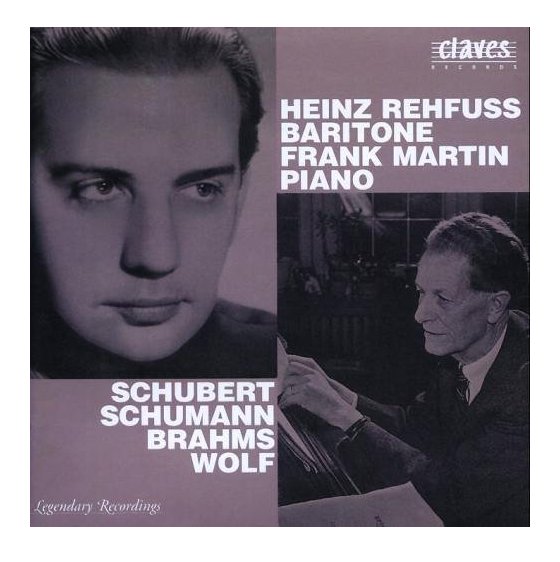

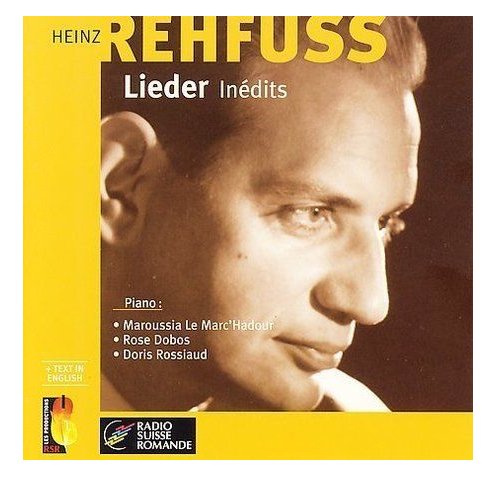

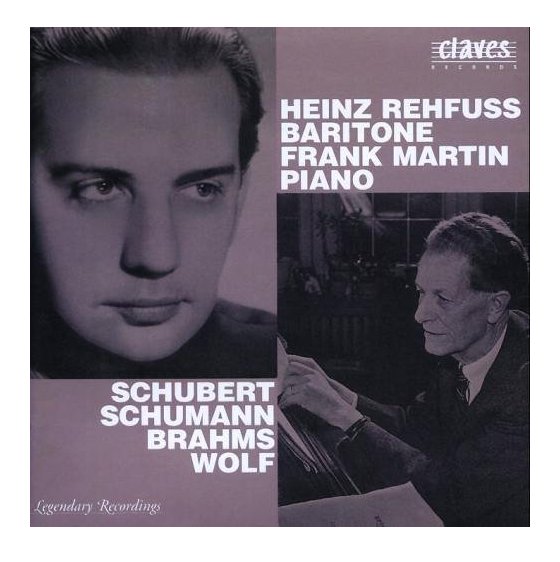

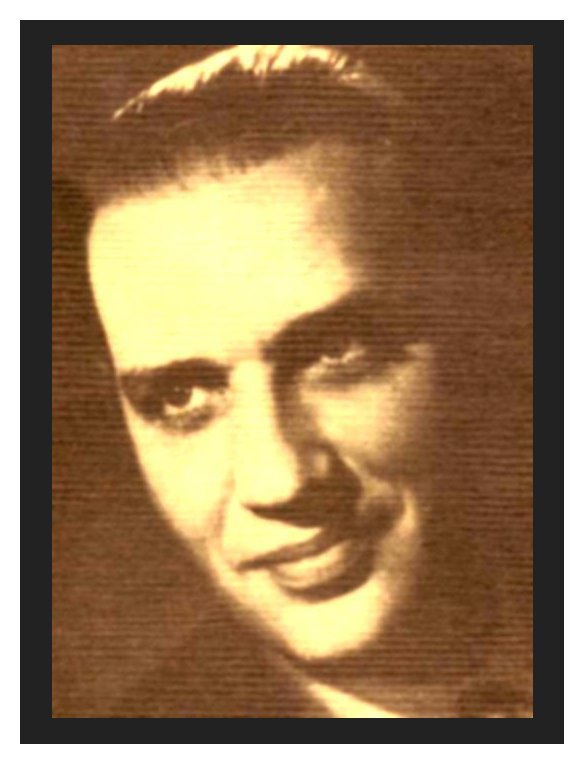

Bass - Baritone Heinz Rehfuss

A Conversation with Bruce Duffie

|

Heinz Refhuss

Born: May 25, 1917 - Frankfurt am Main, Germany

Died: June 27, 1988 - Buffalo, New York, USA

The German born, Swiss, and later American bass-baritone, Heinz (Julius)

Rehfuss, studied with his father, Carl Rehfuss (1885-1946), a singer and

a teacher, and with his mother, Florentine Rehfuss-Peichert, contralto. The

family moved to Neuchâtel, and Rehfuss became a naturalized Swiss citizen.

Heinz made his professional debut in opera at Biel-Solothurn in 1938. Then

he sang with the Lucerne Stadttheater (1938-1939) and the Zürich Opera

(1940-1952). He subsequently was active mainly in Europe and in America.

He became a naturalized American citizen.

Rehfuss taught voice at the Montreal Conservatory in 1961 and in 1965 was

on the Faculty of the State University of New York at Buffalo. In 1970 he

was a visiting professor at the Eastman School of Music in Rochester, New

York. He also toured Asia, giving vocal recitals in India and Indonesia.

He was successful mainly in dramatic roles, such as Don Giovanni and Boris

Godunov, but he was also a gifted Bach singer.

|

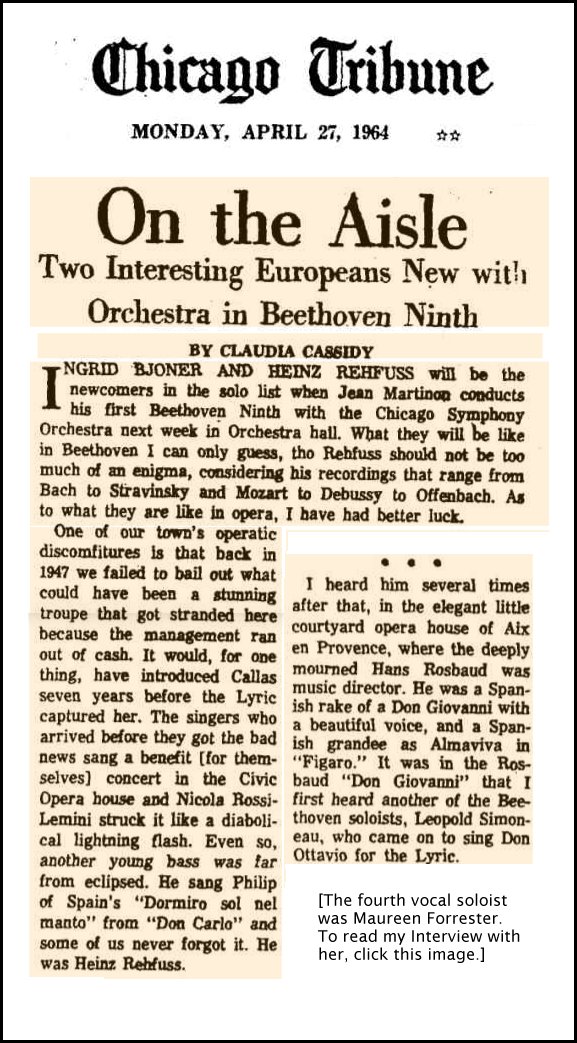

In April of 1987, just a month before his 70th birthday, I

contacted Heinz Rehfuss and he allowed me to call him on the telephone for

an interview. As can be seen below, we had a wonderful conversation.

His English was excellent, though, as is often the case, it was sprinkled

with unintended mannerisms and the occasional grammatical error. I

have fixed most of those, but some were simply so charming that they have

been left in this text.

I had admired his recordings for many years, and we talked about his career,

but we began with his pedagogical work . . . . . . .

Bruce Duffie: Let us start out with the teaching.

You’re professor of music at Buffalo?

Heinz Rehfuss:

Yes. I’m here now, for the twenty-second year. I joined in 1965

and at the same time I was also teaching at the Conservatoire de Musique

de Québec, Montreal, and sometimes at Eastman, Rochester, New York.

BD: You’re teaching both singing and stage acting?

BD: You’re teaching both singing and stage acting?

HR: Singing and

stage acting, and also I was staging some opera productions here with the

students.

BD: I read in your

biography that you got involved in opera productions very early in your career.

HR: Yes, because

I studied with the very famous opera stage director, Otto Erhart. He

was for a long time in Buenos Aires at the Teatro Colón, and I was

his assistant for a while.

BD: Why would somebody

who was primarily a singer want to also get involved with stage action so

early?

HR: That’s because

my parents both were singers, and I wanted to do something else. I

was attracted by the stage and by opera, naturally, so I decided to study

stage directing, and also I was also doing stage design at the beginning.

I was only eighteen years old, and continued to do that but the vocal possibilities

were stronger. You know what it is when professional groups of singers

have a young fellow telling them what they should do in performing and acting!

Naturally it was much easier to start singing, and then singing happened

to be successful. So I prevailed there, but I continued to do as much

directing as time permitted.

