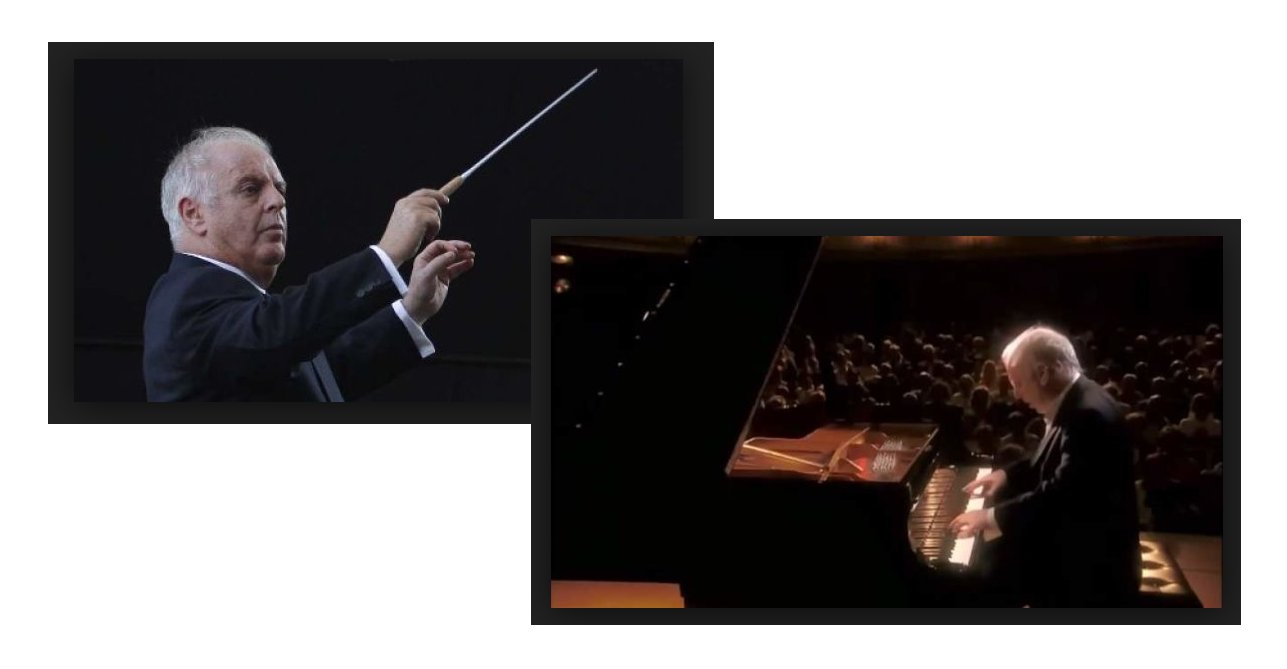

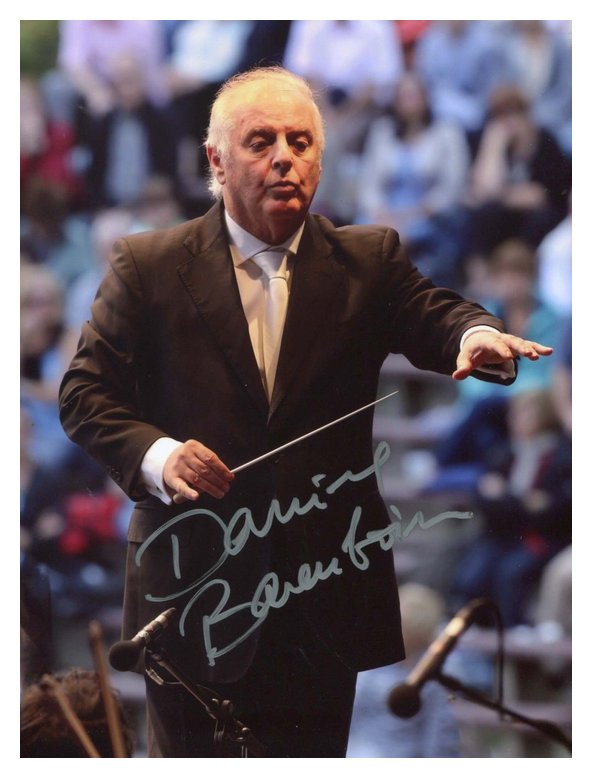

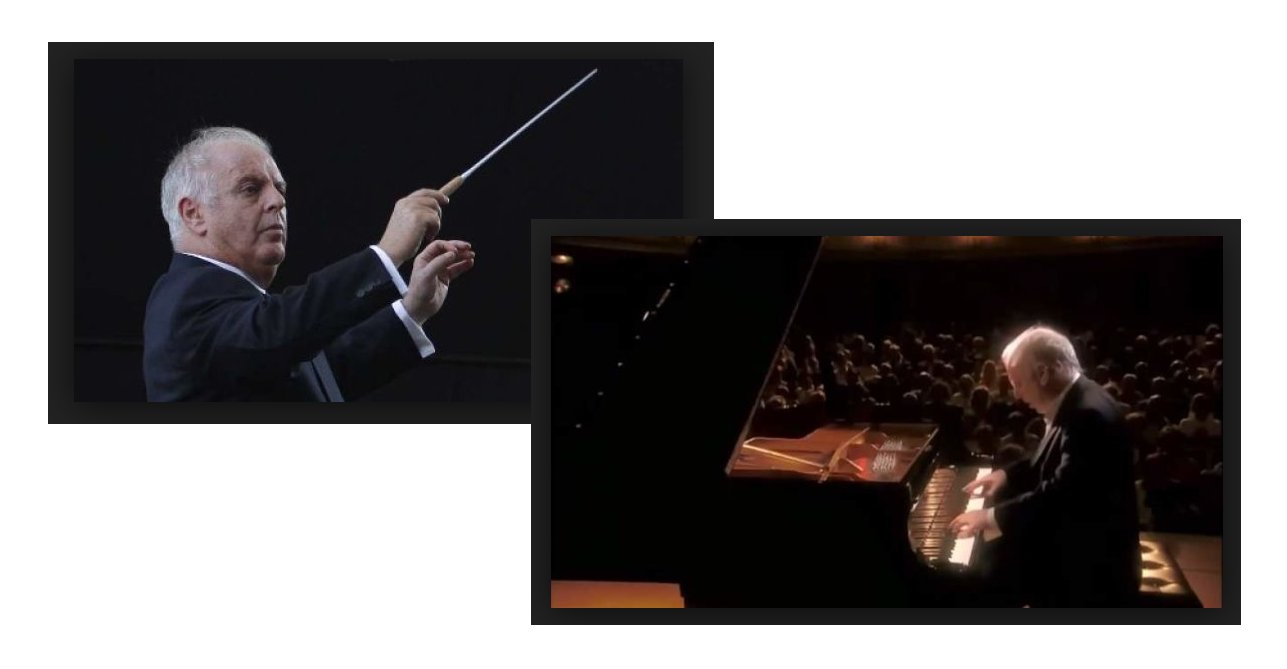

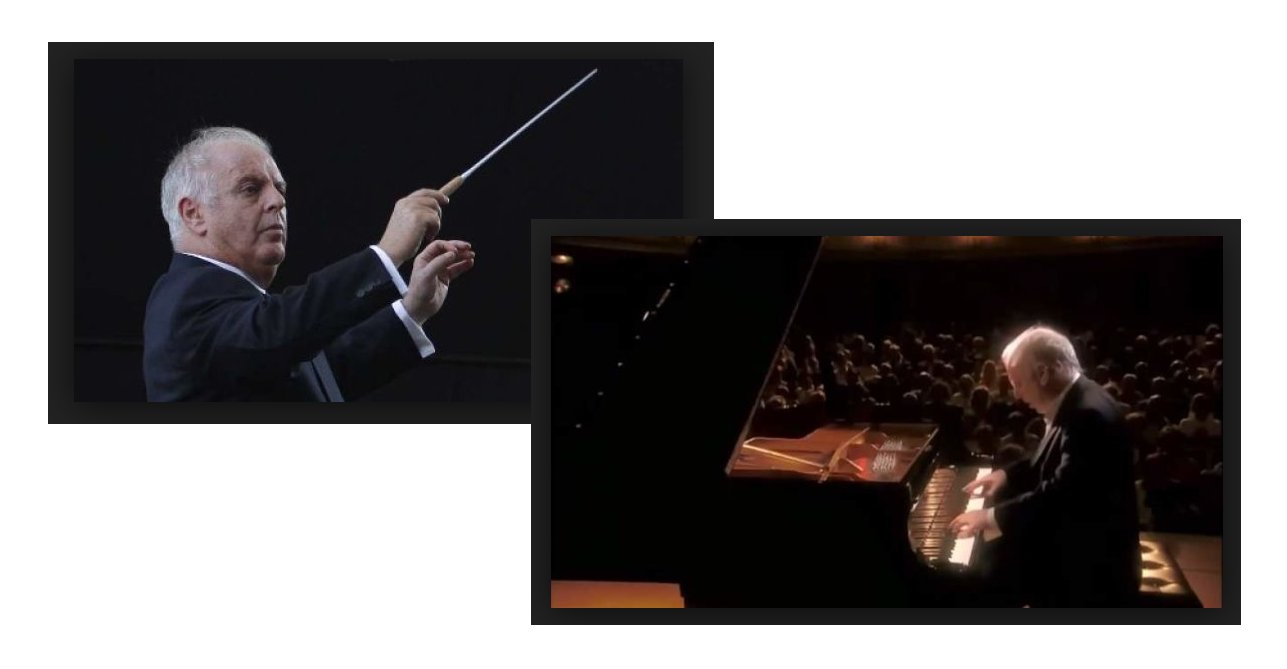

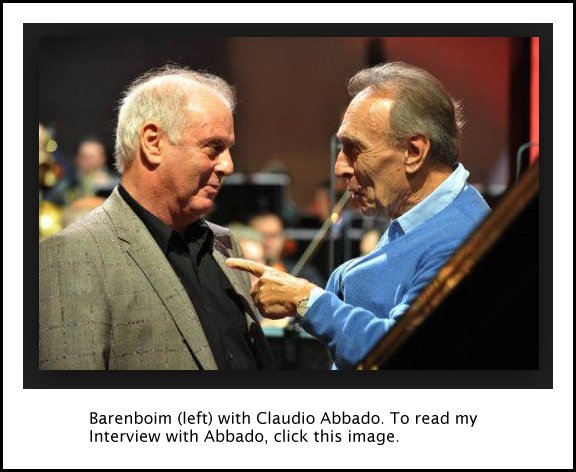

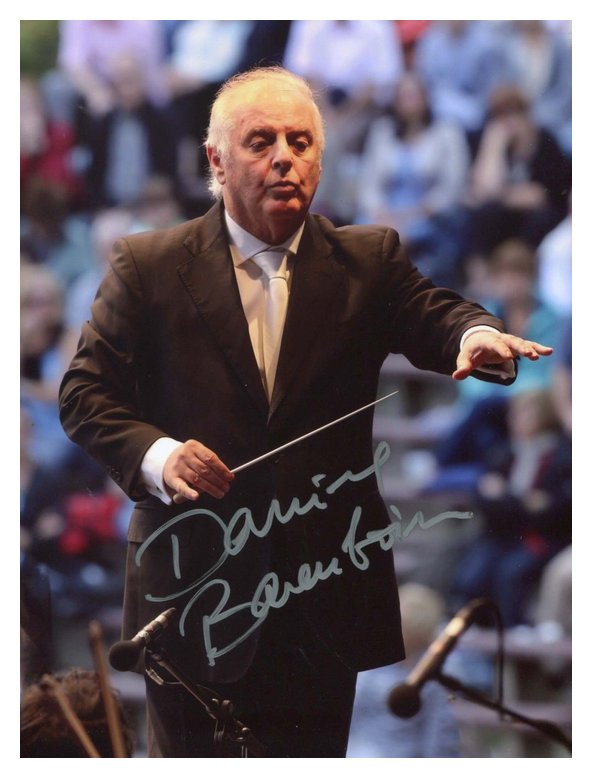

Conductor / Pianist Daniel

Barenboim

Two Conversations with Bruce Duffie

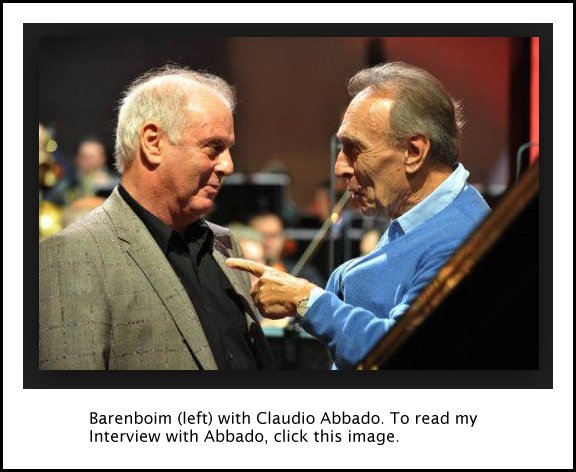

On this webpage are two conversations I had with Daniel

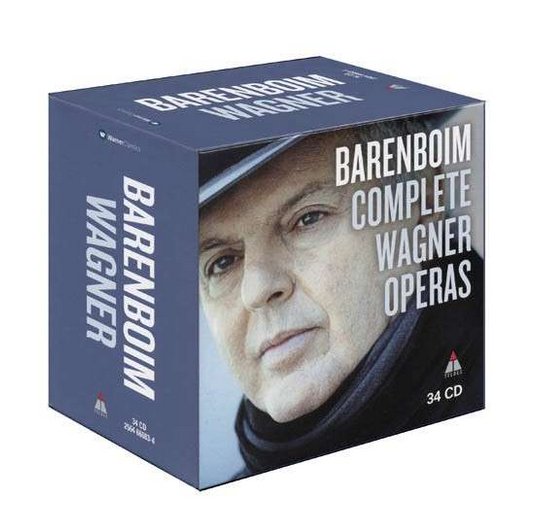

Barenboim. The first was held in November of 1985, when he was

conducting the Chicago Symphony in concerts of Wagner. The second

took place in September of 1993 when he opened the season with the

Verdi Requiem. Material

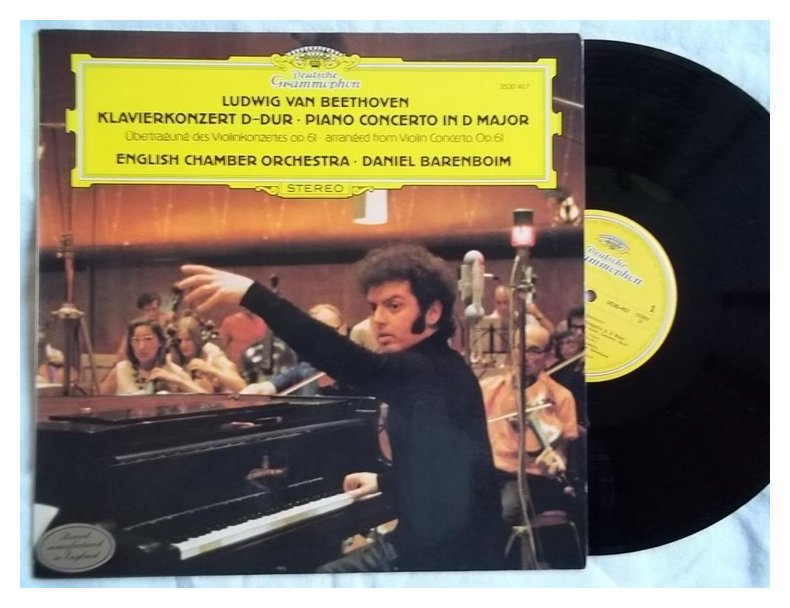

from each interview was used immediately on WNIB, Classical 97 in

Chicago, to promote the concerts, and again at later times when we

programmed his recordings.

The first interview also appeared in Nit&Wit

