|

Blanche Thebom: Mezzo-soprano lauded for

her interpretations of Wagner

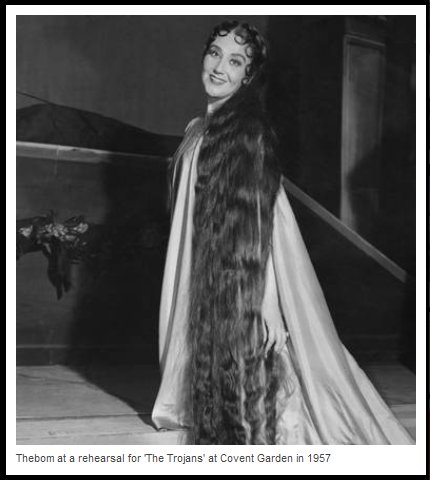

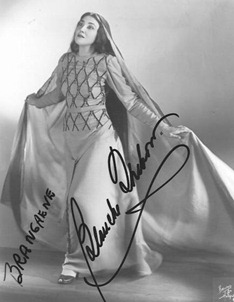

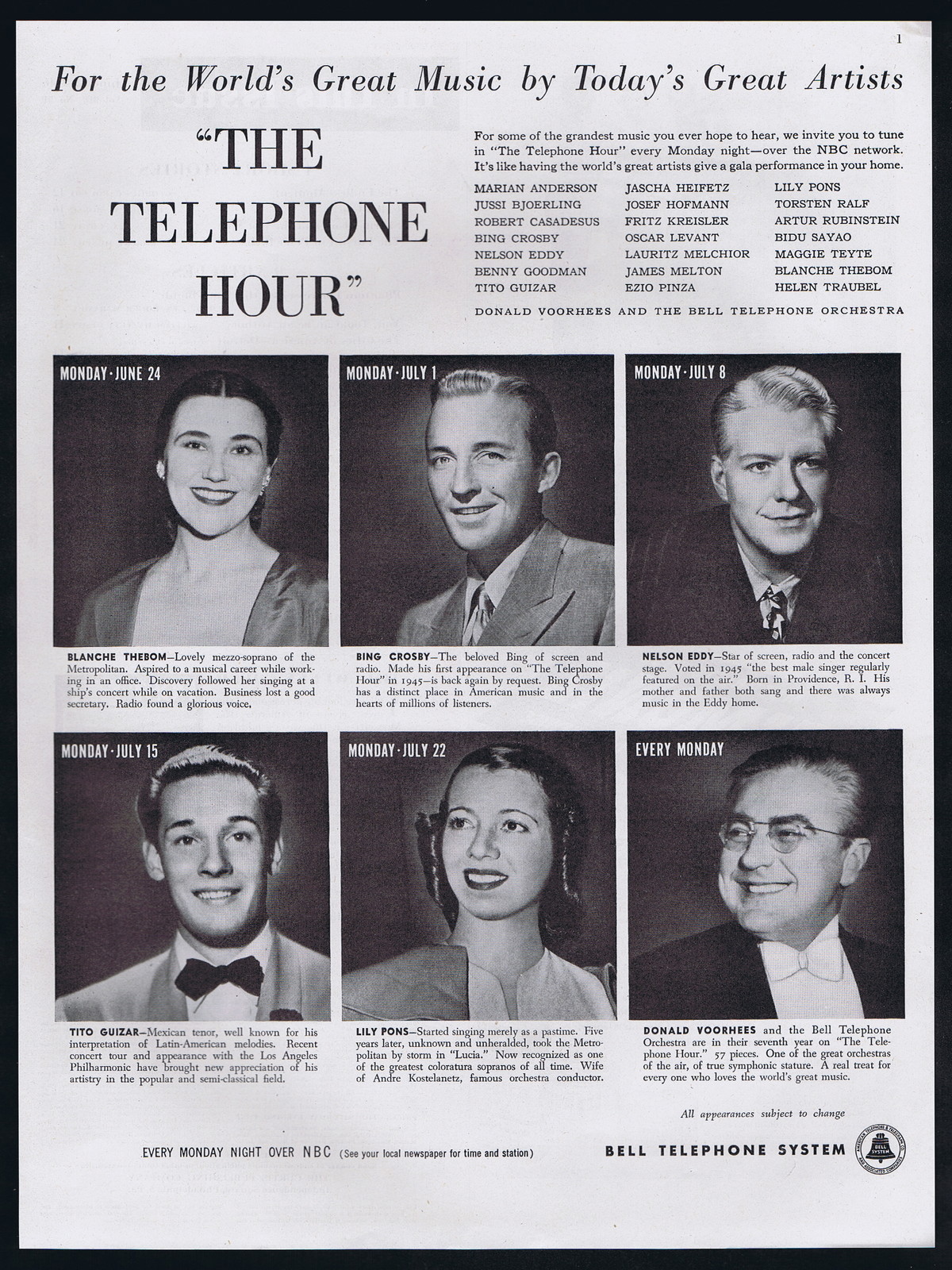

By Elizabeth Forbes The Independent, 30 April 2010  The American mezzo-soprano Blanche Thebom was not only a

fine singer with a lovely voice, she was also a very beautiful woman

with a superb figure and amazing hair that, when let down, hung well

below her knees. Though she sang mostly in the United States, appearing