BD: You indicate

in that period it was not very good for a youngster to be directing older

singers, but now we seem to have quite a number of very young stage directors

with a lot of well-thought-out ideas. Has the pendulum swung completely

to the other side?

HR: I’m not so

absolutely sure about that because singers who have their so-called traditions

don’t want a young fellow to tell them what to do, especially because they

have much more advanced and revolutionary ideas about staging. They

get very uncomfortable if somebody comes and pushes them away from their

old ruts.

BD: [Laughs]

Should someone come and gently nudge singers out their ruts?

HR: Those young

people who have good ideas will prevail anyhow. Some who have ideas

which are a little bit too far-fetched will not be successful. But

I suppose a conscientious singer who thinks that a young stage director has

a new approach and something which is defensible will be willing to follow

his ideas! But some really are so eccentric that the singers almost

rebel if they have to sing upside down, or hang from the air. I did

a performance of Intolleranza by

Luigi Nono in Venice at the Festival, and I was suspended in the air in a

net. It’s not too comfortable to sing that way. It’s not the

way you feel it should happen in order for you to get your breath control

and everything.

BD: At what point

does the stage direction become too much, too far-fetched?

HR: That’s difficult

to say. Naturally with some opera houses

— particularly in Germany, Austria, or France, and even in Italy

— definitely I would say the singers themselves are young, and

try to understand what the stage director is trying to experience with them.

They are more willing than in a traditional opera house — talking

of Germany, like Munich or Berlin or Vienna — where they

don’t have the interest, and maybe not the time, to rehearse accordingly

— except when it is the festival and there’s a lot of time to

prepare the show. They don’t like to be too much pushed into experiences

and experiments.

BD: Are you basically

pleased with the ideas that are going around in stage direction today?

HR: Yes, I think

so. Some opera houses are really famous and renowned for being experimental,

and you expect these things to happen there. I saw such performances

when I had a sabbatical last year. I was touring Europe and getting

a little bit of information about what’s going on, and I was rather pleased

and amazed because opera is something which is not a museum art. It

has to go with your time, and this includes the traditional, not just the

contemporary composers.

BD: So there has

to be new life breathed into the old operas as well as the new operas?

HR: Right.

But somebody said if you dust, you should not take away the polish when cleaning

up the traditions. If you go really down to the bare bones, there’s

no more life and energy remaining.

* *

* * *

BD: We were talking

a little bit about stage direction, so let me ask you about singers.

How have singers changed in the last twenty, thirty, forty, fifty years?

HR: I think they

are coming back now more to the ‘bravura’ style, and they are digging out

again operas with a lot of coloratura and florid passages. The human

voice as a ‘bravura’ instrument is getting more accepted and requested now

in the repertoire, so you see the renaissance of the Donizetti operas, of

the Bellini operas, and all the Rossini works.

BD: Is that a good thing?

BD: Is that a good thing?

HR: I think so

because singers really have to work harder on their technique, and probably

they last longer that way.

BD: How do you

get young singers to take the time to build a career carefully instead of

trying to emerge too quickly?

HR: Yes, that’s

a good question because if a young singer is very promising, has a talent,

has a good voice, and has an acceptably ready technique, they are sometimes

pushed into parts they are not ready for yet. This goes for their interpretation,

and also technically and volume-wise because the young voice has to develop

organically and cannot be pushed too soon into the Strauss operas or some

of the ‘verismo’ works where you really tense up too much to produce a big

sound. This is also because some of the opera houses are acoustically

not the best for young voices to mature.

BD: You sang all

over the world. Did you adjust your technique at all from house to

house?

HR: I tried to.

Also, it’s interesting... For example, here in America you have an

overlapping of all these different multi-cultures, which is excellent.

But in Europe, since I’m from Switzerland, I was fluent in French, German,

and Italian, so I could see what they do in French opera houses, in Italian

opera houses, in German and Austrian opera houses, and the style is very,

very different from country to country. The Italians go more for generous,

big voice, beautiful voice, legato singing in the repertoire. Sometimes

the same operas are very differently produced in these three countries

or cultural levels.

BD: Is that because

the expectations of the audiences are different in these three cultures?

HR: Yes, and I

think it’s also because of certain traditions. In Europe you have two

different big systems. In Germany, for example, they have a so-called

‘repertoire’ theater where the

whole company of singers sing according to availability of repertoire.

But in Italy they have the ‘stagione’

principle where they have good singers who are very famous for certain parts

and they sing these parts all over, touring from town to town.

BD: Which is better,

or are they just different?

HR: I don’t know.

The ‘stagione’

is probably better because the young singer who has proven his possibilities

in a part can mature, singing it several times in different cities under

different conductors and stage directors. They may grow more organically

than somebody who is pushed into a part which is maybe not yet the best for

him. He cannot judge absolutely what is the best for him because he

has an appetite and he wants to get access as soon as possible to the parts.

He would like to sing but he’s not always counseled correctly by the conductor

or by the stage director, or even by the voice teacher.

BD: I would think

the voice teacher would be looking out for each singer!

HR: That’s right,

but sometimes the voice teacher is somewhere else, and he gets a letter or

they send him a program and reviews, but the singer loses some of the contact

with the teacher because the teacher is far away. He might just attend

the opening night and give some advice, but he has not the possibility to

keep the young singer under steady control. Also the young singer who

wants to follow up and improve his technique and overcome short comings sometimes

goes to another teacher in the city where he’s employed. That may be

an opportunity for him, and he can have another idea about him.

BD: In your career,

how did you decide which roles you would accept and which roles you would

decline?

HR: I was very

cautious. I was never the Italian baritone. I was more, what

they call in Germany, the ‘Cavalier Baritone’ — the

Mozartian parts and the dramatic parts, but not the very heavy parts.

BD: No Wagner?

HR: I sang Wolfram

and Klingsor, and Kothner in the Meistersinger,

but never, never the heavy stuff. You sing with your muscles, and the

more you work them out, the stronger they get. It’s like tennis, or

like weight-lifting. After a certain while you get stronger, and you

can touch repertoire which you were not physically and intellectually ready

for at the beginning of your career.

BD: Is singing

a performance like an athletic contest?

HR: To a certain

extent! Singing an opera lasting five hours, like some Wagnerian parts

that are very exacting, helps your stamina. You need a lot of strength

and endurance.

