A Conversation with Bruce Duffie

|

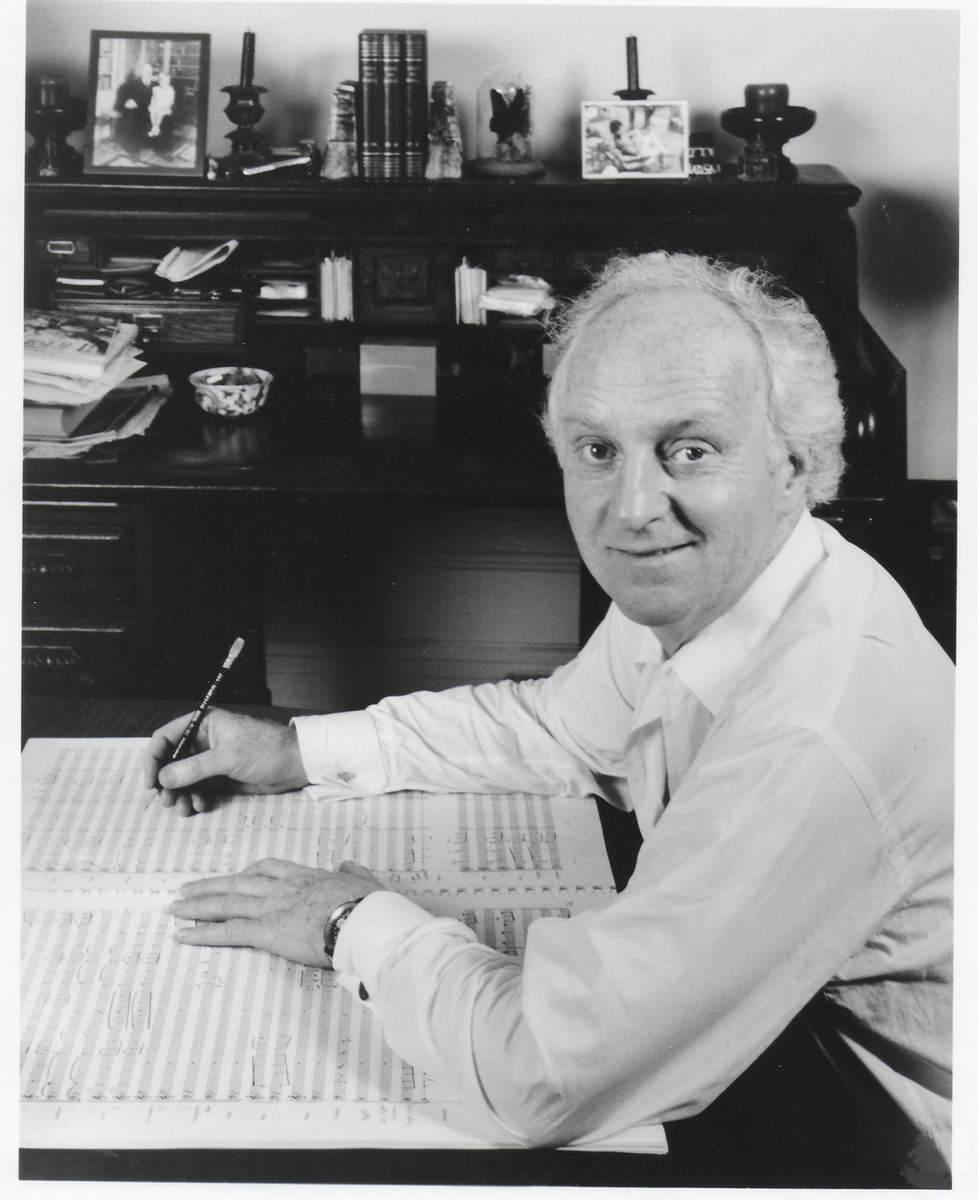

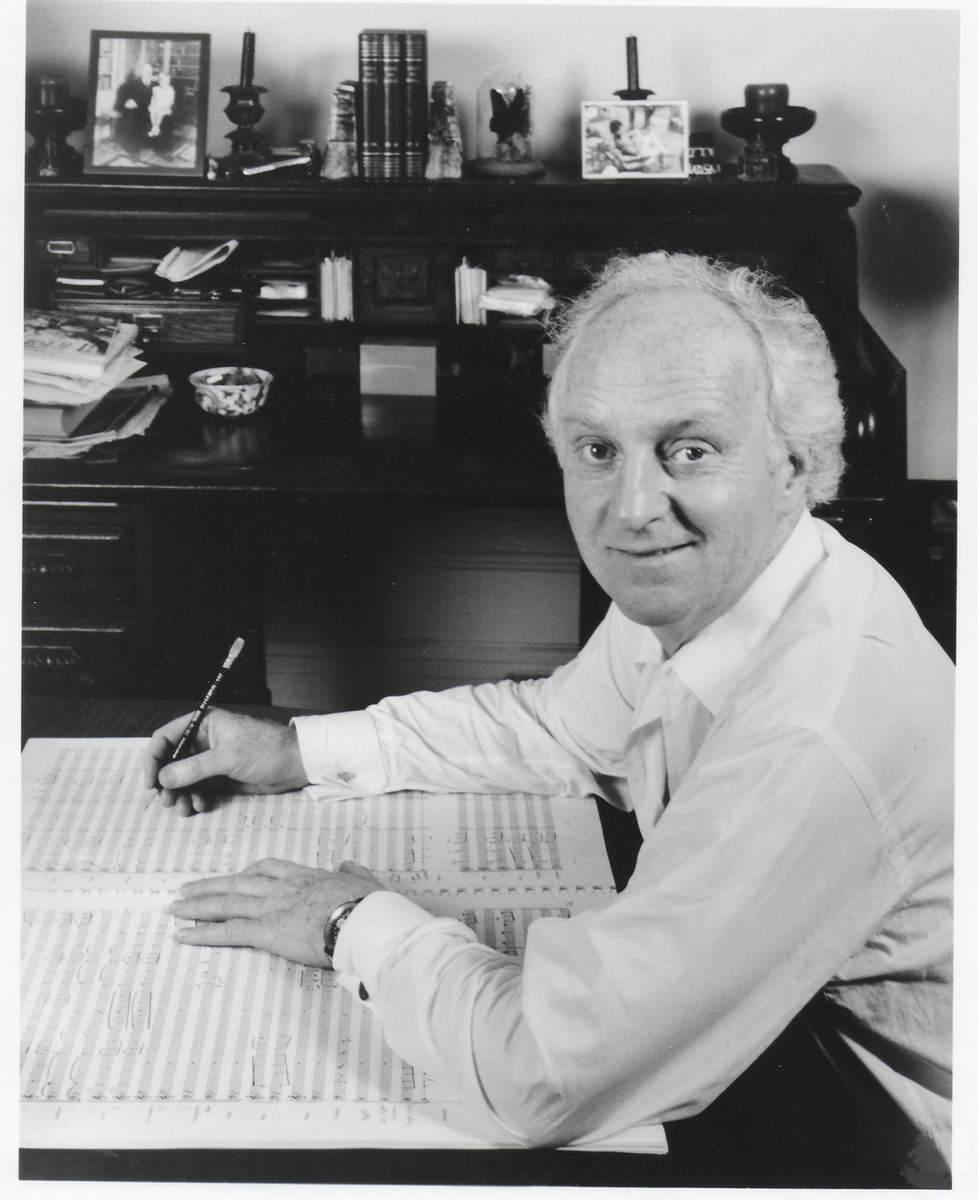

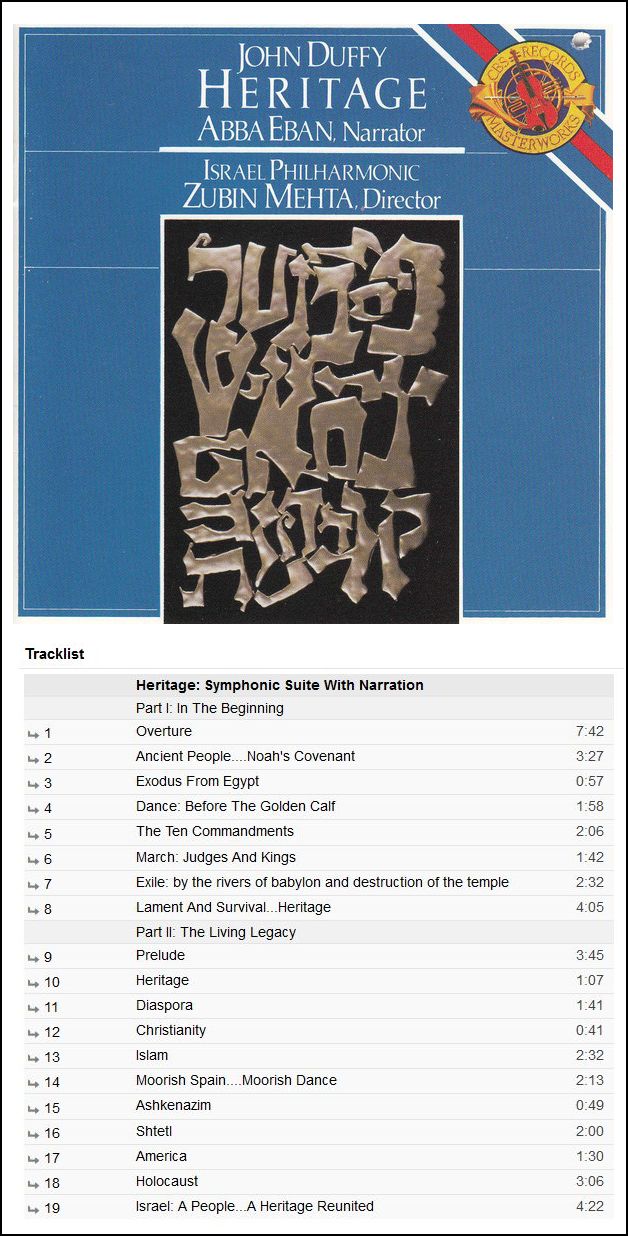

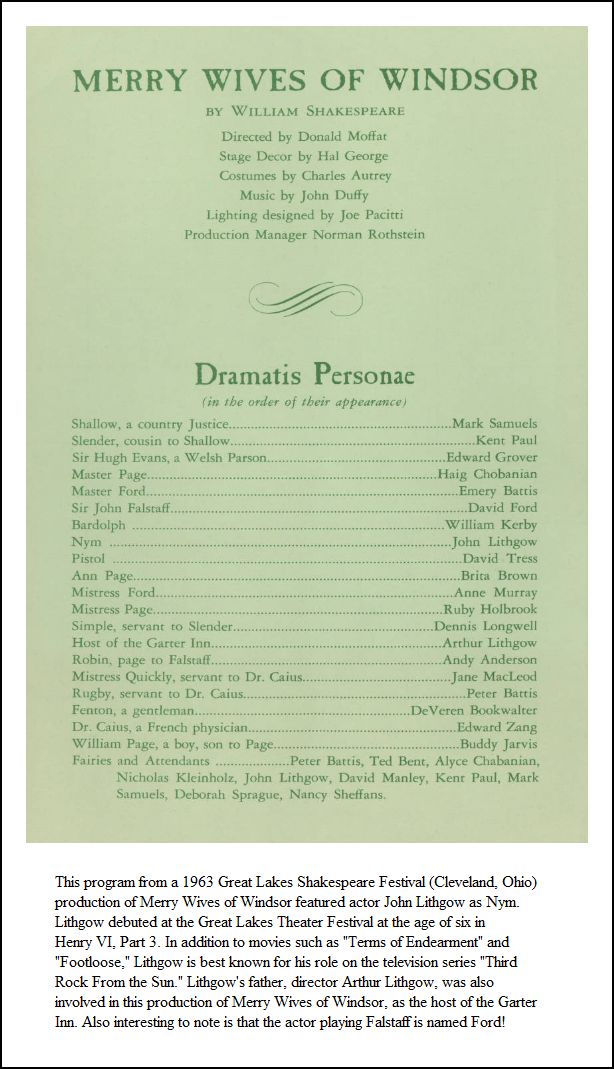

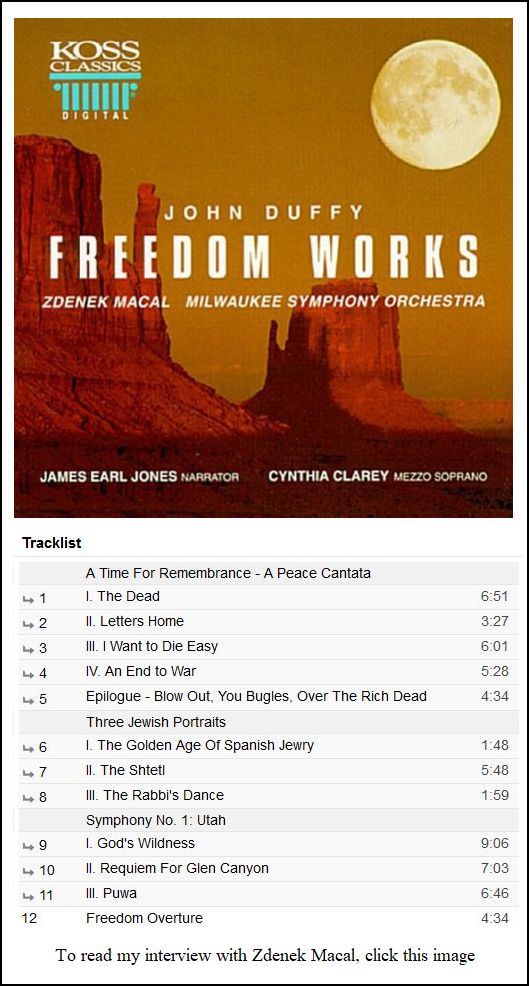

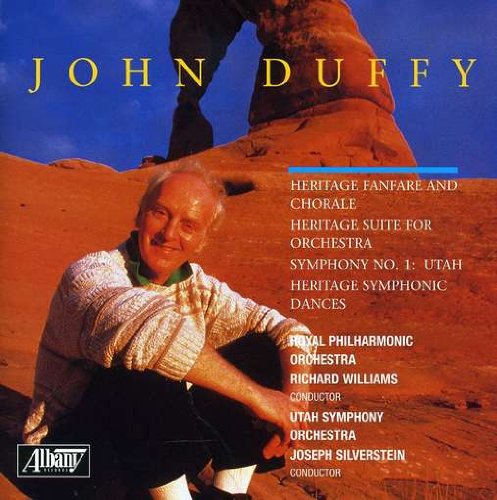

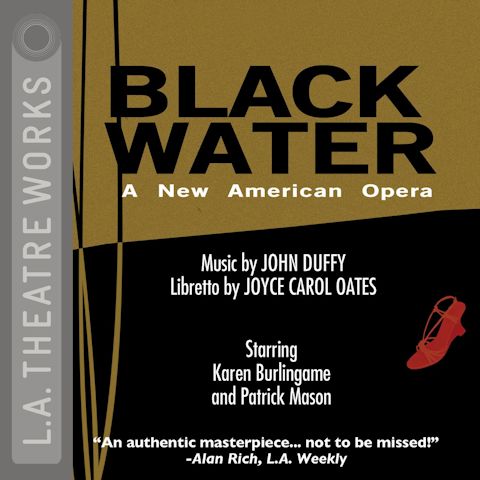

John Duffy (June 23, 1929 - December 22, 2015), considered "one of the great heroes of American music," has composed more than 300 works for symphony orchestra, opera, theater, television and film. He has received many awards for his contributions to music: two Emmys, an ASCAP award for special recognition in film and television music, a New York State Governor's Art Award, and the (New York City) Mayor's Award of Honor for Arts and Culture. He is also the recipient of the American Music Center's Founders' Award for Lifetime Achievement. As founder and president of Meet the Composer, an organization dedicated to the creation, performance, and recording of music by American composers, he initiated countless landmark programs to advance American music and to aid American composers. Duffy grew up in the Bronx, one of fourteen children of