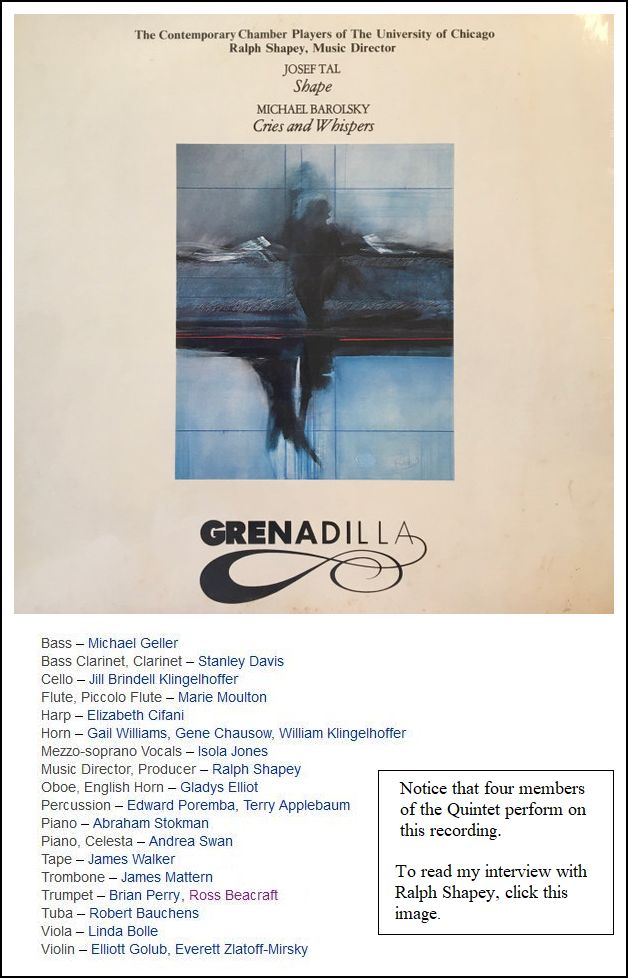

Trumpeter Ross Beacraft

A Conversation with Bruce Duffie

Ross Beacraft joined the faculty of DePaul

University in 1976 as a lecturer in applied trumpet and served in that capacity

and as chair of the brass department until 1996. He now oversees

all aspects of admissions, and chairs the financial aid committee for

the School of Music.

He continues to be a very active performer as Principal Trumpet

with the Chicago Brass Quintet, Chicago Opera Theater and the Elgin

Symphony Orchestra. In addition, he has performed often and recorded

with the Chicago Symphony Orchestra, Lyric Opera, the Chicago Chamber

Orchestra, Concertante di Chicago, Chicago’s ballet and theater orchestras,

and in many radio and television commercials.

Former appointments include principal trumpet with the Norwegian

Opera and Ballet Orchestra in Oslo, and third and assistant first trumpet

with the North Carolina Symphony.