* *

* * *

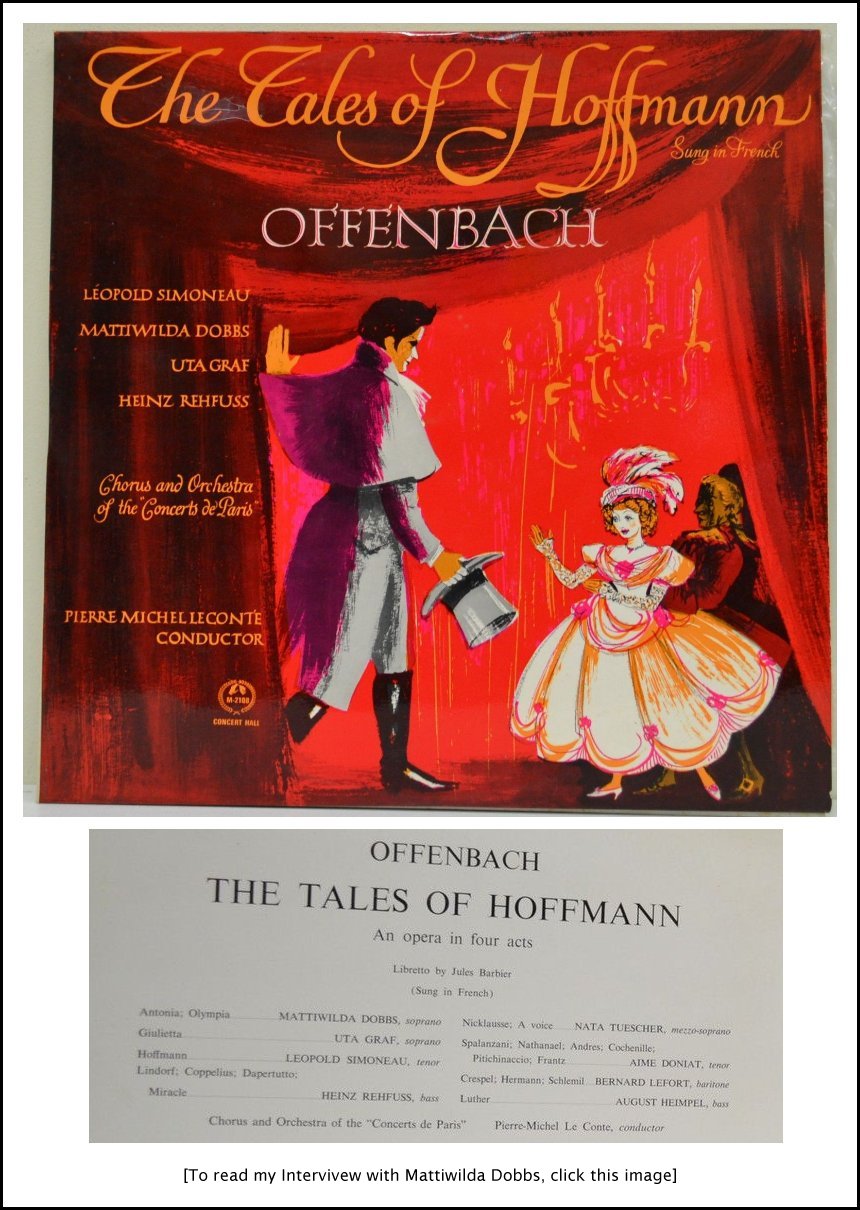

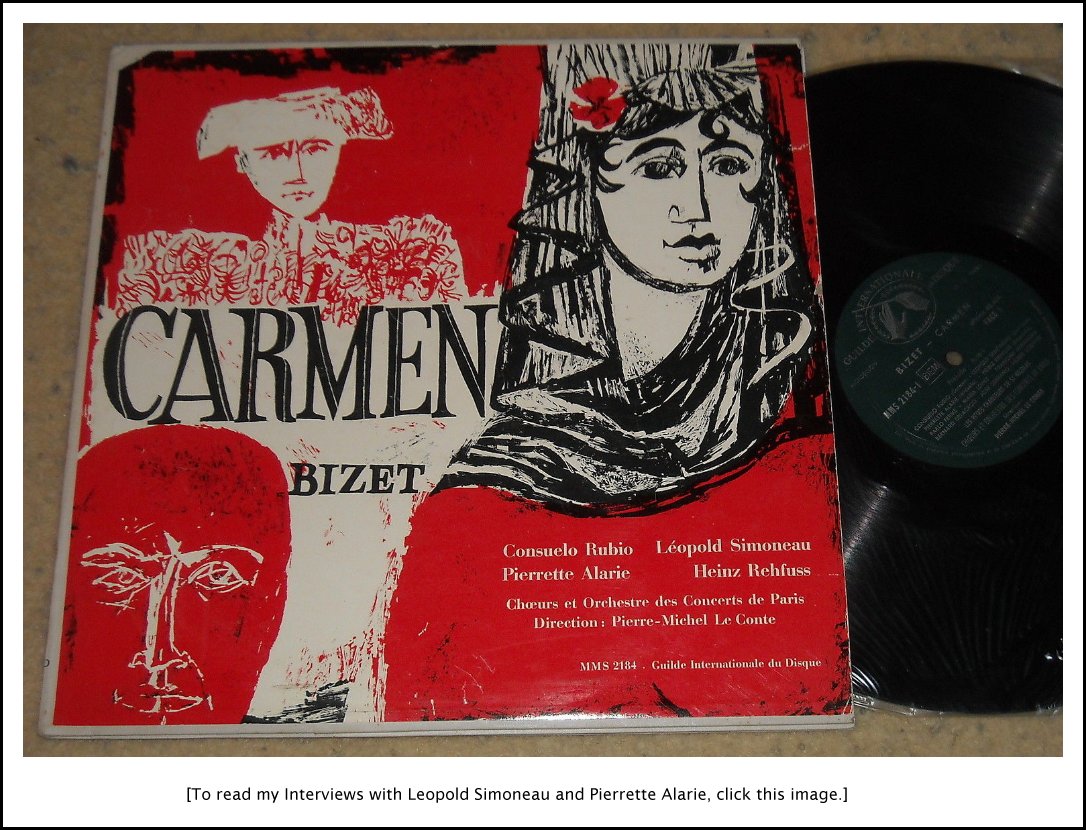

BD: You’ve recorded

several French roles, so let us speak about a couple of those. First

the roles in Hoffmann.

HR: Very often

they are divided between a baritone and a bass-baritone and a high-baritone.

Dapertutto is usually sung by a high-baritone, especially if the aria is

sung in the original key. Sometimes they transpose it if it’s a lower

voice. Dr. Miracle is rather a character bass, and the other

one in the first act is always the buffo. So we must be very versatile,

but if within the scope of your voice you can adjust it, it’s better to have

one person to singing all the three characters, and even the character in

the prelude. It’s a little bit more difficult naturally, but there

is no problem for Hoffmann because he stays in the same tessitura.

Even for the four female parts, one is dramatic soprano, the doll is a coloratura,

and in the last act it is a lyric soprano. But some singers have that

versatility and technical flexibility to do them all.

BD: Do you feel

all of these characters are different sides of the same coin, and by portraying

them with the same singer it brings that out?

HR: It seems to

me to be the original idea of Offenbach when he wrote it.

BD: It becomes

quite a ‘tour de force’ then for the soprano and the baritone!

HR: It certainly

is.

BD: Who is the

real hero of that opera?

HR: Probably E.

T. A. Hoffmann, the writer because he is, let’s say, the German Edgar Allan

Poe. That’s the magic and the phallic undertone which goes through

the whole opera. You know that the opera even was banned because some

people said it was bringing mishap to the theaters. The first time

it was performed in Vienna, there was the famous fire where the opera house

burned and there were a lot of casualties. For a very long time, some

people had apprehension to put in the repertoire. It was a doomed opera.

It came back in the ’20s when Max Rheinhart and his

people were doing extraordinary stagings, and there was Klemperer who was

conducting the Sadler’s Wells performances. Then the doom was forgotten

and the opera houses of the world over had to courage to play and put it

in the repertoire.

BD: There are a

couple of versions of this opera, are there not?

HR: Yes.

It’s not really two versions, but several. There is a possibility to

finish with the Venice Act and do the Munich Act before because it’s stronger.

And there is also a version where the Muse at the end has a long monologue

and he’s extending when the chorus has gone away off stage. Then there’s

a version which finishes with the students singing at the end. Basically

Offenbach couldn’t finish it completely because he died shortly before it

was first performed. In France they gave always the opera with the

spoken dialogue, but a student of his wrote the recitatives so it could be

given at the Grande Opéra. There was a habit in Paris that what

was given at the Opéra-Comique had dialogue, while what’s given at

the Grande Opéra everything has to be sung. So when they performed

it at the Opéra, he added the recitatives. The same thing that

happened with Carmen.

BD: Which is better?

Which is the stronger performance?

HR: I personally

would think that the recitatives are better because it’s very seldom that

singers speak a very good dialogue. He loses a little bit of the stage

presence.

BD: The projection?

HR: Yes, projection.

Also it’s not so good for the voice because if you continue after an aria

and suddenly talk, you must carry much more than if you continue to keep

your breath control, continuing and going the opera singer’s way. You

will notice, for example, in the Italian repertoire there is very seldom

spoken dialogue. Everything is recitative because the singer wants

to stay afloat with his voice control.

BD: Then singers

who are singing these roles in Hoffmann,

Carmen or The Magic Flute should be taught how

to speak like actors?

HR: I think so,

yes. There’s the exception of Magic

Flute which was, at Mozart’s time, almost like a musical nowadays.

It was performed for the enjoyment of the public. Also Mozart, besides

his genius, kept the tunes very popular. There’s a mixture of grandeur

in the chorus and in the so-called Egyptian scenes. Then the contrast

of Papageno and Papagena, with a lot of jokes, and they sing relatively easy

tunes. Naturally they were rather singing-actors than singers who have

to talk dialogue.

BD: Then let me

ask a balance question. Is opera art or entertainment?

HR: Oh, it should

be both. It should be very artistic and entertaining. Some are

more stilted due to their libretto and due to the character of the composer.

If you think of the Ring, naturally

Wagner did not have an idea to entertain his public. He wanted to elevate

them to almost a cult, and make it a celebration. But on the other

hand, staying with Wagner, in his Meistersinger

he would want maybe to entertain and be more down to the man in the street.

After all, it’s a comedy.

BD: You say Wagner

wanted to elevate the audience to a height. Was he trying to elevate

them to praise Wagner or to praise music or to praise God, or what?

HR: I don’t know.

It is blasphemous, but I think he wanted to squarely praise himself.

It’s dangerous to say that, you know, but he wasn’t a very humble or modest

man. He was not only a composer and a philosopher, but he was a visionary.

I don’t know any composer who built his own theater, and it’s still there

after a hundred years. Mozart got his Salzburg Opera but that was done

by his admirers for the grandeur of his genius. He was from Salzburg,

which by the way, he didn’t like at all! Strauss and Hoffmansthal and

Max Reinhardt and others created a Mozart Center there in 1920.

BD: You sang some

Mozart...

HR: Oh yes. I did Don Giovanni, I did the

Count, and in the ’50s I was the Don Giovanni at the

Aix-en-Provence Festival. I did recording of it and also Le Nozze di Figaro. That was at

a time when Rosbaud was taking over, and he was an excellent Mozart interpreter.

HR: Oh yes. I did Don Giovanni, I did the

Count, and in the ’50s I was the Don Giovanni at the

Aix-en-Provence Festival. I did recording of it and also Le Nozze di Figaro. That was at

a time when Rosbaud was taking over, and he was an excellent Mozart interpreter.

BD: Tell me the

secret of singing Mozart.

HR: Mozart is so

complete because you have to know not only the libretto but also the essence

and the style. It’s so specific, and I contend that if you can sing

Mozart you are ready for almost everything because everything is included

— bel canto, drama, philosophy. He was the most complete

genius. Who else wrote the perfect symphony, the best chamber music,

the best art songs and oratorios, and also operas? I think he’s the

most complete of all.

