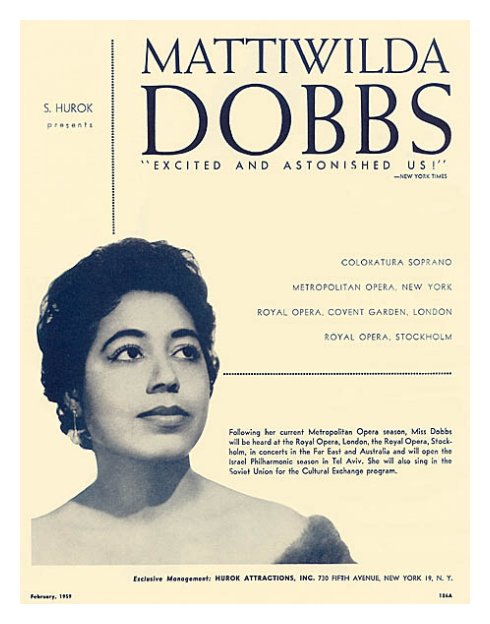

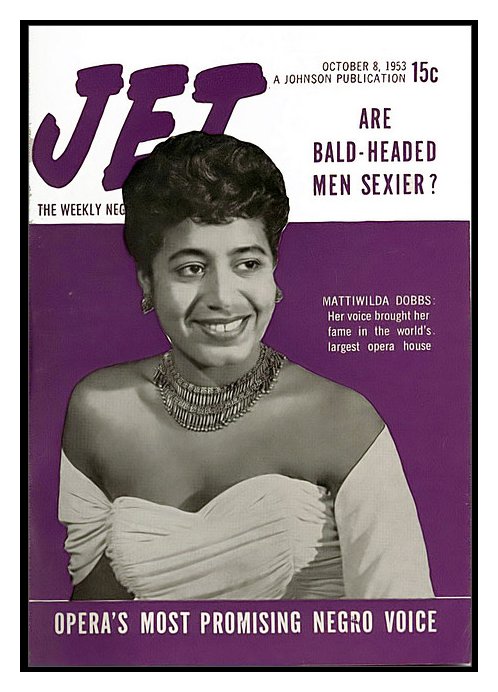

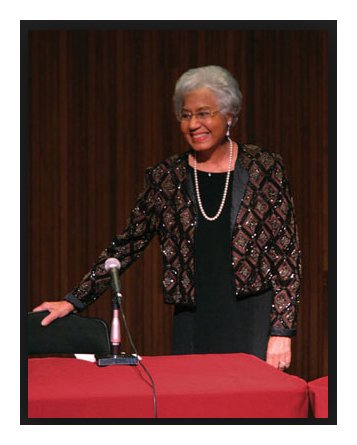

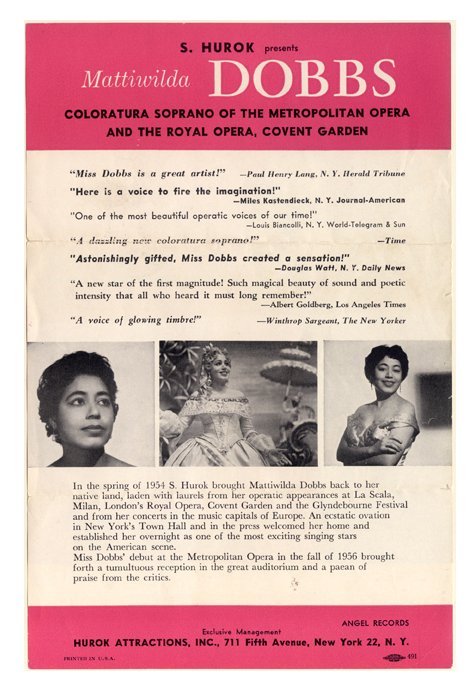

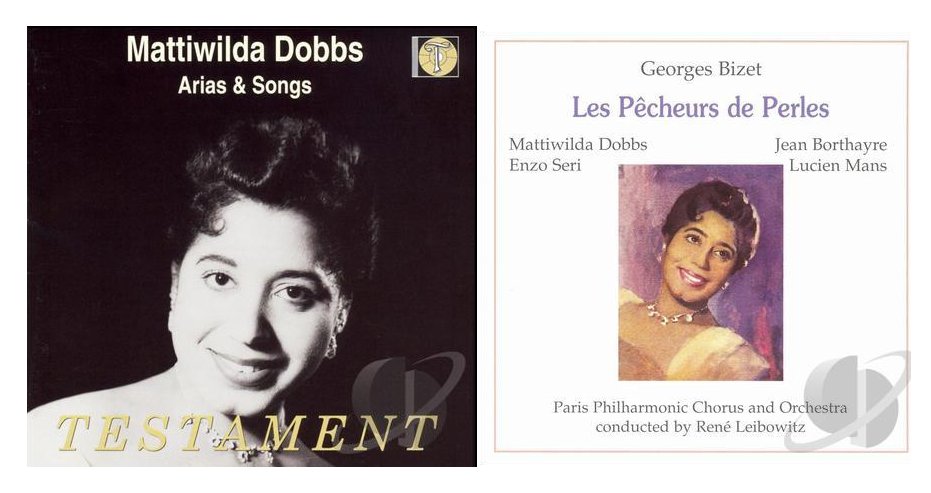

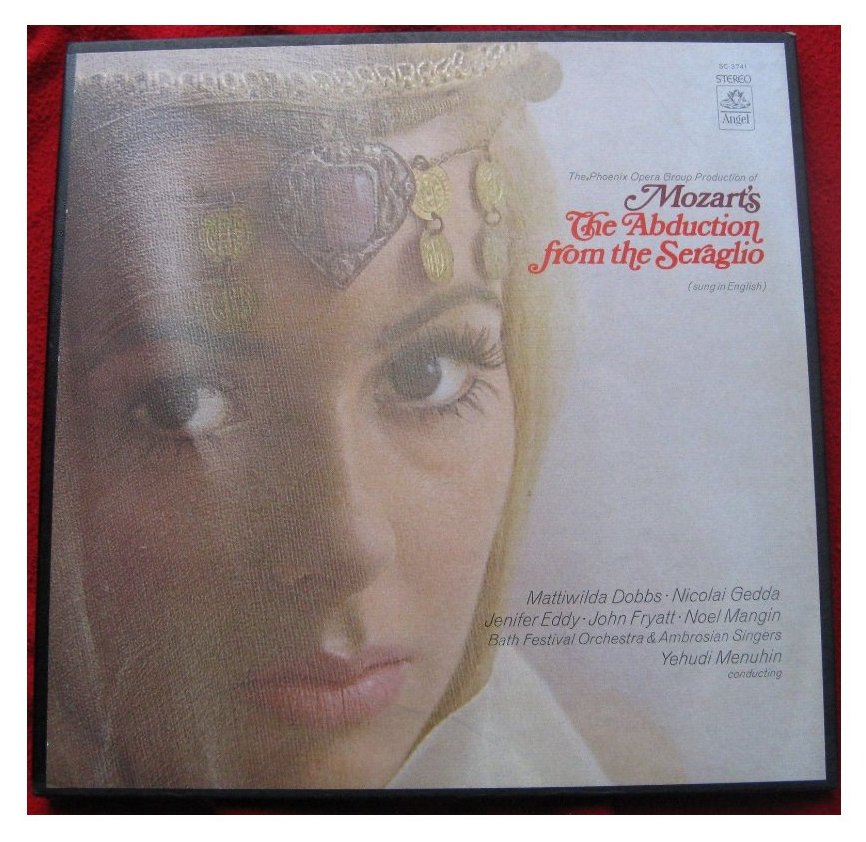

Mattiwilda Dobbs's exceptional vocal

gifts and musical skill enabled her to cross color barriers to become an internationally

known opera star. The Atlanta native was the first African American to sing

at La Scala in Milan, Italy, and the first black woman to be offered a long-term

contract by the Metropolitan Opera Company in New York.

