A Conversation with Bruce Duffie

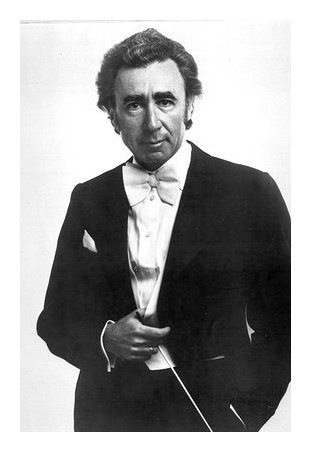

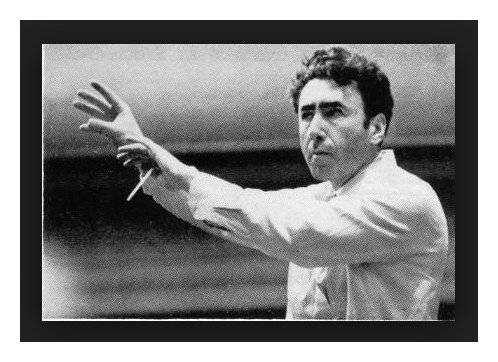

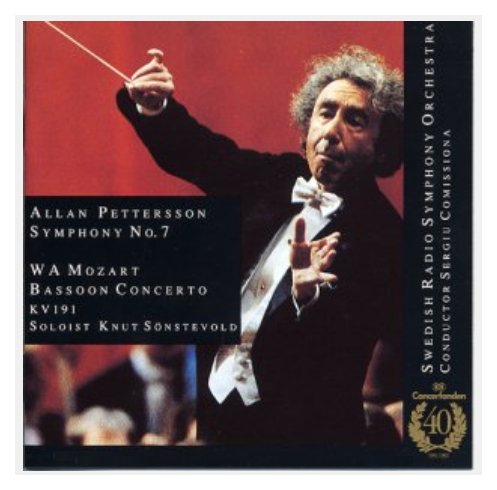

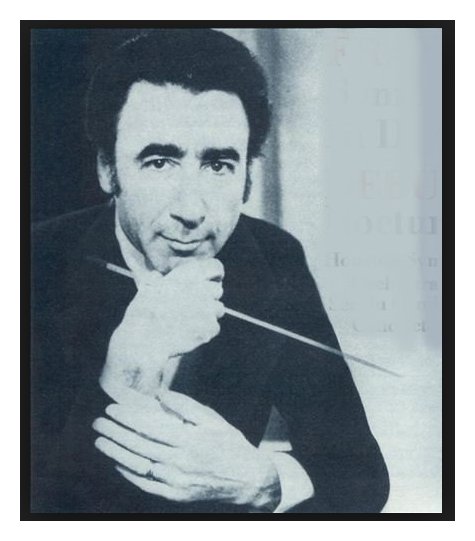

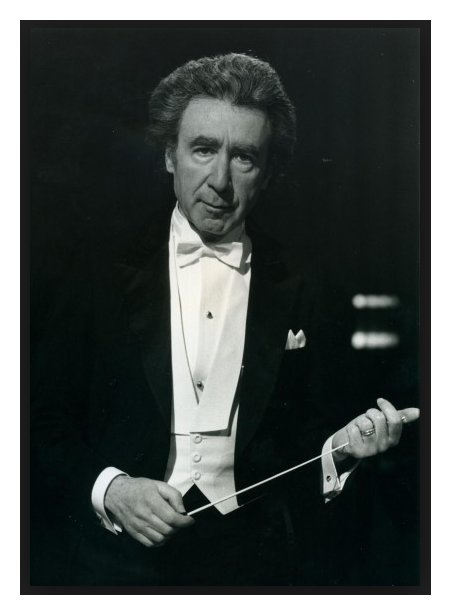

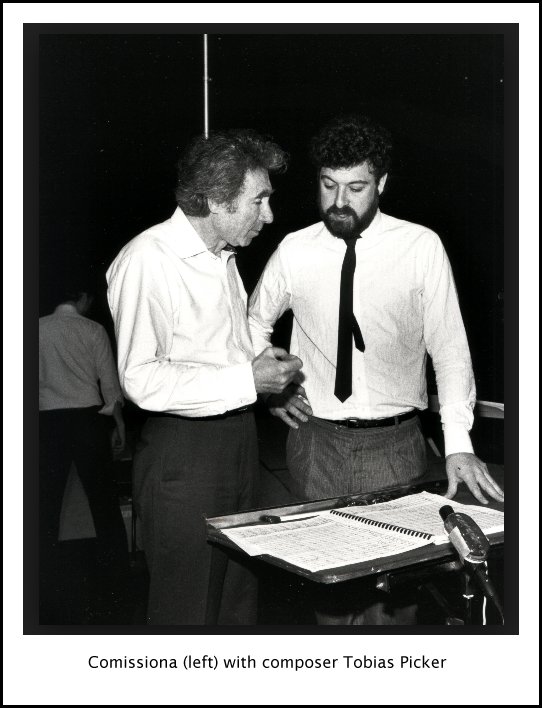

| Sergiu Comissiona was one of the

world's best-travelled conductors, a welcome guest with orchestras the world

around - though it was in America that he made his deepest impression. He

was, in the words of Stephen Cera, music critic of The Baltimore Sun in the latter part of

