Tobias Picker (b. New York City, July 18, 1954),

called “our finest composer for the lyric stage” by The Wall Street Journal,

is a composer of numerous works in every genre drawing performances by

the world’s leading musicians, orchestras and opera houses. Picker began

composing at the age of eight and studied at the Manhattan School of Music,

The Juilliard School and Princeton University where his principal teachers

were Charles Wuorinen,

Elliott Carter

and Milton Babbitt.

His first commissions occurred while still in his late teens and he quickly

became established as one of America’s most sought-after young composers.

By the age of thirty, Picker was the recipient of numerous

awards and honors including the Bearns Prize (Columbia University), a Charles

Ives Scholarship, and a Guggenheim Foundation Fellowship. He received the

prestigious Award in Music from the American Academy of Arts and Letters

in 1992 and was elected to lifetime membership in the Academy in 2012.

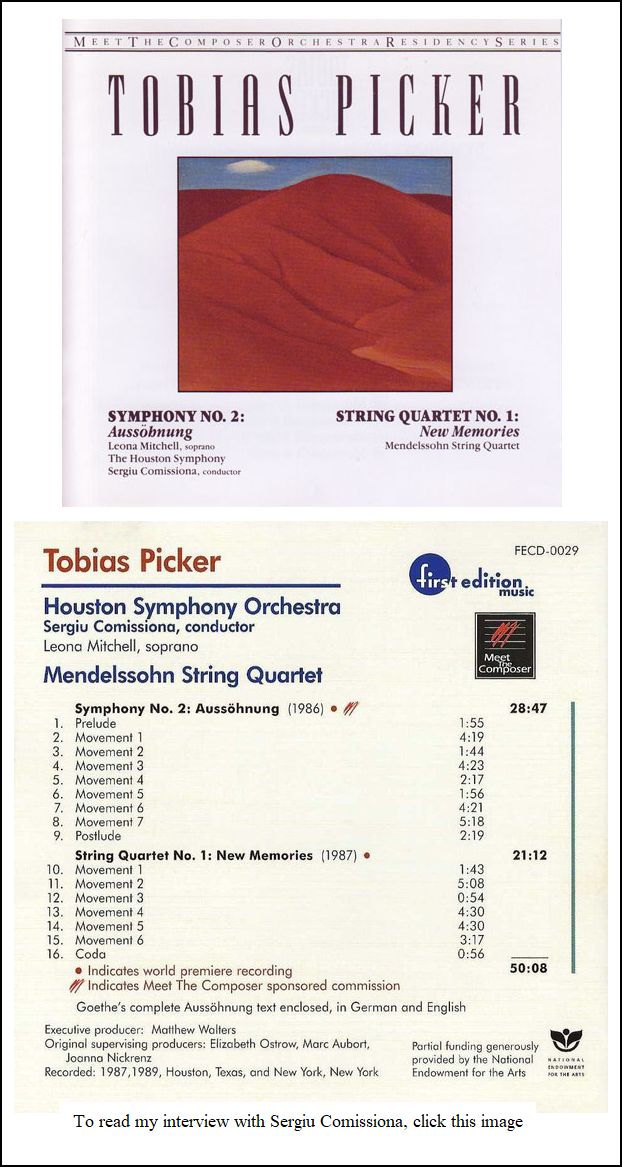

Picker served as the first composer-in-residence of the Houston Symphony

from 1985-90, and has served as composer-in-residence for such major international

festivals as the Santa Fe Chamber Music Festival and the Pacific Music Festival.

From 2010-2015, Picker served as Artistic Director of Opera San Antonio.

In 2016, Picker was appointed Artistic Director of Tulsa Opera.

By the age of thirty, Picker was the recipient of numerous

awards and honors including the Bearns Prize (Columbia University), a Charles

Ives Scholarship, and a Guggenheim Foundation Fellowship. He received the

prestigious Award in Music from the American Academy of Arts and Letters

in 1992 and was elected to lifetime membership in the Academy in 2012.