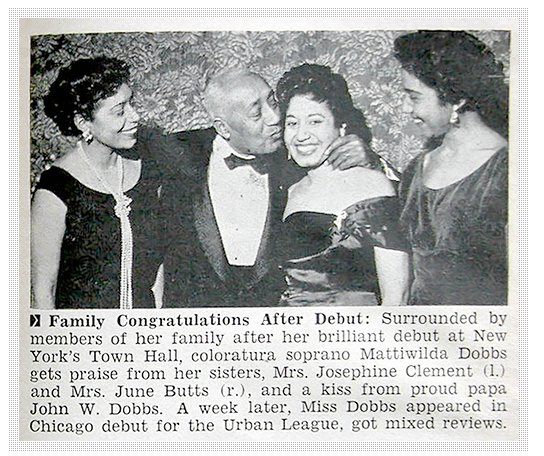

Named for her maternal grandmother, Mattie Wilda Sykes, Mattiwilda Dobbs was born on July 11, 1925. She was the fifth of six daughters born to Irene Ophelia Thompson and John Wesley Dobbs, who were leaders in the African American community of Atlanta's Auburn Avenue area. Like her sisters, she began piano lessons at the age of seven, sang in community and church choirs, and attended Spelman College, where she began to study voice. Naturally shy, she was so nervous at her first solo appearances that she had to lean on the piano for support, but her unusual talent and quality of voice persuaded her father to fund further studies in New York. She studied with Lotte Leonard and won a Marian Anderson Award, among other scholarships, and a John Hay Whitney Fellowship, which enabled her to study in Europe.

