BD: There were always a few performances,

but it seems now there’s a much bigger resurgence, or is that just perception?

BD: There were always a few performances,

but it seems now there’s a much bigger resurgence, or is that just perception? DD:

All my life, probably because I was trained as a violinist and piano was

secondary. Violinists or other instrument players, if they’re composers

they usually work that way. Pianists, I think, in our time have the

worst compositional techniques, because they don’t hear linearly.

DD:

All my life, probably because I was trained as a violinist and piano was

secondary. Violinists or other instrument players, if they’re composers

they usually work that way. Pianists, I think, in our time have the

worst compositional techniques, because they don’t hear linearly. DD:

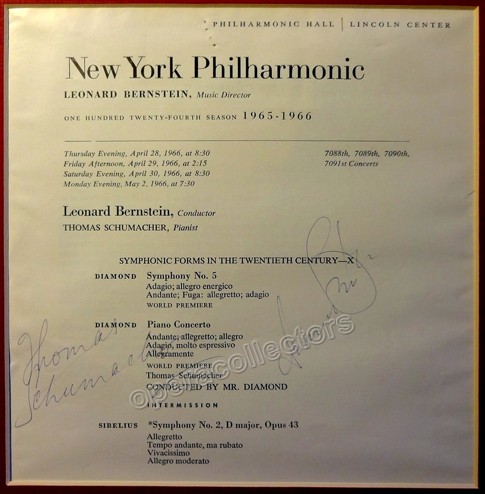

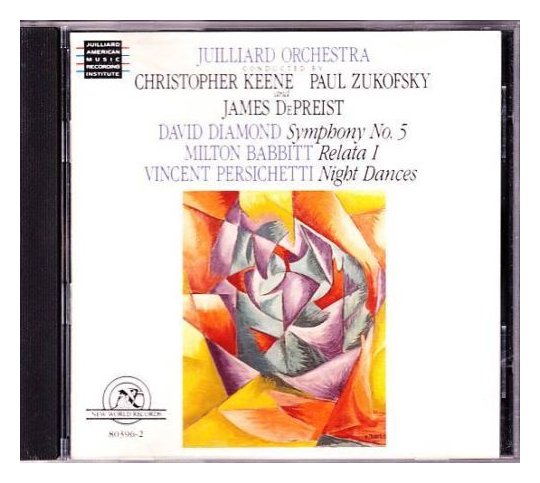

They’ve tried and they can’t because the music is so contrapuntal.

For example, the Fifth Symphony

that’s being done here would be impossible to arrange for band because

of the big fugue that ends it. It also has a huge organ climax which

is not available to the band. [Both laugh]

DD:

They’ve tried and they can’t because the music is so contrapuntal.

For example, the Fifth Symphony

that’s being done here would be impossible to arrange for band because

of the big fugue that ends it. It also has a huge organ climax which

is not available to the band. [Both laugh] BD: Of course, there’s the text and a

scenario.

BD: Of course, there’s the text and a

scenario. DD: That is one of the most tragic things

that has happened in music, and in Europe it has not stopped. They’re

still losing all that, because there, music—all art—is subsidized by governments.

So you have Mr. Stockhausen still knocking everybody’s heads off with so

much sound, they go mad. None of his works of the past have gone

into the repertoire. You know, when a composer has been around as

long as Stockhausen, and not three pieces, not even the piano pieces, are

taken up by anyone and played again, it’s a rather sad commentary.

DD: That is one of the most tragic things

that has happened in music, and in Europe it has not stopped. They’re

still losing all that, because there, music—all art—is subsidized by governments.

So you have Mr. Stockhausen still knocking everybody’s heads off with so

much sound, they go mad. None of his works of the past have gone

into the repertoire. You know, when a composer has been around as

long as Stockhausen, and not three pieces, not even the piano pieces, are

taken up by anyone and played again, it’s a rather sad commentary. BD: Now when you say, “every human being on

the earth,” I assume you’re acknowledging a basic understanding of the

Western Musical Language?

BD: Now when you say, “every human being on

the earth,” I assume you’re acknowledging a basic understanding of the

Western Musical Language? BD: Who’s right?

BD: Who’s right? DD: I’ve written over a hundred and something

songs, and lots of them have gone into singers’ repertoire. I always

feel comfortable with the voice, and it’s always wonderful when you find

the right poetry to write songs. But I haven’t been able to do too

many of them because as I got older and older, I found it takes longer

and longer to write music. You develop physical ailments and your

eyes get bad and it just takes longer. The physical labor is horrendous!