Magazine in March of 1986, and heralded the appearance of Barenboim as

pianist for the concerts which included the thirty-two Beethoven

sonatas. That interview is presented here slightly edited from

the published version. Photos have been added for the website

presentation. The second interview appears on this webpage for

the first time as a transcription. Throughout this page, names

which are links refer to my interviews elsewhere on this website.

Daniel Barenboim —

Musician

By Bruce Duffie

Nit&Wit Magazine,

March, 1986

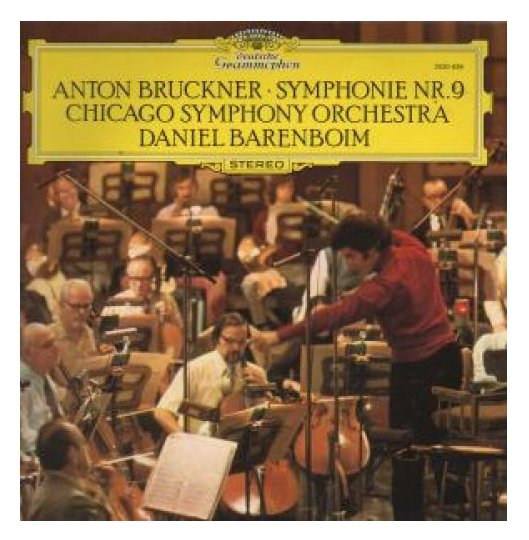

Daniel Barenboim is in demand all over the world for

his musical abilities, and the few places where he performs regularly

are extremely lucky. Chicago must be counted in these lucky few,

for he has appeared here regularly for the last several years with the

Chicago Symphony for concerts and recordings. This season,

Chicago is most fortunate to have Mr. Barenboim at several points in

time, and in several capacities.