BD: Are there any

others who approach Mozart — perhaps in one or two

of these areas but not in all of them?

HR: Wagner, for

example, was unique, but in opera-drama. Beethoven only wrote one opera

and was discouraged. It is a magnificent opera but he was so criticized

that he was discouraged to start again. He wrote, as you know, for

different overtures. He wrote all kinds of rearrangements. There

was ur-Fidelio [Leonora] and then another Fidelio. Probably Verdi would have

had the versatility to do everything because one of his best productions

is his Requiem, which is an oratorio.

That is very dramatic, and he wrote fantastic chamber music, but probably

due to circumstances he was forced or at least inclined to write opera because

he had to make a living. That was also Italy’s first concern to have

operatic composers. Every year produces possibly outstanding opera.

They were expecting each new production like one expects a book from a famous

author. They want the next production.

BD: Why have we

gotten away from that today — the expectation of a

new work each year, from the great composers?

HR: Are there any

really very big composers today? I’m waiting for one. Maybe in

our time, after Richard Strauss, you could expect a new production of Britten.

In Germany there are some composers, but I don’t have the impression that

the world is keeping back its breath to see what comes next from these people.

Mind you, I don’t want to put them down at all.

BD: Why have we

lost this excited-ness?

HR: Isn’t it perhaps

because opera became such an extravagantly expensive thing in our world?

To put on an opera production now, especially in this country it’s very,

very difficult. In Europe you get support from the government or city.

Here in this country you get subsidies from big enterprises, but you really

have to worry enormously before you can even think of putting on a production

— except, naturally, in opera houses like where you are in Chicago,

and New York City, and San Francisco. Now more and more opera houses

get a real solid support from the authorities, but it’s a free-enterprise

and it’s a terrible risk.

BD: In Europe where

they have the state subsidy, are they getting better opera, or is it simply

more opera?

HR: They get more

opera. If you open a newspaper all over Europe, you will see that there’s

a production every night, and sometimes two productions. These artists

are on a steady salary, and whether they sing or not they get the same pay.

This excludes some exceptional singers who attract the huge audiences.

Beside the fact that they are very expensive, they are still relatively cheap

for their producers because if Pavarotti sings or Domingo sings, naturally

the people are willing to pay a bit more. I think it was Gatti-Cazzaza

[General Manager of the Met 1908-35] who said that Caruso was the cheapest

tenor he ever had because even though he had to pay him a very high fee,

he had twice the box office income. [Both laugh] You have people

without names who may be very, very good, but the public wants to see these

happy few. They probably have them on records at home and they read

about them. It’s almost like a sport where each club has one or two

big shots who get the big money, but they also bring in the big money.

BD: So they deserve

their super-stardom, you feel?

HR: Probably, yes;

certain ones if they stay good and strong. You see, the longevity of

the voice is relatively limited because the performer is also his instrument.

So if he loses stamina or gets into problems, that’s it. A pianist

has a good technique and can play the piano, but if you have enough money

in the bank you can buy another piano. A singer cannot buy a new voice.

* *

* * *

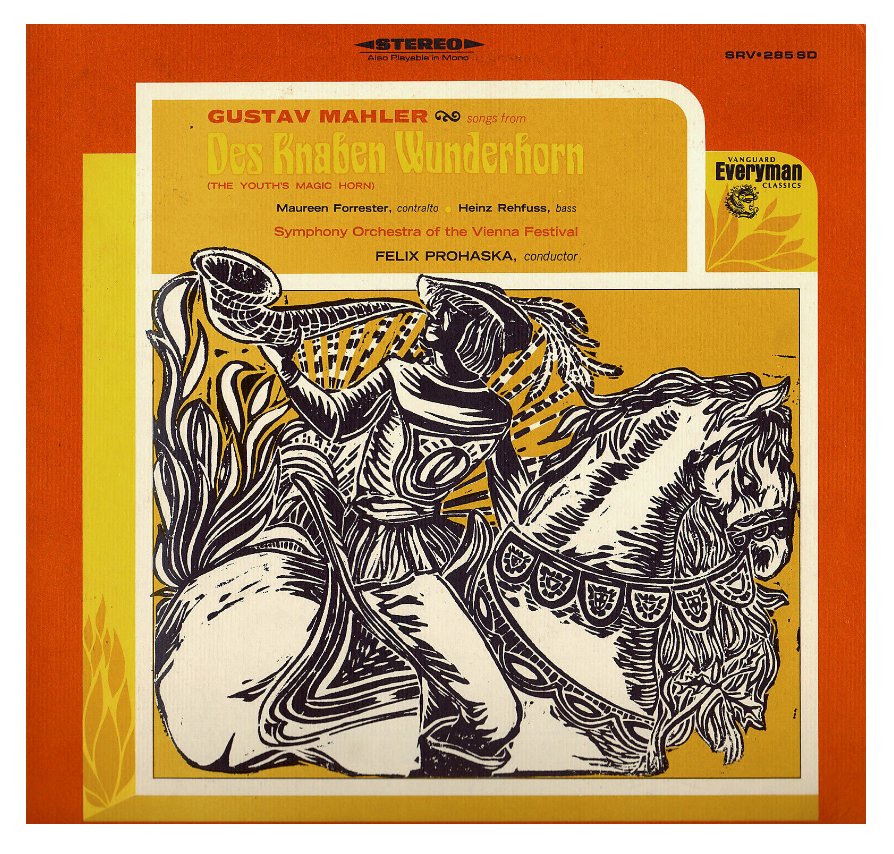

BD: Let us talk

a bit about your commercial recordings?