It’s tough going.

DD: I’ve written over a hundred and something

songs, and lots of them have gone into singers’ repertoire. I always

feel comfortable with the voice, and it’s always wonderful when you find

the right poetry to write songs. But I haven’t been able to do too

many of them because as I got older and older, I found it takes longer

and longer to write music. You develop physical ailments and your

eyes get bad and it just takes longer. The physical labor is horrendous!

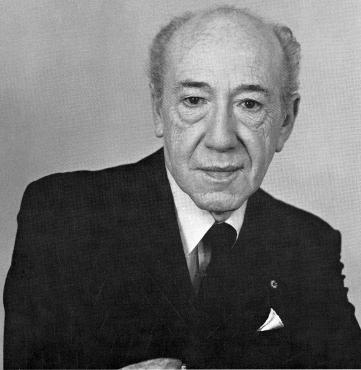

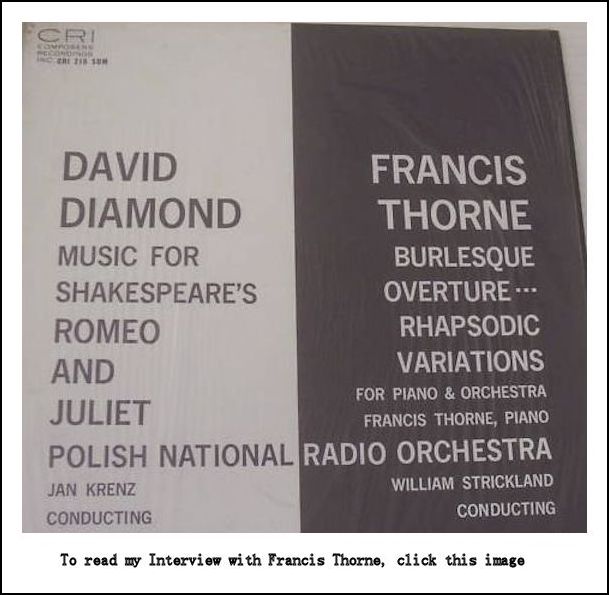

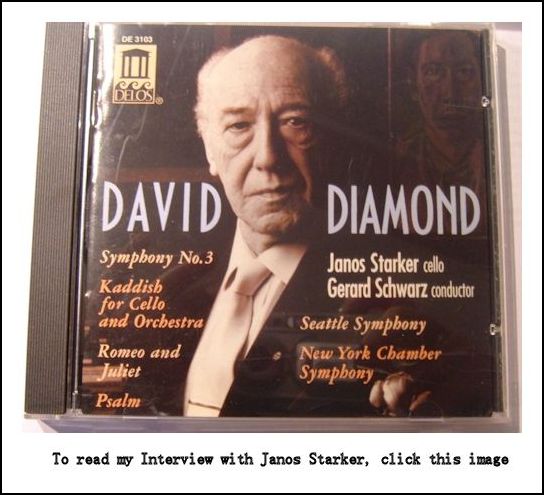

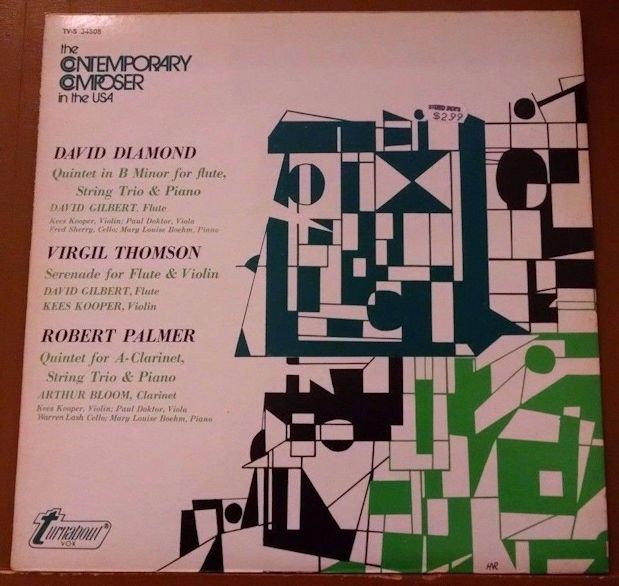

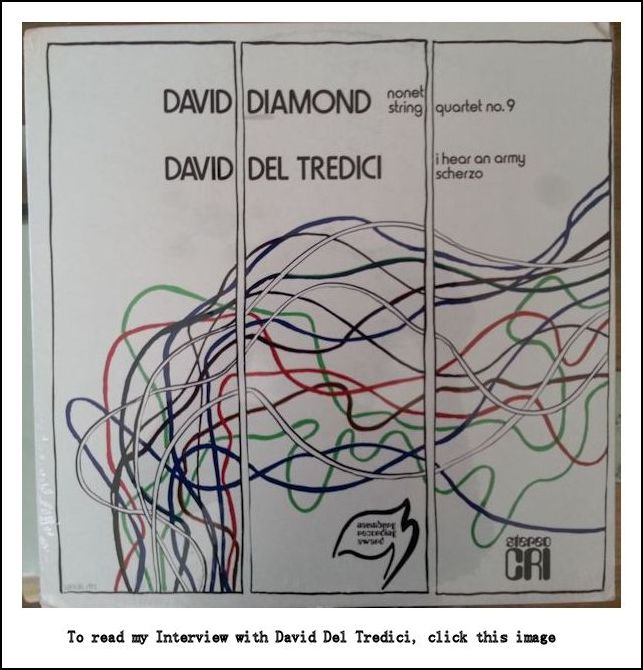

It’s tough going.David Diamond was born on July 9, 1915, in Rochester, New York. He received his first formal training at the Cleveland Institute of Music. In 1930 he continued his studies at the Eastman School with Bernard Rogers in composition and Effie Knauss in violin. In the fall of 1934 he went to New York on a scholarship from the New Music School and Dalcroze Institute, studying with Paul Boepple and Roger Sessions until the spring of 1936. That summer, Diamond was commissioned to compose the music for the ballet TOM to a scenario by E.E. Cummings based on "Uncle Tom's Cabin." Leonide Massine, the choreographer for the ballet, lived near Paris, and Diamond was sent there to be near him. Although, due to financial problems, the work was never performed, Diamond did establish contacts in Paris with Darius Milhaud, Albert Roussel, and the composer he revered above all others, Maurice Ravel. (The First Orchestral Suite from the ballet TOM received its much belated and much acclaimed premiere in 1985, conducted by Gerard Schwarz). On his second visit to Paris in 1937, Diamond joined the class of Nadia Boulanger at Fontainebleau. He was introduced to Igor Stravinsky, who listened to a four-hand piano version of Diamond's just-written Psalm for orchestra. With a few revisions based on Stravinsky's appraisal, Psalm won the 1937 Juilliard Publication Award, and was among the compositions influencing his receipt of a Guggenheim Fellowship in 1938. After the San Francisco premiere of Psalm under Pierre Monteux, Alfred Frankenstein wrote: "On first hearing, the outstanding qualities of this work seem to be its fine, granitic seriousness, its significant compression of a large idea into a small space, and its spare, telling use of the large orchestra." Upon Ravel's death in 1937, Diamond wrote an Elegy for brass, percussion and harps (later arranged for strings and percussion), dedicated to the memory of the composer who had been his ideal. Diamond spent 1938-39 in Paris on his Guggenheim Fellowship. He returned to the United States when Germany declared war on France, and the problems of day-to-day existence in America soon replaced the charmed life of the gifted young composer in France. He worked as a night clerk at a soda counter in New York City, and after resuming violin practice, did a two year stint in the "Hit Parade" radio orchestra. An impressive number of awards and commissions during the 1940s somewhat