Irish immigrant parents. As a young man, he studied composition with noted composers Aaron Copland, Henry Cowell, Luigi Dallapiccola, Solomon Rosowsky and Herbert Zipper concurrently with his career and early successes in the theater. He credits Rosowsky for insisting uncompromisingly on learning the craft of music and developing the discipline and patience necessary to the art. His profound regard for language, its beauties and its powers, suited him ideally for his work in theater, television and film. He acquired a reputation early on as a first-class interpreter of ideas and emotion, a brilliant orchestrator, and a sensitive colleague. Duffy's appointment, in his twenties, to the post of music director, composer and conductor of Shakespeare under the Stars, was the first in a succession of similar posts at the Guthrie Theater, the Long Wharf Theatre, and the Vivian Beaumont Theater at Lincoln Center, and for NBC and ABC television in New York City. The culmination was his landmark music for the production of Macbeth at John Houseman's American Shakespeare Festival in Stratford, Connecticut. He composed some of his notable theater scores for Broadway and Off-Broadway productions of The Ginger Man, Macbird, Mother Courage, Playboy of the Western World, and many Shakespeare plays, including his memorable collaboration with John Houseman. Duffy also has composed distinguished concert music for a variety of commissions, among them: A Time for Remembrance (cantata for soprano, speaker and orchestra), commissioned by the U.S. Government to mark the 50th anniversary of the bombing of Pearl Harbor; Symphony No. 1: Utah, commissioned by the Sierra Club to draw attention to preserving and protecting public lands in southern Utah; Freedom Overture, commemorating the fall of the Berlin Wall; Concerto for Stan Getz and Concert Band; and the Emmy Award-winning score for the nine-hour PBS documentary, narrated by Abba Eban, "Heritage: Civilization and the Jews." The New York Times, the Wall Street Journal, and the Chicago Tribune call his music, "haunting, memorable, and brilliant." Recordings of his music appear on the CBS, Albany, L.A. TheatreWorks, and Koss labels. His most recent opera, Black Water, with a libretto by Joyce carol Oates, premiered in Philadelphia in 2001, followed by performances in Los Angeles, Lincoln