the 25 years Comissiona spent with the orchestra there, "an instinctive and

intuitive rather than intellectual conductor, emotionally generous in big

Romantic scores, wonderfully adept at achieving coloristic nuances. He preferred

a light, transparent sound; under him, the Baltimore Symphony was the orchestral

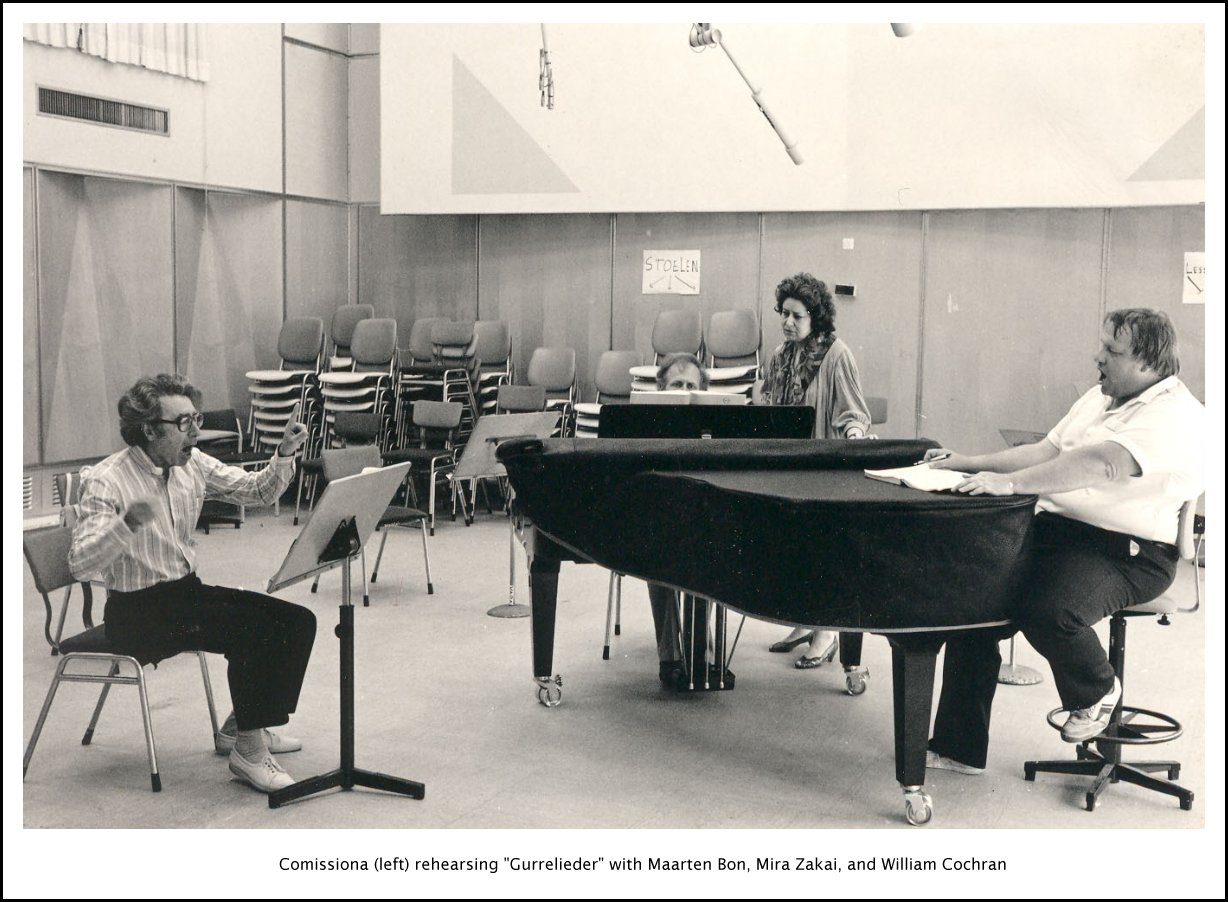

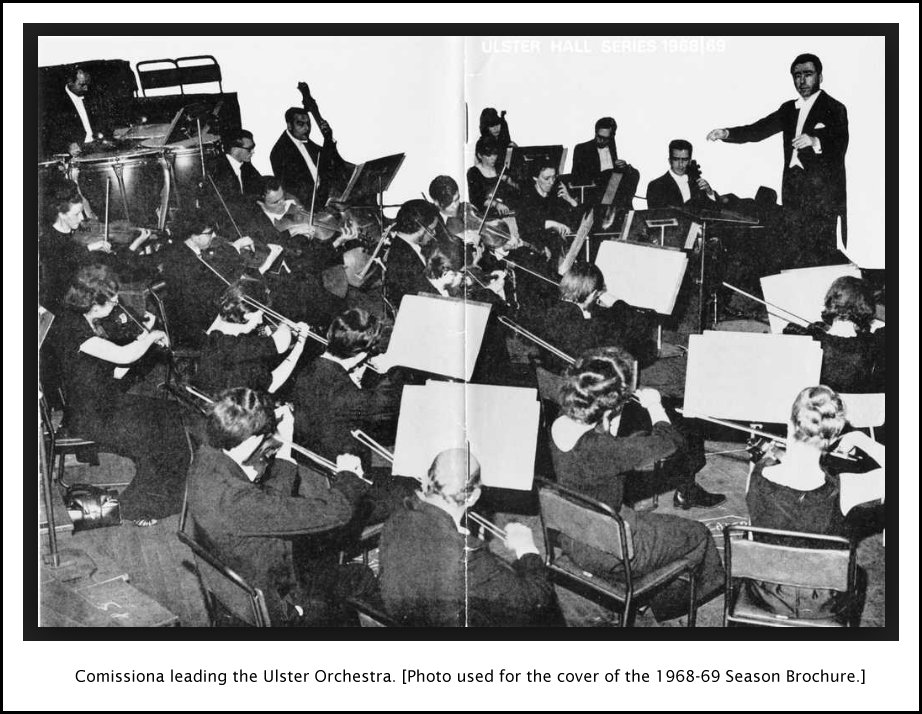

equivalent of a lovely and warm lyric soprano." Comissiona was born in Bucharest in 1928, into a musical family, and began studying the violin at five. Conducting beckoned early: he studied with Constantin Silvestri and Edouard Lindenberg and made his début at only 17, stepping in as a substitute to take over a performance of Gounod's Faust in Sibiu. In 1946, as a violinist, he joined the Bucharest Radio Quartet and in 1947 the Romanian State Ensemble. In an interview 40 years later he recalled his path to the podium, "From seven years, I started to go to concerts, collecting autographs and preparing the scores for the concert during the week and, of course, dreaming that the conductor would be sick. Then I would jump on the stage, make my début and I would be famous. It did happen, with the Romanian State Ensemble - without poisoning the conductor." He held the assistant conductorship of the ensemble for two years (1948-50) and was its music director for the next five; from 1955 until 1959 he was principal conductor of the Romanian State Opera. International attention had come in 1956, when he won the conducting competition in Besançon. Romania was not to hold on to Comissiona for much longer, either: being Jewish, he emigrated to Israel and took Israeli citizenship in 1959. He made his mark in his new homeland, serving as chief conductor of the Haifa Symphony Orchestra from 1960 to 1966. In 1960, too, he founded the Ramat Gan Chamber Orchestra, directing it until 1967. During this period he was a frequent visitor to