The past November, Maestro Barenboim gave concerts

of Wagner. Two performances of the sublime second act of Tristan with cast members from his

Bayreuth production [Johanna

Meier, Rene Kollo, Nadine Denize, and Richard Cohn substituting for

an ailing Hans Tschammer], and two orchestral

concerts containing music of both father Richard and son

Siegfried. It was a weekend not to be forgotten. Now he

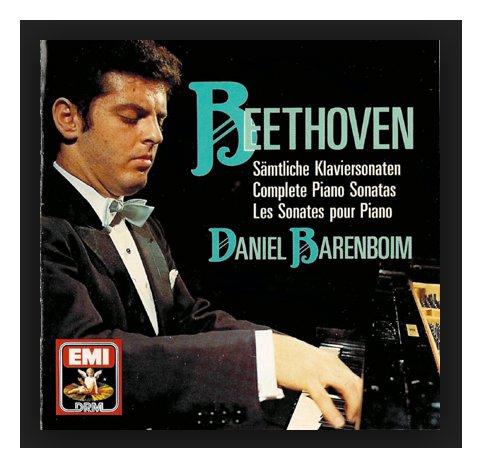

returns to Orchestra Hall in the capacity of pianist to give a series

of concerts containing the complete 32 sonatas for piano by Beethoven.

Earlier this year, when was here for the Wagner

concerts, Maestro Barenboim took time from his very busy schedule to

chat with me about many things. Our all-too-brief discussion

focused mainly on the music he was doing then and now. A portion

of this interview was aired on WNIB last November, but here is the

entire conversation.

Bruce Duffie:

First, tell me about the particular problems and

joys of bringing a stage work to the concert hall.

Daniel Barenboim:

Ha! The joy is that one doesn’t have to

argue with stage-directors who go against the music! I mean this

in jest because I’ve had really wonderful experiences with

stage-directors. The Tristan

which I did in for three years

Bayreuth was with Jean-Pierre Ponnelle who is really the most musical

of stage-directors. But some of the Wagnerian opera acts lend

themselves rather well for concert performance. The second act of

Tristan, the third act of Siegfried, the first act of Walküre are

especially well-suited, although it is always incomplete because there

is no stage, and because they do form a very organic part of the whole

opera. But the main advantage of bringing the second act of

Tristan in concert here, of

course, is the Chicago Symphony. I

don’t think you will find an orchestra in the pit of this quality, and

for me this is almost enough reason. And the singers of Tristan

and Isolde are those who have done it with me for three years in

Bayreuth — really four years including the film

we made of it. So

it has really been worked out with a short time of rehearsal with two

people who have not sung it often onstage together, and with the same

conductor. So I hope that these performances will reflect some of

the joys and sweat that we have put into it.

Daniel Barenboim:

Ha! The joy is that one doesn’t have to

argue with stage-directors who go against the music! I mean this

in jest because I’ve had really wonderful experiences with

stage-directors. The Tristan

which I did in for three years

Bayreuth was with Jean-Pierre Ponnelle who is really the most musical

of stage-directors. But some of the Wagnerian opera acts lend

themselves rather well for concert performance. The second act of

Tristan, the third act of Siegfried, the first act of Walküre are

especially well-suited, although it is always incomplete because there

is no stage, and because they do form a very organic part of the whole

opera. But the main advantage of bringing the second act of

Tristan in concert here, of

course, is the Chicago Symphony. I

don’t think you will find an orchestra in the pit of this quality, and

for me this is almost enough reason. And the singers of Tristan

and Isolde are those who have done it with me for three years in

Bayreuth — really four years including the film

we made of it. So

it has really been worked out with a short time of rehearsal with two

people who have not sung it often onstage together, and with the same

conductor. So I hope that these performances will reflect some of

the joys and sweat that we have put into it.

BD: Now

you’ve done it for these several years. Does it get

better and better for all of you and for the public?

DB: In

Bayreuth it is really unique and it works that

way. The productions get better stage-wise and musically year

after year. Everybody comes to Bayreuth in the summer to do these

performances, and then they work somewhere else during the

season. But when you come back the following summer, at the end

of June or the beginning of July for the orchestral rehearsals, it is

as if the eleven months have not existed because you find yourself in

the same place. After doing the performances and then going away

for the year, when they all come back, they automatically bring back

the last performance. So you start rehearsing in the second year

where you left off at the last performance of the first year, and so

forth and so on.

BD: Is that

due to the performers, or to the atmosphere, or

to Wagner, or what?

DB:

Everything. I think a bit of everything, but they are

first-class musicians who work elsewhere during the year.

BD: Do you

find that the covered orchestra in Bayreuth is a

particular help in Wagner, or would that be a good idea in all opera

houses?

DB: I think

it would be a good idea in many operas, but not in

everything. I would hate to play Don Giovanni or Così Fan Tutte with a

covered pit. But I feel that many other

operas which were not thought of like that could only profit.

BD: Even in a

Mozart opera, such as the two you mentioned, where you’re using an

orchestra that

is twice or three-times the size that Mozart had?

DB: Yes. The

thing about the covered pit in

Bayreuth is not just a question of volume. There, the whole sound

— both orchestra and singers — gets

blended before it comes out to the

audience. So anything that requires great transparency and

articulation is not really adaptable for that.

BD: When

you’re conducting an opera, how much do you get involved

with stage-direction, stage-mechanics, etc., or are you just involved

in the music?

DB: Oh no, if you

really want to do an opera well, you can’t be

involved just with the music. The stage problems can only be

solved hand-in-hand with the music. Some of them can be solved

only

through the music, and vice versa. There are a lot of musical

problems with the singers that can be solved stage-wise.

BD: How do you see

Tristan as an opera, as a

piece?

DB: [Laughs]

I don’t think you have enough time on this radio

interview for me to tell you. It’s impossible to tell you.

BD: Is it a

turning-point in music history? Does

everything that comes after it look back to Tristan?

DB: I’ll tell

you something. When I did Tristan

for the

first time in Berlin, before I went to Bayreuth, for a long

time — maybe six, seven, eight months

— I looked at all other music

through the eyes of Tristan,

even music that was written before,

not only after. The piece is so catalytic. It’s not

just that one single chord. That chord, by the way, did not

originate with Wagner. It appears first in a song by Liszt.

But

it is the whole relationship of chromaticism and volume and density of

the orchestral writing which is so different. What Wagner

does for the orchestral musician or a conductor is that it sharpens all

your expressive tools to the maximum. You

need everything in Tristan.

You need the ability to play the most

beautiful, sustained legato,

you need the ability to play extremely

clear and articulated marcato,

you need to be able to play soft

accents, hard accents, to play super pianissimo,

to play super

fortissimo, everything

absolutely to the limit of human

possibility. I also find it extremely useful for every other kind

of playing.

BD: Is Wagner in

and of itself harder or more difficult to play

than any other composer?

DB: No.

Everything is difficult in relation to your real

knowledge of it. Many things seem very hard to people who only

work intuitively. The same difficulties become less so when your

knowledge is in depth and becomes conscious knowledge. In other

words when you know how it is made, not only how it sounds, then the

degree of difficulty changes. Some things remain difficult no

matter how much you know about them.

