|

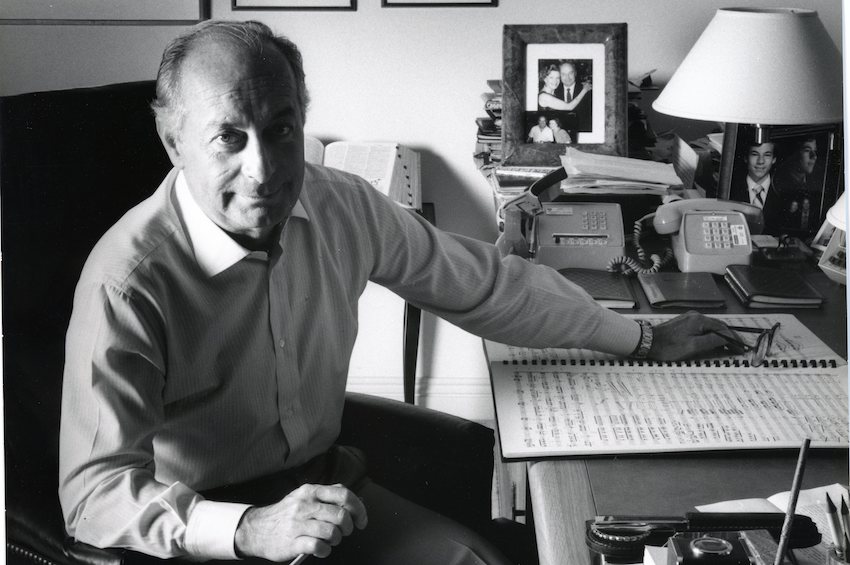

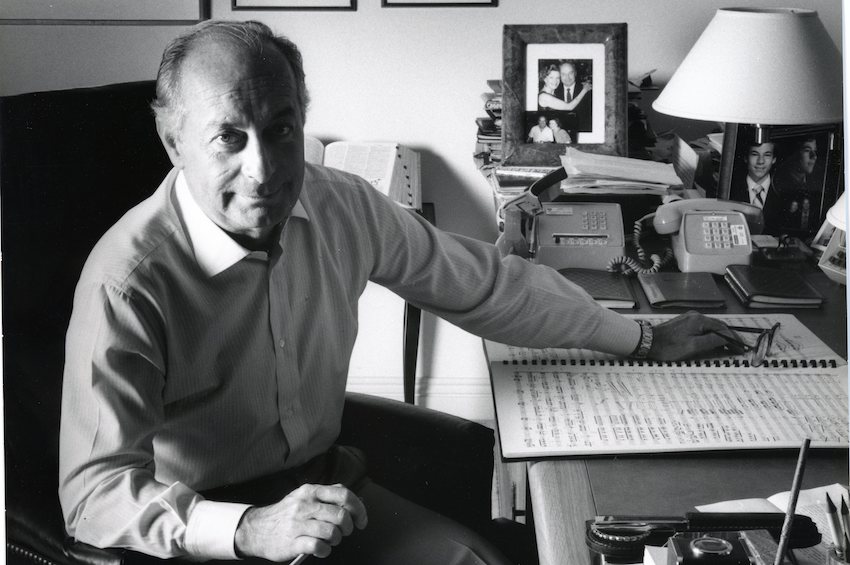

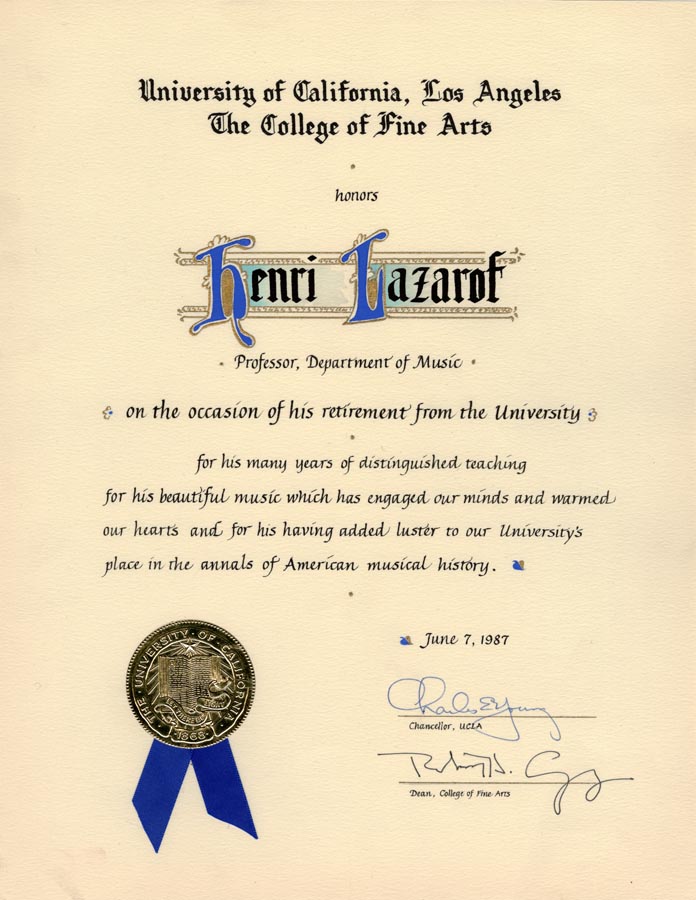

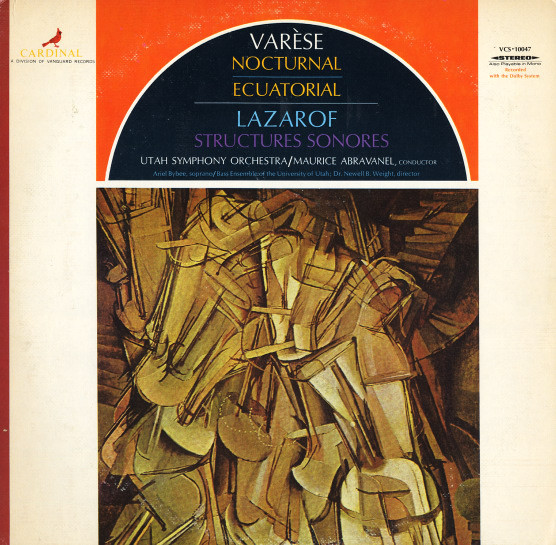

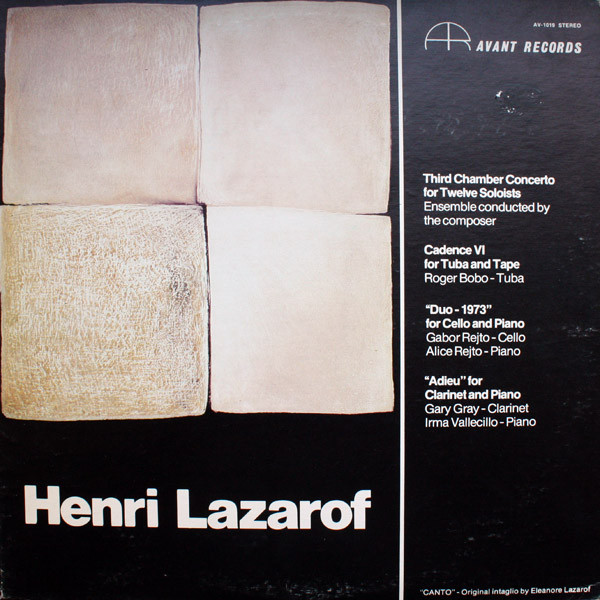

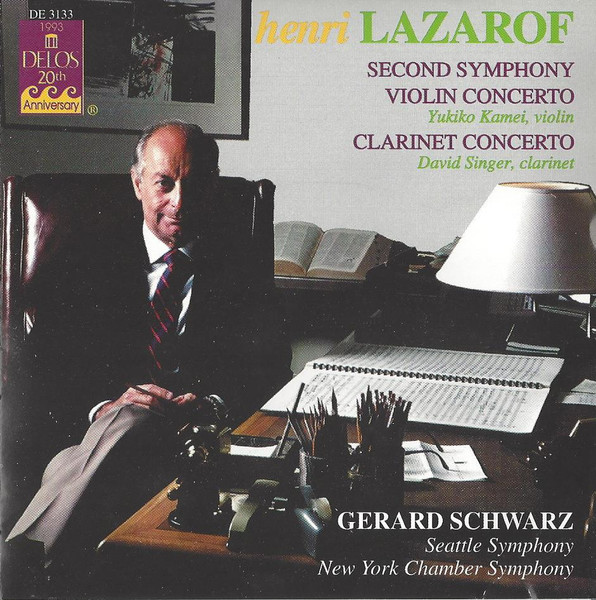

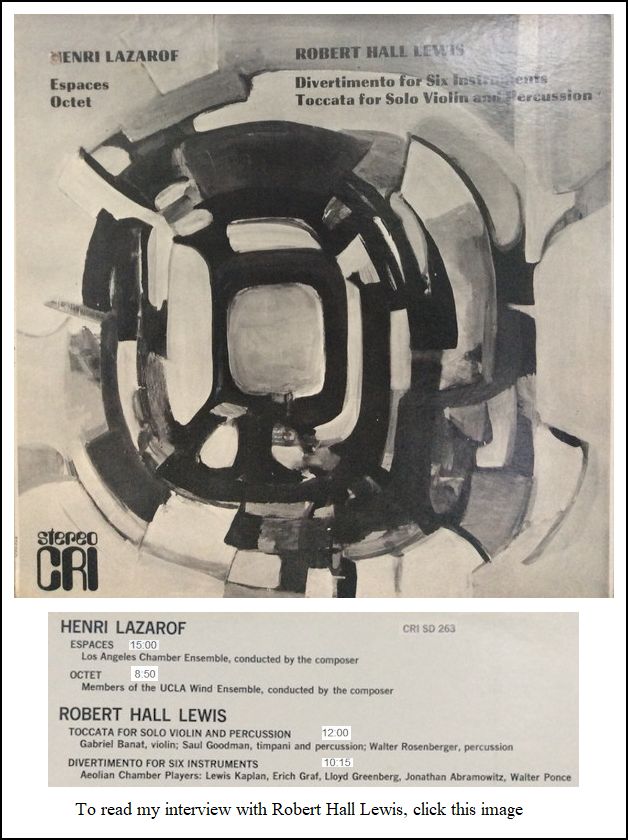

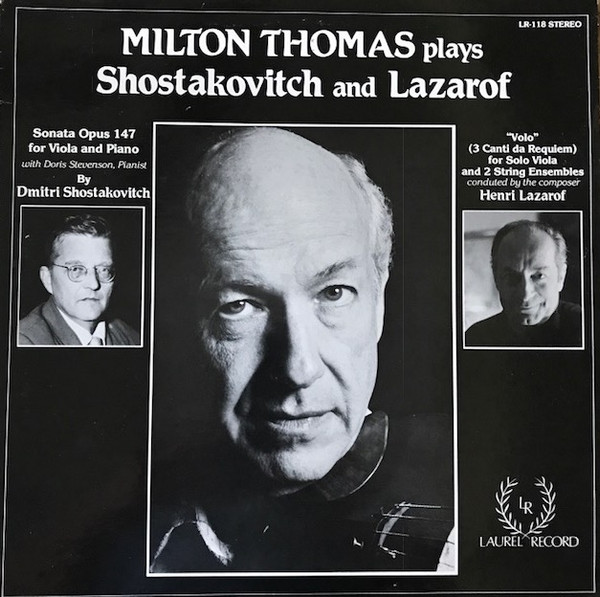

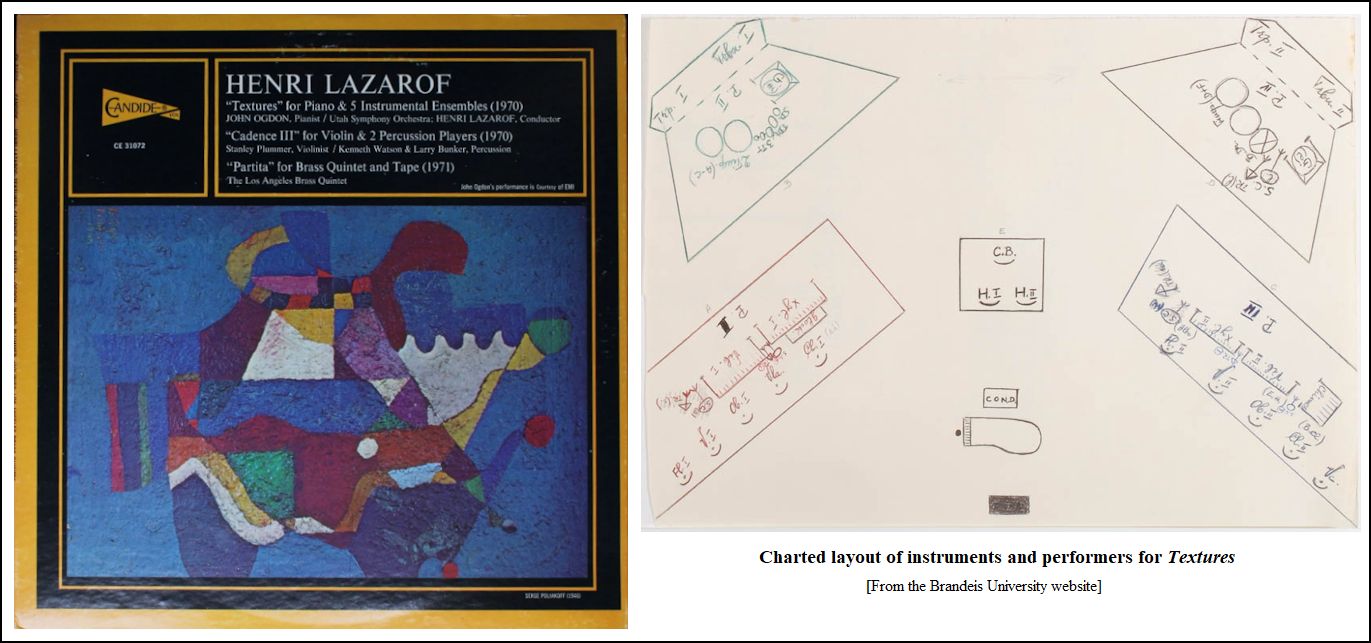

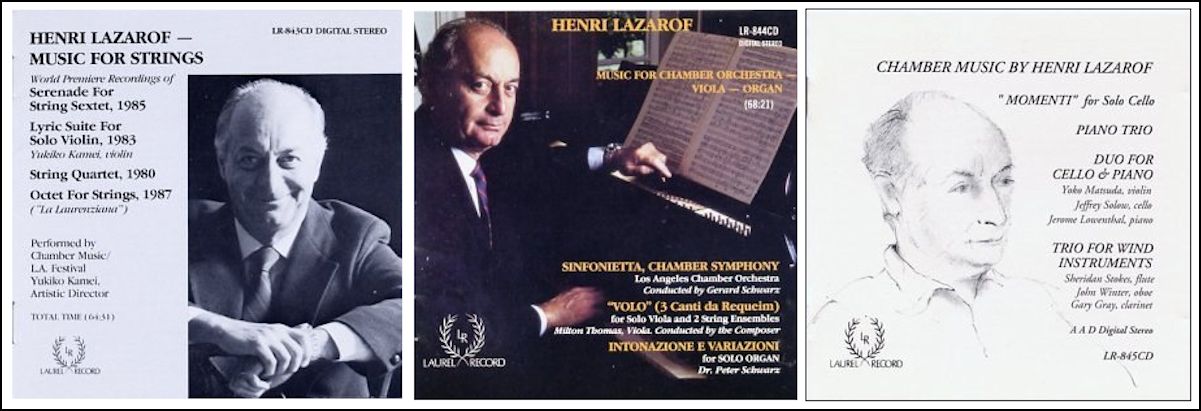

Henri Lazarof was born in Sofia, Bulgaria April 2, 1932. His first music lessons were with the Jesuit Lycee Francais. By his teenage years he was already a concert pianist and was beginning to study musical composition. After World War II, he left Bulgaria with his family to emigrate to Palestine (1946), and studied composition with Paul Ben-Haim in Jerusalem (1949-1952). While in the Israeli Army, he organized concerts for the Israeli troops throughout Israel. He won the