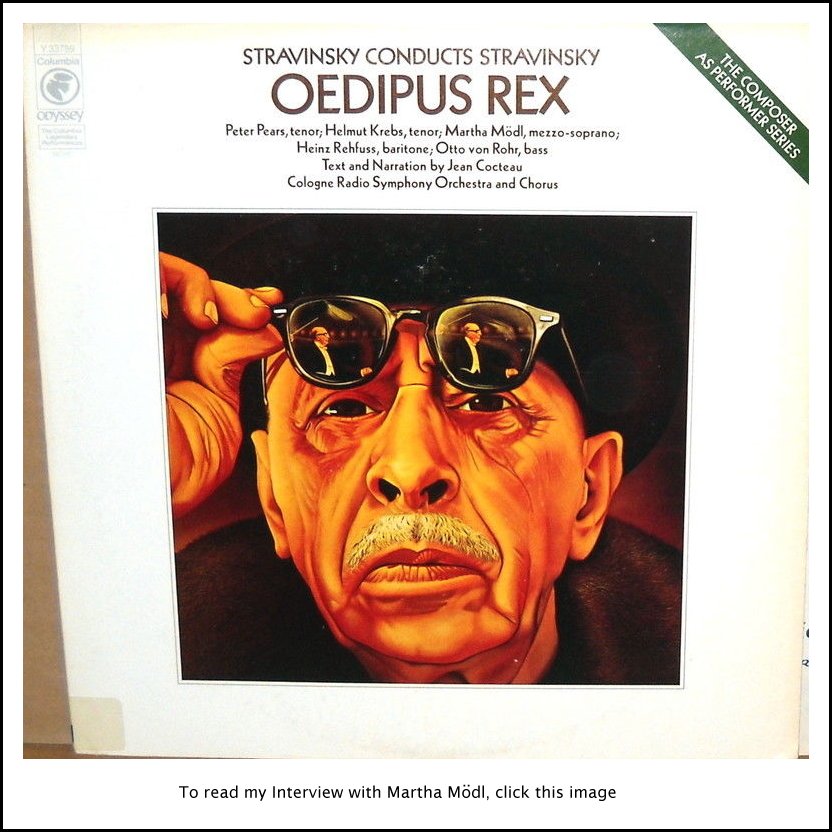

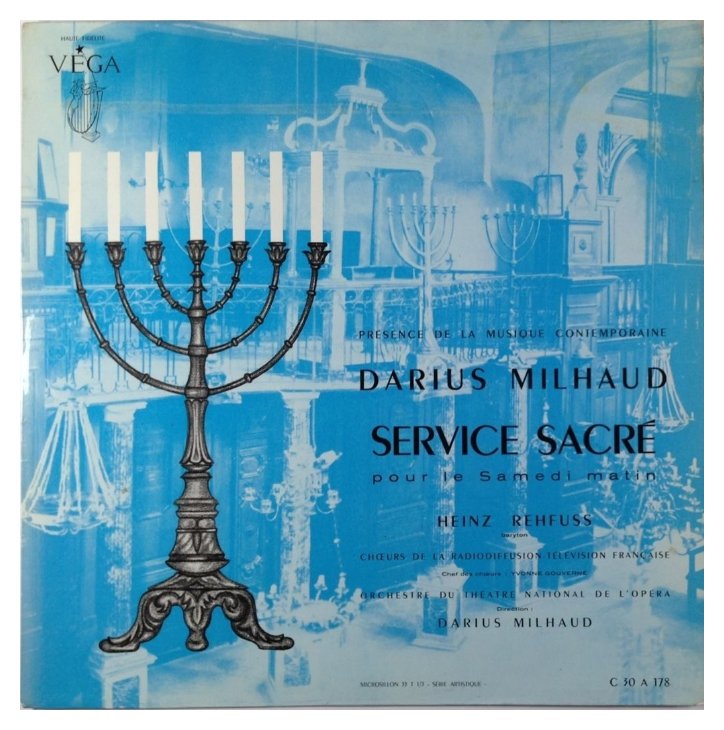

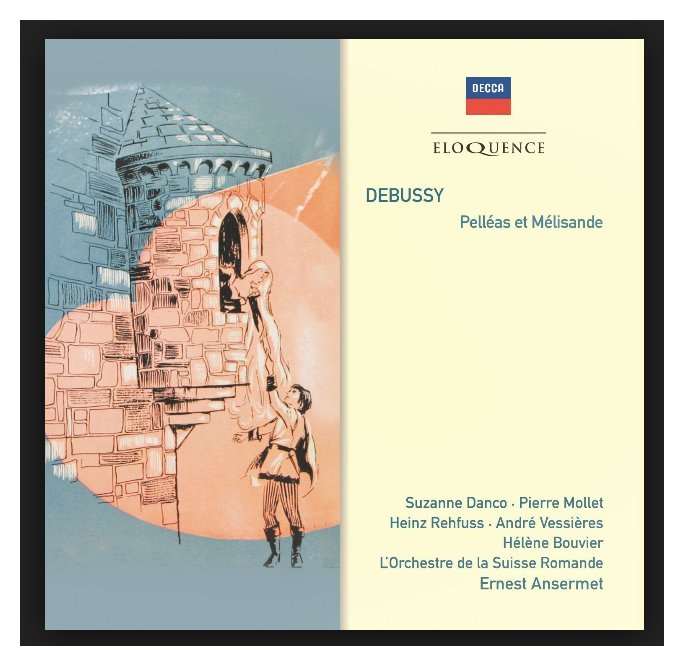

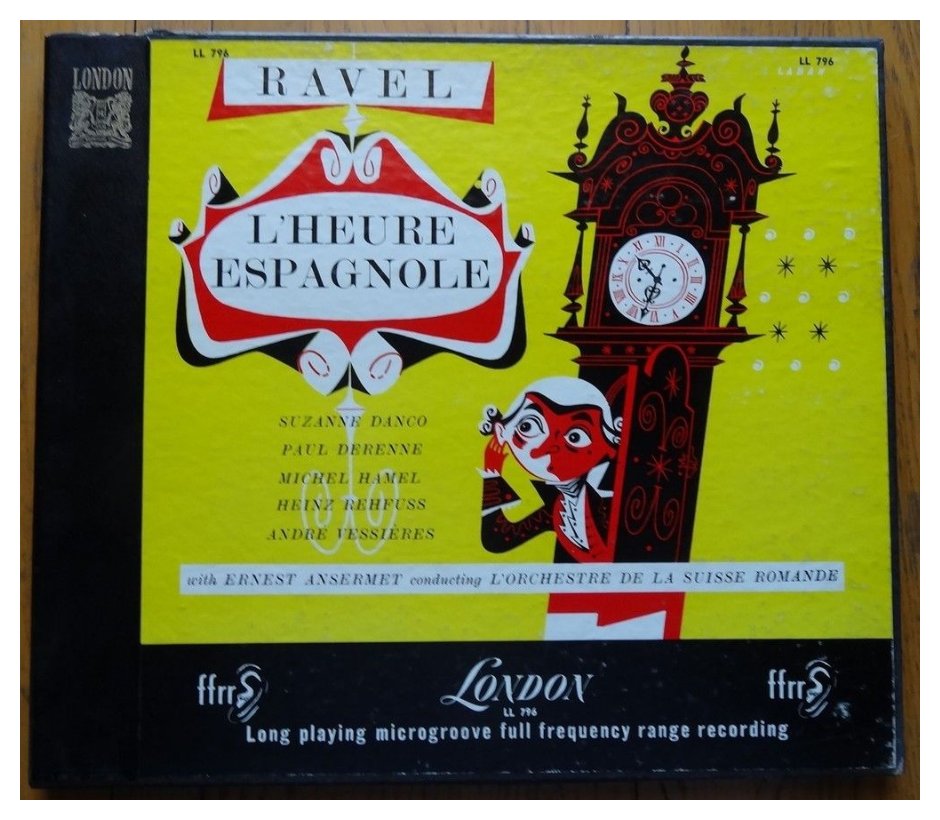

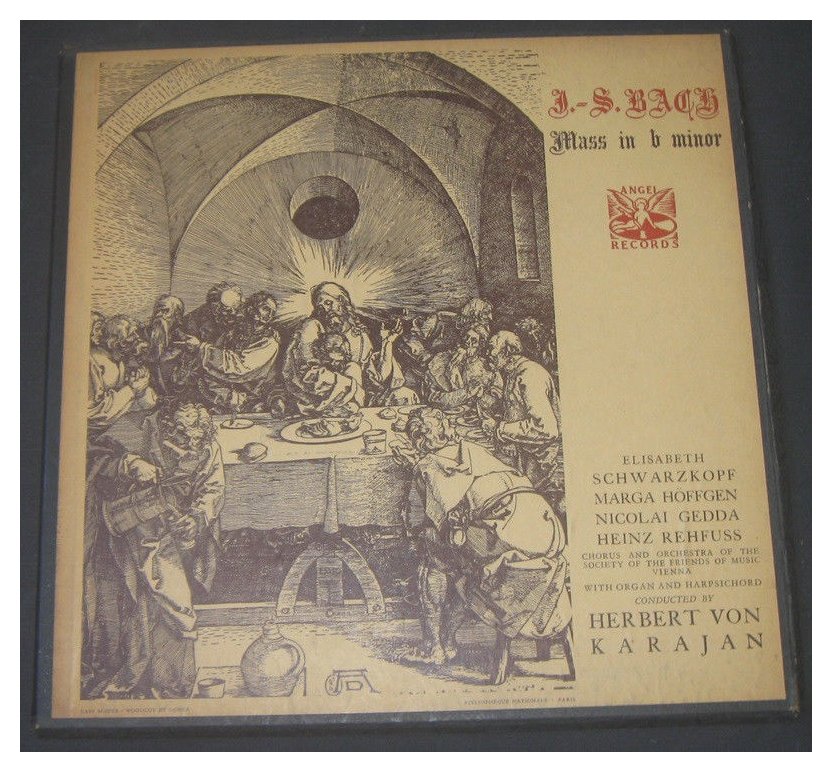

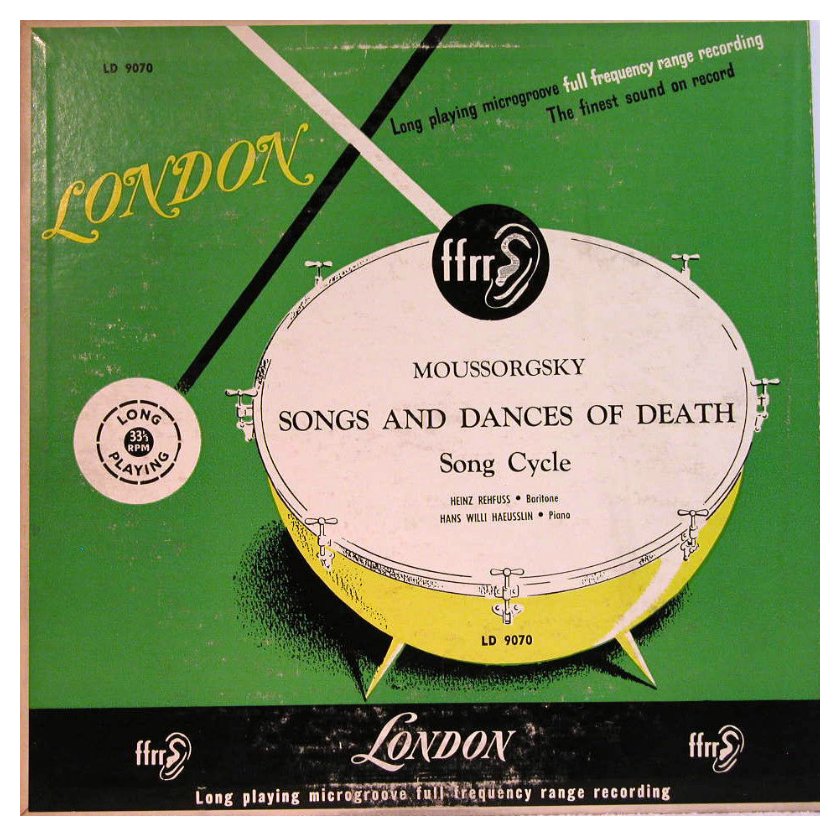

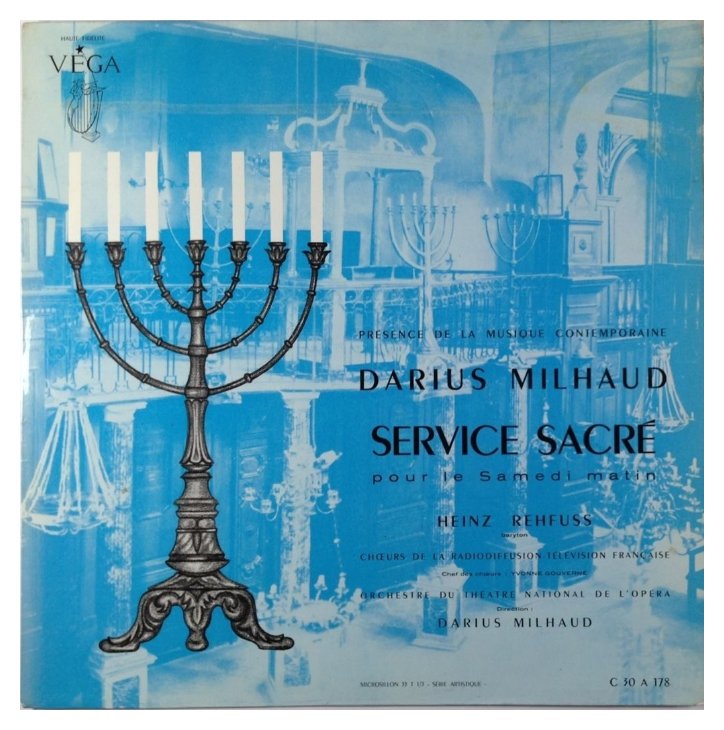

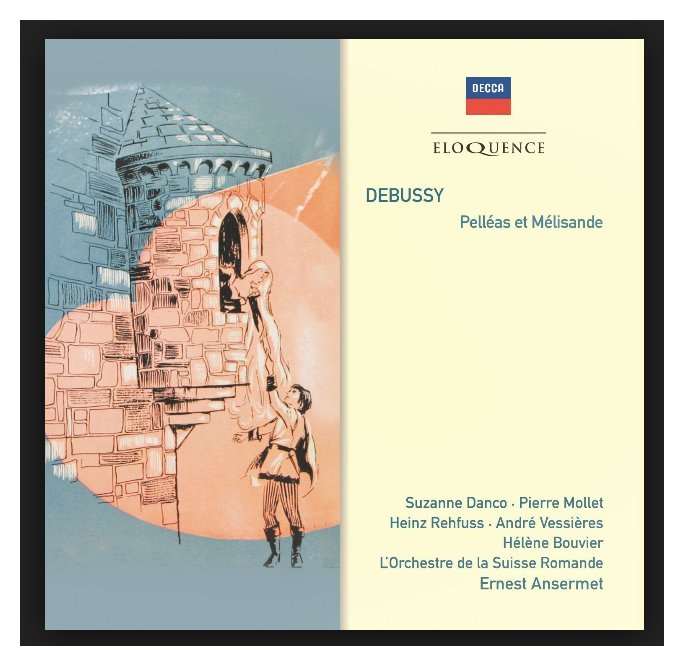

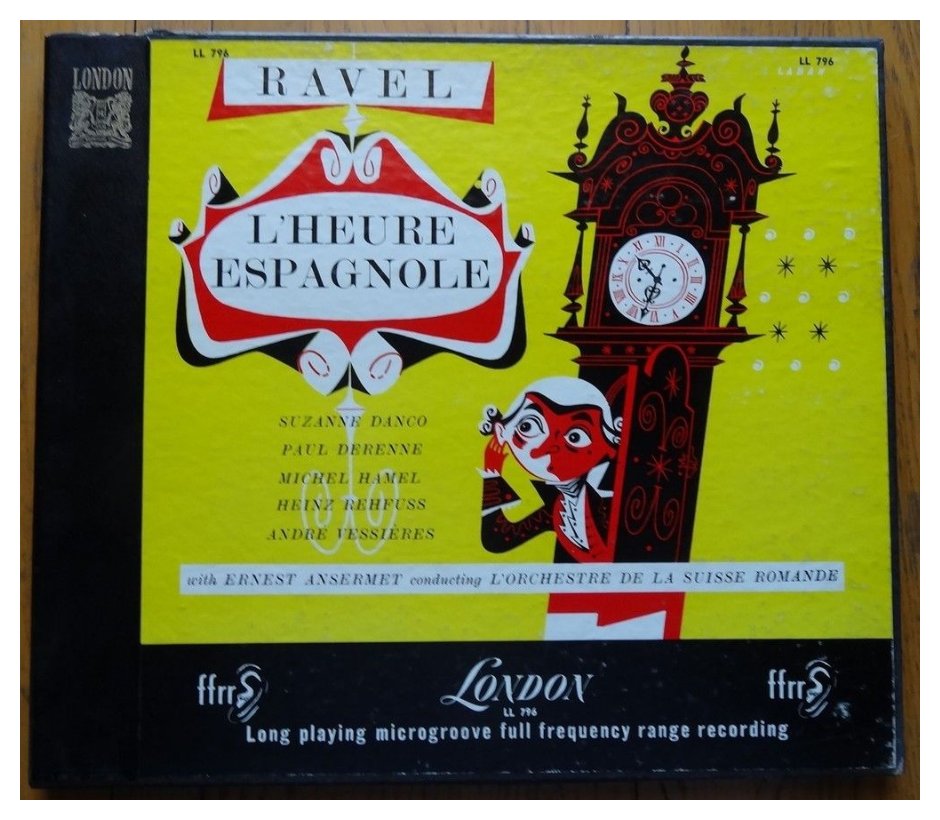

HR: I did a lot

of recordings mainly in the ‘50s, including a lot with Ansermet

such as operas, etc. for Decca. We also did some for Deutsche

Grammophon. I must have over sixty or seventy recordings, and some

won the Grand Prix du Disc like Pelléas

et Mélisande, and Les Noces

with Stravinsky conducting. I also did Oedipus Rex with Stravinsky which was

a Grand Prix du Disc.

BD: Did you enjoy

making recordings?

HR: Oh, yes.

It’s very, very important because probably I otherwise wouldn’t have had

the opportunity to come to this country. I was known by my recordings,

and that’s why people got interested in getting me over here.

BD: Did you sing

differently for the microphone than you did in live performance?

HR: I don’t think

so, no. Sometimes the technicians came and would say, “Step back,”

or “Turn your head this way,” but I think if you want to give the full extent

of your interpretation, you shouldn’t be handicapped by that little machine

which is in front of you. It’s the technician’s job to balance the

excesses which may happen. They’re pretty good at it now.

BD: Is there a

chance that a recording is too technically perfect?

HR: Some, perhaps.

I like to work for Decca, which in this country is called London Records.

They have very good people, but that’s twenty years ago, and they’re still

very, very good. They were pioneers in this FFRR system. I seldom

listen to my own recordings, but sometimes if I have friends over and they

say, “Play a record!” It’s really astonishing how technically accurate

they were already in the ’50s.

BD: Do you think

the public has become, perhaps, enamored of their recordings?

HR: Maybe... you

may be right there.

BD: Opera is, of

course, both music and drama. Do you feel it works well on a purely

aural medium?

HR: That’s naturally

something which is missing because if I analyze the word ‘personality’

— which means personal, sounds through — you

can translate through the voice enormous expression. This needs, naturally,

visual realization as well, but you can visualize something through a voice

— as when you recognize voices on the telephone. You don’t

see the person but you do get a personality through the recording.

You should compare, for example, several performances of the same opera.

It’s very, very interesting to compare them. That’s probably also the