relieved Diamond's struggle for daily needs. Among the awards was a renewal of the Guggenheim Fellowship, the Prix de Rome, a personal commission from Dimitri Mitropoulos (resulting in the popular Rounds for string orchestra), a commission from the Koussevitzky Foundation for his Symphony No. 4, and a National Academy of Arts and Letters Grant "in recognition of his outstanding gift among the youngest generation of composers, and for the high quality of his achievement as demonstrated in orchestral works, chamber music, and songs." Important works appearing during the 1940s include the Concerto for Two Solo Pianos (1942), String Quartet No. 2 (1943), Symphony No. 3 (1945), String Quartet No. 3 (1946, receiving the 1947 New York Music Critics' Circle Award), Sonata for Piano (1947) and Chaconne for Violin and Piano (1948). In the 1950s Diamond's music became imbued with a much more chromatic texture. A good example of this new chromaticism is The World of Paul Klee, four scenes inspired by paintings of the Swiss artist. Irving Kolodin praised Diamond's "orchestral concept, his refinement of touch, and power of imagery" in this work. The String Quartet No. 4, written in 1951, was nominated for a Grammy award in 1965, as recorded on Epic Records by the Beaux Arts Quartet. Alfred Frankenstein called the work "one of the masterpieces of modern American chamber music.... The fugal movement provides one of the most moving experiences to be found in the whole range of modern American music, but the entire work is an achievement of the rarest quality." In 1951 Diamond returned to Europe as Fulbright Professor. Peermusic signed him to an exclusive contract in 1952, which enabled him to remain in Europe, eventually settling in Florence, Italy. Except for brief visits to the United States, such as the occasion of his appointment as Slee Professor at the University of Buffalo in 1961 and again in 1963, he remained in Italy until 1965, when he returned to the United States. On his return, Diamond was greeted by a series of concerts around the country commemorating his fiftieth birthday. The New York Philharmonic performed two of his major orchestral works, the Symphony No. 5, with Leonard Bernstein conducting, and the Piano Concerto, conducted by Mr. Diamond himself. Harriet Johnson wrote of the fifth symphony that "its rich texture, glowing from an expansive imagination, soars with a pulsation that is improvisatory but at the same time the essence of formal logic and economy of structure." Leonard Bernstein was even more enthusiastic, finding the fifth symphony "his finest and most concentrated symphonic work to date. But even more important, I find it to be a work that revives one's hopes for the symphonic form." Bernstein praised the "seriousness, intelligence, weight, deftness, technical mastery, and sheer abundance" of Diamond's music, calling him "a vital branch in the stream of American Music." From 1965 to 1967 Diamond taught at the Manhattan School of Music. During these two years he was the recipient of several awards, among them the Rheta Sosland Chamber Music prize for his String Quartet No. 8, the