first musical scholarship awarded in Israel to attend the Accademia di Santa Cecilia in Rome, where he was a student of Goffredo Petrassi (1955–1957). He completed his studies with Arthur Berger and Harold Shapero on a fellowship at Brandeis University in 1959. That same year he became a naturalized U.S. citizen and relocated to Southern California where he became a teacher of French language and literature at the University of California, Los Angeles. Early CareerIn 1962, Lazarof joined the music faculty of UCLA, teaching composition and organizing contemporary music festivals, and remained at UCLA until his retirement (1987), excepting the 1970-71 term, when he was artist-in-residence in West Berlin and 1979, when he became artist-in-residence at Tanglewood Music Center in Boston. By 1982, Lazarof was devoting nearly full-time to musical composition. During his lifetime, Henri Lazarof had 126 musical works published with Associated Music Publishers (G. Schirmer, Inc.), Theodore Presser Company, and Bote and Bock et. al. Additionally, many of his compositions were recorded by multiple classical record labels. Fluent in nine languages, Mr. Lazarof died December 29, 2013. CompositionsA partial list of Lazarof works includes seven symphonies, three concertos for orchestra, three violin concertos, three cello concertos, two flute concertos, a viola concerto, a piano concerto, 11 string quartets, and innumerable pieces for orchestra, chamber orchestra, small ensembles, solo instruments, and mixed chorus. Numerous works were commissioned and recorded, and premiered by various orchestras throughout Europe, Asia, and the United States, including Carnegie Hall in New York; "First Symphony" with the Utah Symphony Orchestra; "Concerto No. 2 Icarus" with the Houston Symphony Orchestra; "Concerto for Oboe and Chamber Orchestra" with the New York Chamber Symphony; and “Flute Concerto” with James Galway and the Berlin Symphony Orchestra. Mr. Lazarof's passion for visual art was reflected in his music—such as his "String Quartet No. 8," a homage to Paul Klee, and "Tableaux (after Kandinsky)" premiered by Garrick Ohlson and the Seattle Symphony Orchestra. AwardsLazarof's prizes included first place in the International Tchaikovsky Competition; First International Competition from Monaco for Concerto for Viola and Orchestra; and First International Prize City of Milan La Scala Award for his musical composition, "Structures Sonores." He also received grants from the Ford Foundation and the National Endowment for the Arts, as well as two Grammy nominations in 1991 for Best Contemporary Composition and Best Classical Performance - Instrumental Soloist(s) with Orchestra.