fact that it’s kept for posterity, that you can compare what the style was

in the ’20s, and then in the ’30s,

’40s and ’50s. That is

a big evolution, and it depends also on the personality of the conductor.

Karajan recordings have the imprint of Karajan. In a Maazel recording, you

hear the personality, you don’t see it, and even if you’re not specialist,

you can feel the difference. You can feel the aura which is in the recording.

Technology has really gone so far now. Very little is lost of what

the performer gives you if you see it when you hear it.

BD: Now the technology

has gone one step farther, and we have operas on television. Do you

feel that opera works well on the small screen?

HR: It’s a little

bit too small but what is good is that it reaches a large public who otherwise

would not get in touch with opera. Or it can help others who would

probably hate it unless they have seen that it can give them enormous impact,

enormous pleasure and enjoyment. They can see it on public stations,

and also they have now videos discs and video cassettes. So I think

a lot of public will gain from that, and it will decrease the thought that

this kind of music is considered for eggheads and not for people who are

not totally in the field.

BD: Is there any

artistic value in this, or it is promotion and exposure?

HR: It’s mainly

exposure, but since it reaches such a large group of people it is also good

thing which can broaden the artistic value. Compare if you lived, say,

fifty years ago in a city somewhere in Europe, which didn’t have the money

to produce good opera. Their local opera house gave them the best that

could be achieved, but now they can see it with a world standard what really

can be achieved in an opera.

BD: So you feel

it’s worth the exposure to have operas on the television?

HR: Certainly,

because it becomes a very lively art. It becomes something which is

in our time excites not only specialists, opera buffs, but a larger audience.

The people in the rural areas would probably never think of going to an opera

because they never have it in their lives. And to attend an opera now,

you know how expensive it is. You have to be almost extravagant to

attend.

* *

* * *

BD: All through

your career you’ve been a proponent of twentieth-century opera, of new works.

HR: Yes.

HR: Yes.

BD: Where is opera

going today?

HR: I wouldn’t

be a composer nowadays! I wouldn’t know where to go because on the

one hand if they get classical or neo-classical, if they get to this neo-veristic

or expressionistic style, they become imitators, and if they are too radical,

too much making scenic and musical experiences, they don’t get an audience.