|

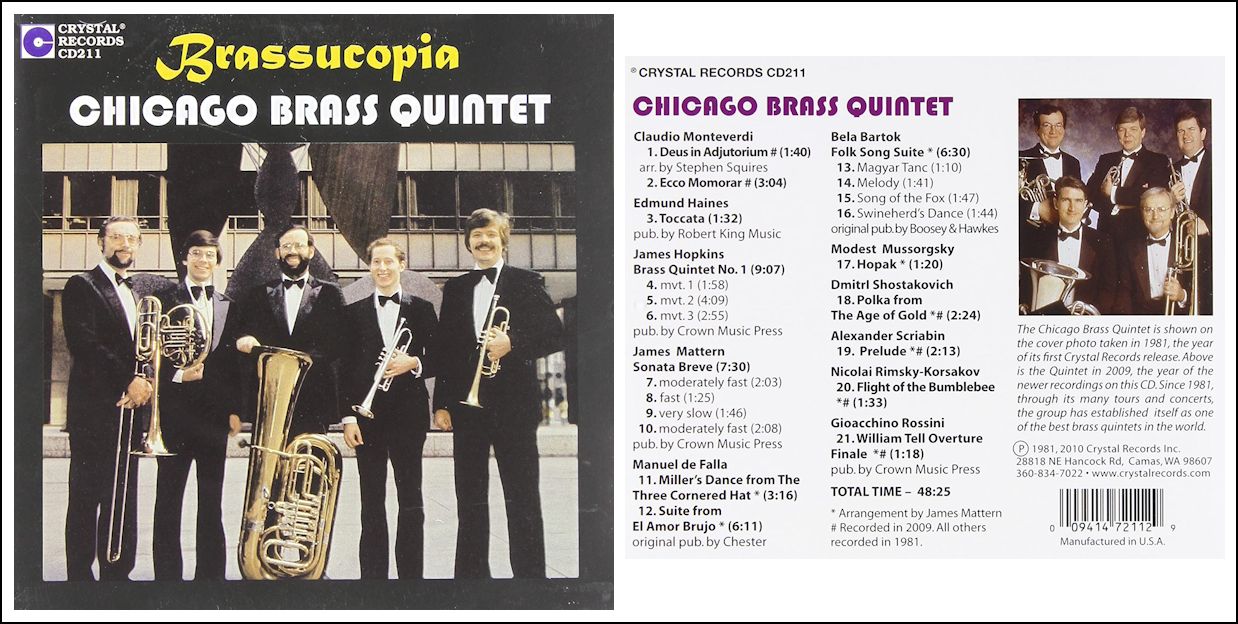

In April of 1997, the Chicago Brass Quintet was about to give

a special concert in their regular series, and to promote the event I had

a conversation with their First Trumpet, Ross Beacraft. As usual,

in addition to the specifics of that one performance, we chatted about other

musical ideas, and after presenting a portion of this interview on WNIB,

Classical 97, I am now pleased to be able to place the entire encounter on

this webpage . . . . .

Bruce Duffie: Who were the founding members

of the Chicago Brass Quintet?