Picker served as the first composer-in-residence of the Houston Symphony

from 1985-90, and has served as composer-in-residence for such major international

festivals as the Santa Fe Chamber Music Festival and the Pacific Music Festival.

From 2010-2015, Picker served as Artistic Director of Opera San Antonio.

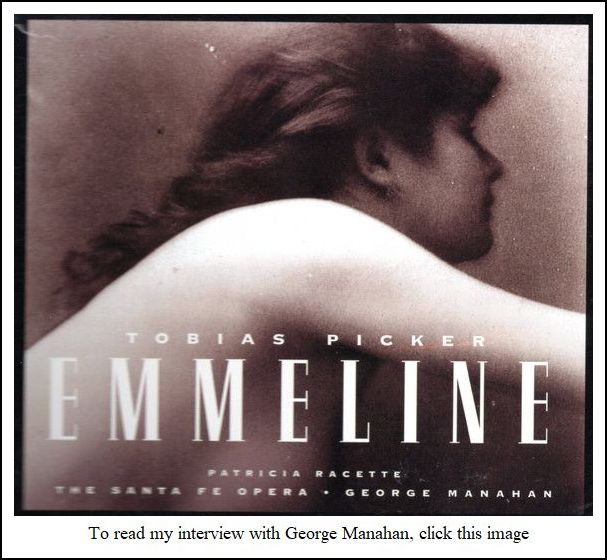

In 2016, Picker was appointed Artistic Director of Tulsa Opera.The Santa Fe Opera gave the world premiere of Picker’s internationally acclaimed first opera Emmeline in 1996. [CD cover shown at left] It was subsequently broadcast nationally on the PBS “Great Performances” series. The opera played to sold-out houses and international critical acclaim, and the opera’s premiere at New York City Opera was hailed by The New York Times as one of the ten most significant musical events of 1998. Opera Theatre of St. Louis mounted a major new production in June 2015, which garnered universal acclaim as “one of the best operas written in the past 25 years (The Wall Street Journal). Picker’s second opera, based on Roald Dahl’s Fantastic Mr. Fox and commissioned and premiered by the Los Angeles Opera in a production starring Gerald Finley, established Picker as a composer whose appeal crosses all boundaries of age. Fantastic Mr. Fox recently completed a sold-out, three-year run at London’s Opera Holland Park, and the English Touring Opera toured the work extensively in England, Wales, Ireland and Scotland. OPERA San Antonio presented a new production of Fantastic Mr. Fox, created especially for the inaugural season of the Tobin Center, in September 2014. The Boston Modern Orchestra Project released the premiere recording of Fantastic Mr. Fox in its original orchestration and featuring Opera San Antonio’s acclaimed cast. A consortium of The Dallas Opera, San Diego Opera, and Opéra de Montréal commissioned Picker’s third opera, Thérèse Raquin, which was staged by Francesca Zambello. A reduced version of Thérèse Raquin was commissioned by Opera Theatre Europe and given its London premiere at Covent Garden ROH2. The reduced version has since received productions with Dicapo Opera Theatre, Long Beach Opera, Chicago Opera Theater, Boston University Opera Institute, and Microscopic Opera. The Metropolitan Opera commissioned Picker’s fourth opera, An American Tragedy, based on the novel by Theodore Dreiser (which also inspired the film A Place in the Sun). The world premiere of the opera took place at the Met in December 2005, featuring Patricia Racette, Nathan Gunn, Susan Graham, and Dolora Zajick in principal roles. The production was directed by Francesca Zambello and conducted by James Conlon. The Glimmerglass Festival gave the premiere of the revised version of An American Tragedy to wide acclaim in 2014. Picker’s fifth opera, Dolores Claiborne, based on the Stephen King novel, starred Patricia Racette and Elizabeth Futral at its world premiere presented by San Francisco Opera in September 2013. Dolores Claiborne was hailed as “a triumph” (Opera News), “the best of his five operas” (The Los Angeles Times), “a brilliant musical incarnation” (The Huffington Post) and “an unflinching addition to the repertoire” (San Francisco Chronicle).