Center and Cooper Union Hall in New York City, as well as performances in Maine. Mark Swed, chief music critic for the Los Angeles Times, said, "…at some point the listener no longer feels like a bemused bystander, watching yet another episode of a Washington soap opera, and becomes caught up in a real opera of universal tragedy. The ending is devastating – an excellent tonic for the nightly news." |

Duffy: I would say basically it was historical.

It’s political in the sense of the view of humanism, of great people,

small in number, who survived and who enriched humankind, and whose

contributions to humankind are part of our shared heritage.

In that sense it has a humanist point of view. It is political

in the sense that there are clearly opposing points of view about the

state of Israel — clearly a conflict

with the Arabs — and there

are various countries that take sides. It wasn’t focused in

that sense. The idea was to show the rise and struggle of the

people, and to show the effect of civilization on the people, and the

effect those people had on those cultures in which they lived. In

the case of the Jewish people, when they were dispersed

— the diaspora —

they went to all parts of the world. One of the most

astounding things in the series is something which, whenever I saw

it, just moved me very much. This was the opening shots where you

see a skyline of New York, and then suddenly the camera changes and you

see Rome and Florence. In Florence the camera picks up Michelangelo’s

David, and then it goes to Hasidic Jews dancing and singing. Then

you hear a number of cantors and rabbis reading from the Old Testament,

but in different languages — English,

Spanish, Chinese, Russian, Vietnamese, French, Portuguese

— and it doesn’t take you very long to

realize that this great prophetic tradition, this great inspirational

work — the Old Testament

— is something that we hold very dear, and which

has influenced all our lives and history. So in that sense, it’s

a-political. It’s more in a historical or philosophical sense.

It’s enlightened humanism.

Duffy: I would say basically it was historical.

It’s political in the sense of the view of humanism, of great people,

small in number, who survived and who enriched humankind, and whose

contributions to humankind are part of our shared heritage.