Britain, appearing first with the London Philharmonic Orchestra in 1960 and then as a guest conductor of the Royal Ballet at Covent Garden between 1962 and 1966 - his spirited gestures allying themselves naturally to the choreographic movement on stage. Comissiona was first heard in his next adoptive country, the United States, in 1963, conducting the Israel Chamber Orchestra on tour; two years later he was invited to appear as guest conductor with the Philadelphia Orchestra. Other invitations began to arrive regularly, the long tenures which resulted giving an indication of how much his secure musicianship was appreciated: he was music director of the Gothenburg Symphony Orchestra for 11 years from 1966 (with 1967-68 as music adviser of the recently founded BBC Northern Ireland Orchestra in Belfast) and in 1969 he began his long relationship with the Baltimore Symphony Orchestra. He conducted a staggering 874 concerts in Baltimore, 21 of them including world premieres. He took the orchestra on its first foreign tour, to Mexico, in 1979, and two years later they toured the two Germanies, when the Baltimore Symphony became the first American orchestra to be invited to the Dresden music festival. His adventurous programming brought 271 works to Baltimore for the first time, and the BSO made its first recordings under him. Stephen Wigler, music critic for The Baltimore Sun during the early part of his time in Maryland, put it bluntly: "The modern Baltimore Symphony was created by Sergiu Comissiona." Comissiona and his wife, Robinne, also of Romanian origin, took their American citizenship with style - on the very day of the Bicentennial, 4 July 1976, at a special ceremony at Fort McHenry on Baltimore Harbor, itself a place of particular significance: it was the defence of Fort McHenry against the British in September 1814 that inspired Francis Scott Key to write "The Star-Spangled Banner". Sergiu Comissiona was active