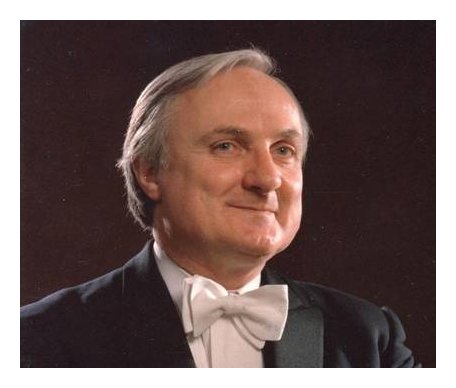

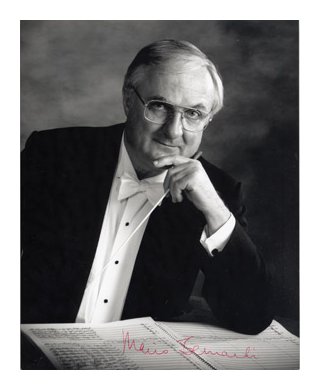

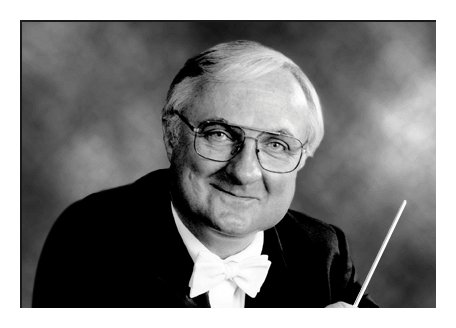

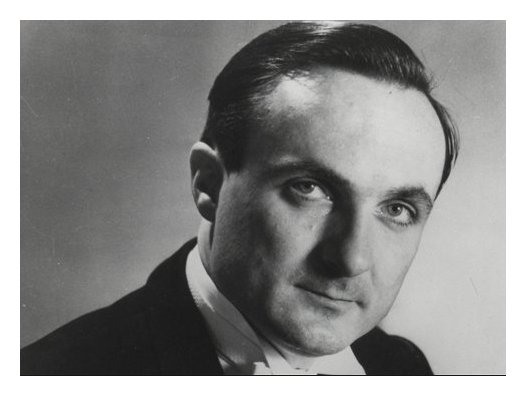

Mario Bernardi, NAC Orchestra’s founding conductor,

dies at 82

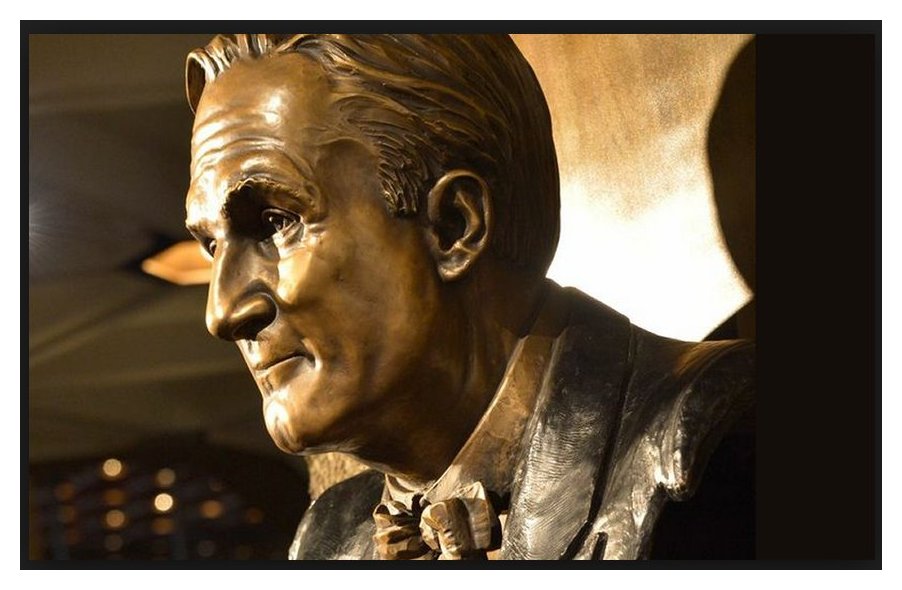

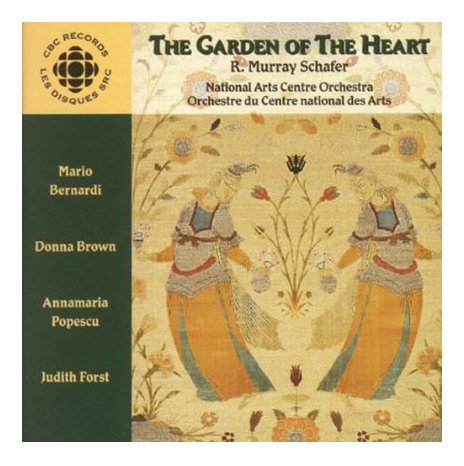

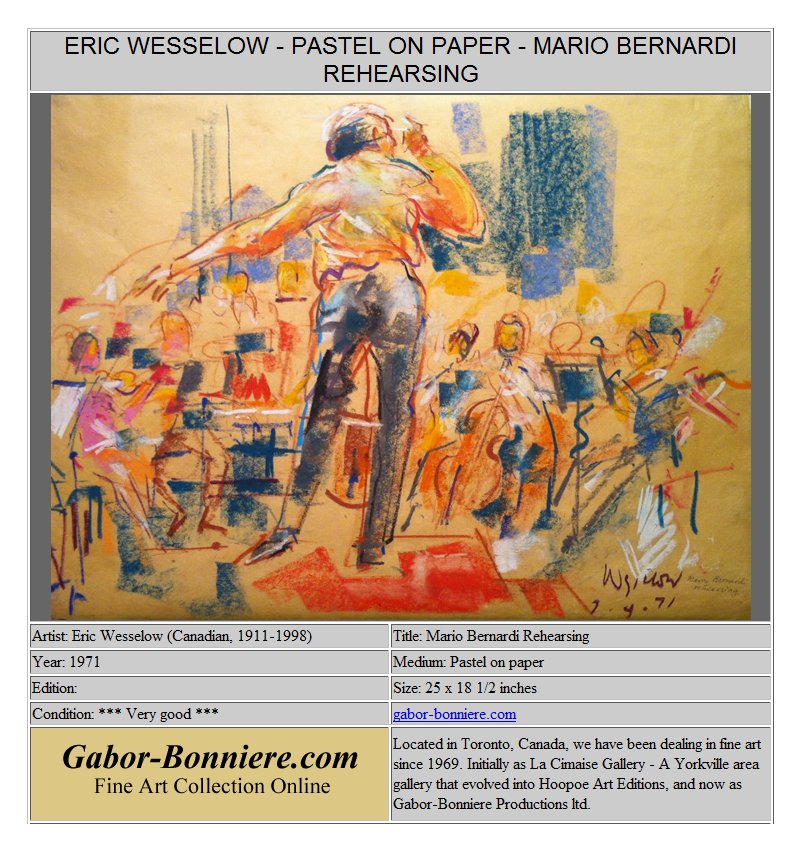

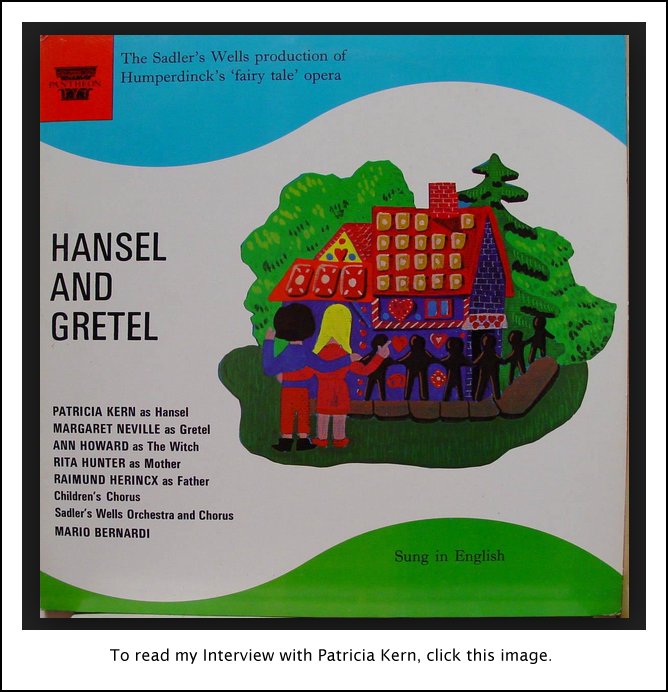

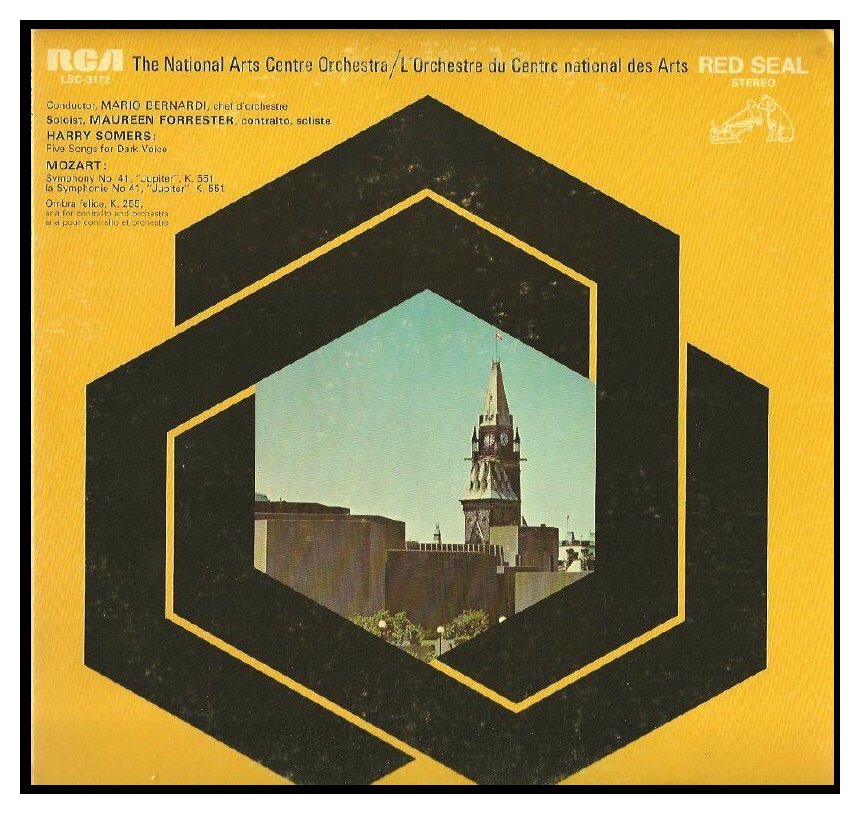

Published Monday, Jun. 03, 2013 12:15PM EDT [Text only] Mario Bernardi, the founding conductor of the National Arts Centre Orchestra in Ottawa, has died. He was 82. The NAC says it’s lowered its flag to half-mast in tribute to the revered conductor and pianist, who died Sunday in Toronto. “Mario Bernardi was a