*

* *

* *

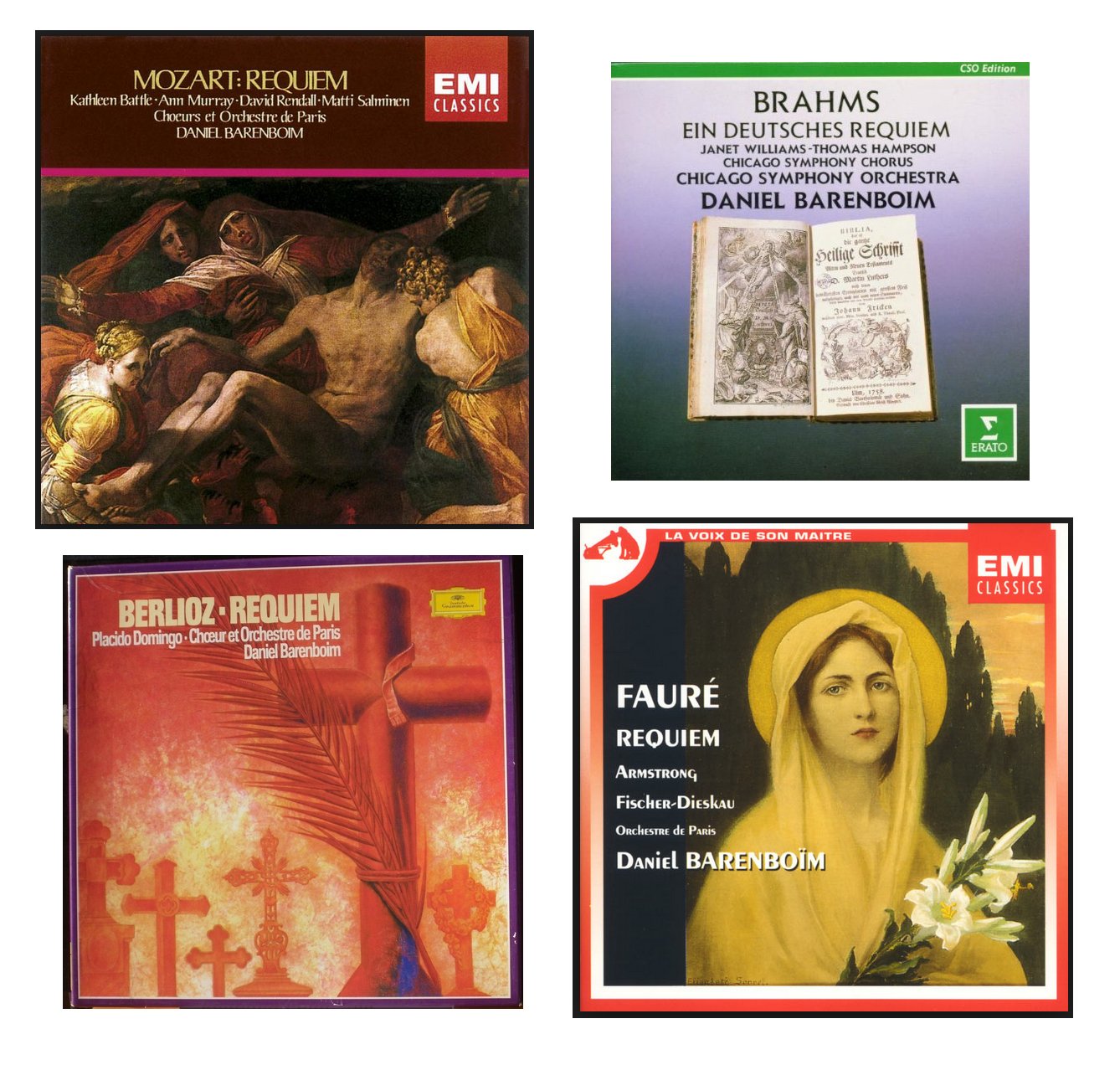

BD: You’ve

made a number of recordings. Do you feel

you’re competing against your own record when you perform?

DB: No, I never

hear my own recordings. I have absolutely

no interest in them. Once they are made, for me they are a thing

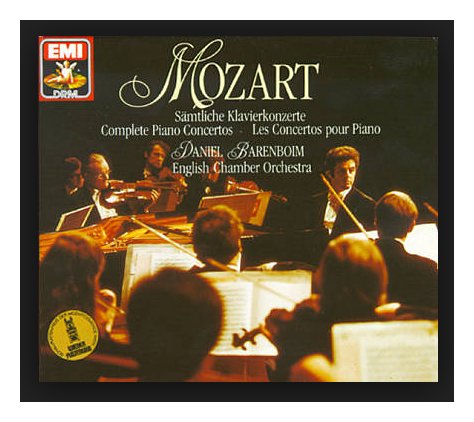

of the past. The only time that I have sometimes listened to old

recordings is when I have replayed some of the Mozart concertos, and

some of the cadenzas were my own and I didn’t write them down.

But that is for a specific reason. I certainly would never dream

of sitting at home on a free evening and listen to my own recordings.

DB: No, I never

hear my own recordings. I have absolutely

no interest in them. Once they are made, for me they are a thing

of the past. The only time that I have sometimes listened to old

recordings is when I have replayed some of the Mozart concertos, and

some of the cadenzas were my own and I didn’t write them down.

But that is for a specific reason. I certainly would never dream

of sitting at home on a free evening and listen to my own recordings.

BD: Would you

sit at home on a free evening and listen to someone

else’s recordings?

DB:

Hardly. I’m not a great record-listener.

BD: Is it a

mistake for such a large segment of the public to be

great record-listeners?

DB:

[Hesitating] I don’t know. As long as one keeps

in mind that a recording is really second-best, and it will never

replace live music. As much as I admired and respected him, I

can’t agree with Glenn Gould or his philosophy. You can’t say

that it’s an artificial way of making music, but it is an artificial

way of reproducing music. Music is not really reproducible.

It only has a reason for being from this moment to that moment in this

place and not elsewhere. A whole lot of physical considerations

come into being which are not there. When we play the second act

of Tristan in Orchestra Hall,

we automatically but also consciously

play differently than if we were in the pit at Bayreuth or in another

hall. We adjust the acoustics to the sound of Orchestra Hall and

to the degree of reverberation, etc. So when you record in

one studio and then listen to the disc on another machine in another

room, nothing is really as it should be. If I were playing the

same piece in your living room, I would probably play it at a

completely different tempo. Therefore it is a very bastardized

way of doing music, and a bastardized way of listening to music.

BD:

[Mischievously] Then why do you make so many recordings?

DB: Because

I’m probably weak and people ask me to do it and I do

it... certainly not for artistic reasons.

BD: Does it bother

you, then, when someone comes says they enjoyed your recordings of this

or that?

DB: No, I’m very

happy that people enjoy what I have done,

obviously.

BD: Is there the

same artificiality in film — your Tristan film,

for example?

DB: The Tristan film was made during

performance. The

performance was filmed, so it is not like the Don Giovanni of

Joseph Losey, or a regular cinematic film. Being a film of a

performance, I suppose it has a degree of faithfulness that it wouldn’t

otherwise. I’m not so keen to see filmed opera, even though

they’re very impressive in many ways. I simply cannot get used to

things like the reverberation of a studio while they are singing in the

open air, or when the person gets further and further away in the

perspective, but the voice gets louder and louder and louder. I

can’t, frankly, come to terms with this artificiality. But, if

this really gets more people in the opera house and gets them

interested in music, fine.

*

* *

* *

BD: Tell me the

secret of performing

Mozart... or is this another six-hour question?

DB: [Laughs] No,

this is not a six-hour question, it is an

impossible question. I don’t think there is a secret about

it. It is stylistically very difficult. It is so complete

that it doesn’t allow any underlining. This is what is so

difficult. In other words, when you play a phrase of Tchaikovsky

or Wagner or Brahms, or even of Beethoven, you can

underline certain elements or certain notes in the expression. In

Mozart there are always ten or fifteen or twenty different expressions

going on at the same time, and each one must have its own purity and

its

own independence. Mozart does not tolerate this kind of

underlining. The minute you start to make a point, you are

through with it.

DB: [Laughs] No,

this is not a six-hour question, it is an

impossible question. I don’t think there is a secret about

it. It is stylistically very difficult. It is so complete

that it doesn’t allow any underlining. This is what is so

difficult. In other words, when you play a phrase of Tchaikovsky

or Wagner or Brahms, or even of Beethoven, you can

underline certain elements or certain notes in the expression. In

Mozart there are always ten or fifteen or twenty different expressions

going on at the same time, and each one must have its own purity and

its

own independence. Mozart does not tolerate this kind of

underlining. The minute you start to make a point, you are

through with it.

BD: Is all this

complexity what makes it such that it will never

die?

DB: Probably.

BD: Are there

other composers who are like that?

DB: Like

Mozart? No. For me, it is a unique

phenomenon.

BD: You’ve done

the symphonies, the piano concertos, and the

operas. How are they different or similar?

DB: Many of the

great piano concertos are very operatic in

nature. The finale of the E-Flat

Concerto, #22, could be out of Figaro.

Some of the Da Ponte operas are

as intimate as chamber music, and they are very much

connected. Therefore I think that the best performances of the

operas are the ones which have the chamber music like quality about

them, and the best performances of the piano concertos are the ones

that have an operatic taste about them.

BD: So they all

relate together out of the mind of Mozart?

DB: That’s right.

BD: Are the best

performances of Wagner like

chamber music, or are they like symphonic works?

DB:

Everything. The most terrible thing is this accepted

pre-conceived idea of the fat, loud, Wagner sound. This is only

one side of Wagner. So much of it is extremely delicate and

extremely transparent, and, if you want, extremely

chamber-music-like. One of the most important things in a Wagner

performance

is really balance. The minute you start balancing so

that one can hear more of what is important, then suddenly everything

becomes more transparent and at the same time richer.

*

* *

* *

BD: Let me ask about

Beethoven. You’re going to be

presenting all thirty-two sonatas. Do they belong together as

a unit?

BD: Let me ask about

Beethoven. You’re going to be

presenting all thirty-two sonatas. Do they belong together as

a unit?

DB: Well, they

were not conceived as a unit, obviously, but they

give the most complete picture of Beethoven, more than the nine

symphonies. The most complete picture of Beethoven that you get

is in the piano sonatas and the string quartets. It is not the

same

in the Mozart piano sonatas. They don’t really give you a

complete

picture of Mozart. You have to go to the piano concertos or the

operas for that. But every aspect of Beethoven is

there. Again, as with Wagner, there are always pre-conceived

ideas. When you say “Beethoven,” people immediately think of the

Eroica or the Fifth Symphony, all the obviously

more dramatic

pieces. But the less dramatic pieces are just as much part of his

nature.

BD: Composers go

in and out of fashion. Is the public right

in its taste dictating that they’ll have more Mozart or less Mozart,

more Wagner or less Wagner, more Beethoven or less Beethoven?

DB: I don’t know

that the public really dictates that.

There are some composers that have always been in fashion. At

least

from the moment that they became in fashion they have never left that

place. In the case of Mozart, in many countries he was accepted

very late. But in that respect, Mozart and Beethoven are

absolutely above all possibility of fashion.