in the opera house as well as on the orchestral podium. He returned to Covent Garden - for Rossini's Il barbiere di Seviglia - in 1975; his New York operatic début came with Puccini's La fanciulla del West two years later. Music directorship of the New York City Opera followed in 1987-88, and in 1989 he appeared at the Metropolitan Opera with Mozart's Don Giovanni. Further afield, he was the chief conductor of the Radio Philharmonic Orchestra in Hilversum from 1982 and of the Helsinki Philharmonic for three years from 1990 - a position he held simultaneously with the Radio- Televisión Orquestra Sinfónica in Madrid and, from 1991, with the Vancouver Symphony Orchestra, where he remained until 2000 and was described as "the best thing to happen to Vancouver's musical life in a generation". At the time of his death on March 5, 2005 - in his sleep but also in the saddle: he was in Oklahoma City to give a concert - Comissiona held a number of posts, among them the principal guest conductorships of the Jerusalem Symphony, the George Enescu Philharmonic (Bucharest) and the University of Southern California Symphony Orchestras. Stephen Cera sums up Comissiona as, "a tremendously gifted "born" conductor with a decidedly unorthodox technique that could not have been easy to follow. In many ways he was old-fashioned in the best sense - almost a throwback to an earlier era of conducting giants . . . His acute ear for subtly nuanced orchestral sound distinguished his finest performances: an almost alchemical ability to transform the dry ink of musical notation into bewitching sound-images." Comissiona's repertoire was huge and is reflected in his substantial discography, which is distinguished by an adventurous taste in repertoire: he was recording little-known composers like the Swedish symphonist Allan Pettersson long before this marginal post-Mahlerian became fashionable. -- Martin Anderson, The Independent, March 11, 2005