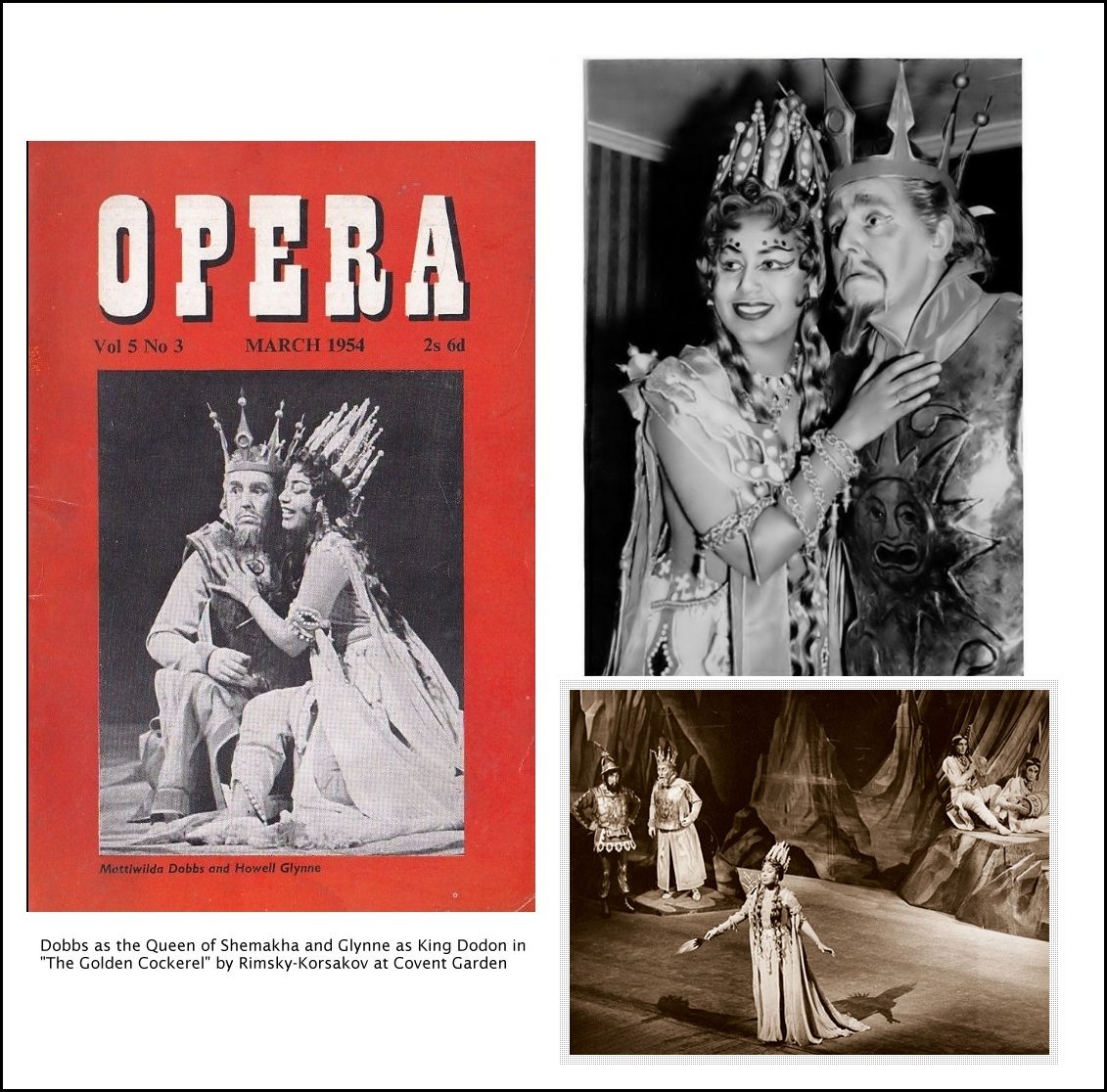

Dobbs's coloratura soprano was praised for its freshness and agility, as well as for the beauty of its tone. After winning the International Music Competition in Geneva, in Switzerland, in 1951, she sang in major festivals and opera houses throughout Europe, including La Scala in 1953. Her American debut was in 1954 at a recital in New York. She sang the role of Gilda in Giuseppe Verdi's Rigoletto for her debut with the Metropolitan Opera in 1956. Although Marian Anderson, a black opera singer from Pennsylvania, had preceded her to that stage in 1955, Dobbs was the first African American woman to be offered a long-term contract by the Met; she sang twenty-nine performances, in six roles, over eight seasons.  Although she remained close to her family and performed in Atlanta several

times, personal as well as professional considerations prevented Dobbs from

making the city her home. She lived in Spain with her first husband, Luis

Rodriguez, who died of a liver ailment in June 1954, fourteen months after

their wedding. She then married Bengt Janzon, a Swedish newspaperman, just

before Christmas 1957. Her family attended the wedding, but because of the

stir an interracial marriage would have caused in the segregated South, the

ceremony was held in New York, and the new couple made their home in Sweden.

Bengt Janzon did not visit Atlanta until 1967. (He died in 1997).

Although she remained close to her family and performed in Atlanta several

times, personal as well as professional considerations prevented Dobbs from

making the city her home. She lived in Spain with her first husband, Luis

Rodriguez, who died of a liver ailment in June 1954, fourteen months after

their wedding. She then married Bengt Janzon, a Swedish newspaperman, just

before Christmas 1957. Her family attended the wedding, but because of the

stir an interracial marriage would have caused in the segregated South, the

ceremony was held in New York, and the new couple made their home in Sweden.

Bengt Janzon did not visit Atlanta until 1967. (He died in 1997).Following the example set by African American performer and activist Paul Robeson, Dobbs refused to perform for segregated audiences. In Atlanta she could have performed in African American churches or colleges, but she was not able to perform for a large integrated audience until the Atlanta Municipal Auditorium was desegregated in 1962, when she was joined onstage and given a key to the city by Mayor Ivan Allen Jr. It was the first of many performances in her home city. Before the organization of the Atlanta Opera in 1985, Dobbs performed in operas produced and directed by the acclaimed opera singer Blanche Thebom, and in 1974 she sang at the gala marking the inauguration of her nephew Maynard Jackson as mayor of Atlanta. [See my Interview with Blanche Thebom. BD] In 1974, after retiring from the stage, Dobbs began a teaching career at the University of Texas, where she was the first African American artist on the faculty. She spent the 1974-75 school year as artist-in-residence at Spelman College, giving recitals and teaching master classes. In 1979 Spelman awarded honorary doctorates to both Dobbs and Marian Anderson. Dobbs continued her teaching career as professor of voice at Howard University, in Washington, D.C. She served on the board of the Metropolitan Opera and on the National Endowment of the Arts Solo Recital Panel. Dobbs continued to give recitals until as late as 1990 before retiring to Arlington, Virginia. -- New Georgia Encyclopedia [photos

added for this presentation]

|

As the years went by, I also gathered interviews with many of the artists

who came to town, and included portions of them whenever appropriate.

This was the part which I did on my own. They were practically never

assigned, and I did them on my own time and at my own expense. But I

enjoyed doing them, and listeners almost always responded favorably.