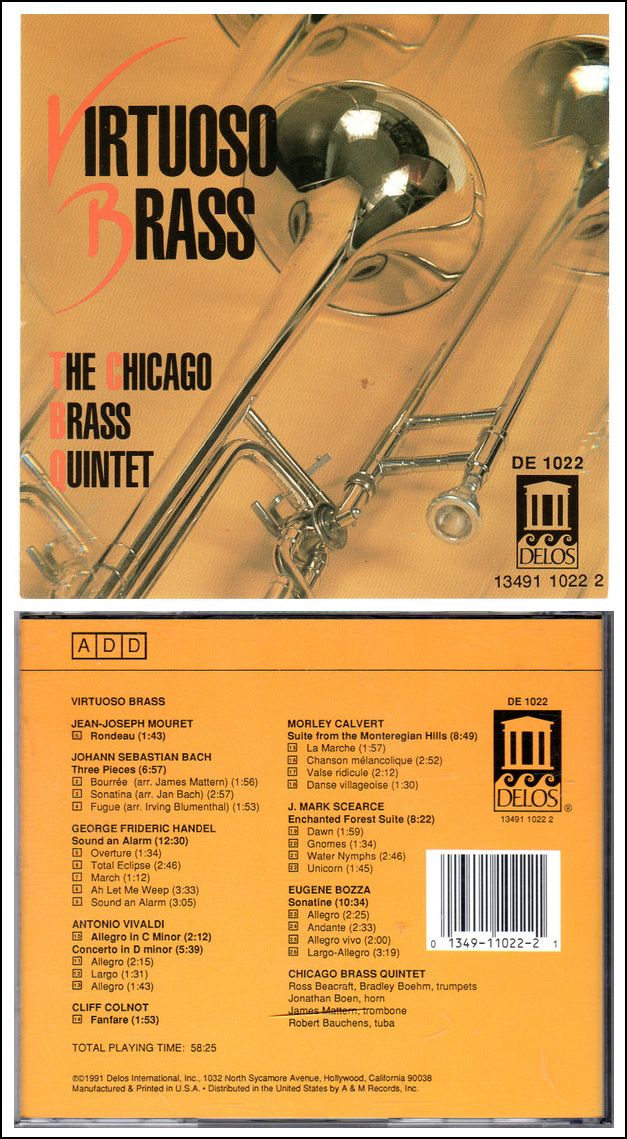

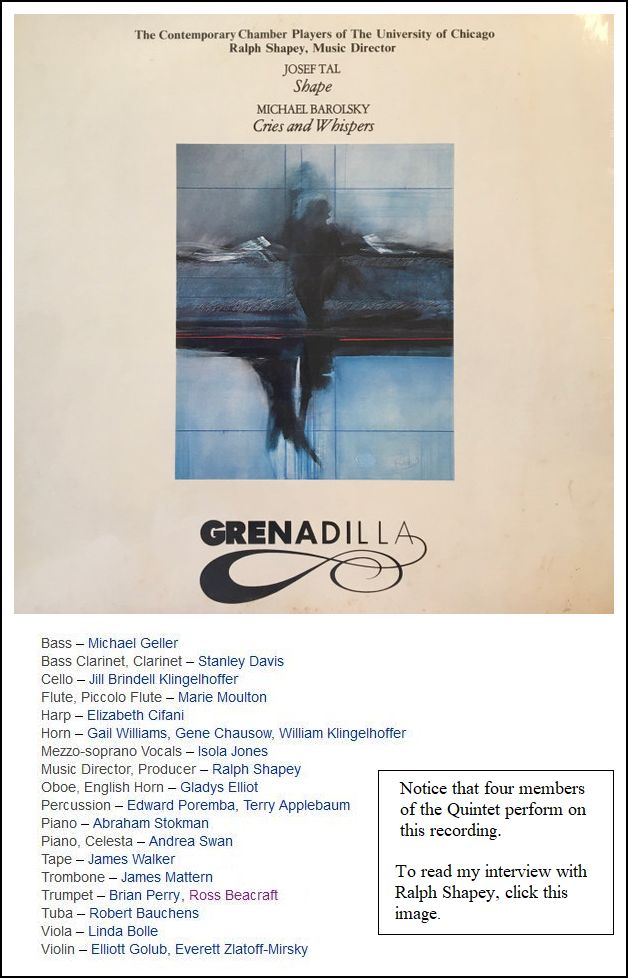

Ross Beacraft: James Mattern [trombone] is the

only current member in the Quintet who was a founding member. The

group was formed in 1963, and the rest of the original people were Paul

Tervelt, who was Principal horn in the Milwaukee Symphony for a number

of years; Charles Geyer, who was the Fourth and Second trumpet of the Chicago

Symphony for a number of years, who went to Houston and played Principal

there, and has been teaching at Eastman in the last few years; Brian Perry,

who is Principal trumpet with the Lyric Opera; and Robert Bauchens, who’s

the tuba at Lyric. Over the years the commitments took them in various

different directions, and some other people came in.

BD: When did you join?

Beacraft: I joined the Quintet when Charlie

left to play in Houston, which was in 1976. I had just come back

from playing in Norway. I subbed with the Quintet for a while, and

they decided to make it official, and asked me to join permanently.

BD: So, you’ve been there more than twenty years.

Beacraft: I guess I have... wow! [Laughs]

It does add up, doesn’t it?

BD: Do you also play orchestra gigs?

Beacraft: Oh yes. I do a lot of different

kinds of things in Chicago. I came for the interview this evening

right from an Elgin Symphony concert, where we played the Franck Symphony

in d minor.

BD: Is there a lot of difference playing trumpet

in an orchestra, as opposed to being one of five in a quintet?

Beacraft: You use the same kind of sensibilities.

You listen to your colleagues, and you have to have a keen sense of time,

pitch, phrasing, and style. All those things are similar, whether

it’s a solo piece, or a chamber music, or an orchestral piece. The

dynamic levels in the symphony orchestra are probably wider on the fortissimo

end than anything we would reach with just the five of us in a quintet.

Although we can play fairly strongly, we wouldn’t reach the super triple

fortes you would with a hundred-piece symphony orchestra.

In the Quintet, you typically have some control of what you do and when you

do it, more than you can with an orchestra where you are one of a bunch of

people, and you have to go with what the conductor says, and the architecture

of the piece that the conductor is putting forth. In the Quintet, you

only have five, so you have a lot more give-and-take to argue or fashion

with the other four members how eventually we come across.

BD: Is it like a five-sided marriage?

Beacraft: Sometimes it feels like that yes, very

much so! Each person has his say, and some people you know what they’re

going to say. If you play with them for a long time, you sense what

that person will do.

BD: Is that a good surprise or a bad surprise?

Beacraft: Oh, it not a surprise at all.

Actually, it’s a good thing. Good chamber music doesn’t happen

in a year. It happens over many years together of sharing your

ideas. Then, each new person to the group establishes his or her

personality on that group after some period of time.

BD: How long has this current group been together?

