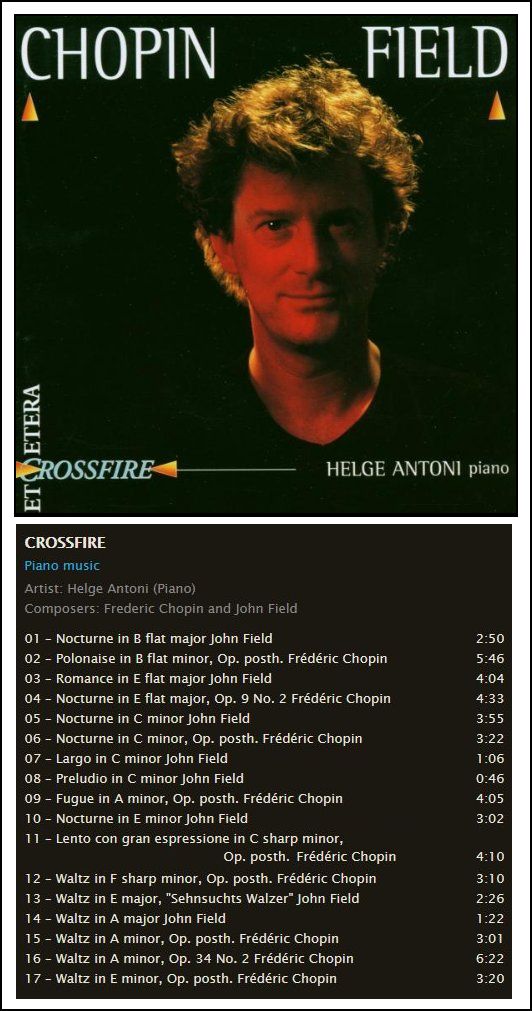

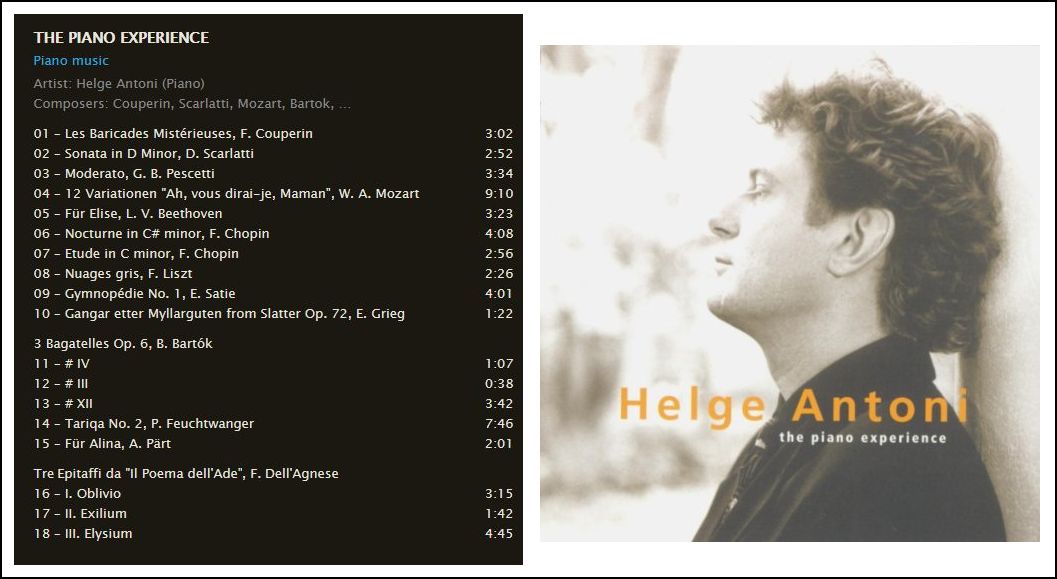

His CD, Chopin/Field highlights influences and parallels between the two composers. His album "The Piano Experience“, on the Swedish label dB Productions, is a recital tracking 300 Years of keyboard music from Couperin to Pärt, with world premiere recordings, and featuring works written for and dedicated to him. The Gramophone magazine said, "ravishingly beautiful ... superbly played with a beautiful singing tone and the most poetic phrasing“. The American Record Guide said, "Antoni's technique is ample, his tone richly colored, and his understanding of the composer's special sound world absolute.“ Antoni has been the Artistic Director of the Late Summer Nights Music Festival in Norway, and the Mozart Festival, as well as the "Concerti al Tramonto“ Festival at the San Michele Foundation on Capri. Since 2002 he is Artist-in-residence at the German University Witten/Herdecke. From 2004 until 2008 he spent large periods every year in Lima (Peru), where he created a Foundation to help young musicians. Antoni lives in Paris, and is an Exclusive Steinway Artist. == Names which are links in this box and below

refer to my interviews elsewhere on my website. BD

|

BD: Once you have made your selections, do you take the

same concert around with you, or do you play many different concerts each

season?