|

Sergiu Comissiona: I enjoy doing any kind of orchestra

because I like to work, even when it is an orchestra that is in transition.

I must confess to you — but only to you, of course!

— that I make a very bad guest conductor. I don’t go through

the music and say, “Bravo, wonderful,”

and keep smiling. After the five minutes I will say, “Okay,

now let’s start to work!” I keep the orchestra

working until the last second, until the exasperated personnel managers make

the sign indicating I have five seconds to finish! So in this respect,

I label myself a bad guest conductor. I love to work, and it’s a challenge,

but being a guest your work is limited.

Sergiu Comissiona: I enjoy doing any kind of orchestra

because I like to work, even when it is an orchestra that is in transition.

I must confess to you — but only to you, of course!

— that I make a very bad guest conductor. I don’t go through

the music and say, “Bravo, wonderful,”

and keep smiling. After the five minutes I will say, “Okay,

now let’s start to work!” I keep the orchestra

working until the last second, until the exasperated personnel managers make

the sign indicating I have five seconds to finish! So in this respect,

I label myself a bad guest conductor. I love to work, and it’s a challenge,

but being a guest your work is limited.

SC: This is a question that depends on which orchestra

I am with. If it is my orchestra where I am Music Director, I’m planning

a five-year diet for the orchestra, for myself, for the public, and without

using the term ‘education’, we are working on developing a taste for music.

I consult to what was played in ten, fifteen, twenty years ago to see what

was missing and in which direction I should go. Also, without having

too much new music so as not to be scary, but to spoon in some new novelties.

When I say novelties, it doesn’t mean the most avant-garde, but music which

the public and also the orchestra don’t really know. I hope I’ve proved

in my seventeen years as Musical Director in Baltimore that the public will

trust me. So even if they don’t know this work, if Comissiona asks,

it must be something important. With every orchestra which I work, the

quality of the Music Director can get this trust to schedule works.

Sometime there is a shock, but I don’t want to lose this effort when economics

are so important. A music director is judged not only by his artistic

or musical successes but also by statistics at the box office, by numbers

of subscribers. So we are leading an orchestra not only with some good

critics, but with mathematics. I want them to say, “He

came and they had only 3,000 subscribers and he left with 8,000 subscribers!”

Then you’ve not only been a good conductor, but also a good Music Director.

This is the difference, and we have to also be good administrators.

As guest conductor you suggest a number of programs, and then the Music Director

decides what would be good for their orchestra. Having a large repertoire,

I’m not insisting anymore that I want to do Brahms Second Symphony. Whatever they would

prefer for their orchestra, I more or less gladly will accept. If it

is something which is completely outside of my scope, then of course I say

that I am sorry.

SC: This is a question that depends on which orchestra

I am with. If it is my orchestra where I am Music Director, I’m planning

a five-year diet for the orchestra, for myself, for the public, and without

using the term ‘education’, we are working on developing a taste for music.

I consult to what was played in ten, fifteen, twenty years ago to see what

was missing and in which direction I should go. Also, without having

too much new music so as not to be scary, but to spoon in some new novelties.

When I say novelties, it doesn’t mean the most avant-garde, but music which

the public and also the orchestra don’t really know. I hope I’ve proved

in my seventeen years as Musical Director in Baltimore that the public will

trust me. So even if they don’t know this work, if Comissiona asks,

it must be something important. With every orchestra which I work, the

quality of the Music Director can get this trust to schedule works.