Beacraft: The newest member of our group is Matthew

Lee, who joined us just a year and a half ago. He’s the other trumpet

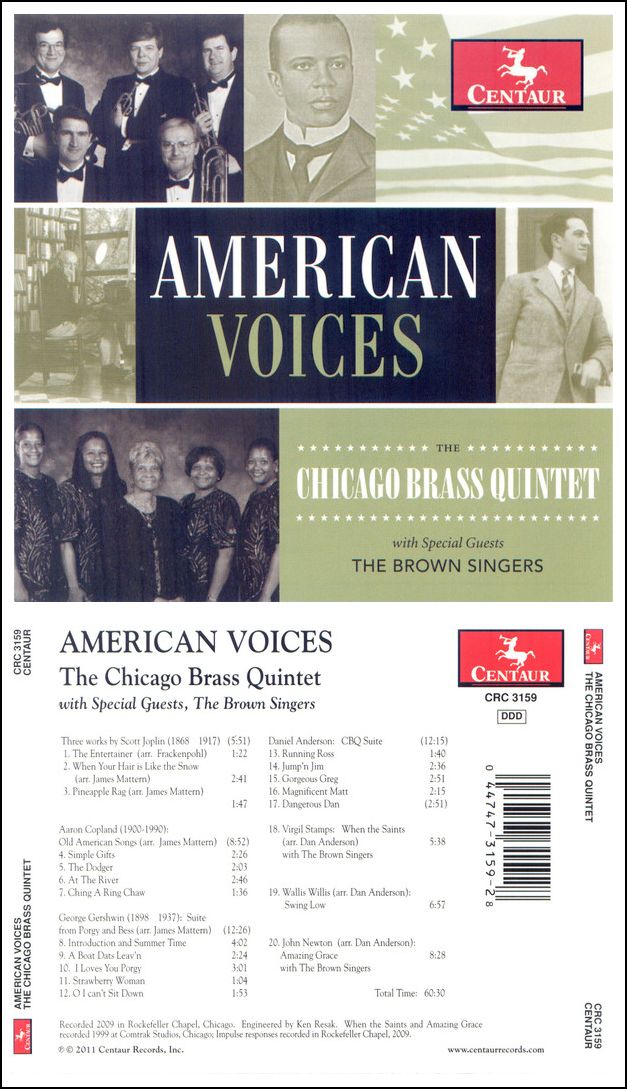

player. The tuba player, Dan Anderson, and the French horn player,

Greg Flint have been with us for about five years. Jim’s the grandfather

of all of us, and he’s been there since the beginning.

BD: Does that give him any more say so about

what goes on?

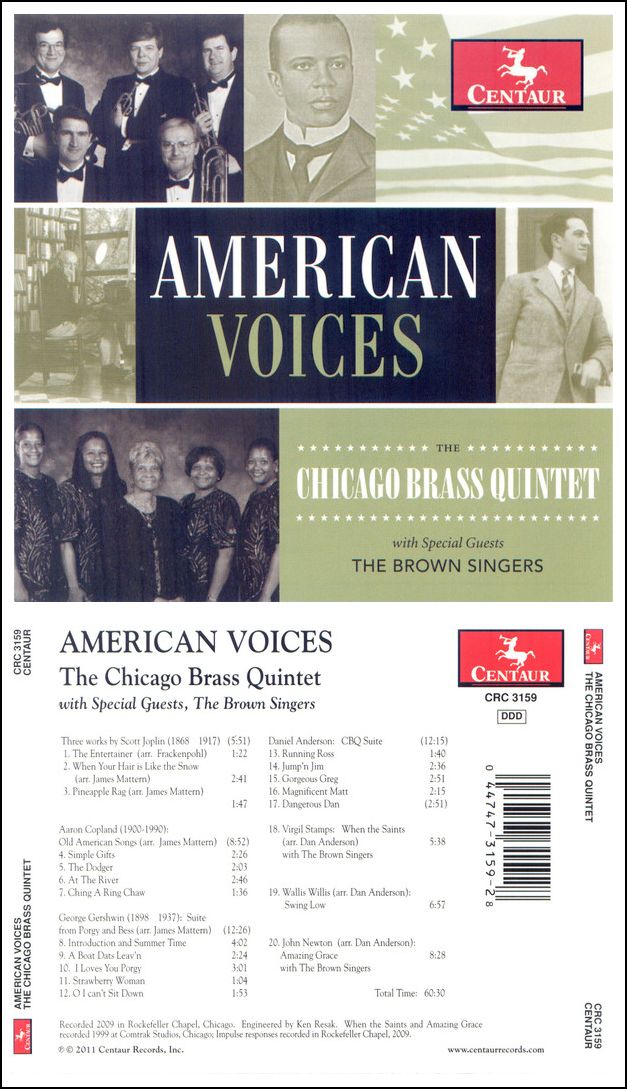

Beacraft: He brings a unique contribution to the

Quintet in that he has done many of the arrangements over the years, and

a number of original compositions which we have premiered and been major

exponents of. In that way alone he’s put a very major stamp on the

Chicago Brass Quintet. Since joining, Dan Anderson has brought another

ability to the Quintet. Dan is a marvelous jazz string bass player,

as well as being a great tuba player for both classical and jazz. He’s

done a number of arrangements for us in that vein, which is something we’d

never done before. He has also coached us and helped us play in

those styles, so it’s expanded our horizons. It’s

fun to play Bach, and Handel, and Vivaldi on the same concert that we’ll

be playing things by Dizzy Gillespie and Stanley Turrentine.

BD: Is it true that music is music is music,

no matter what it is?

Beacraft: It depends on each personality, but

the members of our Quintet enjoy making all kinds of music. I’m

a music junkie. I literally like all kinds of music. I can

easily listen to [Strauss’s] Elektra, and an hour later be listening

to Country & Western. You listen on different levels, and for

different kinds of enjoyment.

