|

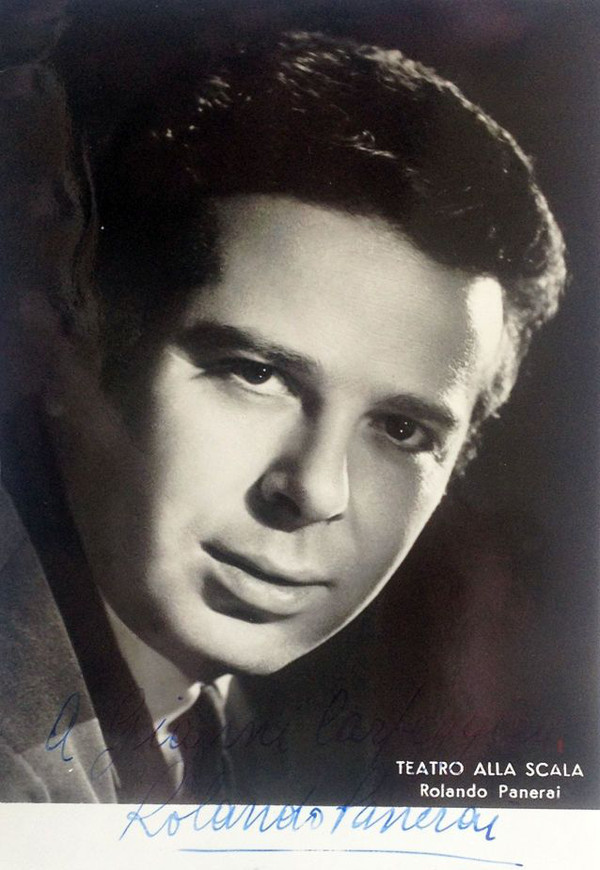

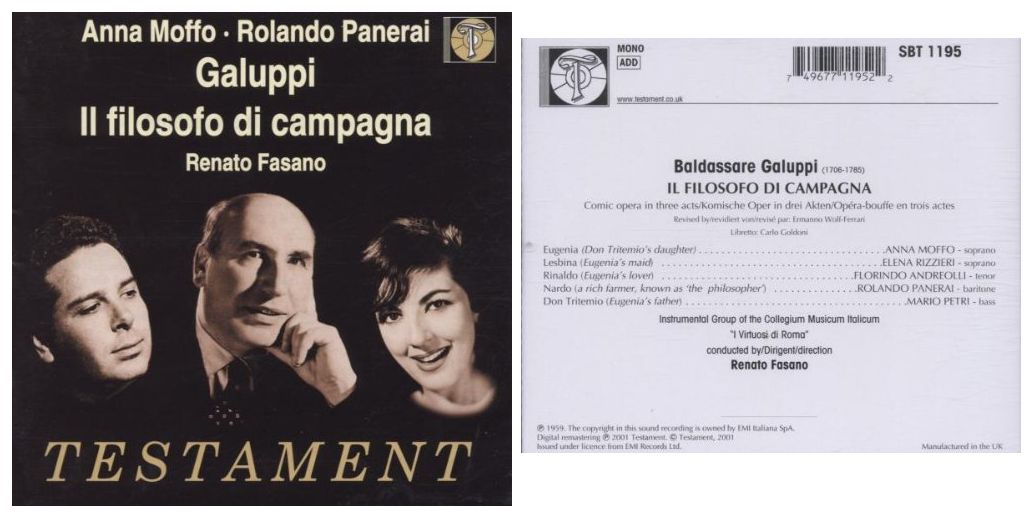

Rolando Panerai (born 17 October 1924) is an Italian baritone,

particularly associated with the Italian repertory. He was born in Campi

Bisenzio, near Florence, Italy. Panerai studied singing at the Florence Conservatory with Raoul