BD: Once you have made your selections, do you take the

same concert around with you, or do you play many different concerts each

season? BD: What advice do you have for composers who want to

write something for you and your particular talents?

BD: What advice do you have for composers who want to

write something for you and your particular talents? BD: Is it nice to come to a city and actually have this

choice?

BD: Is it nice to come to a city and actually have this

choice?

|

He studied at the Royal Academy of Music 1945–1952, was organist and music teacher in Iggesund 1952–1955 and music teacher at the municipal girls' school in Uppsala 1955–1958. He was a music consultant at Stockholm's school board 1958–1961 and curator at Norrköping Orchestra Association 1961–1964. Engström was a music consultant at the National Board of Education 1964–1969, senior lecturer at the Umeå University of Education 1969–1973 and CEO and concert hall manager of the Stockholm Concert Hall Foundation 1976–1986. Engström was elected as member no. 808 of the Royal Academy of Music on February 24, 1977 and was its vice president 1992–1994. Engström has published a large amount of teaching materials for music teaching, including the widely used We make music . After his retirement, he defended his dissertation New Song in the Church of the Fathers , where he examines the use of the Swedish Book of Psalms in 1986 in the Church of Sweden.Hans Åstrand,

born February 5, 1925

in Bredaryd parish,

Jönköping county,

is a Swedish music writer and music administrator. He

studied organ, double bass, and cello; also took courses in Romance languages

at the Univ. of Lund (Licentiate, 1958). He was music critic of the Malmö

newspaper Kvällsposten (from 1950), founder-director of the

Chamber Choir ’53 (1953–62), and founder (1960) and director (1965–71)

of the Ars Nova Soc. for New Music. From 1963 to 1971 he taught music history

at the Malmò National School of Drama, and then was music critic

of Stockholm’s Veckojournalen (from 1976). He served as ed. in chief of the fundamental Swedish musical encyclopedia, Sohlmans musik-lexikon (5 vols., Stockholm, 1975-79). He was a board member (from 1966) and perpetual secretary (from 1973) of the Royal Swedish Academy of Music in Stockholm. In 1983 he was made a prof. and in 1985 received an honorary doctorate at the Univ. of Lund. Åstrand. He also contributed various articles on musicological and general music subjects to many books and journals. [A large philatelic presentation of this event is shown at the bottom of this webpage] |