national figure who played a seminal role in the life of classical music in Canada,” Peter Herrndorf, president and CEO of the NAC, said in a statement. The Kirkland Lake, Ont., native moved to Italy at age 6 with his mother and studied at the Venice Conservatory. He started his career with the Royal Conservatory Opera School in Toronto and conducted at the Canadian Opera Company in his mid-20s. In 1963, he moved to London and served as musical director of the Sadler’s Wells Opera Company (now the English National Opera). Five years later he joined the NAC and recruited young musicians to build the 45-member orchestra. “He shaped them into a wonderful orchestra, drawing from them a unique sound which was praised by music critics for its transparency and precision of ensemble,” said Herrndorf. Bernardi also led the orchestra on tours of Canada and Europe, and created the summer opera festival at the NAC. After he left the centre, he led the Calgary Philharmonic Orchestra and was the principal conductor of the CBC Radio Orchestra. Bernardi’s career honours included the Order of Canada and the Governor General’s Performing Arts Award for Lifetime Achievement. The NAC plans to unveil a bust of Bernardi it commissioned from Canadian sculptor Ruth Abernethy on July 1 at the entrance of Southam Hall, where he led the orchestra in hundreds of concerts during his tenure [shown below]. The NAC says it will also create a fund in Bernardi’s name to commission new Canadian compositions for the orchestra.