In Europe sometimes, some opera houses can afford to bring operas they know

in advance that will not attract a crowd because in the budget they will compensate

with Aïda or La Bohème, or something like that.

Or in English-speaking opera houses they can go with Gilbert and Sullivan,

or with Lehár or Kálmán in Vienna. So one section

helps to finance the other, and that’s also a good principle which unfortunately

we don’t have in this country. If somebody was totally unknown and

who seems very weird for the audience, where do they get the money to produce

it? Sometimes the music publishers help a lot, and also in Europe the

radio and television stations help a lot in producing them. We did

a production of an opera by Ernest Krenek in Munich,

which was very avant-garde, called Die

Kaiserin. No theatre probably would have the courage to put

it into the repertoire. I know that Chicago did a lot of new things.

They did the world premiere of The Love

of Three Oranges by Prokofiev.

BD: That goes back

to the early ’20s, yes.

HR: Yes, but we

were very courageous then, and sometimes some opera houses get that reputation

to be the helpers for these young composers. Then they get an audience

internationally interested in all their world premieres. For example,

when I was Zurich, there was the world première of Lulu by Alban Berg. There was Mathis der Mahler of Hindemith.

In the mid-century they even had performances of Busoni operas which were

absolutely weird in the beginning of the century. So that stage got

a reputation of being an avant-garde theater, and they have their visibility

much more extended than it would be locally because the critics came and

there were reviews all over. Even in the score it’s written World Premiere

there on that date. There’s interchange of commercialism and of promoting

contemporary opera, and I think it’s a good thing because one helps the other.

BD: What advice

do you have for a young composer who wants to write opera today?

HR: In Europe there

are some of these composers who have the support of their publishers.

For example, Schott is very active there, as is Universal Edition UE in Vienna.

They need to promote new operas because when they print them, it’s not only

performed but all the libraries all over the world buy the score and put

on their shelves.

BD: But then do

they get done or do they just sit on the shelf?

HR: If an opera

is good, it prevails, don’t you think so?

BD: Well, I hope

so. Should opera be done in translation?

HR: That’s good

point. Yes and no! Yes, because it’s more accessible to be understood

by the audience, and no because the vowel which was used by the composer

to make the voice growing is a little bit betrayed. But I think for

certain operas, especially where there is a lot of fast recitatives and it’s

absolutely impossible to follow and to understand what’s going on, it’s better

to give it in a good translation. Now there’s a system of projection

of titles in the theater.

BD: Do you like

this idea.

HR: Yes, why not?

It’s better because it’s a compromise. It’s helping the acoustical

genuine-ness of producing the opera, and to make it understood! On

the other hand, if there’s too many words, then you really have to read and

you’re too much distracted. But I think they do a good job now.

You have it in Chicago as well?

BD: Yes, we’ve

had it the last couple of years.

HR: And you also

have it in Toronto. I would support it basically.

* *

* * *

BD: Let me ask

about a couple more roles that you have recorded. Tell me about Golaud.

What kind of a man is he?

HR: Golaud is a very tormented man. On one

side he’s deeply in love with Mélisande, but he’s old and he competes

naturally with the younger and more attractive brother, Pelléas.

He’s also a little bit quick in temper and that’s the reason why he kills

his brother. He’s devastated about his activity. It’s a very interesting

role, very, very interesting. It is very difficult to bring out the

drama of that man. He’s very suspicious all the time. You see

the grandiose scene when he holds his son Yniold to check whether something

is going on in the bedroom upstairs. That’s really great, but it’s

very difficult to bring out the drama because he’s not a bad man, he’s just

tormented. He cannot cope with his desire to kill his brother because

he almost killed him already when they go to the grotto. He almost

pushed him down, and he said, “I cannot do that.” But then his jealousy

gets so strong that it’s beyond his control, and he kills his brother.

Also he wants to know whose child Mélisande is carrying.

HR: Golaud is a very tormented man. On one

side he’s deeply in love with Mélisande, but he’s old and he competes

naturally with the younger and more attractive brother, Pelléas.

He’s also a little bit quick in temper and that’s the reason why he kills

his brother. He’s devastated about his activity. It’s a very interesting

role, very, very interesting. It is very difficult to bring out the

drama of that man. He’s very suspicious all the time. You see

the grandiose scene when he holds his son Yniold to check whether something

is going on in the bedroom upstairs. That’s really great, but it’s

very difficult to bring out the drama because he’s not a bad man, he’s just

tormented. He cannot cope with his desire to kill his brother because

he almost killed him already when they go to the grotto. He almost

pushed him down, and he said, “I cannot do that.” But then his jealousy

gets so strong that it’s beyond his control, and he kills his brother.

Also he wants to know whose child Mélisande is carrying.

BD: Whose child

is it? Is there an answer?

HR: I don’t know.

I don’t know whether Pelléas and Mélisande were platonic.

I think it was a kind of platonic relationship.

BD: So then the

child would be Golaud’s!

HR: I think so,

but he has doubts about it. You should ask Maerterlinck what he meant!

[Both laugh] But I think probably it’s his child because probably with

Pelléas it was platonic more than erotic. I also don’t feel

in the music that Debussy thought it was really erotic compulsion which put

them together. Mélisande is half a child, so she doesn’t know

what’s happening to her. Some stagings are very realistic, and others

are more esoteric according to the trans-lucidity of Debussy’s music.

It is not totally realistic in the real world. It comes out with the

sets and with the handling of the orchestration. If you play it energetically,

it comes out very, very strong, very Wagnerian. It was a hate-love

of Debussy of Wagner. He wanted to prove that Wagner was wrong.

He was caught in his hate-love, yet some passages sound exactly like Parsifal. They are literally in

the same key, so that is the problem.

BD: Pelléas

then, is one of the great masterworks?

HR: Oh certainly.

I’m not a musicologist, but I think that in the first part of this century

there are only three great innovations in music — Pelléas, Wozzeck, and an opera from a composer

who didn’t write a lot of opera but he innovated, that’s Bluebeard’s Castle by Bartók.

It’s a short opera, as you know, but very special. These are the three

more radical innovations at the beginning of this century.

BD: Did you ever

sing Bluebeard?

HR: Oh, yes, very

often.

BD: On the stage

or in concert?

HR: On stage and

even for television, and in several languages, but not in Hungarian!

I didn’t dare. I sang it in German, in French and in Italian.

The production we did for the Belgian Radio a long time ago —

at least thirty years — was quite interesting,

and it went on all over Europe for a while.

BD: If that’s being

done in the opera house, what else should be done on the bill that evening?

HR: Sometimes we

did Falla’s Maese Pedro, the puppet

play, or we did L’Heure Espagnole,

or even L’Enfant et Les Sortilèges.

BD: Do the two

Ravel operas work well together as an evening?

HR: It’s a possibility,

sure. Sometimes we did it also with Oedipus Rex, and there were nother combinations

we had. Whey did it once with Le

Roi David of Honegger, and even with Jeanne D’Arc au Bûcher, the other

Honegger. There should be a contrast because the Bartók opera

is very gloomy and very mysterious. It’s almost a written philosophy

of doom, so you must have a contrast to that, something lively.

BD: What advice

do you have for the young singer today?

HR: Study; be serious

about what you want to do; be patient; don’t ride too far out too soon; let

your personality and your voice mature, and observe what your forerunners

did and continue the tradition.

BD: Are you optimistic

about the future of opera?

HR: Oh, certainly,

certainly. There are excellent talents around, beautiful voices, and

there is a kind of renaissance of opera going on. Talking now about

the availability of young hopefuls — naturally, if

you teach a lot of students because you have to have a full load

— not all of them will make a career. But there’s always

one or two per generation in every town who are ready to be promoted to get

the possibility to show their potential.

BD: As you approach

your 70th birthday, is there any one thing that stands out in your mind as

being surprising that you never thought would happen?

HR: I don’t believe that I’m 70!

I don’t feel like that. But the calendar says it so, and I have to

believe it. Also in the state of New York, at 70 you have mandatory

retirement, so I will retire in June and take it a bit easy. I may

do some lectures. I’ve been invited by several of the universities

to do some lectures or give a master-course. I also have a lot of notes

which have accumulated during all these years, and maybe I’ll put them together

and they may come out with a little brochure. But there are so many

already around that you must be very careful not to duplicate what others

said already... and maybe better than you can do it. But if you are

very sincere and you honestly try to explain what were the problems during

your long career, it may be helpful for young people. So I plan to

do that.

HR: I don’t believe that I’m 70!

I don’t feel like that. But the calendar says it so, and I have to

believe it. Also in the state of New York, at 70 you have mandatory

retirement, so I will retire in June and take it a bit easy. I may

do some lectures. I’ve been invited by several of the universities

to do some lectures or give a master-course. I also have a lot of notes

which have accumulated during all these years, and maybe I’ll put them together

and they may come out with a little brochure. But there are so many

already around that you must be very careful not to duplicate what others

said already... and maybe better than you can do it. But if you are

very sincere and you honestly try to explain what were the problems during

your long career, it may be helpful for young people. So I plan to

do that.

BD: I look forward

to that very much. I meant to ask you, did you ever sing here in Chicago?