at the Metropolitan, New York, for 22 seasons, as well as in Chicago,

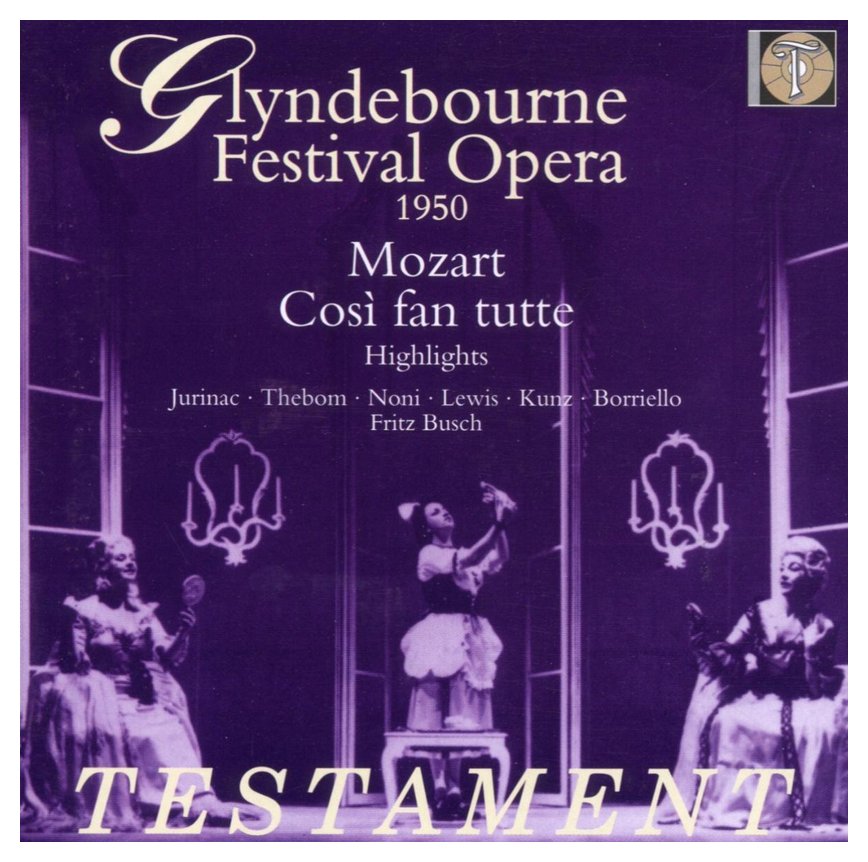

San Francisco, Dallas and other cities, she visited Glyndebourne in

1950 for an enchanting Dorabella in Mozart's Così fan tutte and Covent

Garden for Dido in the first professional stage performance in the UK

of Berlioz' Les Troyens in

1957. She excelled in the operas of Wagner, but her range was wide and

her repertory included roles by Gluck, Handel, Verdi, Richard and

Johann Strauss and Stravinsky. The American mezzo-soprano Blanche Thebom was not only a