BD: Do you listen differently because you generally

are a music-maker rather than just a music-consumer?

Beacraft: It’s a hard question for me to answer

because I’ve been a music-maker since I was eight years old. So,

I don’t know what it’s like to just be a consumer. Honestly, I couldn’t

answer that.

BD: Are you conscious of the consumer —

the audience — that

is there each night when you’re playing?

Beacraft: Yes, I think so. I’ve done a fair

amount of studio playing in my life, and it’s a whole different feel

when you’re playing just for a microphone than when you’re playing for

human beings. For me, the real thrill is playing for people, and

you can sense very much when you have an audience that becomes on the same

wavelength that you are on, and they join you. Then that concert

becomes a very special evening when you begin to feed off their energy,

and they feed off yours, and the whole thing rises to a different level.

So yes, it’s impossible not to be aware of the audience as a performer.

BD: Is there a different kind of awareness when

you’re playing chamber music as opposed to an orchestral performance?

Beacraft: Yes. As an orchestral player,

you get wound up in this incredibly great music. Many of the great

composers of past centuries have done some of their greatest works for

large symphonic forces, and when you get rolling around with that sound

you become part of it, and it just takes off from you. You don’t

get quite the personal connection to the audience and their involvement

with the music. As a performer of only five, you have a connection

with your audience, which you don’t get when you’re one of one hundred.

You don’t get the overwhelming sound pillow in the Quintet that

you do in a symphony orchestra. When you’ve done something somewhat

very special, and it’s only you doing it, you can get a real connection

with an audience. So, each one has its unique thrill.

BD: A number of conductors have said they like

to try and make their orchestra play as if it’s

chamber music. You’re a chamber musician and an orchestral musician.

Is it really possible to play chamber music in an orchestra?

Beacraft: All great orchestral musicians play it

that way. It’s impossible not to. Music is an aural skill

more than a visual one, so although you watch a conductor, you listen,

and listen, and listen, and listen while you play.

BD: Then let me ask a really easy question.

What’s the purpose of music?

Beacraft: [Bursts out laughing] I don’t

even think there is an answer to that! I know what I get out of

music, and that’s enough for me. It’s probably something very unique

to each person, and maybe that’s how it should be.

* * *

* *

BD: Chicago is known for its brass players.

Is it special to be an established brass player in Chicago?

Beacraft: That’s what drew me here. When

I got out of school I got a job right away with the North Carolina Symphony.

It was a good job, and it was great to have a job right out of school.

Many musicians don’t get that luxury, but there was something missing

in my own playing and in the playing I heard around me that I needed to

have. I got on a bus to Chicago with nothing in my pocket.

The first day I was here I found my way to Orchestra Hall, and they were

doing Also sprach Zarathustra at 1 o’clock on a Friday afternoon.

I went up and sat in the gallery, and I cried my eyes out. I couldn’t

believe it could sound like that. I’d heard the record many times,

and this was so much better. I knew at that point I had to move here

and learn to play like that. There are great brass musicians in this

town, not only the fine members of the Chicago Symphony, which is world-renowned,

but there’s probably a greater depth of brass playing of anywhere that

I’ve ever known.

BD: I would think that it would be almost

infectious — that in order to

stay here, you really have to be on that level.

Beacraft: Yes. There are so many fine

players, and it’s a great place to be a freelance trumpet player.

BD: Is there perhaps too much competition?

Beacraft: No. That’s a subjective thing.

What’s too much, or what’s enough for me?

BD: Is there enough work for everybody?

Beacraft: My experience has been that those people

who are really fine musicians, and are willing to work very hard, and

have a great deal of endurance, they eventually find their own niche, and

they have a number of really fine things to play. If you’re a young

person coming into Chicago, very rarely does someone get all the premier

jobs the first day or two. You have to pay a few dues along the way.

But if you show-up, and you play well each time, and you have the sensitivity

to play with those around you, and to not try and take over with your own

personality, you will ultimately be very successful here.

BD: Do you always play the standard trumpet,

or do you also use a baroque trumpet, or a little trumpet, or a big trumpet?

Beacraft: I play all the trumpets. I have

occasionally played the baroque trumpet, although I would not consider

myself a specialist at that. I have to work very hard to play the

natural trumpet, and I need some time to do it well. But the other

instruments I play with great frequency. I practice every day on

a B-flat trumpet, on a C trumpet, on a piccolo trumpet, and on an E-flat

trumpet, too. I also enjoy playing the cornet very much, and I play

that with a great deal of frequency. I have rotary valve instruments

which I like for certain literature. I probably own about fourteen

or fifteen different trumpets.