Frazzi, and then in Milan with Armani and Giulia Tess. After winning first

prize in the Adriano Belli Singing Competition at Spoleto, he made

his operatic stage debut in 1946 as Enrico / Lucia di Lammermoor at

the Teatro Dante in Campi Bisenzio, followed the next year by the role

of Faraone (Pharaoh) in Rossini’s Mosè at the San Carlo,

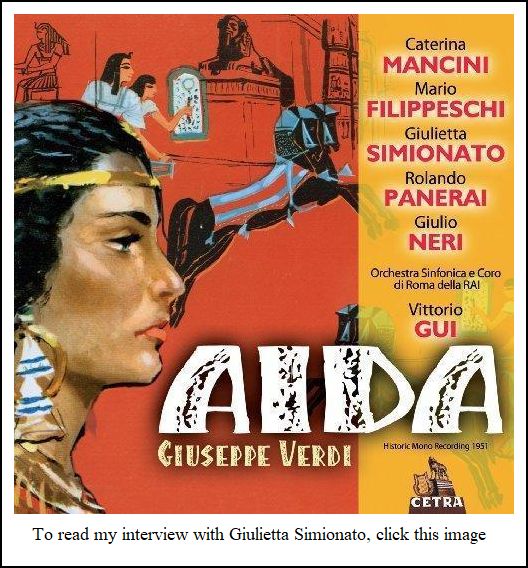

Naples. During 1951 he undertook a number of leading baritone roles, notably

those in Aroldo, Giovanna d’Arco, and La battaglia

di Legnano, in Italian radio broadcasts marking the fiftieth anniversary

of Verdi’s death. He sang in several of the major Italian opera houses,

and made his debut at La Scala, Milan as the High Priest / Samson et

Dalila.

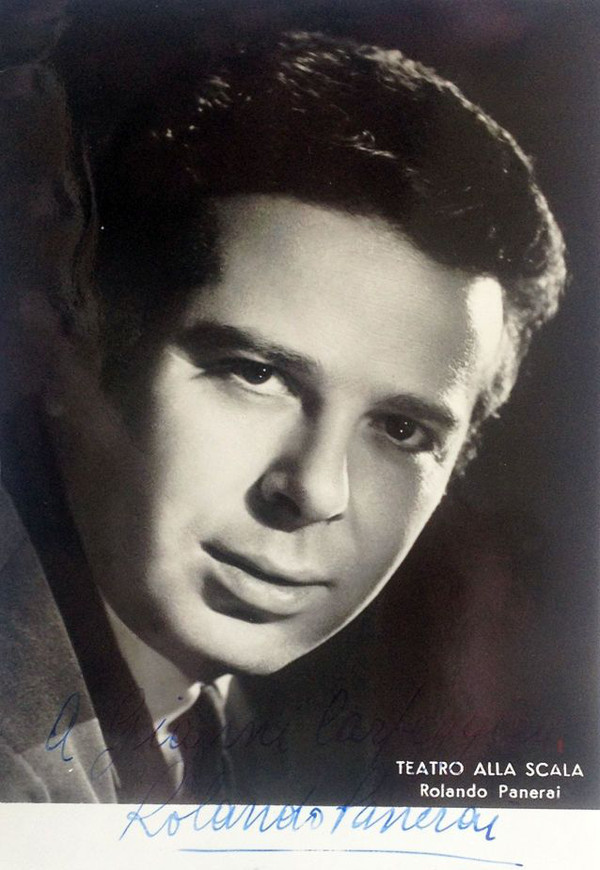

Note that Panerai sings the title role in this recording

made in March, 1983.