== Text of biography above is from the Brandeis

University website

== Material below is from other sources == Names which are links in this box and below refer to my interviews elsewhere on my website. BD In December 2007, Janice and Henri Lazarof gave the Los Angeles County Museum of Art 130 mostly Modernist works estimated to be worth more than $100 million. The collection includes 20 works by Picasso, watercolors and paintings by Paul Klee and Wassily Kandinsky and a considerable number of sculptures by Alberto Giacometti, Constantin Brâncuși, Henry Moore, Willem de Kooning, Joan Miró, Louise Nevelson, Archipenko and Arp. |

|

Herschel Burke Gilbert (April 20, 1918 - June 8, 2003) was born in Milwaukee, Wisconsin, began violin lessons at age nine, in Shorewood, Wisconsin, where he was concertmaster of the award-winning high school orchestra and drum major for the band · He began his own dance band at age 15, performing at high schools and colleges throughout the state of Wisconsin

1939-1941: two years Juilliard Institute of Musical Art (violin and viola) 1941-1943: two Years Juilliard Graduate school, with two consecutive yearly fellowships in conducting with Albert Stoessel · Herschel studied composition with Bernard Waganaar and Vitorio Gianinni, and played first viola in the Juilliard Graduate School Orchestra 1942: Viola scholarship at Berkshire Music Festival, Tanglewood, Massachusetts, performing under Serge Koussevitsky · Here also, Gilbert studied composition with Aaron Copland, Leonard Bernstein, and Lukas Foss 1946: Studied advanced composition privately with Ernst Toch - who also taught at the University of California at Los Angeles (UCLA) 1943: Left Juilliard to accept positions as music arranger and violist with the Harry James Orchestra, traveling to Hollywood to work in films 1945: Obtained arranging and orchestration assignments from Columbia Pictures · Arranged and orchestrated for film composers Dimitri Tiomkin, Werner Heyman, and Heinz Roemheld From 1947: Composer-conductor, arranger-orchestrator of over sixty feature motion pictures for Columbia Pictures, United Artists, and 20th Century Fox (independent producers), winning three Academy Award Nominations 1958-1964: Executive Music Director of Dick Powell's Four Star Television Company · Music composer and supervisor of 1500 television episodes (winning three Emmy nominations) Vice President, Four Star TV Music Publishing Company (BMI) and BNP Music (ASCAP) 1965-1966: Executive Music Director of the CBS Television Network · Composer, conductor and music supervisor of 300 CBS television episodes · Composer-conductor of Rawhide's two hour episode, Damon's Road, for which he received the Cowboy Hall of Fame Award in Oklahoma City, presented by John Wayne 1974: Founded Consortium Recordings, a non-profit company, to record, produce and distribute classical chamber music recordings · Also formed GSC Recordings, solely to record the chamber music of Paul Hindemith; and started Laurel Record, Gilbert's personal record label, to produce and release classical chamber music== Biography from the Laurel Record website

|

© 1992 Bruce Duffie

This conversation was on the telephone on April 6, 1992. Portions were broadcast on WNIB in 1997 for his 65th birthday. This transcription was made in 2022, and posted on this website at that time. My thanks to British soprano Una Barry for her help in preparing this website presentation.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website, click here. To read my thoughts on editing these interviews for print, as well as a few other interesting observations, click here.

Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM, as well as on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio.

You are invited to visit his website for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.