fine singer with a lovely voice, she was also a very beautiful woman

with a superb figure and amazing hair that, when let down, hung well

below her knees. Though she sang mostly in the United States, appearing

at the Metropolitan, New York, for 22 seasons, as well as in Chicago,

San Francisco, Dallas and other cities, she visited Glyndebourne in

1950 for an enchanting Dorabella in Mozart's Così fan tutte and Covent

Garden for Dido in the first professional stage performance in the UK

of Berlioz' Les Troyens in

1957. She excelled in the operas of Wagner, but her range was wide and

her repertory included roles by Gluck, Handel, Verdi, Richard and

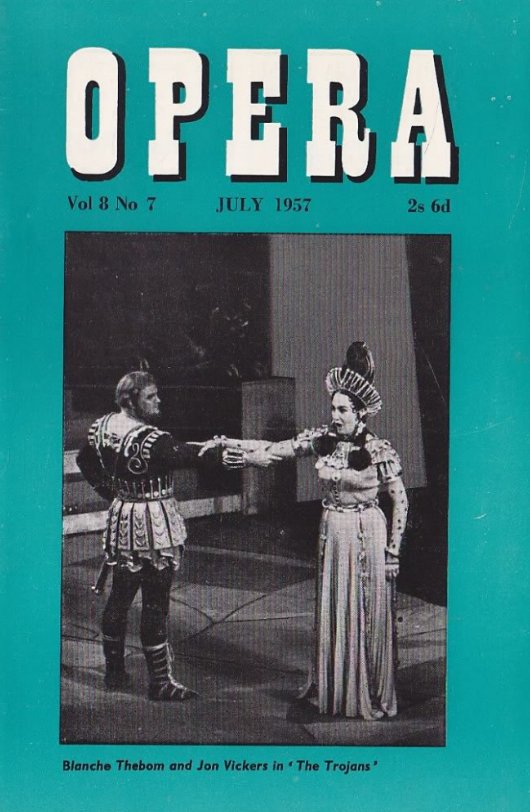

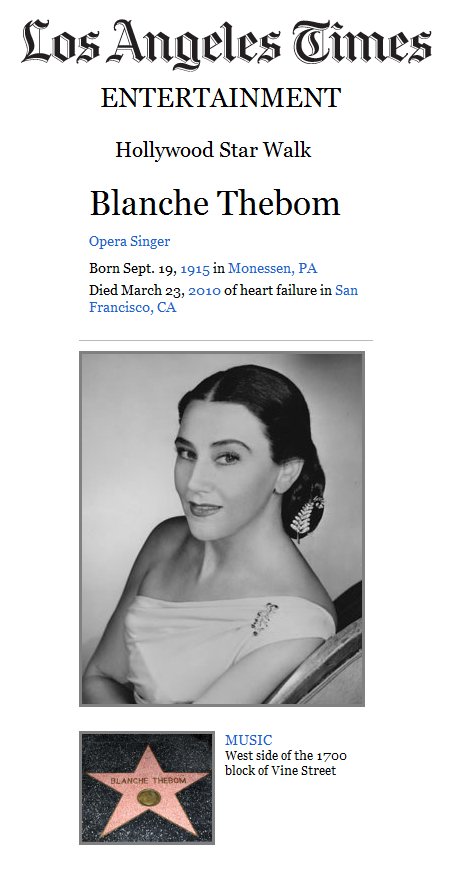

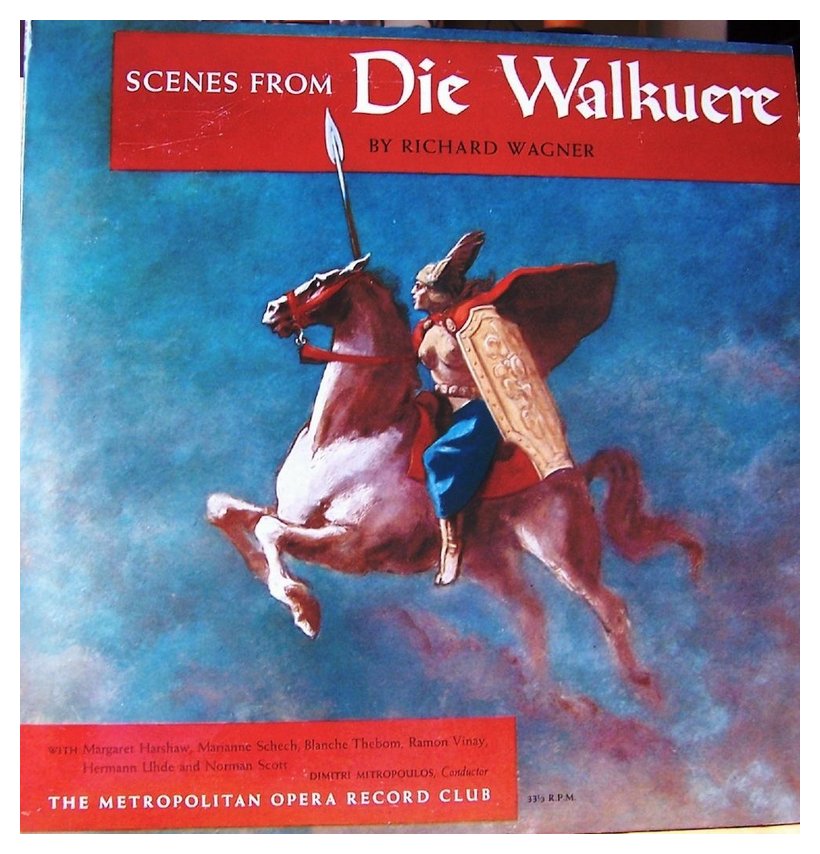

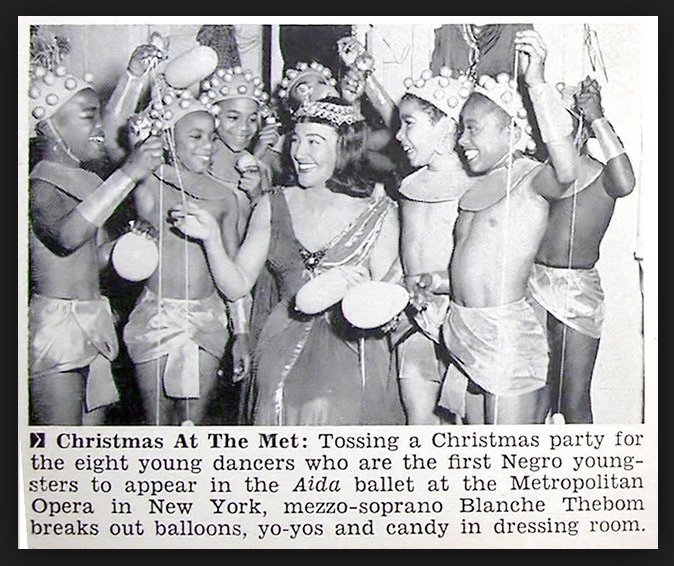

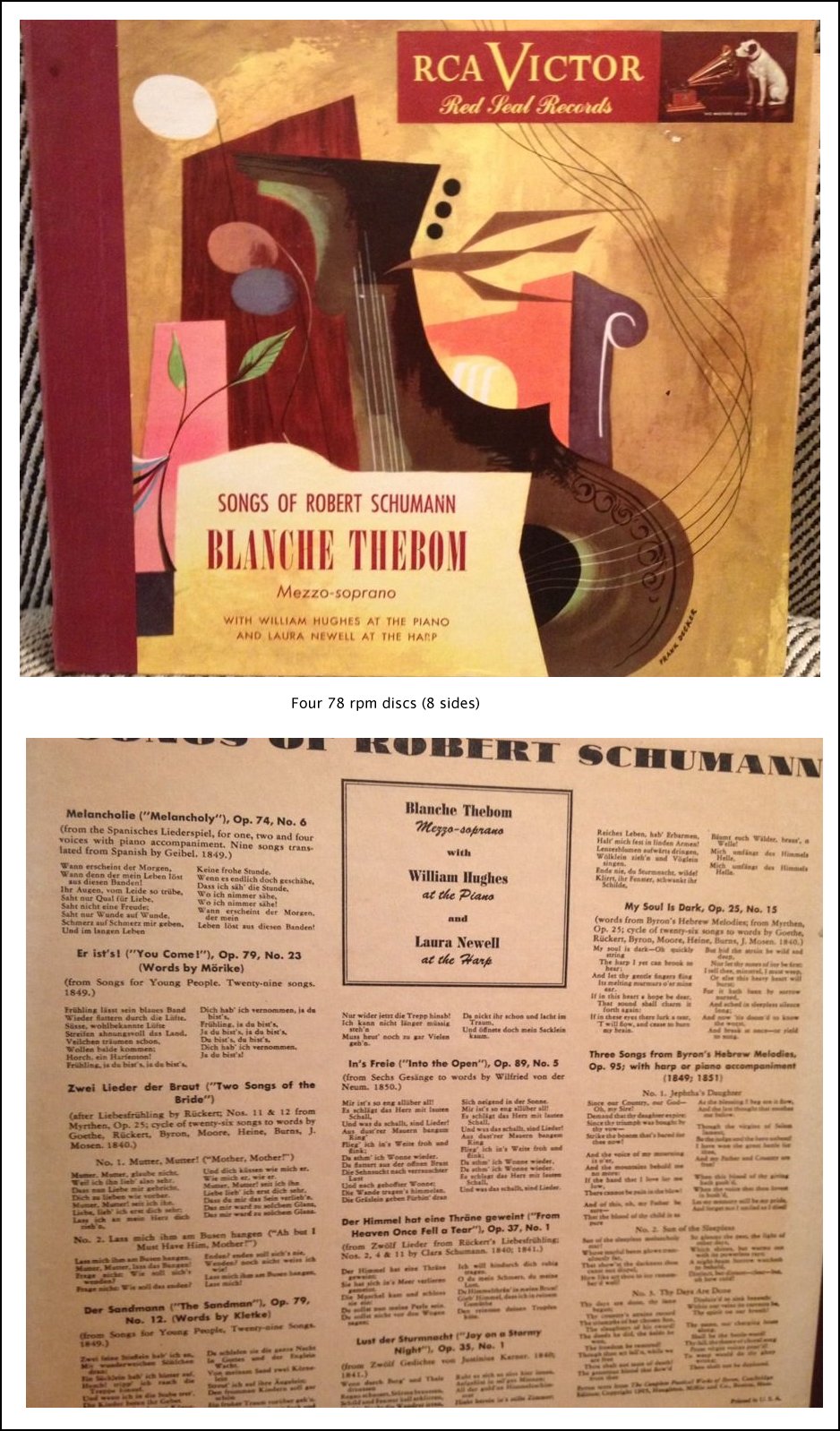

Johann Strauss and Stravinsky.Thebom was born in Monessen, Pennsylvania, in 1918. She studied in New York with Margaret Matzanauer and Edyth Walker, both famous singers in their day. She made her operatic debut in Philadelphia with the Metropolitan Opera Company as Brangäne in Tristan und Isolde on 28 November 1944 and repeated the role in New York on 14 December the same year. During her first season she also