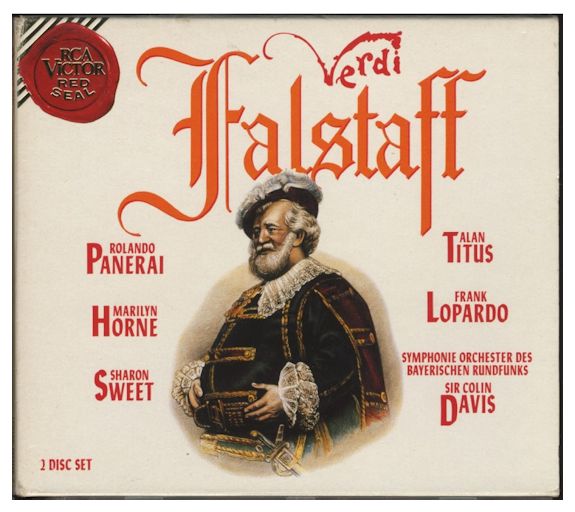

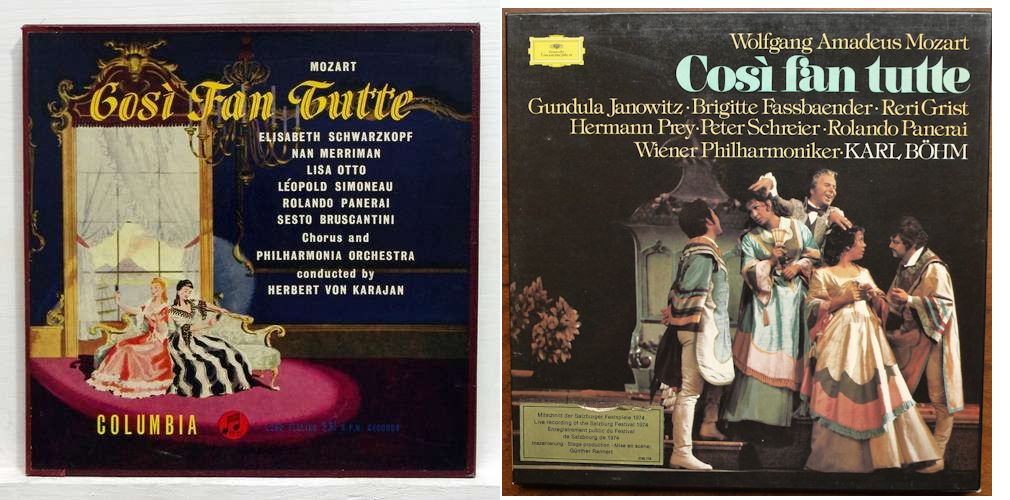

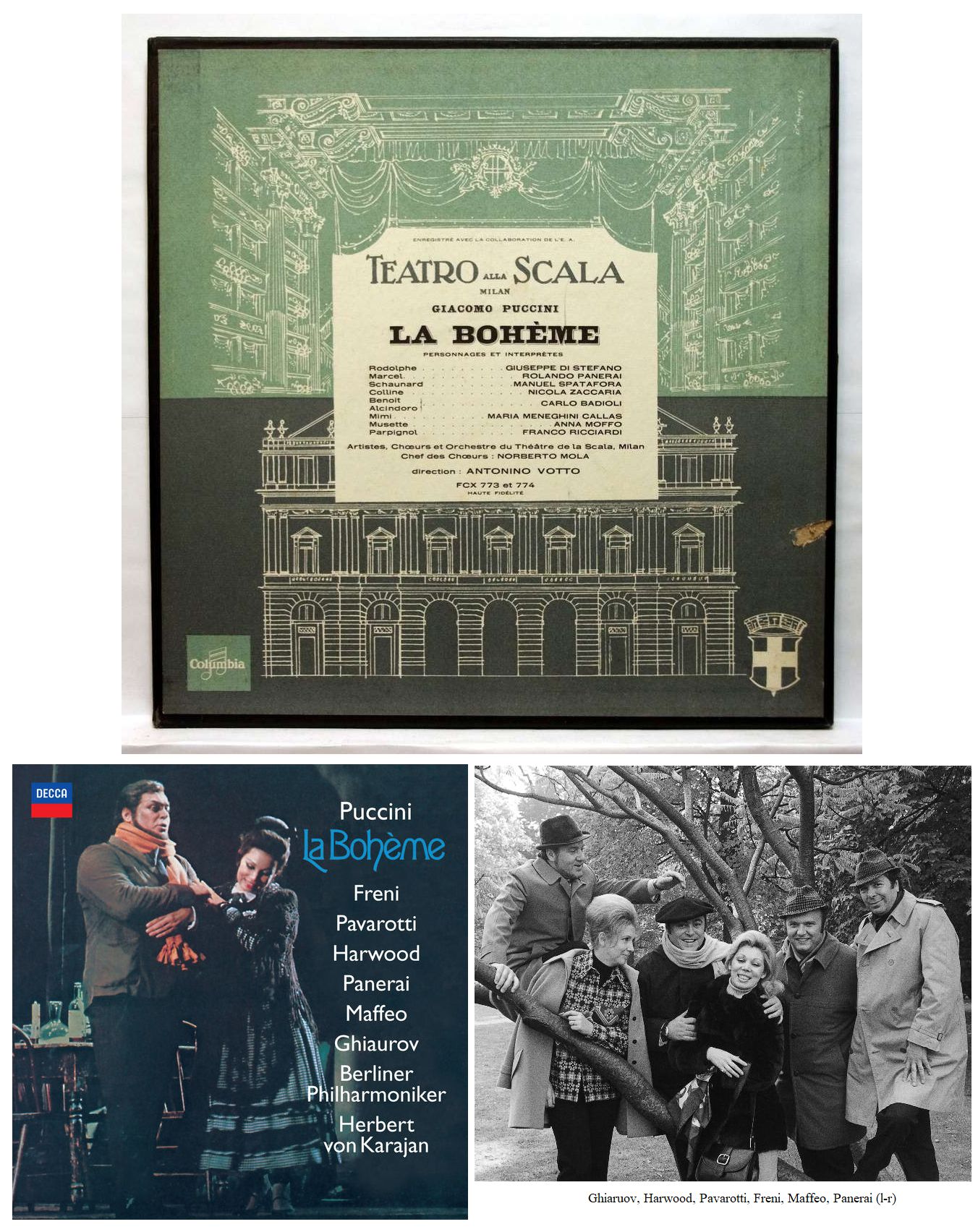

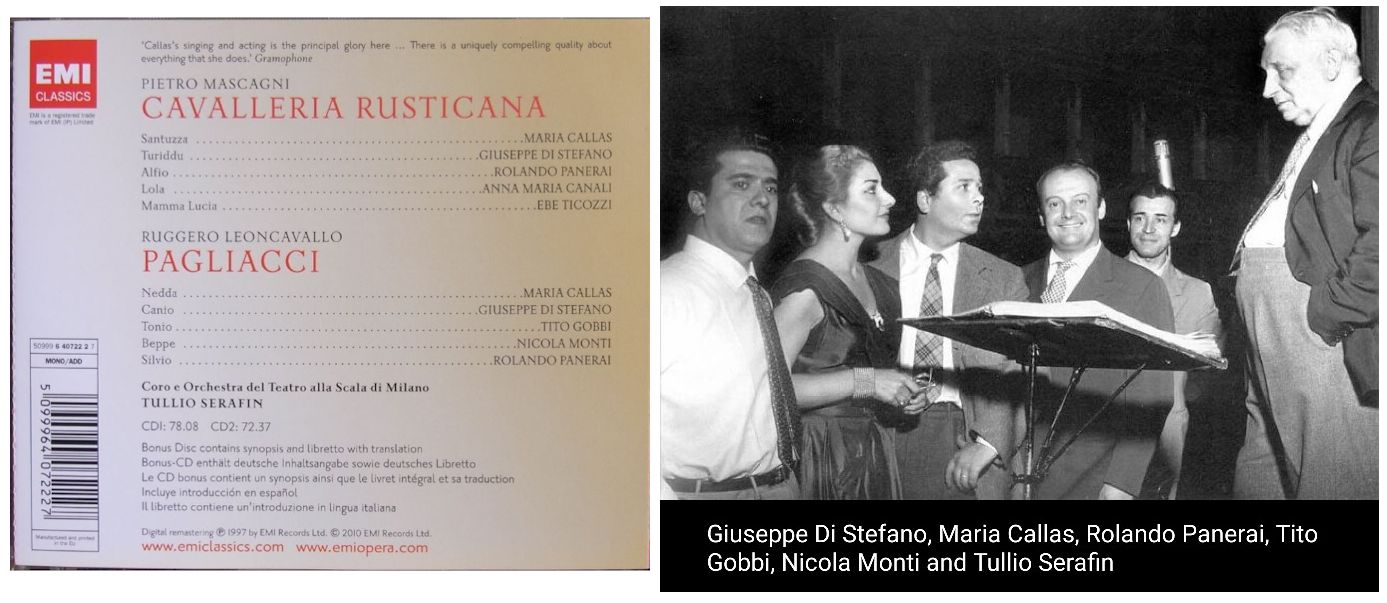

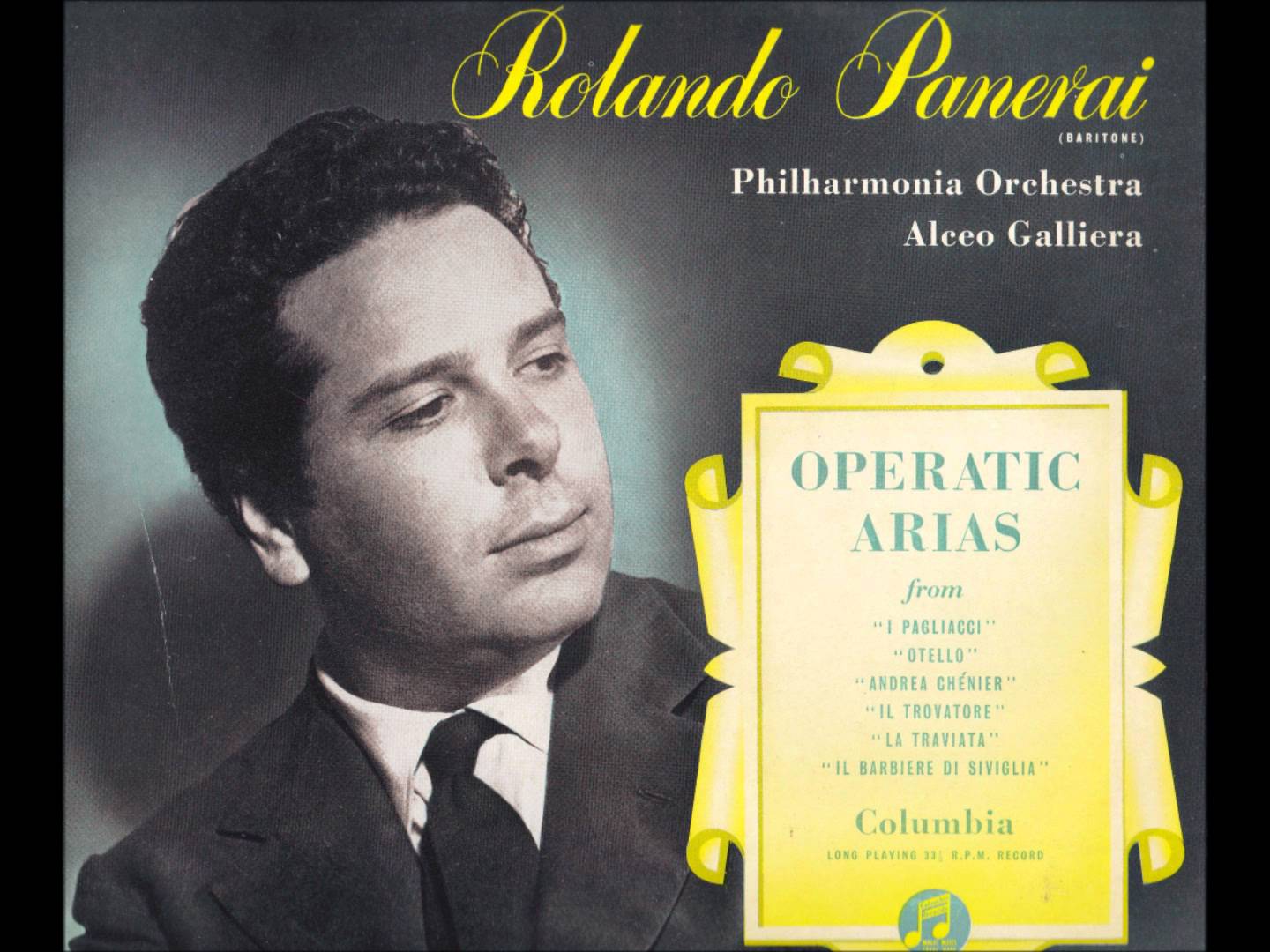

At the Salzburg Festival Panerai first appeared in 1957 as Ford / Falstaff. He returned often, as Guglielmo / Così fan tutte (1958–1959), Masetto / Don Giovanni (1960–1961, 1968–1970), Paolo / Simon Boccanegra (1961), Malatesta / Don Pasquale (1971–1972), Don Alfonso / Così fan tutte (1972, 1974–1977) and Ford once again (1981–1982). He also appeared at many other