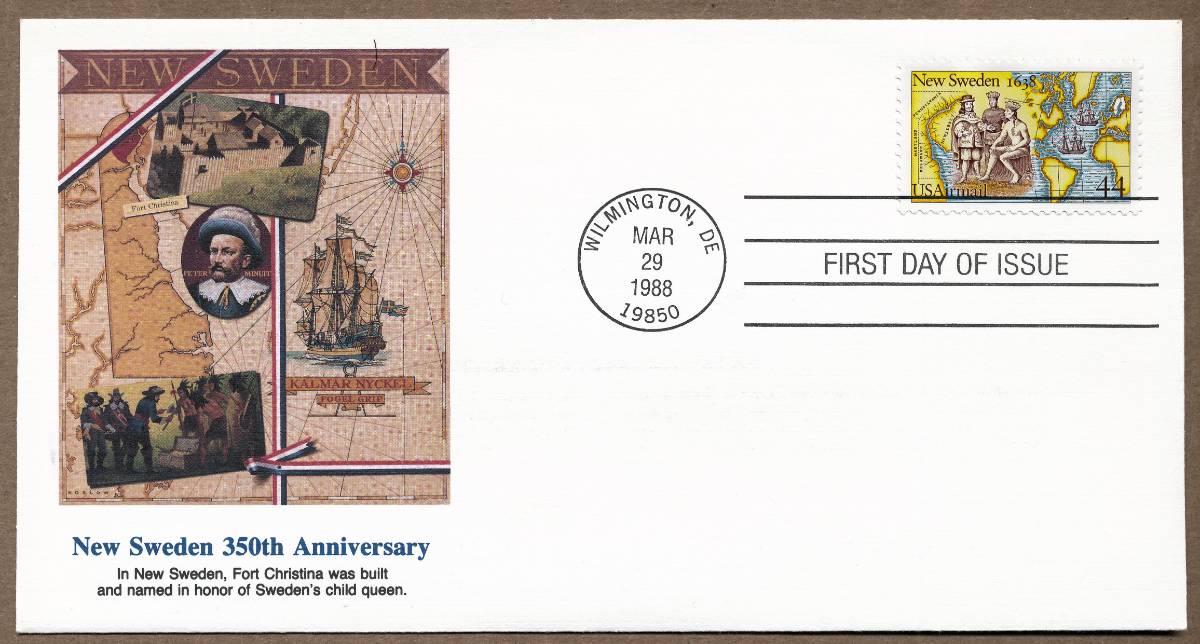

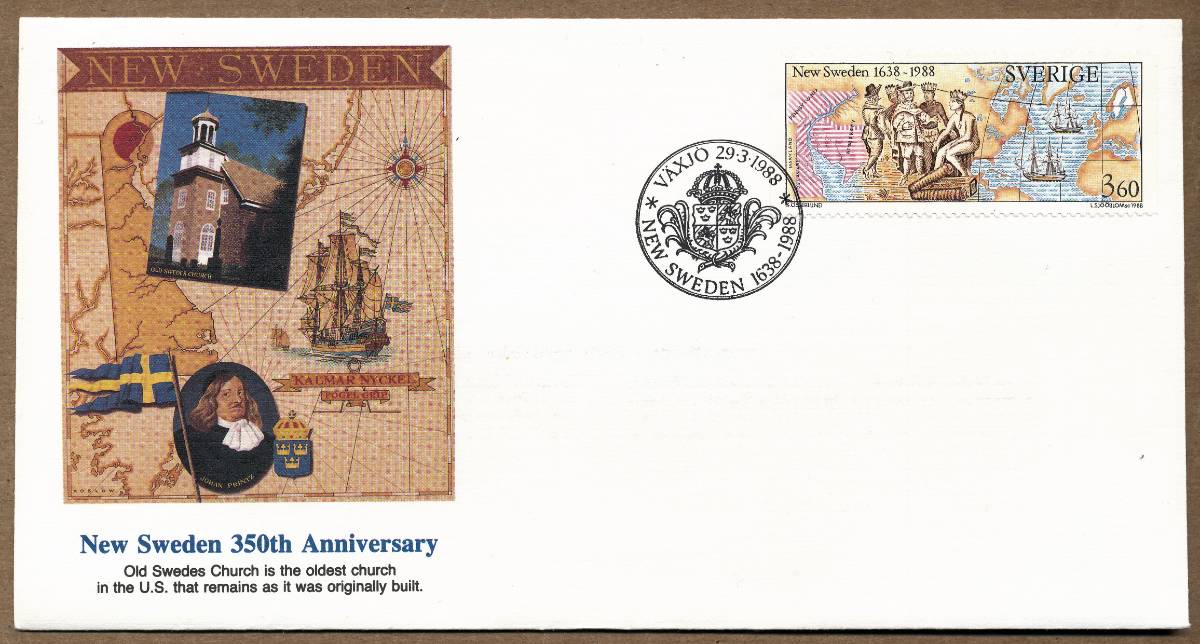

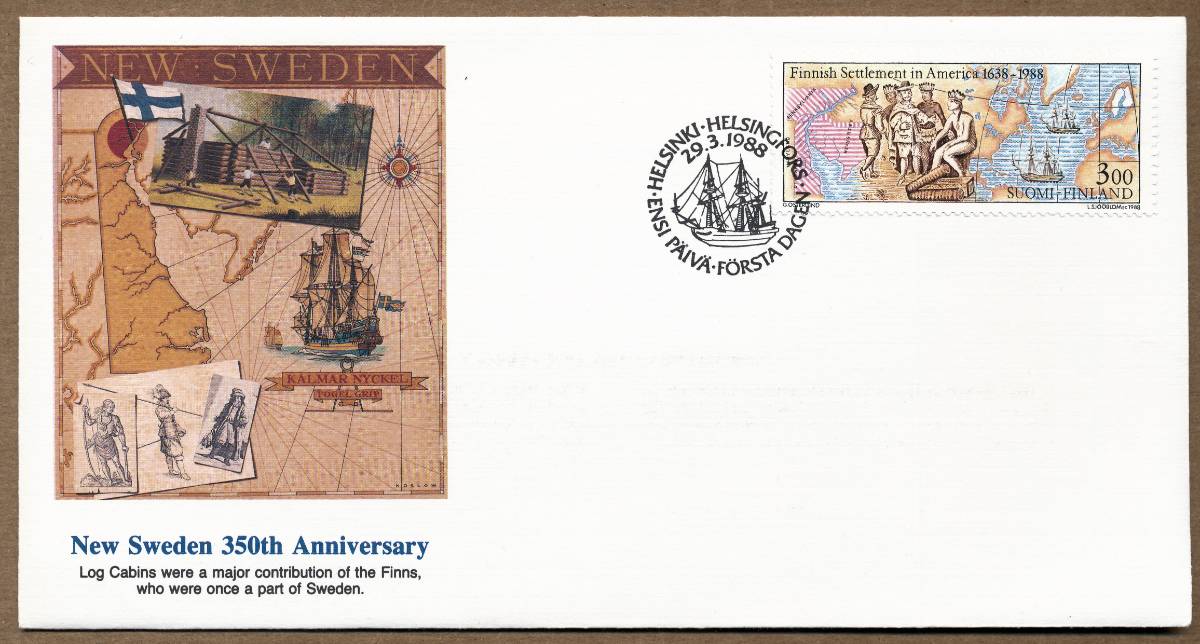

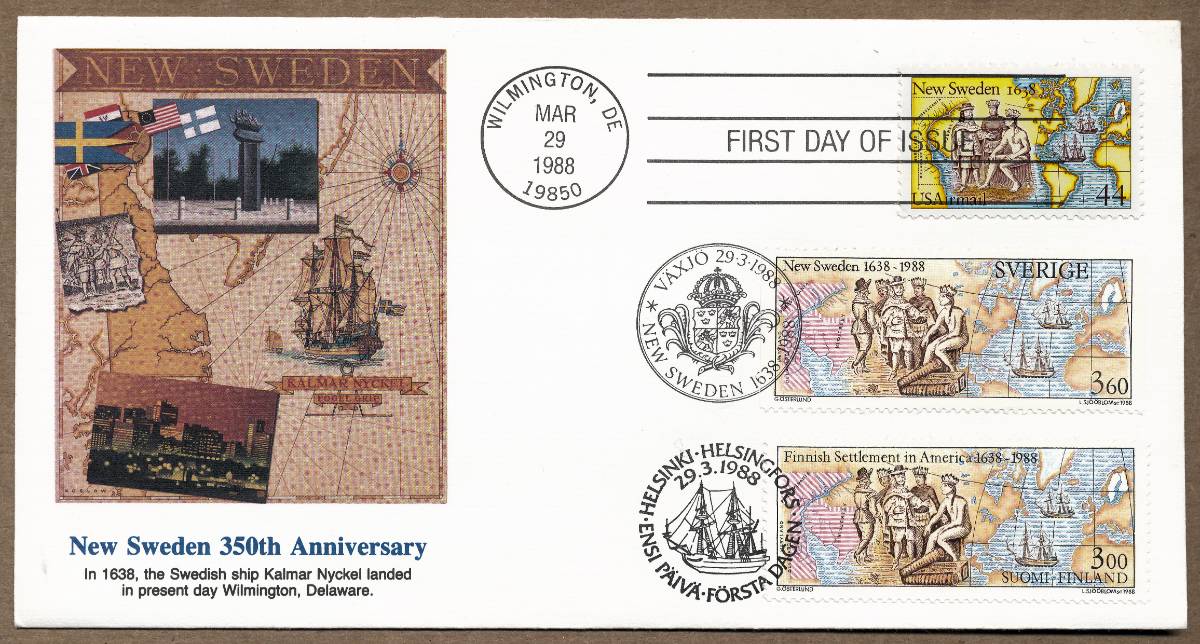

| In 1988, the 350th anniversary of New Sweden

was celebrated with a joint stamp issue involving the US, Sweden and Finland.

New Sweden was Sweden's attempt at colonization in the New World. The

majority of those that came to start and develop New Sweden traced their

roots to Sweden and Finland; it's important to realize that Finland was

a part of Sweden at the time Sweden launched its colonization expeditions. Under the leadership of Peter Minuit, two ships left Sweden in December 1637 bound for the New World to establish New Sweden. The larger of the two ships was the Kalmar Nyckel, with the smaller being the Fogel Grip. The ships arrived in the New World in March 1638, sailing first through Delaware Bay and up the Delaware River, and then up a smaller river that branched off the Delaware River's western shore; the smaller river would be named the Christina River in honor of Queen Christina of Sweden. The colonists landed at a rock outcropping a couple of miles from the mouth of the river in what is today Wilmington, Delaware. From the local Native Americans, the Lenni-Lenape, Peter Minuit purchased the "land from the Christina River down to Bombay Hook" (roughly the northern half of present-day Delaware) and claimed it for Sweden -- it was the start of the colony of New Sweden. In this series there are four First Day Covers, one for the US stamp, one for Sweden's issue and one for the Finland stamp, plus one with all three stamps. The first day of issue for the commemorative stamp program was March 29, 1988 - exactly 350 years after the colonists first stepped ashore on "the rocks" along the Christina River and launched their new colony. The three individual covers were each postmarked in the issuing country, and the joint FDC was cancelled in all three countries.

|

© 1990 Bruce Duffie

This conversation was recorded in Chicago on May 4, 1990. Portions were broadcast on WNIB the following year, and again in 1996. This transcription was made in 2021, and posted on this website at that time. My thanks to British soprano Una Barry for her help in preparing this website presentation.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website, click here. To read my thoughts on editing these interviews for print, as well as a few other interesting observations, click here.

Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM, as well as on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio.

You are invited to visit his website for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.