sang Fricka in both Das Rheingold and Die Walküre as well as Waltraute in Götterdämmerung. Her other Wagner roles at the Metropolitan included Venus in Tannhäuser and Ortrud in Lohengrin, but Brangäne remained her favourite; she sang it in Chicago in 1946, in San Francisco in 1947 and on the 1952 recording conducted by Wilhelm Furtwängler in which Kirsten Flagstad sings Isolde. Meanwhile Thebom enlarged her Metropolitan repertory with Laura in Ponchielli's La gioconda, Giulietta in Offenbach's Les Contes d'Hoffmann, Marina in Mussorgsky's Boris Godunov, Amneris in Verdi's Aïda, the title role of Thomas' Mignon, Delilah in Saint-Saëns' Samson et Dalila, Herodias in Richard Strauss's Salome and Prince Orlovsky in Johann Strauss's Die Fledermaus. In 1953 she sang Baba the Turk, the Bearded Lady, in the US premiere of Stravinksy's The Rake's Progress, scoring a personal triumph. Having made her San Francisco debut as Laura, she repeated many of her Metropolitan roles there, but also gained some interesting new ones, including Oktavian in Richard Strauss' Der Rosenkavalier, Mother Marie in Poulenc's Dialogues des Carmélites and Orfeo in Gluck's Orfeo ed Euridice. Her appearance as Dorabella at Glyndebourne in 1950 was a great success. Conducted by Fritz Busch and directed by Carl Ebert with Sena Jurinac as Fiordiligi, it was a particularly enjoyable performance of Così fan tutte in which the American visitor fitted perfectly. The first professional stage performances of The Trojans (the opera was sung in English) were even more memorable. Conducted by Rafael Kubelik, then music director of the Royal Opera and directed by John Gielgud, with Jon Vickers as Aeneas opposite Thebom's Dido, the production aroused enormous interest in operatic circles. The eight performances, opening on 6 June 1957, were all sold out, with people coming from all over Europe and even further afield. Thebom sang the love music most beautifully, and if she could not quite express the outrage of the abandoned queen after the departure of Aeneas, she looked magnificent in her death scene at the end, the famous hair falling like a curtain around her. There were five more performances of The Trojans at Covent Garden in the autumn 1958.  Thebom continued singing at the Metropolitan until the 1966-67 season, then became general manager of the short-lived Atlanta Opera Company in 1968. Later she retired to San Francisco. Blanche Thebom, opera singer; born Monressen, Pennsylvania 19 September 1918; married Richard Metz; died San Francisco 23 March 2010. -- Note:

Names on this webpage which are links refer to my Interviews elsewhere

on this website. BD

|

Bruce Duffie:

Let's start out by talking a little bit about Wagner.

Bruce Duffie:

Let's start out by talking a little bit about Wagner. BT:

Yes. I did have an important recital in Minneapolis one

time. That's a real music-loving town with an astute audience,

and I was a young artist and I was eager to do a very good job.

Well there was a lady in the front row knitting on a wide scarf.

She was watching me and then she'd flip the thing over and continue to

knit. It got to the point where I was missing cues! You

wonder when she was going to flip next. So at the end of the

second group, I sent word out to the manager asking if he would please

be good enough to ask this lady to move a few rows back if she wanted

to continue to knit. I remember another time during an orchestral

rehearsal of Orfeo when

Markova was dancing the blessed spirit. Herbert Graf had done the

mise-en-scène, and it

was done with a scrim. Of course we all loathed the scrim, and

that makes side lighting imperative unless you are doing a special

effect, which was not the case during this particular dance. I

wasn't singing in that production, but was in the house because I

adored that lady because I had studied dance a bit just for physical

control. I never could have been a dancer, but I feel it is an

imperative adjunct to an opera singer's training. Not only the

body-movement, but the true plastique

and balance. Otherwise there is no elegance in movement.

Just body-movement doesn't do it for me. There isn't enough

discipline. So I always took ballet classes and was fascinated

with everything Markova did. She was a beautiful artist with

incredible timing. She was etherial, not like anything alive up

there. But anyway, in this rehearsal she would hesitate

occasionally and then pick it up a few steps later, and finally she

just stopped. She said she could not dance with the lighting that

way. She needed at least one spotlight from the front. She

said, "I must have something to dance into." [For more about the

point of view of the operatic dancer, see my Interview with Maria

Tallchief.] You must

have the ambiance for the dancer, and I

didn't realize this was important for them, too. It's the whole

passage of everything, the whole continuity and the flow of

communication. It isn't that you have to focus on something, but

whatever place you are performing you have to have awareness of the

area into which you are projecting. For us it is character

projection, style projection, vocal projection, dramatic projection,

everything goes at once. I was sitting with a colleague back

then, and we were delighted she had challenged the direction. We

thanked her for that. But in my early days, I never had the

misfortune to be straight-jacketed by "traditional" stances and so on.

BT:

Yes. I did have an important recital in Minneapolis one

time. That's a real music-loving town with an astute audience,

and I was a young artist and I was eager to do a very good job.

Well there was a lady in the front row knitting on a wide scarf.