In that sense it has a humanist point of view. It is political

in the sense that there are clearly opposing points of view about the

state of Israel — clearly a conflict

with the Arabs — and there

are various countries that take sides. It wasn’t focused in

that sense. The idea was to show the rise and struggle of the

people, and to show the effect of civilization on the people, and the

effect those people had on those cultures in which they lived. In

the case of the Jewish people, when they were dispersed

— the diaspora —

they went to all parts of the world. One of the most

astounding things in the series is something which, whenever I saw

it, just moved me very much. This was the opening shots where you

see a skyline of New York, and then suddenly the camera changes and you

see Rome and Florence. In Florence the camera picks up Michelangelo’s

David, and then it goes to Hasidic Jews dancing and singing. Then

you hear a number of cantors and rabbis reading from the Old Testament,

but in different languages — English,

Spanish, Chinese, Russian, Vietnamese, French, Portuguese

— and it doesn’t take you very long to

realize that this great prophetic tradition, this great inspirational

work — the Old Testament

— is something that we hold very dear, and which

has influenced all our lives and history. So in that sense, it’s

a-political. It’s more in a historical or philosophical sense.

It’s enlightened humanism. Duffy: [Laughs] That’s a wonderful question!

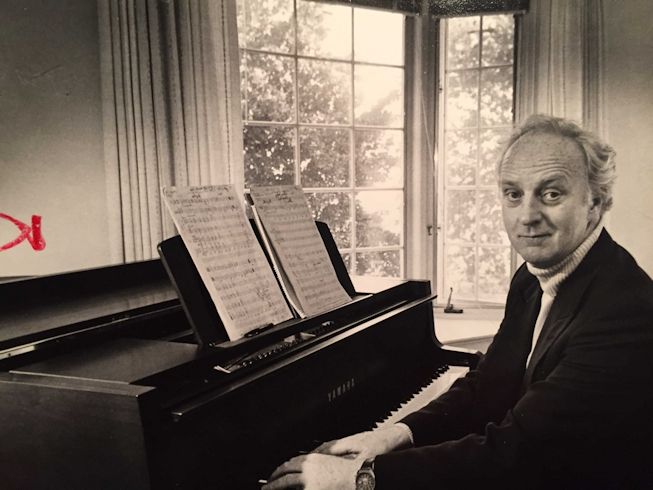

I go about writing music in a very emotional and physical way.

I spend an enormous amount of time working at the piano

— not that I write at the piano, but I try

things out. I walk around the street, and I hum them.

I digest that music, but in an emotional way. I don’t sit down

and formulate it in an intellectual way, although I have technique, and

I have a great deal of musical resources. I approach things emotional

and physically, so, in a sense I do both of what you ask

— the project brings the music out of me, and

I bring the music to the project. Perhaps all composers work that

way. Some composers tend to approach the writing of music in

a more analytical way first of all. I’m just paraphrasing what he

said, but Einstein is interesting because people believe that he actually

intuited the theory of relativity, and it was after he intuited this

that he gathered the knowledge and the formula, and analyzed it, and

therefore could say, “This is what it is.”

Duffy: [Laughs] That’s a wonderful question!

I go about writing music in a very emotional and physical way.

I spend an enormous amount of time working at the piano

— not that I write at the piano, but I try

things out. I walk around the street, and I hum them.

I digest that music, but in an emotional way. I don’t sit down

and formulate it in an intellectual way, although I have technique, and

I have a great deal of musical resources. I approach things emotional

and physically, so, in a sense I do both of what you ask

— the project brings the music out of me, and

I bring the music to the project. Perhaps all composers work that

way. Some composers tend to approach the writing of music in

a more analytical way first of all. I’m just paraphrasing what he

said, but Einstein is interesting because people believe that he actually

intuited the theory of relativity, and it was after he intuited this

that he gathered the knowledge and the formula, and analyzed it, and

therefore could say, “This is what it is.” Duffy: Obviously a true voice, an original voice,

and by ‘original’ I

don’t mean someone who is doing something avant-garde, or radical just

to do it that way. That doesn’t make it original. One could

be writing a very simple melody, or using harmony or rhythm in a very

dramatic way, or in a somewhat traditional way and still be original.

You have to have an original voice, and you also have to write music

that moves people, that engages them. It doesn’t matter if it’s

symphonic music, or a song. If you think of our own time, I often

think of various songs by Stevie Wonder. You find them very engaging.