I also sought out a few musicians who did not sing in Chicago when I could

meet them, and arranged telephone interviews such as the one presented here.

As the years went by, I also gathered interviews with many of the artists

who came to town, and included portions of them whenever appropriate.

This was the part which I did on my own. They were practically never

assigned, and I did them on my own time and at my own expense. But I

enjoyed doing them, and listeners almost always responded favorably.

I also sought out a few musicians who did not sing in Chicago when I could

meet them, and arranged telephone interviews such as the one presented here. BD: They don’t just grow on trees!

BD: They don’t just grow on trees! BD: Is there anything we can do to encourage

more attendance at more recitals?

BD: Is there anything we can do to encourage

more attendance at more recitals? MD: No, no. I sing the same way in every

opera house. Of course in recitals you use your voice differently,

but in every opera house I sing the same way. I don’t try to force

because I have a certain volume and that’s it. I can’t give any more.

You really don’t hear yourself as it’s going out, as the people out there

hear it is, but I don’t think one should ever try to force. You give

what you can give, and that’s it. You try and project it so it can go

out. The Metropolitan was very big. The new house I’ve never sung

in, and it’s even bigger. The old house was around 3,800 seats, but

it had very good acoustics. People used to say they were good.

When I compare it with other places, I think that it had very good acoustics.

MD: No, no. I sing the same way in every

opera house. Of course in recitals you use your voice differently,

but in every opera house I sing the same way. I don’t try to force

because I have a certain volume and that’s it. I can’t give any more.

You really don’t hear yourself as it’s going out, as the people out there

hear it is, but I don’t think one should ever try to force. You give

what you can give, and that’s it. You try and project it so it can go

out. The Metropolitan was very big. The new house I’ve never sung

in, and it’s even bigger. The old house was around 3,800 seats, but

it had very good acoustics. People used to say they were good.

When I compare it with other places, I think that it had very good acoustics.

BD: Is there any way that we can encourage more

people to go to operas and concerts?

BD: Is there any way that we can encourage more

people to go to operas and concerts?

MD: Oh yes. That’s the only thing that gets

you through! When I told you that you have to love it, you love it because

it’s fun. You have to enjoy singing, and you have to say that’s what

I want to do. Oh yes, it’s fun, even when you’re scared to death or

you’re not feeling well. Once you start, it helps you to feel better.

It really does!

MD: Oh yes. That’s the only thing that gets

you through! When I told you that you have to love it, you love it because

it’s fun. You have to enjoy singing, and you have to say that’s what

I want to do. Oh yes, it’s fun, even when you’re scared to death or

you’re not feeling well. Once you start, it helps you to feel better.