European festivals, including Aix-en-Provence, the Caracalla Baths in Rome, Glyndebourne, the Florence Maggio Musicale and Verona. In 1958 Panerai made the first of many appearances at the Vienna State Opera, and in the same year made his American debut with the San Francisco Opera, singing Marcello / La Bohème and the Figaros of both Mozart and Rossini. He first sang at the Royal Opera House, London in 1960, as Rossini’s Figaro with Giulini conducting, returning there to sing Don Alfonso, and the title roles in Falstaff and Don Pasquale in 1984 and Dr Dulcamara / L’elisir d’amore in 1985 and 1990. Panerai’s career was very long-lasting and took him to many international opera houses, including those of Amsterdam, Athens, Barcelona, Berlin, Frankfurt, Johannesburg, Lisbon, Monte Carlo, Munich, Paris, Rio de Janeiro, San Francisco, Stuttgart and Zürich, as well as all the principal Italian houses. His repertoire featured most of the great Verdi baritone roles, including the title part in Rigoletto, di Luna / Il trovatore, Posa / Don Carlo, Amonasro / Aida and Germont père / La traviata. He sang the title role in Gianni Schicchi at the Florence Maggio Musicale in 1988, in Chicago in 1996, and again in Florence in 2006; Count Douglas in Mascagni’s rarely-heard Guglielmo Ratcliff at Catania in 1990; Dulcamara in Barcelona in 1998; and Germont père for Italian television in 2000, with Zubin Mehta conducting. A most engaging and versatile stage presence enhanced Panerai’s

voice, a relatively light high baritone. He recorded extensively, and can

be heard on several major recordings featuring Maria Callas. -- Biography above by David Patmore, from the

Naxos website (text only - photo and links added for this presentation)