The melodies are catching, the story is something that you can

respond to, and the music is built up in such a way that it’s almost

like a Schubert song. It develops, and it expresses ideas very

often in an oblique way so that it’s surprising. It doesn’t

hit you over the head. Coming back to generalities, for music

to have stature, or to be great, the composer has to feel an enormous

belief in what he or she is doing, and it has to consummate craftsmanship,

and be able to express the idea in the most consummate way. There

are composers whose craft was so great that it freed them to express

the most sublime feelings. Bach is one of them. His craft

was so extraordinary. Mozart was another. On my way out

here to Chicago, I was listening to a recording of The Marriage of

Figaro. By the way, it’s interesting that in Mozart’s

time they loved it as much as people love it today. What’s

extraordinary about that opera are the little touches. Even in

the overture, and in the first scene where Figaro is measuring the bed,

these little pieces of technique come. They’re very subtle and,

if you’re a musician, you pick them up generally. A lay person may

not pick them up, but they know that something wonderful is happening,

and that’s the sense of detail and care. Someone has said that God

is in the detail, and I guess in the case of Mozart and Bach, you couldn’t

argue about that.

Duffy: Obviously a true voice, an original voice,

and by ‘original’ I

don’t mean someone who is doing something avant-garde, or radical just

to do it that way. That doesn’t make it original. One could

be writing a very simple melody, or using harmony or rhythm in a very

dramatic way, or in a somewhat traditional way and still be original.

You have to have an original voice, and you also have to write music

that moves people, that engages them. It doesn’t matter if it’s

symphonic music, or a song. If you think of our own time, I often

think of various songs by Stevie Wonder. You find them very engaging.

The melodies are catching, the story is something that you can

respond to, and the music is built up in such a way that it’s almost

like a Schubert song. It develops, and it expresses ideas very

often in an oblique way so that it’s surprising. It doesn’t

hit you over the head. Coming back to generalities, for music

to have stature, or to be great, the composer has to feel an enormous

belief in what he or she is doing, and it has to consummate craftsmanship,

and be able to express the idea in the most consummate way. There

are composers whose craft was so great that it freed them to express

the most sublime feelings. Bach is one of them. His craft

was so extraordinary. Mozart was another. On my way out

here to Chicago, I was listening to a recording of The Marriage of

Figaro. By the way, it’s interesting that in Mozart’s

time they loved it as much as people love it today. What’s

extraordinary about that opera are the little touches. Even in

the overture, and in the first scene where Figaro is measuring the bed,

these little pieces of technique come. They’re very subtle and,

if you’re a musician, you pick them up generally. A lay person may

not pick them up, but they know that something wonderful is happening,

and that’s the sense of detail and care. Someone has said that God

is in the detail, and I guess in the case of Mozart and Bach, you couldn’t

argue about that. BD: You’re responsible for Meet the Composer.

How do you decide which composers are going to get met?

BD: You’re responsible for Meet the Composer.

How do you decide which composers are going to get met?| Among the composers represented

in this series (some multiple times) are John Adams, John Harbison, Joan Tower, David Del Tredici, Bernard Rands, Donald Erb, Daniel Asia,

Robert Beaser,

Joseph Schwantner,

Libby Larsen,

Stephen Paulus,

Charles Wuorinen,

William Kraft,

Christopher

Rouse, Alvin Singleton, Tobias Picker, Dan Welcher,

John Corigliano;

conductors Edo de Waart, André Previn,

Leonard Slatkin,

Zubin Mehta, Riccardo Muti, Gerard Schwarz, James

Sedares, Dennis Russell

Davies, Sir Neville Marriner, Herbert Blomstedt,

Paul Polivnik, Christopher Wilkins, David Zinman, Robert Shaw, Louis Lane,

Sergiu

Comissiona, Donald Johanos, Daniel Barenboim;

and performers Susan Larson, Lynn Harrell, Lucy Shelton,

Ursula Oppens,

Garrick Ohlsson, Leona Mitchell. |

Duffy: That has come up, and it’s

a very astute question. It’s generally come up from composers

who have not been asked yet. However, the music director is

more about carrying out their responsibility. In earlier days,

their responsibility was to know, like Koussevitzky knew, who the

heck was writing music that had something to say, and perform it. They

had to not only know, but tell the audience when the audience felt nervous

that it’s okay. “This is someone who has

something to say, and I’m going to play it for you once, and you’ll listen,

and then I’m going to play it again, because I think you’ll like it even

better the second time.” [Both laugh] But

in this age, where music directors are not at home very much, where

they’re traveling a great deal, and there’s this enormous amount of

competition for these posts, music directors simply don’t do that.