Stravinsky ASCAP award, and election to the National Institute of Arts and Letters. In 1971, Diamond was given a National Opera Institute Grant to write his opera The Noblest Game. With a libretto by Katie Louchheim, The Noblest Game is the story of social intrigue in the Washington DC power set, taking place in the present, "after the termination of a recent war." Any portrait of David Diamond would not be complete without mention of his vocal music. Diamond's songs for voice and piano are among his finest achievements, sung by the likes of Jennie Tourel, Eileen Farrell, and Eleanor Steber. Hans Nathan has stated that "David Diamond has cultivated the art-song more consistently than any other American composer of his stature. Each of his songs is constructed with the same detailed care that is ordinarily given to an instrumental work." Diamond became professor of composition at The Juilliard School in 1973, where he taught well into the 1990s. The renewed interest in Diamond's music starting in the 1980s coincided with his being awarded some of the most significant honors available to a composer. In 1986, Diamond received the William Schuman Lifetime Achievement Award. In 1991 he was awarded the Gold Medal of the American Academy of Arts and Letters and the Edward MacDowell Gold Medal for Lifetime Achievement. Then, in 1995, he was a recipient of the National Medal of Arts in a ceremony at the White House. This period culminates in his largest symphony to date. The Symphony No. 11 (1989-91) was one of a few major works commissioned by the New York Philharmonic in celebration of its 150th anniversary. In his New York Times review, Alex Ross wrote that "the confidence and conviction of the voice are unmistakable" -- a phrase that applies to so much of Diamond's music written over a remarkable sixty year career. For more information about David Diamond's life and music, please visit David Diamond.org -- Biography from the Peermusic

website

|

This was my second interview with David Diamond. The first was

done on the telephone in April of 1986. This second interview, which

is presented on this page, was recorded in his hotel in Chicago on October

18, 1990. Portions (along with recordings) were used on WNIB in 1995

and 2000, on WNUR in 2005 and 2009, and on Contemporary Classical Internet

Radio in 2006 and 2010. The transcription was made and posted on this

website early in 2013. As with all my posted interviews, it differs

slightly from the original, having been edited to read smoothly and to tighten

where needed. I mention this because unbeknownst to me until I stumbled

upon it during a Google search, the audio of the copy I sent to Diamond at

his request has appeared on YouTube.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website, click here. To read my thoughts on editing these interviews for print, as well as a few other interesting observations, click here.

Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM, as well as on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio.

You are invited to visit his website for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.