Sometime there is a shock, but I don’t want to lose this effort when economics

are so important. A music director is judged not only by his artistic

or musical successes but also by statistics at the box office, by numbers

of subscribers. So we are leading an orchestra not only with some good

critics, but with mathematics. I want them to say, “He

came and they had only 3,000 subscribers and he left with 8,000 subscribers!”

Then you’ve not only been a good conductor, but also a good Music Director.

This is the difference, and we have to also be good administrators.

As guest conductor you suggest a number of programs, and then the Music Director

decides what would be good for their orchestra. Having a large repertoire,

I’m not insisting anymore that I want to do Brahms Second Symphony. Whatever they would

prefer for their orchestra, I more or less gladly will accept. If it

is something which is completely outside of my scope, then of course I say

that I am sorry. BD: So then you don’t really have much choice?

BD: So then you don’t really have much choice? SC: Maybe not, to be sincere, but they are more

committed due to the fact that every chair is so important. They know

they’re not engaged just to sit on a chair. I find more and more that

even not only the great orchestras are committed. They are interested

to play, and this is the joy for everyone. You can feel it in the hall

when they are not just playing down and up and 1, 2, 3, 4. You can feel

that everyone is trying. Every day in the rehearsal, day by day, the

musician is improving now. I am very happy that I meet sometimes musicians

I knew maybe ten years ago, and they are so developed, certainly not only

technically but musically. But again it’s a matter of being individual.

You will always be finding people who are interested, and others who say,

“I’m playing my notes. What more do you want?”

[Both laugh]

SC: Maybe not, to be sincere, but they are more

committed due to the fact that every chair is so important. They know

they’re not engaged just to sit on a chair. I find more and more that

even not only the great orchestras are committed. They are interested

to play, and this is the joy for everyone. You can feel it in the hall

when they are not just playing down and up and 1, 2, 3, 4. You can feel

that everyone is trying. Every day in the rehearsal, day by day, the

musician is improving now. I am very happy that I meet sometimes musicians

I knew maybe ten years ago, and they are so developed, certainly not only

technically but musically. But again it’s a matter of being individual.

You will always be finding people who are interested, and others who say,

“I’m playing my notes. What more do you want?”

[Both laugh] SC: Yes. I did it already before. Because

during the concert you cannot read at the last minute, but to have it already

in this half an hour drive, you can already start to get into the mood of

the concert. That’s not a discipline. I’m also asking the musicians

to come before, especially to concentrate, to be simply with the public.

In Japan, I was very impressed last year when I conducted in a new hall, the

Art Space Center in Tokyo. Most of the public were seated half an hour

before, and the stage, instead of an acoustical shell of wood, it was glass

and a Japanese garden. The people were very quiet, looking at this

garden. Then five minutes before the concert started, they close this

glass so they could not see the garden anymore. The people have this

kind of concentration even before the music starts.

SC: Yes. I did it already before. Because

during the concert you cannot read at the last minute, but to have it already

in this half an hour drive, you can already start to get into the mood of

the concert. That’s not a discipline. I’m also asking the musicians

to come before, especially to concentrate, to be simply with the public.

In Japan, I was very impressed last year when I conducted in a new hall, the

Art Space Center in Tokyo. Most of the public were seated half an hour

before, and the stage, instead of an acoustical shell of wood, it was glass

and a Japanese garden. The people were very quiet, looking at this

garden. Then five minutes before the concert started, they close this

glass so they could not see the garden anymore. The people have this

kind of concentration even before the music starts.

This conversation was recorded at the Pfister Hotel in Milwaukee, Wisconsin on December 29, 1995. Portions were broadcast on WNIB in 1998, and on WNUR in 2002 and 2005. This transcription was made in 2014, and posted on this website at that time. My thanks to British soprano Una Barry for her help in preparing this website presentation.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website, click here. To read my thoughts on editing these interviews for print, as well as a few other interesting observations, click here.

Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM, as well as on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio.

You are invited to visit his website for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.