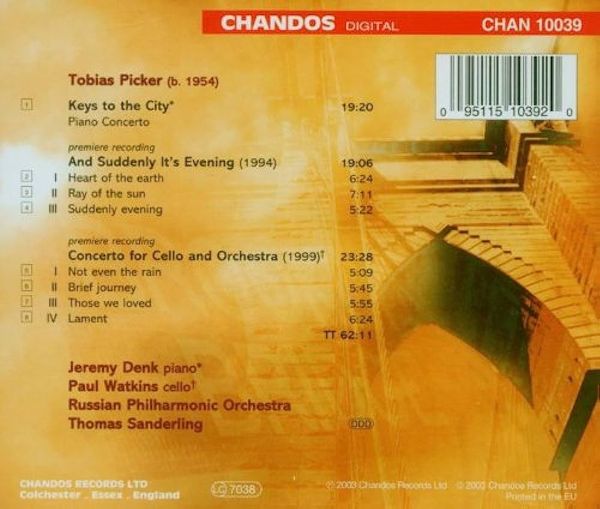

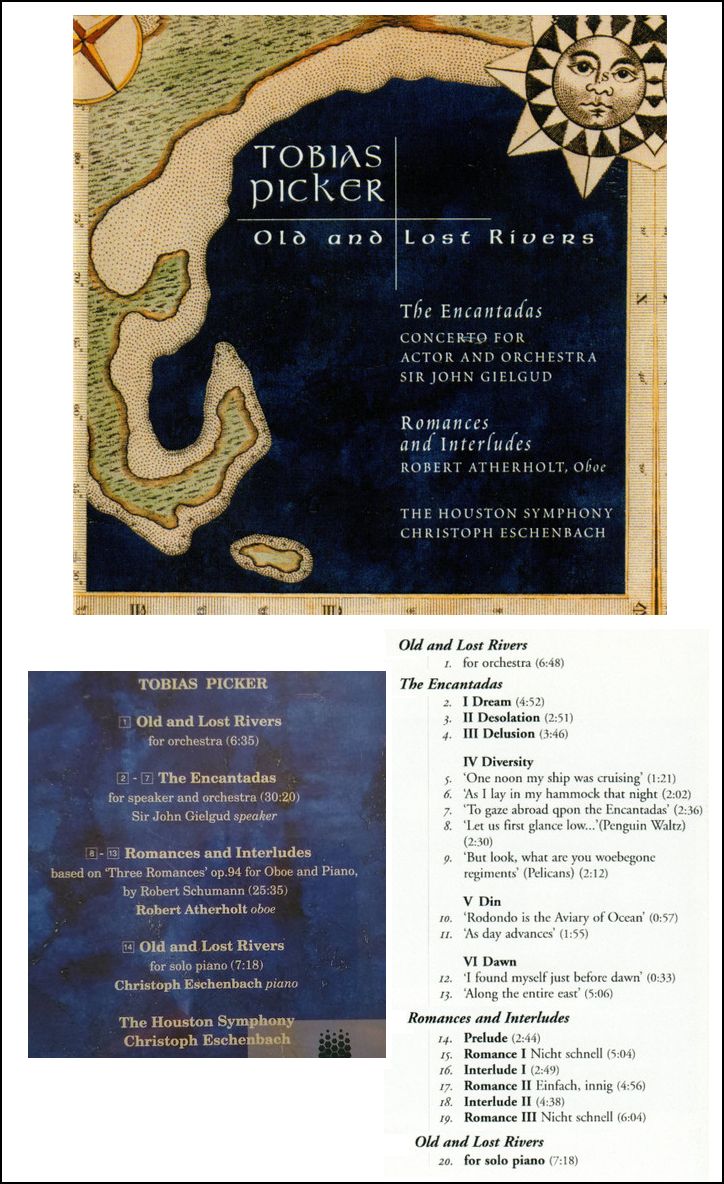

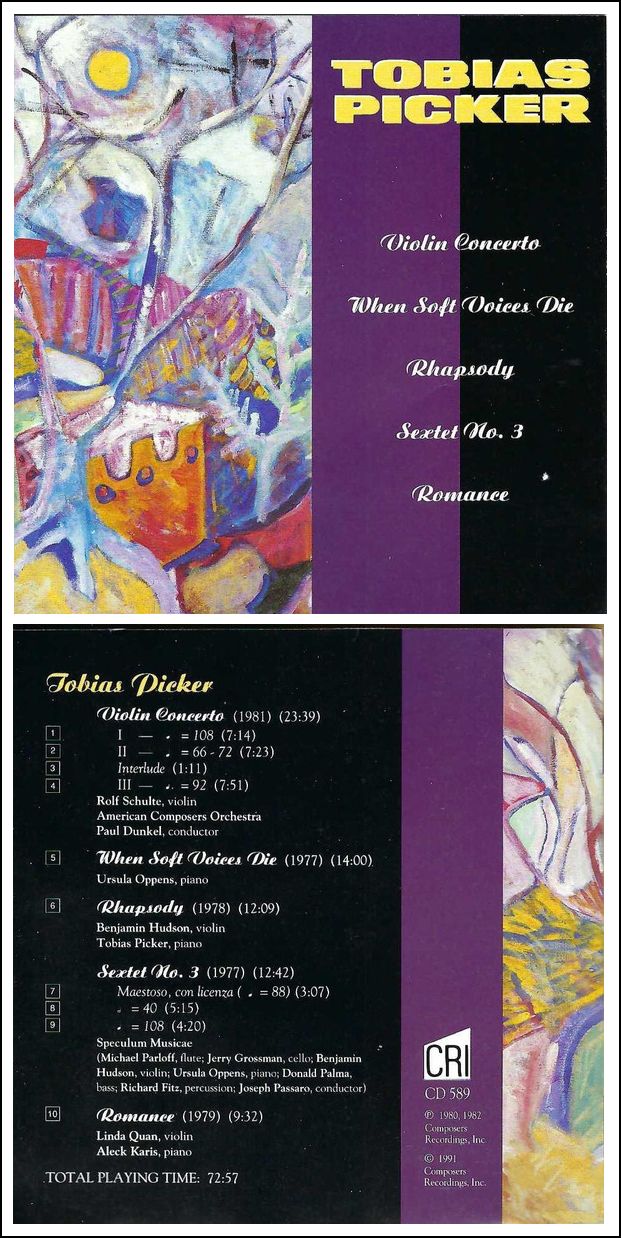

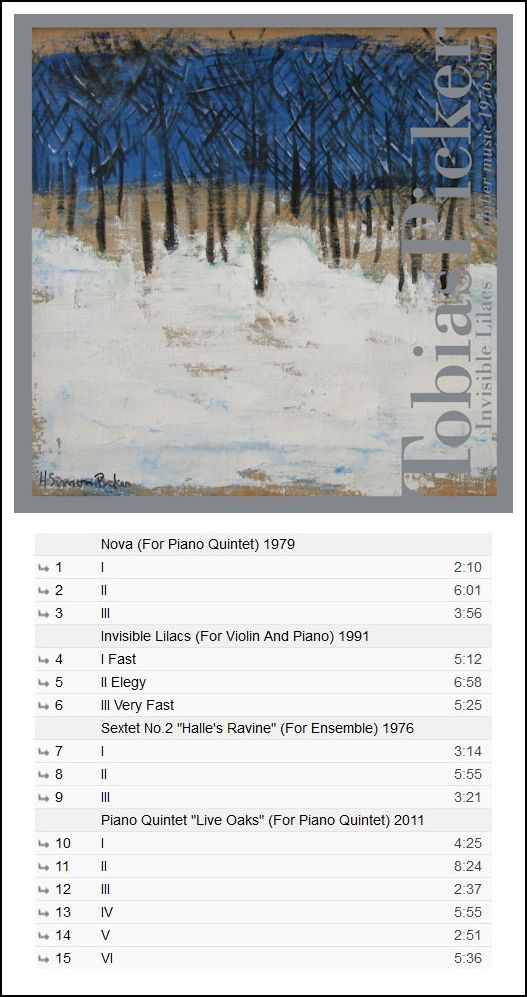

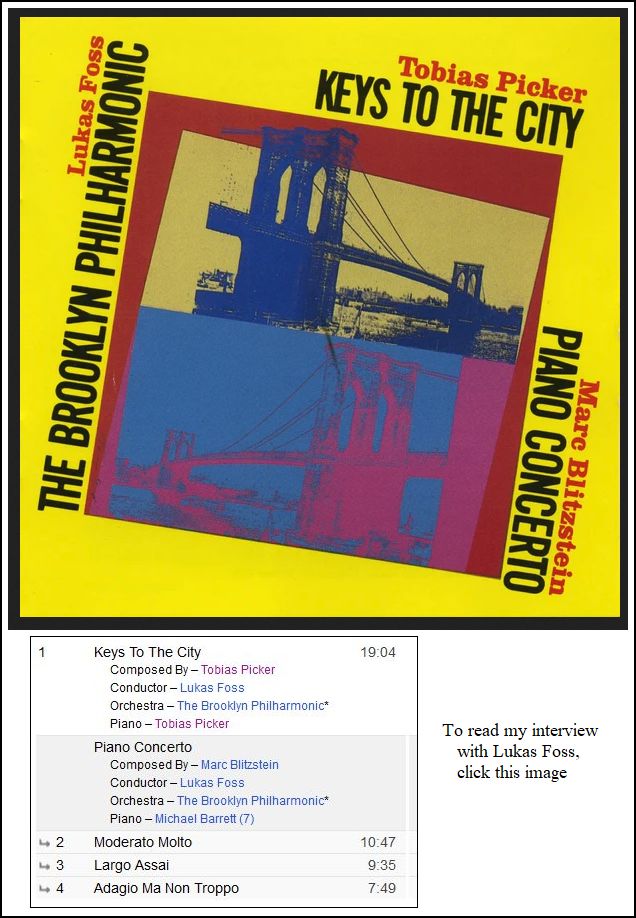

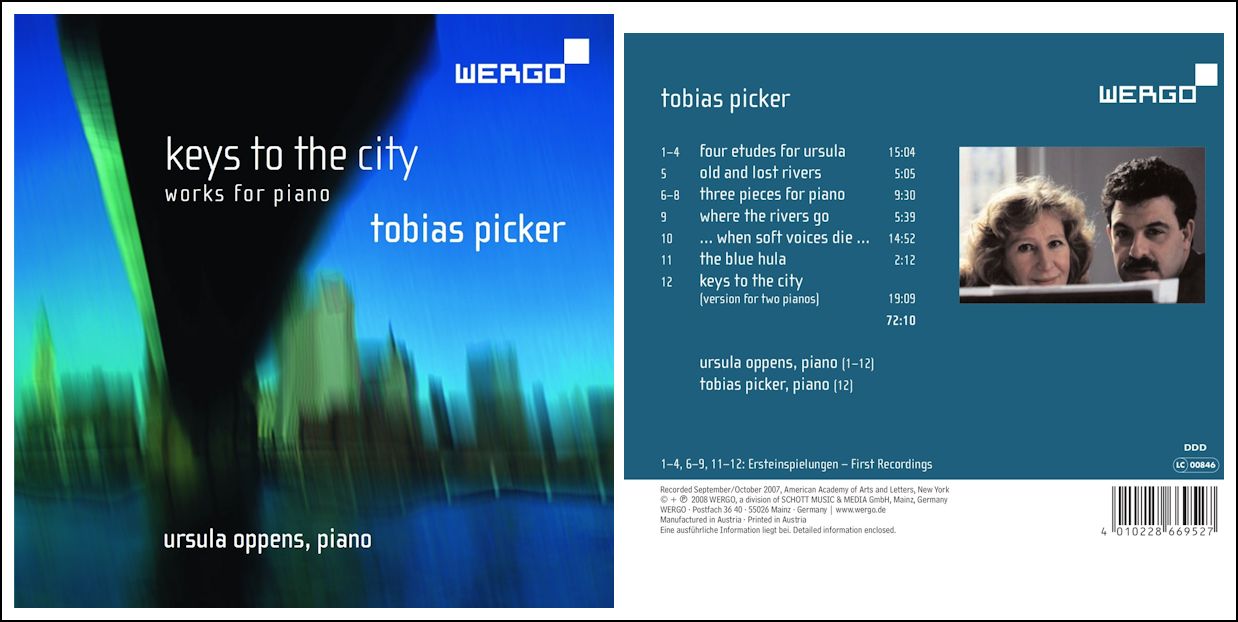

Picker’s symphonic music, including his famous tone poem Old and Lost Rivers, composed while he was composer-in-residence at the Houston Symphony, has been commissioned and performed by major orchestras around the world such as the BBC Philharmonic, Chicago Symphony, Cleveland Orchestra, Helsinki Philharmonic, L’Orchestre de Paris, Munich Philharmonic, New York Philharmonic, Philadelphia Orchestra, San Francisco Symphony, Vienna RSO, and Zurich Tonhalle. His second piano concerto, Keys to the City (commissioned by the City of New York on the occasion of the centenary of the Brooklyn Bridge) is a perennial favorite, called “a vivid musical portrait of New York” by The New York Times and recorded by Jeremy Denk on Chandos [CD back-insert shown at right], along with his Cello