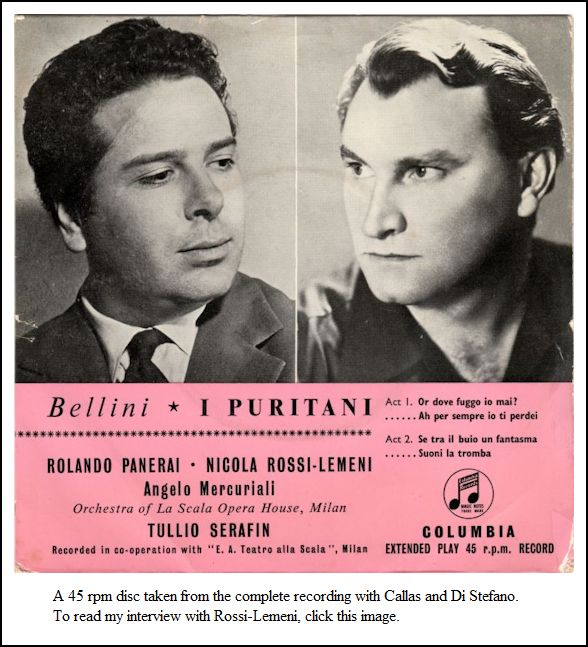

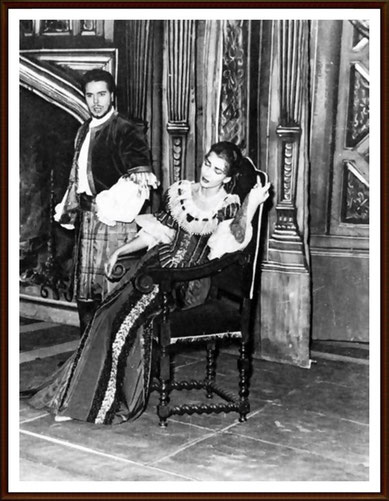

[From a different source] Panerai often partnered with Maria Callas and Giuseppe di Stefano

in Il Trovatore [shown directly below], Cavalleria Rusticana,

Pagliacci, Lucia di Lammermoor, I Puritani

and La Bohème. He also recorded a notable Sharpless in Madama

Butterfly, opposite Renata Scotto and Carlo

Bergonzi, and Germont La Traviata, opposite Beverly Sills and Nicolai

Gedda. He recorded excerpts from Rigoletto with Mattiwilda Dobbs, and later

committed the complete role to disc. He plays Ford in three different recordings

of Verdi's Falstaff, opposite interpreters of the title role

Tito Gobbi, Dietrich

Fischer-Dieskau, and Giuseppe Taddei (the latter on video, under Herbert

von Karajan). He also recorded the title role. He can be heard singing

Wagner in Italian translation, the role of Amfortas in a recorded performance

of Parsifal with Maria Callas as Kundry and Boris Christoff as Gurnemanz.

He can be seen on video as Ford, Figaro in The Barber of Seville,

Rigoletto, Silvio in Pagliacci, and in concert in A Bolshoi

Opera Night (DVD). He is active as a teacher in masterclasses, and

has directed Il Campanello dello Speziale, Gianni Schicchi,

La Traviata, La Bohème, Rigoletto

and Il Trovatore.

|

|

Giovanni Malatesta (died 1304), known, from his lameness, as Gianciotto, or Giovanni, lo Sciancato, was the eldest son of Malatesta da Verucchio of Rimini. From 1275 onwards he played an active part in the Romagnole Wars and factions. He is chiefly famous for the domestic tragedy of 1285, recorded in Dante's Inferno, when, having detected his wife, Francesca da Polenta (Francesca da Rimini), in adultery with his brother Paolo, he killed them both with his own hands. He captured Pesaro in 1294, and ruled it as podestà until his death. |

BD: Do you prefer playing evil characters

or comic characters?

BD: Do you prefer playing evil characters

or comic characters?

RP: No!

RP: No!

BD: It’s too bad we can’t put

an old head on young shoulders.

BD: It’s too bad we can’t put

an old head on young shoulders. BD: Were performances with Maria Callas

mostly unforgettable?

BD: Were performances with Maria Callas

mostly unforgettable?

BD:

Are there times when it gets even better and better and better?

BD:

Are there times when it gets even better and better and better?

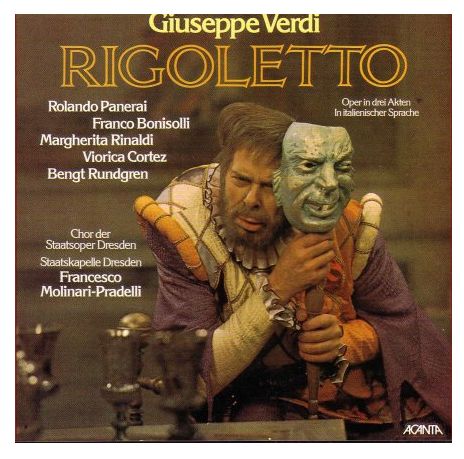

© 1996 Bruce Duffie

This conversation was recorded in Chicago on October 31, 1996. Portions were broadcast on WNIB in 1998, and again in 1999 and 2000. This transcription was made in 2018, and posted on this website at that time. My thanks to British soprano Una Barry for her help in preparing this website presentation.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website, click here.

Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM.

You are invited to visit his website for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.