BD: So, you can put the right instrument on

each piece?

Beacraft: Yes. In an orchestral situation,

I like to play the music of Brahms and Mozart on rotary valve instruments,

and certainly Wagner and Bruckner fit very well, and also Mahler.

I don’t get a chance to play much Mahler unless I’m an extra with the Chicago

Symphony. In Elgin we’re doing the Mahler First next year,

and we’ve done the Second and Fourth, but I like to play

those things a great deal.

BD: Coming back to the Chicago Brass Quintet, there

are concerts here in Chicago. Do you also tour?

Beacraft: Yes. In fact, tomorrow we hop

over to the University of Tennessee in Johnson City. We will take

a charter out of Midway, and be back home by about 1.30 in the morning.

The next day, we’ll be rehearsing at Holy Name Cathedral for the upcoming

concert there.

BD: Do you do a lot of touring?

Beacraft: A fair amount. If you took all

of our tour dates and put them end to end in any year, we would probably

do between a month-and-a-half to two months of touring dates.

BD: Are they all a day or two here, and a day

or two there?

Beacraft: Usually. We have one extended residency

we’ve done for eight years now at the Lancaster Festival in Lancaster,

Ohio. We serve as artists-in-residence and principal players in the

orchestra. We do lots of chamber music, and things like that.

This summer, at the end of August, we’ll go to Taiwan for a week, and do

five concerts there. We also usually go to Florida every other year.

We’ll do a week during the winter, and it’s a nice time to get away from

the sub-zero temperatures of Chicago. [Both laugh] We tour a

lot throughout the Midwest, and pretty much all over, and quite frequently

it’s Friday, Saturday, Sunday, and then we’re back home. The date

we’re doing tomorrow is just the one-night

— out and back in the same day.

BD: You’re not even staying in a hotel?

Beacraft: If it works, it’s nice because we

would just as soon sleep in our own beds. Of course, most of us

are very busy in Chicago. We have things that we could be doing here,

rather than just being on the road.

BD: You wouldn’t rather be a group that does

nothing but tour all over, and be a traveling roadshow?

Beacraft: Absolutely not! I respect people

who do that, but it’s a very hard life. When you first begin it,

you think that touring is very glamorous, but you find out very quickly

that airplanes and rent-a-cars and even very nice hotel rooms are not

all that terribly glamorous. You do it for the music and the experience

of playing, and that never loses its joy, but I have a family, as most

people in the Quintet do. I like spending time with them, so I really

like the level that we’re involved with. We have fifty or sixty concerts

a year with the Quintet, and that way we still have home-lives. I

wouldn’t want to give up the symphonic playing, or the opera playing.

I enjoy those things, and it’s a great mix. In many ways I’m very,

very lucky, and very fortunate.

BD: You’re Principal with the Lyric Opera orchestra?

Beacraft: No, I’m Principal with the Chicago

Opera Theater. Brian Perry is the very, very fine Principal of Lyric

Opera.

BD: But you also play with Lyric?

Beacraft: I do. For many, many years I’ve

been very fortunate. They’ve been kind enough to call me to do

a lot of the on-stage and off-stage work there. I’ve really had

great joy to do that for almost twenty years now.

BD: Are you one of the herald trumpets in Aïda?

Beacraft: Yes, and I’ve been one of the trumpets

in Lohengrin, and Die Meistersinger, and La Bohème,

and Turandot, and this year Don Carlo. Yes, there’s

great literature to do.

BD: It’s great that a brass player actually

knows about these things.

Beacraft: I love opera. One of my early

professional jobs was as Principal Trumpet with the Norwegian Opera and

Ballet in Oslo. That was really a nice introduction. I was

twenty-six or twenty-seven, and being able to learn that literature was

great.

* * *

* *

BD: Do you play the same for the microphone

as you do in concert?

Beacraft: You try. Most of our recordings

have been done in a concert hall situation, or in a church. Early

on we tried to do a studio recording, and we didn’t like it at all.

BD: Why?

Beacraft: The acoustic was unnatural, and when

they added reverberation, to me it still felt cramped. I like very

much more to do location-recordings in a recital hall, or in a church,

or in an acoustic where what you get on the record is actually the sound

we produced. It’s not something that’s been manipulated.

BD: If you get the sound right in the hall,

a good engineer will catch it, rather than try to recreate it someplace

else?

Beacraft: Exactly, and it’s much easier to play

because you feed off what you’re hearing. In a recording studio,

the acoustic is very dead. The engineers can control the resonance,

but you don’t hear that when you’re playing, and that’s always unnatural

for me.

BD: [With a gentle nudge] It bums you

out?

Beacraft: [Smiles] Yes, it really does.

But that’s for classical chamber music. It’s

a whole different story to get it all in one when you do a jingle.