Concerto and the orchestral work And Suddenly It’s Evening. The Encantadas (for actor and orchestra) features texts drawn from Herman Melville’s poetic descriptions of the Galapagos Islands and was recorded by the Houston Symphony with Sir John Gielgud; it has been performed throughout the world in seven languages. In addition to his five operas, Picker’s catalogue includes four symphonies, four piano concertos, concertos for violin, viola, cello and oboe, song cycles, string quartets, and chamber music. His ballet Awakenings, based on the themes and case studies in the novel of the same name by neurologist Dr. Oliver Sacks, was commissioned by the Rambert Dance Company, which toured the work throughout the UK in 2011, performing it 80 times. His extensive discography has been recorded on such labels as Nonesuch, Sony Classics, Virgin Classics, Chandos, Ondine, and Albany Records. Most recently, Wergo and Tzadik have devoted complete albums to Picker’s chamber music spanning the years 1976 to 2011, including the album Invisible Lilacs released by Tzadik in March 2014. Picker’s first four operas received new productions in the 2014-2015 season at The Glimmerglass Festival (An American Tragedy), Opera San Antonio (Fantastic Mr. Fox), Opera Theatre of St. Louis (Emmeline), Chicago Opera Theater and Long Beach Opera (Thérèse Raquin). Called “seductive yet enigmatic” by The Washington Post, Picker’s large-scale orchestral work Opera Without Words received its world premiere with the National Symphony Orchestra in 2016, conducted by Christoph Eschenbach. In 2017, the New York City opera premiered the chamber version of Dolores Claiborne, and the National Symphony Orchestra celebrated the thirtieth anniversary of Old and Lost Rivers with performances of the work at the Kennedy Center and on tour in Moscow and St. Petersburg at the Mstislav Rostropovich Festival. In 2018, Picker led the Signature Symphony in a performance of arias from his operas, including "The Ghost Aria" and "The Seine Moves Like a Melody" from Thérèse Raquin and "The Letter Aria" and "Love Duet" from Emmeline. which have subsequently been made available as stand-alone concert works for voice(s) and orchestra. Tobias Picker’s music is published exclusively worldwide by Schott Helicon Music Corporation. == Biography from the website of Schott Music

== Names which are links in this box and below refer to my interviews elsewhere on my website. BD |

© 1994 Bruce Duffie

This conversation was recorded in in Chicago on March 9, 1994. Portions were broadcast on WNIB four months later, and again in 1999. This transcription was made in 2023, and posted on this website at that time.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website, click here. To read my thoughts on editing these interviews for print, as well as a few other interesting observations, click here.

Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM, as well as on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio.

You are invited to visit his website for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.