BD: Is there any

kind of musical line that goes from one composer

to another over the centuries?

DB: Wagner would

have been impossible without Beethoven,

and Beethoven would have been impossible without Mozart. But if

you think of a line, then you must go Mozart, Beethoven, Schubert,

Weber, Wagner... Schumann, also, even

Liszt. It is all very connected. The only composer

historically speaking who is unnecessary is Brahms. I’m not in

any way meaning that the music is any less beautiful or less important,

but historically speaking, if Brahms had not existed, music today would

be exactly the same. Maybe Schoenberg was the only one who was

influenced in any way by Brahms, but otherwise absolutely not at

all historically speaking. Mendelssohn is the same

thing. If Mendelssohn had not existed, the history of music would

be exactly the same. We would be a lot poorer. Don’t

misunderstand me. I’m not saying that they didn’t write beautiful

music. In the same way, historically speaking, Debussy is one of

the most necessary composers. In fact, after Wagner, probably the

most

necessary composer is Debussy. The whole of the twentieth century

could not

exist without him. Stravinsky could not exist without Debussy;

Bartók, also,

and Webern.

BD: Is there any

composer who is living now who is absolutely

necessary?

DB: The more of

his works I do, the more I am taken by a lot of

music by Pierre Boulez.

Whether it is of that historical

importance I don’t know. I think we need more distance in time,

probably, but he certainly writes very impressive and touching music.

*

* *

* *

BD: You’ve made a

recording of Il Martrimonio Segreto

by

Cimarosa. Why is that work not more well-known?

BD: You’ve made a

recording of Il Martrimonio Segreto

by

Cimarosa. Why is that work not more well-known?

DB: I don’t

know. I think it’s a lovely opera and I really

enjoyed doing it.

BD: Whenever we

play it on WNIB we get calls asking if it’s

Mozart. Is that a mistake to think it’s by Mozart?

DB: No. It’s

so Mozartian in character.

BD: Are there any

composers in the “standard repertoire” who

really shouldn’t be there?

DB: I think that’s

what very much a matter of taste.

BD: How do you

balance your career — opera/concert/solo

recital/chamber music?

DB: Basically, I

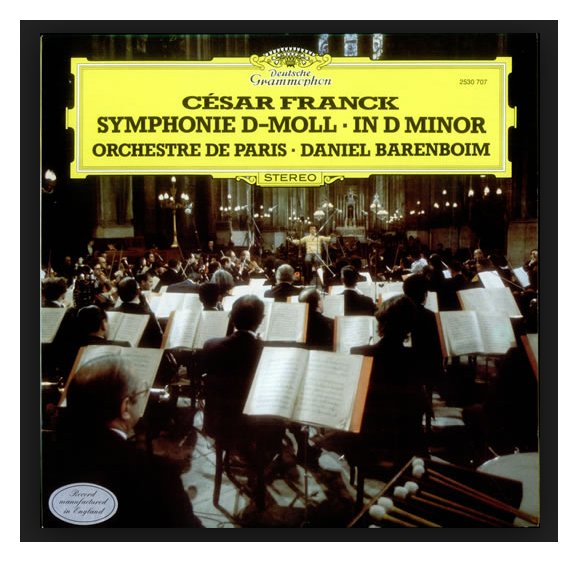

don’t guest-conduct. I come to Chicago,

certainly not as much as I would like to. I would be much happier

coming more, but I simply can’t. I can’t multiply myself by

four. I don’t want to give up playing the piano, and I enjoy very

much my work with the orchestra in Paris. I’ve been there ten

years and I find it extremely satisfying. And I like to do

more opera. Those are my three priorities. Other than that

I

come here a little, and I go to the Berlin Philharmonic a little.

Those two orchestras are very close to me musically and humanly.

And that’s all.

BD: You say you’d

like to do more opera. How do you decide which

operas you will conduct?

DB: I was asked to

do the new Ring in Bayreuth

and this is

something that I am greatly looking forward to.

BD: How does that

present more problems than Tristan?

DB: [Laughs]

I will tell you after I’ve done it!

BD: Does opera

work in translation?

DB: Some operas

do, others don’t. I must say that I

worked last year for the first time with the “surtitles” which are so

popular here in America. We brought the Paris production of

Figaro to Washington D.C., and

it was extremely well done and an

extremely positive solution to the problem. I thought that the

audience really enjoyed the text much more so than normal.

BD: Thank you for

coming to Chicago, and for spending so much

time this season.

DB: Thank you.

Almost

eight years later we met again and had another conversation . . . . . .

. . .

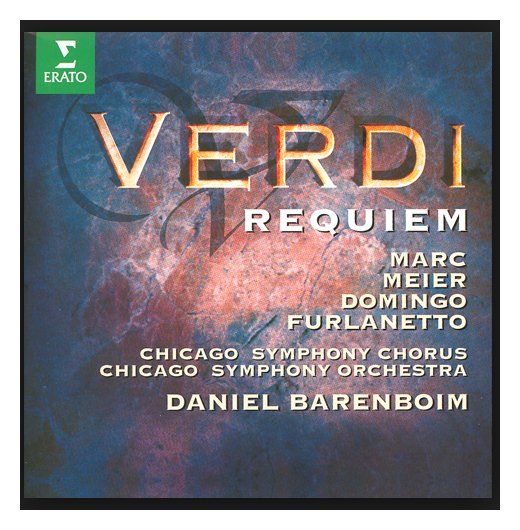

BD: Let

is talk a little bit specifically about the Verdi Requiem to use on the air

tomorrow. Then I hope we can speak a bit about music in general?

DB: Whatever

you want!

BD: Very

good. [Starting the segment for immediate on-air use] I’m

speaking today with Daniel Barenboim, the Music Director

of the Chicago Symphony Orchestra, who is about to begin the brand new

season with the Verdi Requiem.

First, tell me the joys and

sorrows of combining the orchestra with the human voice.

DB: The basis

of all music is, really, the

human voice, because it obviously comes from the actual body, and not

from an outside instrument. This is why many things are more

difficult for singers. If

a pianist is nervous, upset, or tired, the piano is the instrument and

still stays in spite of that, whereas the slightest difficulty or

discomfort shows itself in the human voice. But real

expression, where music really comes from, is the human voice, and

everything else is... I wouldn’t say an imitation, but it’s a further

development of what the human voice can produce.

BD: Is this

why in rehearsals you would

say, “Use a singing line?”

DB: Probably,

yes.

BD: If there

is a bit of tightness or nervousness in the

throat, is that in any way the conductor’s responsibility, or is it

merely the singer’s responsibility to overcome as a professional?

DB: A

conductor can be of great help to

a singer in a situation like this. You can’t completely cure

certain things, but a conductor can be of great use, in both musical

and psychological or human help to a singer.

BD: You’re

doing the Verdi Requiem

to open this season. It’s sometimes been called Verdi’s greatest

opera. Do you agree with that?

DB: Yes and

no. It is a very theatrical

piece, but it is not really an opera. There is a difference from

a piece being theatrical. Actually, the Mozart Requiem,

for instance, is also theatrical in its own way, in its own style,

whereas the Brahms isn’t, or the Fauré isn’t. In

that respect, Verdi is, but it is the combination of

the theatricality with the religious content that make the Verdi

Requiem such a special piece.

BD: Is that

at all because Verdi and Mozart were men

of the theater, whereas Brahms, and to a lesser extent,

Fauré were not?

DB:

Probably. With Brahms it’s

also the fact that it is a different text. Although

it’s called a Requiem, as you know, it’s not the Catholic Mass.

It is the

protestant music, and takes a lot of the text from the Old

Testament. But it’s very interesting to compare the

real Catholic requiems of Mozart, Verdi, and

Fauré, and how they dealt with the different concepts

— what the fear

of God meant for one, and for the other was almost a relief, and the

feeling of good, etc.

BD: Yet

there’s really not a religious quality

to it because members of all religious denominations and sects can

enjoy it.

DB: Oh, of

course. The Verdi Requiem

is probably one of the most universally

accepted works of music imaginable, and fits almost any special

occasion. It doesn’t have to be only an occasion of sadness or

of tragic circumstances. It is an expression of man’s position in

this world in relation to his or her creator, whoever that may be, and

as such it is a piece that

speaks to everybody.

BD: We’re

talking a bit about the text. In

an operatic piece, we talk about the balance between the music and the

drama. Does that shift at all for the Verdi Requiem, being a

sacred text?

DB: I don’t think

so. The main principles of putting together text and sound are

just as evident in the Verdi Requiem

as they are in opera.

DB: I don’t think

so. The main principles of putting together text and sound are

just as evident in the Verdi Requiem

as they are in opera.

BD: You do

this in one piece, just as a complete

work without any intermission?

DB:

Yes. Apparently, when Verdi conducted it, I

think it was in Paris, they did an intermission after the “Dies Irae,”

but I think it really loses the tension that can be, and should be

accumulated by performing it without an intermission,

without a break. If I’m not mistaken, this was the

only occasion when Verdi conducted with a break. Any other

times it was done was without stopping.