It really does!|

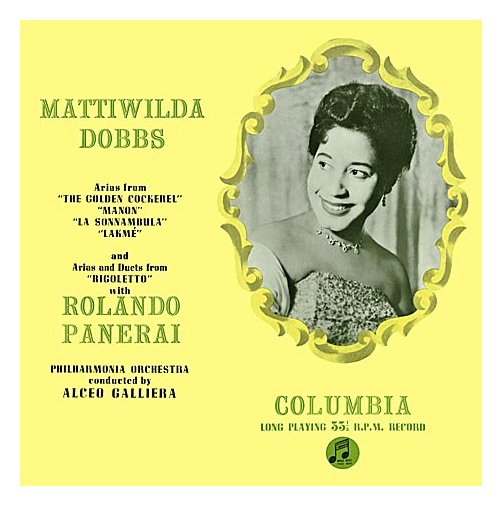

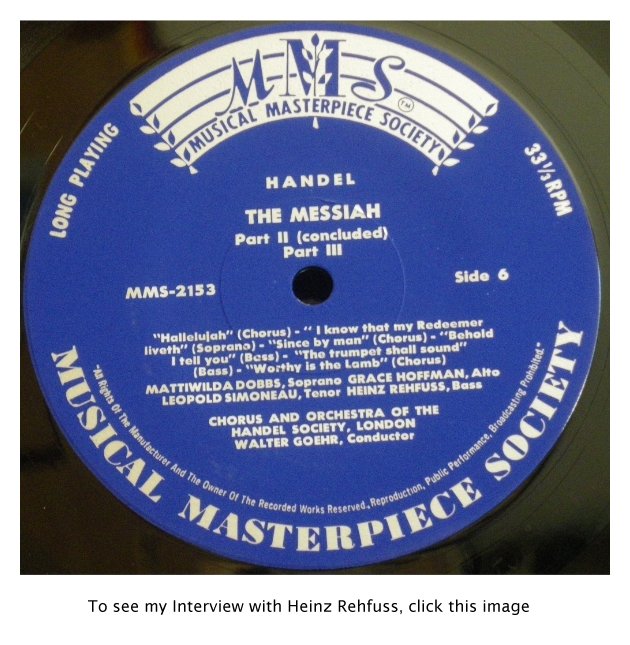

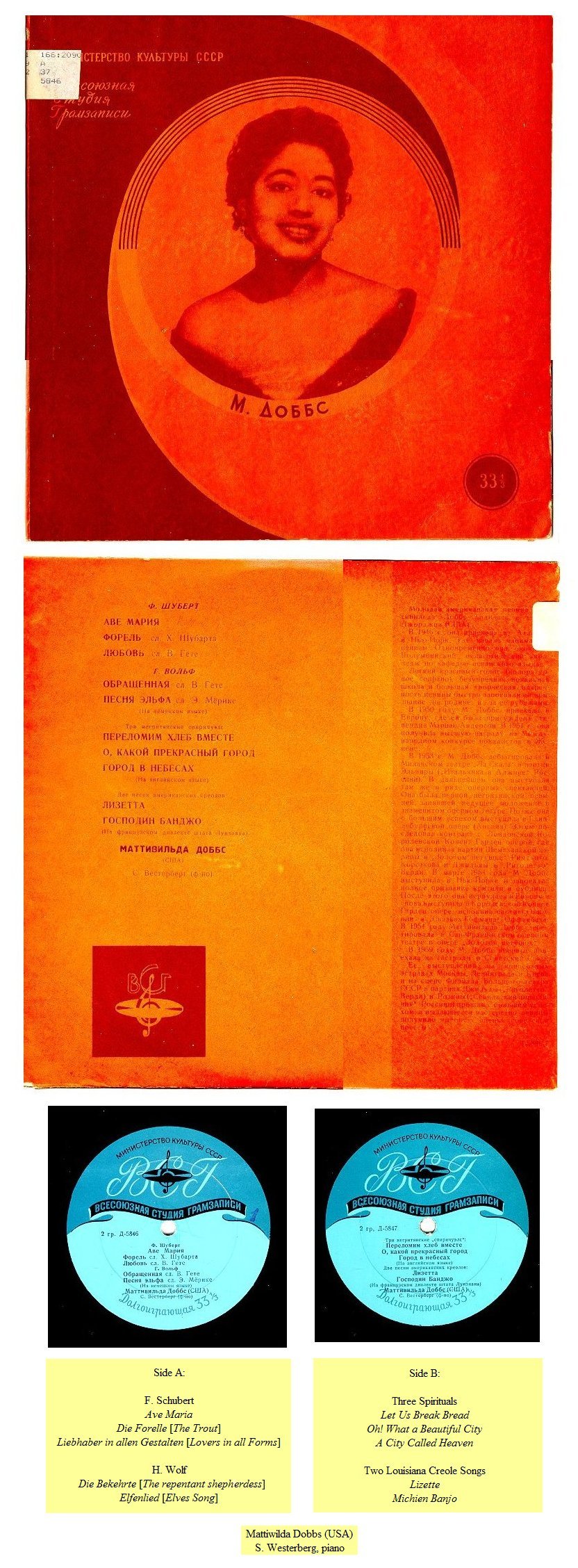

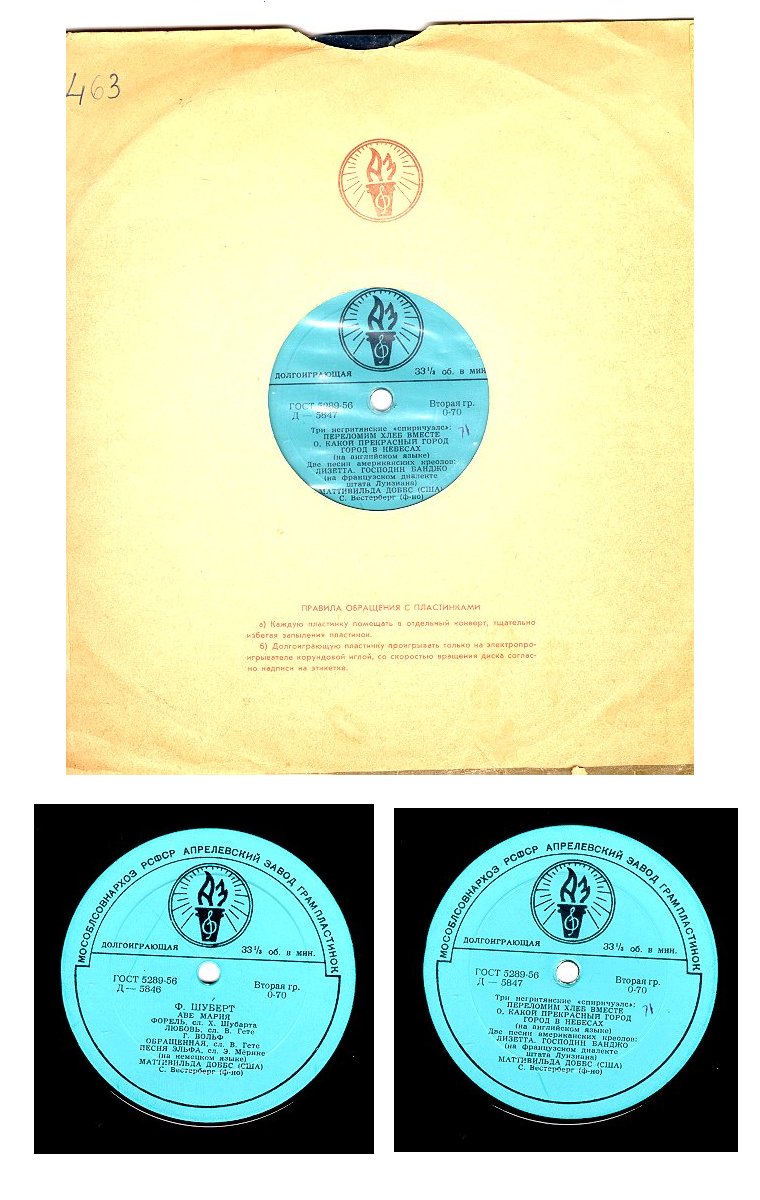

I was eventually able to locate

and purchase two copies of this 10" LP.

The first one (pictured above) had a jacket but no sleeve. The second (shown below) had a sleeve but no jacket. Both of the discs were in excellent shape. The labels are slightly different, indicating two different issues.

|

© 1994 Bruce Duffie

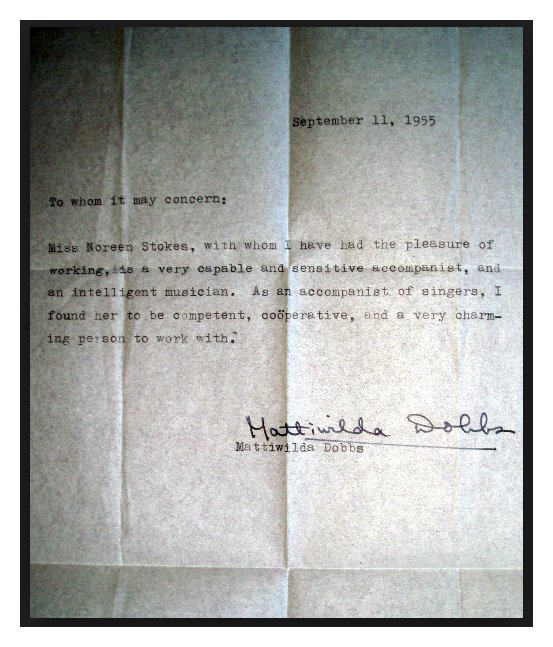

This conversation was recorded on the telephone on March 28, 1994. Portions were broadcast on WNIB the following year, and again in 2000. This transcription was made in 2014, and posted on this website at that time. My thanks to British soprano Una Barry for her help in preparing this website presentation.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website, click here.

Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM, as well as on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio.

You are invited to visit his website for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.