|

MB: Yes. One can say the generalized thing,

that it’s organized sound, although some music that I know is very close to

exactly the opposite — chaotic. But if the chaos

is then resolved into something that has a structure or a form, I suppose

that is music, too. Why not? But I would like to think that music

is more than that. It’s the most wonderful gift to men from the gods,

as far as I’m concerned. When you think about it, it transcends words,

transcends matter. When you think of a composer sitting down from nothing

to create great work, a 40 minute symphony, how can that possibly happen?

Isn’t that a miraculous thing? At least a writer has a dictionary.

He can look up 100,000 words. A composer has twelve tones to rearrange,

repeat, and extend it and so on, but that’s all it is.

MB: Yes. One can say the generalized thing,

that it’s organized sound, although some music that I know is very close to

exactly the opposite — chaotic. But if the chaos

is then resolved into something that has a structure or a form, I suppose

that is music, too. Why not? But I would like to think that music

is more than that. It’s the most wonderful gift to men from the gods,

as far as I’m concerned. When you think about it, it transcends words,

transcends matter. When you think of a composer sitting down from nothing

to create great work, a 40 minute symphony, how can that possibly happen?

Isn’t that a miraculous thing? At least a writer has a dictionary.

He can look up 100,000 words. A composer has twelve tones to rearrange,

repeat, and extend it and so on, but that’s all it is. MB:

Sometimes there’s a germ of an idea. It could be something as simple

and unmusical as a date. Or sometimes — and I think this is wrong —

you have a famous artist or famous performer of some sort, and he or she is

famous for doing a certain piece, and you start from that. Somebody

is great at a certain composer, so you try and make a program that is varied

and that is somehow coherent, where the pieces fit with one another.

It’s quite a trick and it’s something that I enjoy very much.

MB:

Sometimes there’s a germ of an idea. It could be something as simple

and unmusical as a date. Or sometimes — and I think this is wrong —

you have a famous artist or famous performer of some sort, and he or she is

famous for doing a certain piece, and you start from that. Somebody

is great at a certain composer, so you try and make a program that is varied

and that is somehow coherent, where the pieces fit with one another.

It’s quite a trick and it’s something that I enjoy very much. MB: Oh, it can happen. It can happen that

in a couple of days you make them play in a certain way that is yours.

I conducted in San Francisco a couple of weeks ago, and there was a person

that works for a British record company. I was working with a couple

of singers, and they told me that in their tour they had had some bad experiences

with conductors and orchestras. So this record executive came after

the second rehearsal and said, “They sounded bloody marvelous!” I said,

“Well, it is a good orchestra.” “No, no,” she said. “I’ve heard

other good orchestras, and they sound really good. You make them sound

like a good orchestra.” I didn’t know what I did, but the singers were

quite happy and that’s the main thing, really. Yes, you can do it.

It’s very difficult to do here because of the physical situation. It’s

not the best. You’re out in the open and you have to get used to the

noises that you can’t do anything about, such as traffic, planes, birds.

But then to make matters worse, in the middle of the rehearsal this morning

a truck came. They were spraying water about forty feet from us, and

it was the loudest noise! I said, “Why can’t he go to the other side

of the park and start there? Come and do this side later.”

MB: Oh, it can happen. It can happen that

in a couple of days you make them play in a certain way that is yours.