BD: Is there

anything at all that should

go with this work, or should it stand completely alone on a concert?

DB: Oh, it

must stand alone. From

beginning to end it should really fill the evening, the day, for the

performer and for the listener.

BD: As Music

Director of the

Chicago Symphony, do you make sure that there are several great big

choral works of this stature in every season?

DB:

Yes. We are very fortunate that we

have such a wonderful chorus in Chicago, and we have to take advantage

of that. The most wonderful thing about it is that a

chorus has been attached to the orchestra for so many years, and

therefore there is a unanimity of style, a homogeneity of style that

you cannot get with other choruses. You can find

wonderful choruses, but when they work regularly with the same

orchestra they get used to the same sound and the same kind of

articulation and color in the music. This chorus and this

orchestra’s had the good fortune to work together with the same chorus

and with Margaret

Hillis for so many years. It

is a very unusual situation for a great orchestra to do that. I

know that we are also, from this point of view, the envy of

many great orchestras who do not have a chorus attached to them, and

have to always import one, including the Berlin Philharmonic.

BD: You rely

on Margaret

Hillis to train the chorus, and she is about to retire. Are you

looking for someone who will carry on her

tradition, or are you looking for someone who brings something new?

DB: Those two

things are not incompatible. It has to be somebody who

understands what Margaret Hillis

has been able to create here and develop and therefore continue in

this line, and also have something of his own to say, not just an

imitator.

BD: When

you’re working on the big choral works,

do you collaborate with the choral director, or do you expect him or

her to prepare the chorus and then let you finish shaping

the sound and the idea?

DB: It

depends on the piece. I’ve

worked for so many years now with Margaret that there’s almost no need

for me to even meet with her before and discuss. If

there is something special, then obviously we do, but it is

very much a real collaboration. It can only be that way.

The

idea that the chorus director can prepare the piece so that any

conductor could deal with it — in other words,

so that the notes are

there and the dynamic is there and the pitch is there — doesn’t

really

work. Musicianship and phrasing is not like the cream that you

put on top of the cake. You don’t add it. If you prepare a

work in a purely mechanical way,

it’s impossible to then do it musically. It can only

work if the choral director is in sympathy with the conductor of the

evening, and vice versa.

BD: So you

want the choral director to have a bit of input in terms of

interpretation and feeling?

DB: Of

course, yes.

BD: Is it a

little bit easier because

the Verdi Requiem has been

sung here a number of times, or would it be

easier if this were a brand new work that you were shaping from the

beginning?

DB: I don’t

know. Some works that have been

done have been easier because they have been performed,

and others because they haven’t. It depends very much on the

piece.

BD: Is there

any ambiguity at all in

opening the orchestra season with a big choral work rather than a big

orchestral work?

DB: I don’t

think so. The

great choral works, like the Verdi Requiem,

are very festive pieces,

and they fit a very festive occasion, which is the

opening of the season. Therefore, it is absolutely

right to do it with the Verdi Requiem,

as we are this year.

*

* *

* *

BD: You have

a number of rehearsals

before the concert. Is all your work done in rehearsal, or do you

leave something for that spark of the evening?

DB: Oh, you

have to leave a lot for the evening, but

what you leave for the evening doesn’t work unless the actual

preparation has been done. You can’t just play it through and

then really make

the performance in the evening. The more you rehearse and prepare

in detail, the more freedom you will have in the evening. If you

don’t prepare, then it is very much a

question of pure luck, and that it shouldn’t be.

BD: Even with

an orchestra such as this, that is

supposed to be so very fast?

DB: That has

nothing to do with the quality of the

playing. That has to do with the quality of the music-making and

what you do with it.

BD: You don’t

need to mention specific times, but have there been any performances

which you felt were perfect?

DB: No.

No, I don’t think this

perfection exists. We have such a strong feeling that we have to

conserve everything. We are very much

a sort of a society that keeps records, and are very much interested in

the past and what has become, and music is not like that. Music

is not to be conserved, and not to be preserved. I don’t think

that it can be. What is so special about a special work on a

special evening is not something that can be preserved, and is not

something that one should attempt to do. Therefore, the

word “perfect” doesn’t exist. It was right for that particular

evening, in that particular acoustic, in those particular circumstances.

BD: So it’s just the

performances that

should not be preserved but the music and the inspiration

should be?

BD: So it’s just the

performances that

should not be preserved but the music and the inspiration

should be?

DB: Of

course, of course.

BD: Then each

time

you’re really starting from nothing, without any kind of background at

all?

DB: No, not

from nothing because there has

been a lot of work of preparation being done. But in the actual

act of

creation, of course you start from nothing. The Beethoven Fifth

Symphony doesn’t exist now as you and I are talking. It

doesn’t

really exist, and all these records that exist in the shop are not

it. Beethoven’s Fifth

will begin to exist again the moment an

orchestra somewhere plays the first note of it and goes on

playing. Then it comes to life.

BD: Does it

begin to exist the moment the record

begins to play?

DB: I don’t

think so. I don’t

think the record can capture the very essence of the music. It’s

a document of a certain

performance, but no more than that. There cannot be what the

public and critics sometimes want to hear, which is a definitive

performance. It doesn’t exist.

BD: But it

could be definitive for an evening?

DB: Yes.

BD: Do you

want every evening to be

definitive for that evening?

DB: That is

an impossible situation.

BD: Well,

we’ve been dancing around it, so let me hit you with a great big

question. What is the purpose of

music?

DB: Why does

music have to have a purpose? What is the purpose of having a

symphony orchestra?

What is the purpose of having a concert? That question I can

answer relatively easily. The music is there to provide happiness

or solace to people who are in difficulty, but that is not really what

music is about. Music is neither

descriptive, nor does it have a purpose. Music doesn’t become

something. Something can become music, which is a very different

thing. Sound can become music, provided they are put together in

such a way that they relate permanently to each other, and influence

each other permanently. Then it becomes something, but it

doesn’t have a purpose as such. It can be used for many things by

people. It can be used for all sorts of

motivations, but that is not the nature of music itself.

BD: So sound

is not music until it is put together?

DB: Sound is

only the language, the means by which

music can express itself.

BD: John Cage was saying

that all sounds are music, even if they are random.

DB: I don’t

believe in that. I believe that the

organic element, the feeling of organic belonging to each other, of

unity of the sounds is what makes music.

BD: So

where’s music going today?

DB: If only I

knew! We are in a difficult

period about development of music, and have been for a long time

now. So many

people who go to concerts regularly and who have a certain

closeness to music still think of music written in the beginning of

this century as modern music. They think of Schoenberg. A

lot of people will tell you the Schoenberg Gurre-Lieder — maybe not that

piece, but some of the Webern pieces — all this

is

modern music. We are now at the tail end of this century, and

these were written between 1910 and 1920. If you transport this

century back, I don’t think for

one moment that people in 1893 thought of late Haydn symphonies or

middle Beethoven

symphonies as modern music, which is the equivalent in the number of

years.

BD: Were they

thinking of late Tchaikovsky and

Dvořák and even Puccini as their moderns?

BD: Were they

thinking of late Tchaikovsky and

Dvořák and even Puccini as their moderns?

DB:

That was their modern music. I don’t know whether it has to do

with the

break in tonality and that so much music after Wagner and

Mahler went into the atonal system, or whether it has to do with other

phenomena, the fact remains that there is a

very unhealthy state of affairs. Not only the

public, but so many musicians exist

today who spend their whole life with a great amount of dedication and

enthusiasm to music, and have no contact whatsoever with music that has

been written in the last hundred years. I feel this is a very

unhealthy situation.

BD: How can

we cure this?

DB: I don’t

know. I try in my own small way to keep

absolutely in touch with the music of today, and to perform it with a

certain regularity. Part of the problem is

that the new pieces are not played over and over again. How do

you expect somebody to go to a new work of Boulez or of Lutosławski or

whoever it may be, and hear it once and never hear it again

and like it. There’s the question of habit, of hearing this

music with a certain amount of regularity, which is very important.

BD: Will that

help to create a clamor for the

new works?

DB: I hope

so. That’s one of the

ways.

BD: In the

last few years, it seems that in some circles we’ve been coming back to

either tonality or a kind of tonality. Is this a good thing, or

just a thing?

DB: I’m not a

believer in neo. I don’t believe

in Neo-classicism and I don’t believe in Neo-romanticism. If it

is worth experimenting in order to find new

language, then it is positive and it’ll probably work. If it’s

just going back because we can’t find something else, then I don’t

think it will be substantial.

BD:

Specifically about new pieces, you

have a whole raft of them in your office that you’ve been asked to

play. How do you decide which

ones you will do?

DB:

[Matter-of-factly] I read them.

BD: Then what

is it you look for? What is it

that you want to find that will make you want to do this one or not do

that one?

DB: It

depends on the nature of the

piece. It is exactly like in the music of the past. There

are some works of the past that appeal to me because of the structure

or

because of the harmonic language, and others because of the color or

many other reasons. I don’t look for something specific, and if I

find it, that’s what I’ll do. The only thing that I look for is

something that is expressive and that is of interest.