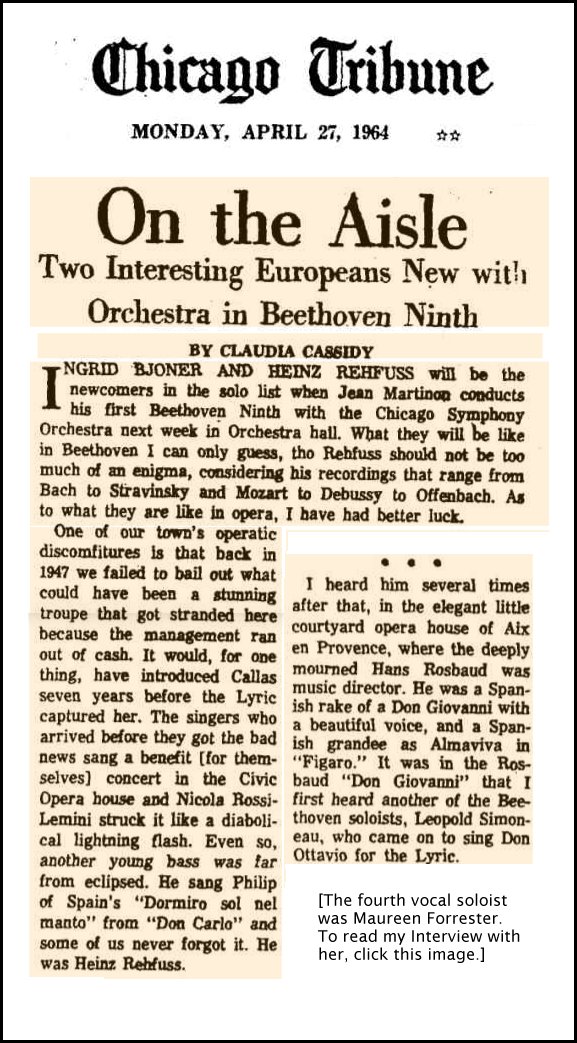

HR: I was there

once with a company, just after the War, but unfortunately there was a lot

of intrigues. There was somebody who was supposed to back the whole

thing with money, and he withdrew because he got political aspects.

Some of the singers were thought to be ex-Nazi or ex-Fascist, or something

like that, which was not true. So it was a little bit tug of war between

local artists, who were a little bit worried and displeased that new people

were imported from Europe. So we had to interrupt the season.

I think it was in early ’47. Can you imagine, forty years ago!

I cannot believe it. It was a big experience because at the end of

the season we did Turandot, and

I was also cast to do Athanaël in Thaïs

by Massenet. It was supposed to be a good season. There were

good people there. There was [Marjorie] Lawrence, the two Konetzni sisters

[Hilde and Anny], [Salvatore] Baccaloni, Ebe Stignani, all people who were

very important at that time.

BD: And it all

fell apart?

HR: They were all

stranded there, so we sailed home after three weeks.

BD: I’m so sorry

that happened to you here.

HR: No, I still

keep a good memory of that time. I was at the very beginning of my

career.

BD: Did you sing

any other Massenet besides Athanaël?

HR: Yes, on radio

I sang Don Quichotte in a concert version. It has some very, very good

moments. If you have a strong personality for Don Quichotte, I think

it’s worth doing it. It was written, if I’m correct, for Chaliapin,

and there was André Pernet in Paris. He was famous for the part,

as was Vanni Marcoux. There’s a recording of him, which is very impressive.

BD: In a couple

of seasons [1913-14 and 1929-30] we had Vanni Marcoux as Don Quichotte (among

other roles) here in Chicago. [See my article Massenet, Mary Garden, and the Chicago Opera

1910-1932.]

HR: Oh, really?

But you’re not that old that you could see that!

BD: Oh, no, no,

no! I see it in the history books.

HR: That was, by

the way, a very good interpretation of the work. It’s too bad that

Ravel didn’t write the whole Don Quichotte.

His three songs for Don Quichotte are so really genuinely Spanish because

he was not only the elegant Frenchman, but by his parents he was also half-Spaniard.

So he would have written a great Don Quichotte

probably. When he wrote his piece, it was for the film, and he didn’t

even make it. It was Jacques Ibert who was accepted. He won the

competition, and his music was used in the movie.

BD: Tell me about

Athanaël.

HR: It’s kind of

popular in French-speaking sections. I did one performance in Geneva,

and we did one in Strasbourg, which is a very good opera house because they

have the technical possibilities of a German opera house because it was built

by Siemens. So it was one of the best stages in France. Naturally

now, everything has improved enormously. We’re talking about the ’50s

and early ’60s. But now most of the opera

houses in France have got a very good technical equipment. Some were

very, very not up to the technical things, because there was no money after

the War. But things are better and they have done a great job.

BD: Thank you so

much for being a singer! This has been a fascinating hour talking to

you.

HR: Oh, thank you

so much. Thank you for your interest.

© 1987 Bruce Duffie

This conversation was recorded on the telephone on April 26, 1987.

Portions were broadcast on WNIB the following month, and again in 1992 and

1997. This transcription was made in 2014, and posted on this website

at that time. My thanks to British soprano

Una Barry

for her help in preparing this website presentation.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed

and posted on this website,

click here. To read

my thoughts on editing these interviews for print, as well as a few other

interesting observations, click

here.

* * * *

*

Award -

winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie

was with WNIB,

Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975

until its final moment as a classical station in

February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared

in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he

now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM, as

well as on Contemporary

Classical Internet Radio.

You are invited to visit his website for more information

about his work, including selected transcripts

of other interviews, plus a full list of his

guests. He would also like to call your attention

to the photos and information about his grandfather,

who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago.

You may also send him E-Mail with comments,

questions and suggestions.

BD: You’re teaching both singing and stage acting?

BD: You’re teaching both singing and stage acting? BD: Is that a good thing?

BD: Is that a good thing? HR: Oh yes. I did Don Giovanni, I did the

Count, and in the ’50s I was the Don Giovanni at the

Aix-en-Provence Festival. I did recording of it and also Le Nozze di Figaro. That was at

a time when Rosbaud was taking over, and he was an excellent Mozart interpreter.

HR: Oh yes. I did Don Giovanni, I did the

Count, and in the ’50s I was the Don Giovanni at the

Aix-en-Provence Festival. I did recording of it and also Le Nozze di Figaro. That was at

a time when Rosbaud was taking over, and he was an excellent Mozart interpreter.

HR: Yes.

HR: Yes. HR: Golaud is a very tormented man. On one

side he’s deeply in love with Mélisande, but he’s old and he competes

naturally with the younger and more attractive brother, Pelléas.

He’s also a little bit quick in temper and that’s the reason why he kills

his brother. He’s devastated about his activity. It’s a very interesting

role, very, very interesting. It is very difficult to bring out the

drama of that man. He’s very suspicious all the time. You see

the grandiose scene when he holds his son Yniold to check whether something

is going on in the bedroom upstairs. That’s really great, but it’s

very difficult to bring out the drama because he’s not a bad man, he’s just

tormented. He cannot cope with his desire to kill his brother because

he almost killed him already when they go to the grotto. He almost

pushed him down, and he said, “I cannot do that.” But then his jealousy

gets so strong that it’s beyond his control, and he kills his brother.

Also he wants to know whose child Mélisande is carrying.

HR: Golaud is a very tormented man. On one

side he’s deeply in love with Mélisande, but he’s old and he competes

naturally with the younger and more attractive brother, Pelléas.

He’s also a little bit quick in temper and that’s the reason why he kills

his brother. He’s devastated about his activity. It’s a very interesting

role, very, very interesting. It is very difficult to bring out the

drama of that man. He’s very suspicious all the time. You see

the grandiose scene when he holds his son Yniold to check whether something

is going on in the bedroom upstairs. That’s really great, but it’s

very difficult to bring out the drama because he’s not a bad man, he’s just

tormented. He cannot cope with his desire to kill his brother because

he almost killed him already when they go to the grotto. He almost

pushed him down, and he said, “I cannot do that.” But then his jealousy

gets so strong that it’s beyond his control, and he kills his brother.

Also he wants to know whose child Mélisande is carrying.

HR: I don’t believe that I’m 70!

I don’t feel like that. But the calendar says it so, and I have to

believe it. Also in the state of New York, at 70 you have mandatory

retirement, so I will retire in June and take it a bit easy. I may

do some lectures. I’ve been invited by several of the universities

to do some lectures or give a master-course. I also have a lot of notes

which have accumulated during all these years, and maybe I’ll put them together

and they may come out with a little brochure. But there are so many

already around that you must be very careful not to duplicate what others

said already... and maybe better than you can do it. But if you are

very sincere and you honestly try to explain what were the problems during

your long career, it may be helpful for young people. So I plan to

do that.

HR: I don’t believe that I’m 70!

I don’t feel like that. But the calendar says it so, and I have to

believe it. Also in the state of New York, at 70 you have mandatory

retirement, so I will retire in June and take it a bit easy. I may

do some lectures. I’ve been invited by several of the universities

to do some lectures or give a master-course. I also have a lot of notes

which have accumulated during all these years, and maybe I’ll put them together

and they may come out with a little brochure. But there are so many

already around that you must be very careful not to duplicate what others

said already... and maybe better than you can do it. But if you are

very sincere and you honestly try to explain what were the problems during

your long career, it may be helpful for young people. So I plan to

do that.