I conducted in San Francisco a couple of weeks ago, and there was a person

that works for a British record company. I was working with a couple

of singers, and they told me that in their tour they had had some bad experiences

with conductors and orchestras. So this record executive came after

the second rehearsal and said, “They sounded bloody marvelous!” I said,

“Well, it is a good orchestra.” “No, no,” she said. “I’ve heard

other good orchestras, and they sound really good. You make them sound

like a good orchestra.” I didn’t know what I did, but the singers were

quite happy and that’s the main thing, really. Yes, you can do it.

It’s very difficult to do here because of the physical situation. It’s

not the best. You’re out in the open and you have to get used to the

noises that you can’t do anything about, such as traffic, planes, birds.

But then to make matters worse, in the middle of the rehearsal this morning

a truck came. They were spraying water about forty feet from us, and

it was the loudest noise! I said, “Why can’t he go to the other side

of the park and start there? Come and do this side later.”  BD:

Does this enter your psyche at all when you’re doing a live performance?

You think no one is taping it, and yet if you’re doing, say, a broadcast,

probably someone is taping off the radio somewhere.

BD:

Does this enter your psyche at all when you’re doing a live performance?

You think no one is taping it, and yet if you’re doing, say, a broadcast,

probably someone is taping off the radio somewhere.

MB:

The second performance is the most difficult, especially if the first performance

has gone very well. Then you really have to watch like mad. I

usually tell everybody at the second performance to be very careful, because

if you let down we know it.

MB:

The second performance is the most difficult, especially if the first performance

has gone very well. Then you really have to watch like mad. I

usually tell everybody at the second performance to be very careful, because

if you let down we know it.

MB: [Completely surprised] Why? [Laughs]

MB: [Completely surprised] Why? [Laughs] MB: I enjoy it,

and maybe I make too much of it, but the recitatives come almost like a leitmotif

opera. I like to quote other Mozart operas. I suppose this is

wrong, but for instance, in one of the very first or second recitatives of

Figaro and Susanna when they are having their two little duets and she says,

“The count is tired of this local adventure,” I play [sings] ya-pa-pa-pa-pa-pa-pom-pom-pom

[to the tune of Don Giovanni’s Serenade, shown at right].

MB: I enjoy it,

and maybe I make too much of it, but the recitatives come almost like a leitmotif

opera. I like to quote other Mozart operas. I suppose this is

wrong, but for instance, in one of the very first or second recitatives of

Figaro and Susanna when they are having their two little duets and she says,

“The count is tired of this local adventure,” I play [sings] ya-pa-pa-pa-pa-pa-pom-pom-pom

[to the tune of Don Giovanni’s Serenade, shown at right].

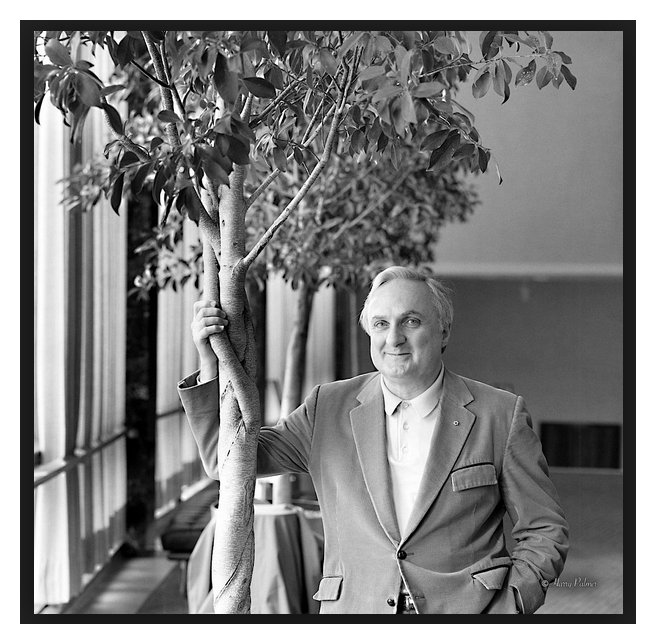

This conversation was recorded in Chicago on June 15, 1995.

Portions were broadcast on WNIB later that year, and again in 2000.

This transcription was made in 2015, and posted on this website at that

time.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website, click here.

Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM.

You are invited to visit his website for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.