BD: Do you

have any advice for someone who wants to

write a piece for the Chicago Symphony Orchestra, or indeed, any

orchestra these days?

DB: I cannot

give you a concrete piece of advice, no.

BD: Okay, but

you do encourage them to continue

writing?

DB:

Absolutely. Absolutely.

*

* *

* *

BD: What

advice do you have for

conductors coming along?

DB: To forget

recordings!

BD: Forget

them completely???

DB:

Recordings, yes. A young conductor came to

see me when I was still conductor-director of the Paris Orchestra, and

thought he should be engaged to conduct the orchestra. He

explained to

me why he thought he should do that. He was so good and he was

so talented, and he had a lot of enthusiasm, and he felt he could

really do wonderful things. So I said to him, “Suppose you were

given a concert. What kind of program

would you like to do? What kind of music appeals to you?” I

thought this way I would hear what really interested him, and he

said, “Anything that is in the Schwann

Catalog.” [Both laugh] That is a very sad state of

affairs. It’s a funny story, but it’s a very sad state of affairs.

The Schwann Catalog (previously Schwann Long Playing Record Catalog

or later Schwann Record And Tape

Guide) was a catalog of recordings started by William Schwann in

1949. The first edition was hand-typed, 26 pages long, and it listed

674 long-playing records. By the late 1970s, over 150,000 record albums

had been listed in Schwann.

The catalog initially focused on classical LPs, but also included

sections on popular music, jazz, musical shows, "Spoken and Misc.", and

so on. By the 1970s the catalog was split into two volumes: the monthly

Schwann-1 included all stereo classical and jazz recordings and stereo

popular albums less than two years old, while the semi-annual Schwann-2

included all monaural albums, older pop recordings, and spoken word and

miscellaneous albums. In May 1986, the publication became known as the Schwann Compact Disc Catalog.

Later, the catalog split into Schwann

Opus for classical music and Schwann

Spectrum for categories such as jazz, religious, spoken word and

international music.

The early editions indexed and reviewed LPs that contained the same

classical works. As the volume of music it catalogued grew, the amount

of information for each entry was reduced to a single line.

|

BD: You

should have challenged him to play Machaut, or something equally

incredulous!

DB:

Yes! When we recorded the Emperor

Waltz of Johann Strauss with the Chicago Symphony, I’d forgotten

my

score at home, and I took the score that was in the orchestra

library. There was a Forward

in the score that told a little

about Johann Strauss and about the waltz, etcetera, etcetera,

etcetera. It was a conductor’s score, and yet it told a little

about the composer and about the piece, and about Vienna in that

time. Then it said, “There is a very good recording of this piece

on

Such-and-such a label, conducted by so-and-so, for study

purposes.” [Both have a huge laugh] For study

purposes! If in a score you

are recommended to seek recordings for study purposes, then I think we

are not really

going to get very far!

BD: [Trying to

make sense of this] Are the musicians short-changing

themselves by not going to the score but rather going to the records?

DB: Well, the

recording cannot be a substitute for

studying.

BD: Should

the young conductors, perhaps, go to study

performances?

DB: Of course

they should study performances. They should have great curiosity

to see also

how things are achieved, to find out about the instruments, to find out

about the

orchestra, to find out about the structure of the music, and find out

about performances of other conductors.

BD: By

attending performances of other conductors?

BD: By

attending performances of other conductors?

DB: Yes, and

rehearsals, especially. It’s in rehearsals that you

can really learn much more.

BD: Despite

all this, you’ve made an immense number of recordings. Do

you conduct differently in the recording studio than you do when you’re

in concert hall or the opera house?

DB: No.

I conduct differently in different

acoustics. If I’m conducting in Orchestra Hall, then I

conduct differently than if I conduct in a very resonant church

because the sounds really only exist at that particular moment and in

that particular space. We are so used to living with the noise of

sound around us — noise of cars and of

elevators, and of hundreds of things that surround us — that

we have

sometimes difficulty remembering that sound in music really

exists only at that particular time and in a particular space.

It’s not just something that can be amplified. Those are

things that you can do for certain purposes which have nothing to do

with the music. It can be very laudable purposes, like education,

but it has nothing to do with the nature of the

music.

BD: So

there’s an artificiality to it?

DB: Yes, of

course.

BD: Perhaps

you should start each

Chicago Symphony concert with a minute or two of silence, to allow us

to listen to the hall before the sound comes in.

DB: The first

note that the orchestra plays, or

that any instrument plays, doesn’t exist on its own. It is

already in relation to the silence that precedes it. If the flute

would start the Prelude to

the Afternoon of a Faun, out of a lot of noise, or crackling

papers, or

whatever it may be, it’s a very different thing. The very first

note, the famous C-sharp, or the flute itself, is expressive in

relation to the silence that

precedes it. Therefore, silence is absolutely essential.

BD: Do you,

as the conductor, have any control over

that preceding silence?

DB: I don’t

have control over it. I wait in the

hope that it comes. I wait until it is really absolutely quiet,

and then I can

establish and feel that silence onto which will come the first note.

BD: So you

wait for your silence to come along?

DB: That’s

right.

BD: Do you

usually get it?

DB: Yes.

BD: Has your

relationship with the Chicago Symphony

changed at all now that you’re Music Director? You’ve been

conducting here for something like twenty years. These last

couple of years now, you’ve been Music Director. Is it different

at all?

DB: Not in

essence, no. The main difference is that as the Music Director

you don’t only

rehearse the works for a given concert, but you rehearse in such a way

that you build a common style to the orchestra and to you. In

other words, when you rehearse one Beethoven symphony, in a way you are

rehearsing also for the other symphonies, for the development of a

style of articulation, of balance, of color.

BD: Are you

rehearsing Beethoven, or are

you rehearsing Romantic Style?

DB: What is

Romantic Style? You rehearse everything that has to do with the

realization of music, articulation, and balance, every means of

expression that is expressed through sound. The work in question

gets brought to performance level as a

result of that work. But if you come as a guest conductor, then

you have three or four rehearsals, whatever the case may be. You

prepare the program and you give the best of yourself.

The orchestra gives the best of itself, and it’s finished.

BD: If you

are appearing as

a guest where you may or may not have conducted before, how

long does it take before the orchestra is yours?

DB: It would

be very difficult for me to answer this

question, because it’s so many years that I have not conducted in a new

situation. I don’t conduct out

of Chicago and Berlin, and once in a while

the Vienna Philharmonic. I conduct really only orchestras

with which I feel a great affinity.

*

* *

* *

BD: Is there

a secret to playing Mozart?

DB: Not more and

not less than to play something

else, except that it is more transparent, and therefore more

dangerous. You hear everything. Everything! The

slightest sin in phrasing or articulation, which can pass unnoticed, or

relatively noticed in other music, really strikes the eye

immediately. If the accent is too sharp or too soft, or the

balance is not right, or

the articulation is not exactly perfect, those things really jump

to the eye with Mozart.

DB: Not more and

not less than to play something

else, except that it is more transparent, and therefore more

dangerous. You hear everything. Everything! The

slightest sin in phrasing or articulation, which can pass unnoticed, or

relatively noticed in other music, really strikes the eye

immediately. If the accent is too sharp or too soft, or the

balance is not right, or

the articulation is not exactly perfect, those things really jump

to the eye with Mozart.

BD: [With a

gentle nudge] Is this to say you can get away with more in

Bruckner?

DB: In a

certain way, yes. In others, of course

not, but in a certain way, yes. It’s not as transparent.

BD:

Is there something special in the Mozart concerti when you are playing

and conducting? Is there a special affinity, or a deeper affinity

that you have

because you are both soloist and conductor?

DB: It’s not

a question of deeper affinity. It’s more a question of a greater

homogeneity, because if you

have a separate conductor, still you have to relate to him.

He is understanding what you are doing and then he transmits it to the

orchestra. Whereas this way, the channel is

directly from the soloist to the orchestra, and when the

orchestra does not have somebody in front of them beating every

quarter note, they listen also in a more sensitive way. So, it

brings out the best in everybody.

BD: When you

are conducting a guest soloist, are you, perhaps, a little more

sensitive to a

pianist than, say, a violinist or a bassoon player?

DB: I don’t

think so.

BD: You make

a conscious effort not to be?

DB: No.

I don’t even have to make a conscious effort because when I conduct

with a

piano soloist, I don’t think how I would play this piece. If he

is a convincing musician, then it is the same for me whether he

plays piano or violin.

BD: So you

wait to be convinced?

DB: Yes.

BD: Should

the audience wait to be convinced by you?

DB: I don’t

know.

BD: If money

were not a consideration, would you

bring more operas like the three by Mozart you did a couple of years

ago?

DB: I thought

the experiment of the Mozart

operas was very, very positive, and I would like to do some more,

yes. To have an orchestra of the quality of the Chicago

Symphony playing operas puts them really on a new level.

BD: Should

money, the expense, be a

consideration when you’re dealing with purely musical ideas of setting

up a season?

DB: Of course it

shouldn’t, but it is.

DB: Of course it

shouldn’t, but it is.

BD: How much

of a

burden is it for you to have these financial considerations?

