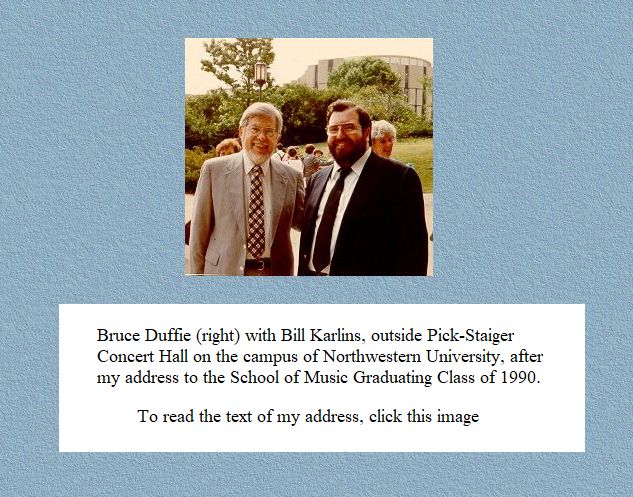

The key to my sorting system was to celebrate

round birthdays, and early in 1992, when Karlins was about to turn

sixty, we arranged to meet and chat about things musical.

The key to my sorting system was to celebrate

round birthdays, and early in 1992, when Karlins was about to turn

sixty, we arranged to meet and chat about things musical. BD: Do students today want to become big

rock stars?

BD: Do students today want to become big

rock stars?|

Bebop or bop is a style of jazz developed in the early to mid-1940s in the United States, which features compositions characterized by a fast tempo, complex chord progressions with rapid chord changes and numerous changes of key, instrumental virtuosity, and improvisation based on a combination of harmonic structure, the use of scales and occasional references to the melody. Bebop developed as the younger generation of jazz musicians expanded

the creative possibilities of jazz beyond the popular, dance-oriented

swing style with a new "musician's music" that was not as danceable

and demanded close listening. As bebop was not intended for dancing,

it enabled the musicians to play at faster tempos. Bebop musicians

explored advanced harmonies, complex syncopation, altered chords, extended

chords, chord substitutions, asymmetrical phrasing, and intricate melodies.

Bebop groups used rhythm sections in a way that expanded their role.

Whereas the key ensemble of the swing era was the big band of up to fourteen

pieces playing in an ensemble-based style, the classic bebop group was

a small combo that consisted of saxophone (alto or tenor), trumpet, piano,

guitar, double bass, and drums playing music in which the ensemble played

a supportive role for soloists. Rather than play heavily arranged music,

bebop musicians typically played the melody of a composition (called

the "head") with the accompaniment of the rhythm section, followed

by a section in which each of the performers improvised a solo, then

returned to the melody at the end of the composition. |

BD: This was more music to listen

to, rather than music to dance to, even though they were still dance

bands?

BD: This was more music to listen

to, rather than music to dance to, even though they were still dance

bands? Karlins: You asked a good question

earlier about whether I compose for the audience, or for an audience,

and my truthful answer was that I do. But I must assume that

the audience thinks pretty much exactly the way I do, which they don’t.

But how can you express anything otherwise? It depends on

the genre. Are you writing chamber music? Are you writing

a ballet? Are you writing a piece for an orchestra, or an opera?

All these have different kinds of audiences, and we know that

some are more conservative than others. But if you’re writing

for a large audience, how can you do other than just trust yourself,

and trust your own emotions? What you probably can do is know

that if you simplify, and simplify, and simplify, you’ll reach more and

more people.

Karlins: You asked a good question

earlier about whether I compose for the audience, or for an audience,

and my truthful answer was that I do. But I must assume that

the audience thinks pretty much exactly the way I do, which they don’t.

But how can you express anything otherwise? It depends on

the genre. Are you writing chamber music? Are you writing

a ballet? Are you writing a piece for an orchestra, or an opera?

All these have different kinds of audiences, and we know that

some are more conservative than others. But if you’re writing

for a large audience, how can you do other than just trust yourself,

and trust your own emotions? What you probably can do is know

that if you simplify, and simplify, and simplify, you’ll reach more and

more people. BD: I assume that you think that all these ideas

— the radical, the conservative, and

everything in between — should coexist?

BD: I assume that you think that all these ideas

— the radical, the conservative, and

everything in between — should coexist? BD: Either musically or in your teaching

career, are you at all where you thought you would be years ago when

you hit sixty?

BD: Either musically or in your teaching

career, are you at all where you thought you would be years ago when

you hit sixty? BD: You might have the right musicians

playing in a dead hall, for a sleepy audience, at the wrong time

of day, next to a noisy street.

BD: You might have the right musicians

playing in a dead hall, for a sleepy audience, at the wrong time

of day, next to a noisy street. BD: So then you view music as a visual,

and also a collaborative art?

BD: So then you view music as a visual,

and also a collaborative art?© 1992 Bruce Duffie

This conversation was recorded in Chicago on January 6, 1992. Portions were broadcast on WNIB the following month, and subsequently there, and on WNUR in 2002, 2005, and 2018, and on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio in 2005. This transcription was made in 2020, and posted on this website at that time. My thanks to British soprano Una Barry for her help in preparing this website presentation.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website, click here.

Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM, as well as on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio.

You are invited to visit his website for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.