I’m not saying this in a judgmental way, but take the reality that you

have here in Chicago, for instance. You have a great master [Sir Georg Solti] who

spends just six or eight weeks here. He doesn’t learn many new works

because he learns music thoroughly. So, he may learn a couple

of new works a year. What could be better for him but to have a

composer who knows what’s going on, a composer with whom he feels a

rapport, some simpatico, a composer he trusts and whose work he admires.

That’s the number one thing. He must admire that composer’s

work and believe in that composer so much that he wants to nurture and

perform his or her work, in the same way that Reiner did for Bartók,

and Stokowski did for any number of composers, and like Koussevitzky also

did.

Duffy: That has come up, and it’s

a very astute question. It’s generally come up from composers

who have not been asked yet. However, the music director is

more about carrying out their responsibility. In earlier days,

their responsibility was to know, like Koussevitzky knew, who the

heck was writing music that had something to say, and perform it. They

had to not only know, but tell the audience when the audience felt nervous

that it’s okay. “This is someone who has

something to say, and I’m going to play it for you once, and you’ll listen,

and then I’m going to play it again, because I think you’ll like it even

better the second time.” [Both laugh] But

in this age, where music directors are not at home very much, where

they’re traveling a great deal, and there’s this enormous amount of

competition for these posts, music directors simply don’t do that.

I’m not saying this in a judgmental way, but take the reality that you

have here in Chicago, for instance. You have a great master [Sir Georg Solti] who

spends just six or eight weeks here. He doesn’t learn many new works

because he learns music thoroughly. So, he may learn a couple

of new works a year. What could be better for him but to have a

composer who knows what’s going on, a composer with whom he feels a

rapport, some simpatico, a composer he trusts and whose work he admires.

That’s the number one thing. He must admire that composer’s

work and believe in that composer so much that he wants to nurture and

perform his or her work, in the same way that Reiner did for Bartók,

and Stokowski did for any number of composers, and like Koussevitzky also

did. BD: And a nice man too!

BD: And a nice man too! Duffy: Right.

Duffy: Right. Duffy: I was born June 23rd, 1929.

Duffy: I was born June 23rd, 1929.

| The New Philharmonic Orchestra was

founded in 1977, when the College of DuPage boldly embarked on sponsoring

resident professional arts organizations. Since its first concert that

November, when an orchestra of 24 carefully auditioned musicians performed

for a capacity audience of 330 in the Building M open space on west campus,

the New Philharmonic has expanded and thrived. Now under the direction

of Artistic Director and Conductor Kirk Muspratt, the orchestra numbers

approximately 60 players, depending on the repertoire, and performs for

audiences of 1,500 people per engagement in the beautiful McAninch Arts

Center. Under Muspratt’s direction, the orchestra performs innovative

renditions of classic and modern works. [To read a detailed biography

of Kirk Muspratt, and an article about Harold Bauer, who formed

the orchestra, click here.] The New Philharmonic is the only professional orchestra based in DuPage County, Illinois, and is grateful to call the MAC its home. The college provides substantial in-kind support. Funding comes from ticket sales, corporate and individual donations, grants, the Illinois Arts Council, DuPage Community Foundation, JCS Fund, College of DuPage Foundation, and from the college’s Student Activities Fund. |

© 1988 Bruce Duffie

This conversation was recorded in suburban Chicago on January 25, 1988. Portions were broadcast on WNIB in 1993 and 1998. This transcription was made in 2020, and posted on this website at that time. My thanks to British soprano Una Barry for her help in preparing this website presentation.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website, click here. To read my thoughts on editing these interviews for print, as well as a few other interesting observations, click here.

Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM, as well as on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio.

You are invited to visit his website for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.