DB: Difficult

question to answer. Some.

Of course it would be nice sometimes just to not think about financial

considerations and just do

this, that, and the other. But sometimes out of difficult

material situations there is even more spiritual

energy. Or sometimes out of difficult situations, one finds

solutions

that one wouldn’t find in a climate of total freedom from material

difficulties. For some time now, all

over the world we are fighting with the difficult economic situation,

and my hope is — as I’m sure everybody else’s is

— that it won’t last very

much longer. It would be very wonderful to be able to do the

Mozart

operas again, or to do another opera with the same setup.

BD: How much

should

you play the same works over again, and how much should you bring new

works and unknown old works to the audience?

DB: I think

you need a bit of both. You need to

be able to bring the works the audience knows and

loves, and bring them on as high a level as possible for the audience,

and also bring some new works in the hope that they will also become

known and loved.

BD: Is

conducting fun?

DB: Oh,

yes. Very much so.

BD: As Music

Director you have to plan at least

the season or two, or maybe even three or four in advance, at least

with some of your ideas. Do you like having these ideas so far

out in the future?

DB: Sometimes

yes, because it allows you to prepare

for special events or special series or a special idea, with

enough time to do it. Other times, of course, it is difficult,

because you don’t really know exactly what you will want to do two and

a half years from now on a Friday afternoon. It’s very difficult

sometimes, but altogether,

one gets used to that.

BD: You’re

never disappointed when you get to that

Friday afternoon two and a half years down the line?

DB: No.

BD: With all

of the various things you do — conducting, playing piano

solo and in chamber groups — how

do you divide your career among all of those things?

DB: I do four

months with the Chicago Symphony, I

do four or five months at the opera in Berlin, and I go to Bayreuth in

the summer. In between, whenever I can, I play the piano.

That’s all.

BD: Is there

something that you wish you

could give more time to, or do you just let it happen?

DB: Sometimes

there are periods when I

wish I could play a little more the piano than I do at the moment, but

in the situation that I am, trying to build the opera house in Berlin

again after so many years of difficult situation there, I can’t do

it. But with time, I hope I will be able to dedicate more time to

piano playing again.

BD: Is it

safe to assume that if you could, you’d

have 48 hours in every day rather than 24?

DB:

Absolutely. Wouldn’t you?

BD: Of

course! Thank you so much for chatting with me. I

look forward to the season.

DB: Thank you

very much.

© 1985 & 1993 Bruce

Duffie

These conversations were recorded at Orchestra Hall in Chicago

on November 2, 1985 and September 11, 1993. Portions were

broadcast on WNIB the following days,

and again in 1997. The first interview was published in Nit&Wit Magazine in March,

1986. This transcription of the second interview was made in

2015, and both were posted on this

website

at that time. My thanks to British soprano Una

Barry for her help in preparing this website

presentation.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been

transcribed and posted on this website, click here.

Award

- winning

broadcaster

Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975

until

its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His

interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since

1980,

and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM, as well

as

on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio.

You are invited to visit his website

for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of

other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also

like

to call your attention to the photos and information about his

grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a

century ago. You may also send him E-Mail

with comments, questions and suggestions.

Daniel Barenboim:

Ha! The joy is that one doesn’t have to

argue with stage-directors who go against the music! I mean this

in jest because I’ve had really wonderful experiences with

stage-directors. The Tristan

which I did in for three years

Bayreuth was with Jean-Pierre Ponnelle who is really the most musical

of stage-directors. But some of the Wagnerian opera acts lend

themselves rather well for concert performance. The second act of

Tristan, the third act of Siegfried, the first act of Walküre are

especially well-suited, although it is always incomplete because there

is no stage, and because they do form a very organic part of the whole

opera. But the main advantage of bringing the second act of

Tristan in concert here, of

course, is the Chicago Symphony. I

don’t think you will find an orchestra in the pit of this quality, and

for me this is almost enough reason. And the singers of Tristan

and Isolde are those who have done it with me for three years in

Bayreuth — really four years including the film

we made of it. So

it has really been worked out with a short time of rehearsal with two

people who have not sung it often onstage together, and with the same

conductor. So I hope that these performances will reflect some of

the joys and sweat that we have put into it.

Daniel Barenboim:

Ha! The joy is that one doesn’t have to

argue with stage-directors who go against the music! I mean this

in jest because I’ve had really wonderful experiences with

stage-directors. The Tristan

which I did in for three years

Bayreuth was with Jean-Pierre Ponnelle who is really the most musical

of stage-directors. But some of the Wagnerian opera acts lend

themselves rather well for concert performance. The second act of

Tristan, the third act of Siegfried, the first act of Walküre are

especially well-suited, although it is always incomplete because there

is no stage, and because they do form a very organic part of the whole

opera. But the main advantage of bringing the second act of

Tristan in concert here, of

course, is the Chicago Symphony. I

don’t think you will find an orchestra in the pit of this quality, and

for me this is almost enough reason. And the singers of Tristan

and Isolde are those who have done it with me for three years in

Bayreuth — really four years including the film

we made of it. So

it has really been worked out with a short time of rehearsal with two

people who have not sung it often onstage together, and with the same

conductor. So I hope that these performances will reflect some of

the joys and sweat that we have put into it. DB: No, I never

hear my own recordings. I have absolutely

no interest in them. Once they are made, for me they are a thing

of the past. The only time that I have sometimes listened to old

recordings is when I have replayed some of the Mozart concertos, and

some of the cadenzas were my own and I didn’t write them down.

But that is for a specific reason. I certainly would never dream

of sitting at home on a free evening and listen to my own recordings.

DB: No, I never

hear my own recordings. I have absolutely

no interest in them. Once they are made, for me they are a thing

of the past. The only time that I have sometimes listened to old

recordings is when I have replayed some of the Mozart concertos, and

some of the cadenzas were my own and I didn’t write them down.

But that is for a specific reason. I certainly would never dream

of sitting at home on a free evening and listen to my own recordings. DB: [Laughs] No,

this is not a six-hour question, it is an

impossible question. I don’t think there is a secret about

it. It is stylistically very difficult. It is so complete

that it doesn’t allow any underlining. This is what is so

difficult. In other words, when you play a phrase of Tchaikovsky

or Wagner or Brahms, or even of Beethoven, you can

underline certain elements or certain notes in the expression. In

Mozart there are always ten or fifteen or twenty different expressions

going on at the same time, and each one must have its own purity and

its

own independence. Mozart does not tolerate this kind of

underlining. The minute you start to make a point, you are

through with it.

DB: [Laughs] No,

this is not a six-hour question, it is an

impossible question. I don’t think there is a secret about

it. It is stylistically very difficult. It is so complete

that it doesn’t allow any underlining. This is what is so

difficult. In other words, when you play a phrase of Tchaikovsky

or Wagner or Brahms, or even of Beethoven, you can

underline certain elements or certain notes in the expression. In

Mozart there are always ten or fifteen or twenty different expressions

going on at the same time, and each one must have its own purity and

its

own independence. Mozart does not tolerate this kind of

underlining. The minute you start to make a point, you are

through with it. BD: Let me ask about

Beethoven. You’re going to be

presenting all thirty-two sonatas. Do they belong together as

a unit?

BD: Let me ask about

Beethoven. You’re going to be

presenting all thirty-two sonatas. Do they belong together as

a unit? BD: You’ve made a

recording of Il Martrimonio Segreto

by

Cimarosa. Why is that work not more well-known?

BD: You’ve made a

recording of Il Martrimonio Segreto

by

Cimarosa. Why is that work not more well-known?

DB: I don’t think

so. The main principles of putting together text and sound are

just as evident in the Verdi Requiem

as they are in opera.

DB: I don’t think

so. The main principles of putting together text and sound are

just as evident in the Verdi Requiem

as they are in opera.

BD: So it’s just the

performances that

should not be preserved but the music and the inspiration

should be?

BD: So it’s just the

performances that

should not be preserved but the music and the inspiration

should be? BD: Were they

thinking of late Tchaikovsky and

Dvořák and even Puccini as their moderns?

BD: Were they

thinking of late Tchaikovsky and

Dvořák and even Puccini as their moderns? BD: By

attending performances of other conductors?

BD: By

attending performances of other conductors? DB: Not more and

not less than to play something

else, except that it is more transparent, and therefore more

dangerous. You hear everything. Everything! The

slightest sin in phrasing or articulation, which can pass unnoticed, or

relatively noticed in other music, really strikes the eye

immediately. If the accent is too sharp or too soft, or the

balance is not right, or

the articulation is not exactly perfect, those things really jump

to the eye with Mozart.

DB: Not more and

not less than to play something

else, except that it is more transparent, and therefore more

dangerous. You hear everything. Everything! The

slightest sin in phrasing or articulation, which can pass unnoticed, or

relatively noticed in other music, really strikes the eye

immediately. If the accent is too sharp or too soft, or the

balance is not right, or

the articulation is not exactly perfect, those things really jump

to the eye with Mozart. DB: Of course it

shouldn’t, but it is.

DB: Of course it

shouldn’t, but it is.