That’s where the studio situation belongs. It works very well for

that.

BD: Do you like playing jingles?

Beacraft: It’s a different challenge.

You never see the music before you get there, so you have to be a very

good sight-reader. You have to be very accurate, and play it very

well in tune and in time, so you’re in and out in an hour. You’re

usually with some of the better musicians, and it’s quite different. You

don’t get the extended pieces. Thirty seconds or sixty seconds of

playing doesn’t give you same joy you get with a piece which lasts thirty

minutes, and that you’ve worked on for months. It’s just a different

discipline.

BD: Does it irk you or please you when you hear

a commercial and you’re in it?

Beacraft: If I sound good on it, it pleases

me. [Both laugh] Usually, even the great parts they put far

in the background because of the voice-over, so you can hardly hear it.

You forget you’ve even done them half the time. [More laughter]

BD: Tell me the details of this concert coming

up.

Beacraft: This concert is going to be something

that we’ve talked about doing at Holy Name for a long time, and they finally

asked me to see if I could put it together this year. The idea

was to invite the Chicago Symphony Brass Ensemble to join with the Chicago

Brass Quintet in doing a brass spectacular, and investigate the possibilities

of all the antiphonal things we can do at the cathedral. They have

a really terrific Casavant organ downstairs, and another spectacular organ

upstairs, so that gives us the possibility of doing things like the Grand

Cor and Dialogue by Eugène Gigout. We’re also going to

do the Canzon in echo duodecimi toni by Gabrieli, where we’ll use

that antiphonal space.

BD: Do you have to be careful of the reverberations

in that huge space?

Beacraft: That’s the trick, and to try and play

it in time, and keep it together. We’ll be rehearsing early there

Tuesday morning to try and do just that, and probably have other rehearsals

throughout the week just to deal with those kinds of things. We’re

going to open the concert with the Vienna Philharmonic Fanfare

of Strauss [1924], and we have a unique thing that’s going to happen.

Sal Soria, the brilliant organist at Holy Name, and who has won an award

for his improvising, will pick up where we leave off, and begin improvising

with the Straussian harmonies, and take us from there to the Gabrieli

harmonies in his improvisation. When he’s finished, we will play

the Duedecimi Toni. It will create a great atmosphere, and

I look forward to that. We’ll also do a Baroque suite, which will

feature the music of Dietrich Buxtehude, Gottfried Reiche, and Jeremiah

Clarke. Then the Chicago Symphony Brass Ensemble will play Praise

to the Lord with Cymbals and Drums by Siegfried Karg-Elert, and St.

Michael, the Archangel from Church Windows by Ottorino Respighi,

which was arranged by Mark Ridenour, who is the associate first trumpet

with the Symphony, and who plays with the ensemble. Then we’ll end

that half with the Poème Heroïque by Marcel Dupré.

So that’s almost enough for a concert by itself, just in the first half!

[Both laugh] Actually, some of the pieces are short, so it

should be about forty-five minutes for the first half. Then after

the intermission we’ll come back and do some music of James Mattern. One

piece, his Fanfare and Flourish, was actually commissioned by the

First National Bank about ten years ago. They did a series of brass

concerts during the summer, and they wanted a piece which could be played

either with a small group or a large group, and he wrote it so it could

be done either way. We’ve adapted it to use the organs in the Cathedral.

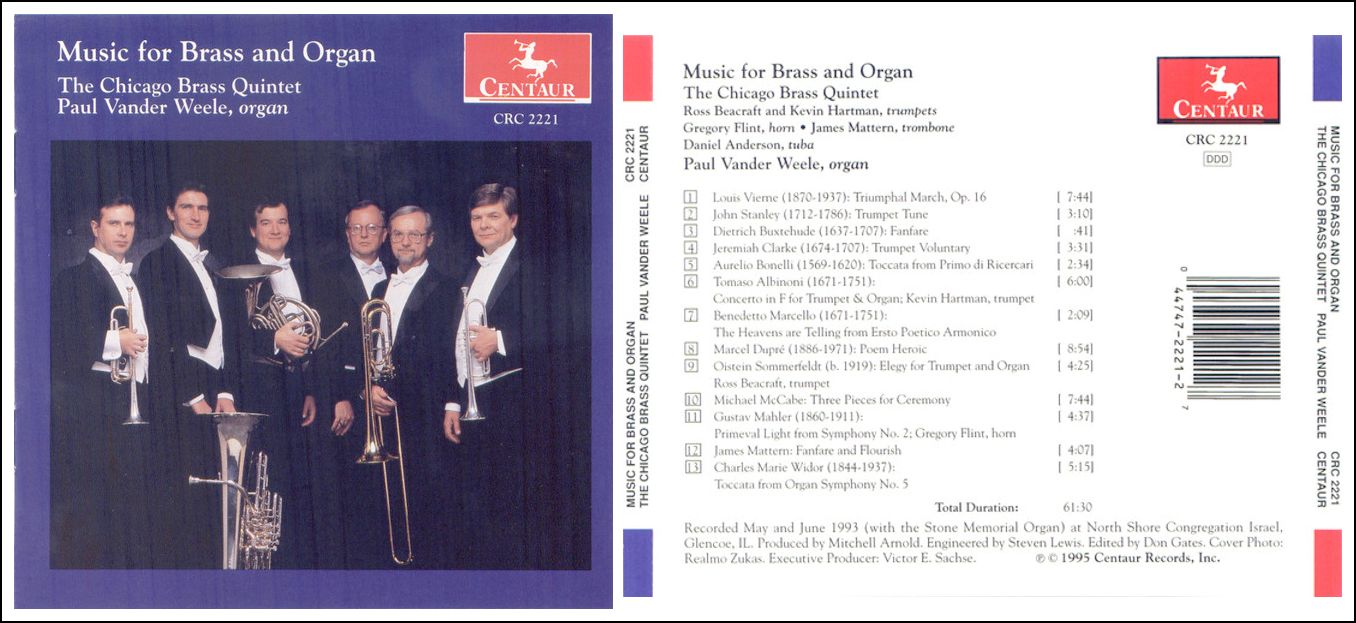

It’s on our album of organ and brass music, which is on Centaur [shown

below]. Then the low brass guys, Jay Friedman and Charlie Vernon from the

Chicago Symphony, and James Mattern will combine with with our tubist,

Dan Anderson, to do Crucifixus by Antonio Lotti, and Four Little

Prayers of St. Francis of Assisi by Francis Poulenc. The trumpets

will have their day with The Fanfare for St. Edmundsbury by Benjamin

Britten. Then after we do the Grand Cor and Dialogue by Eugène

Gigout, we’ll

lower our hair a little bit, if you like, by doing a traditional spiritual

called Swing Low, Sweet Chariot, which Dan Anderson arranged, and

which goes through various different styles of music. He’s also written

a piece especially to end this concert for both organs, and

both brass ensembles. If you can imagine raising the roof at Holy

Name Cathedral, this might do it.

BD: It sounds like a great concert.

Beacraft: It’ll be fun, and it’ll probably have

its loud moments and soft ones.

BD: Do you have you any advice for other brass players?

Beacraft: Practice, practice, practice, and listen,

listen, listen! Actually, I would hesitate to give advice to anyone.

BD: Do you do any teaching?

Beacraft: I taught for twenty years at DePaul

University. I was the trumpet instructor there, and I really enjoyed

it very, very much. It’s always a joy to work with someone, and help

them realize their potential. Each person brings something different

when they come to you, and if you’re a good teacher, you work with them

to try and bring them up to their best level, and to find out where their

deficiencies are to help them expand their horizons. So my advice

would be that each person should realize their own potential in their own

way. But then my life took a left-turn, and I became Director

of Admissions for the School of Music.

BD: Does this mean you have to listen to all

the audition tapes?

Beacraft: No. All the students come in

to audition, but there are certain rewards with youngsters who are just

about to go to college. They come with enthusiasm, and it’s a good

place for them to be.

BD: One last question. Is playing

the trumpet fun?

Beacraft: There’s nothing more fun. If

I have a day off, my favorite thing to do is practice the whole day.

That’s what I like to do. [Pauses a moment] There are other

things, too... That’s not to say it is the only thing in life.

After all, it’s people who are the most important, and my family comes long

before the trumpet does. But I do get a kick out of it, and most musicians

I know play because they get such joy from playing. Economic rewards

are secondary.

BD: I hope it continues.

Beacraft: Thanks.

© 1997 Bruce Duffie

This conversation was recorded in Chicago on April 6, 1997.

Portions were broadcast on WNIB two days later. This transcription

was made in 2022, and posted on

this website at that time. My

thanks to British soprano Una Barry for her

help in preparing this website presentation.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed

and posted on this

website, click

here. To read my thoughts on editing these interviews

for print, as well as a few other interesting observations, click here.

* * * *

*

Award -

winning broadcaster

Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical

97 in Chicago from 1975 until

its final moment as a classical station in

February of 2001. His interviews have also

appeared in various magazines and journals since

1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM, as

well as on Contemporary

Classical Internet Radio.

You are invited

to visit his website

for more information about his work, including

selected transcripts of other interviews,

plus a full

list of his guests. He would also like to call

your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather,

who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago.

You may also send him E-Mail with comments,

questions and suggestions.