She was watching me and then she'd flip the thing over and continue to

knit. It got to the point where I was missing cues! You

wonder when she was going to flip next. So at the end of the

second group, I sent word out to the manager asking if he would please

be good enough to ask this lady to move a few rows back if she wanted

to continue to knit. I remember another time during an orchestral

rehearsal of Orfeo when

Markova was dancing the blessed spirit. Herbert Graf had done the

mise-en-scène, and it

was done with a scrim. Of course we all loathed the scrim, and

that makes side lighting imperative unless you are doing a special

effect, which was not the case during this particular dance. I

wasn't singing in that production, but was in the house because I

adored that lady because I had studied dance a bit just for physical

control. I never could have been a dancer, but I feel it is an

imperative adjunct to an opera singer's training. Not only the

body-movement, but the true plastique

and balance. Otherwise there is no elegance in movement.

Just body-movement doesn't do it for me. There isn't enough

discipline. So I always took ballet classes and was fascinated

with everything Markova did. She was a beautiful artist with

incredible timing. She was etherial, not like anything alive up

there. But anyway, in this rehearsal she would hesitate

occasionally and then pick it up a few steps later, and finally she

just stopped. She said she could not dance with the lighting that

way. She needed at least one spotlight from the front. She

said, "I must have something to dance into." [For more about the

point of view of the operatic dancer, see my Interview with Maria

Tallchief.] You must

have the ambiance for the dancer, and I

didn't realize this was important for them, too. It's the whole

passage of everything, the whole continuity and the flow of

communication. It isn't that you have to focus on something, but

whatever place you are performing you have to have awareness of the

area into which you are projecting. For us it is character

projection, style projection, vocal projection, dramatic projection,

everything goes at once. I was sitting with a colleague back

then, and we were delighted she had challenged the direction. We

thanked her for that. But in my early days, I never had the

misfortune to be straight-jacketed by "traditional" stances and so on. BT: I never

did it that way. I played it through a long series of emotional

motivations. First is the silence, sort of "Good God, what have I

done?" I never looked at them after giving them the drink.

I went back to the table with my back toward them. There were no

cries of pain which would have been the effect of the poison. The

music, though, makes you feel how the drink penetrates every fiber of

their beings, so I worked my character into this also with a shuddering

kind of apprehension and excitement. That's the dance

training. When the music says something, there has to be a

physical response as well. Then I went through a series of

increased tensions until the first word was sung. Then there was

a joy and delight at knowing they were not dead. That's the first

real proof that they are still alive. Because my back was toward

them, my last vision of them had been their intense antagonism, like

two opponents in combat, and when I turned to see them looking with

such love, I don't think Brangäne quite understands until they

fall in one another's arms, which happens exactly at the first

announcement of the arrival of Marke. So it's some marvelous

moments for acting. I've seen recent productions where the

stage-director has gotten Brangäne off the stage and it indicated

to me that he has no concept of what to do with those wonderful

passages.

BT: I never

did it that way. I played it through a long series of emotional

motivations. First is the silence, sort of "Good God, what have I

done?" I never looked at them after giving them the drink.

I went back to the table with my back toward them. There were no

cries of pain which would have been the effect of the poison. The

music, though, makes you feel how the drink penetrates every fiber of

their beings, so I worked my character into this also with a shuddering

kind of apprehension and excitement. That's the dance

training. When the music says something, there has to be a

physical response as well. Then I went through a series of

increased tensions until the first word was sung. Then there was

a joy and delight at knowing they were not dead. That's the first

real proof that they are still alive. Because my back was toward

them, my last vision of them had been their intense antagonism, like

two opponents in combat, and when I turned to see them looking with

such love, I don't think Brangäne quite understands until they

fall in one another's arms, which happens exactly at the first

announcement of the arrival of Marke. So it's some marvelous

moments for acting. I've seen recent productions where the

stage-director has gotten Brangäne off the stage and it indicated

to me that he has no concept of what to do with those wonderful

passages.

BT: Yes, I think

so. It depends on how you approach things. Some of the

greatest personal involvement that I have ever undergone — research and

thinking and listening and trying to hang it all together — was with

Gluck's Orfeo, which is

basically a very simple score. So it's not the complexity of the

music. There's a lot of contemporary music that if you can just

manage to make the intervals and hit the right notes and do them in

time, that's really all you have to do. The structure is almost

total without you. In Wagner, the fact that he was his own

librettist makes the words incredibly important. I quote Wagner's

music in very early session in classes for students who are trying to

learn how to go about studying. Most people don't know how to

study; they don't know what they're looking for or how to begin.

It comes as a thundering surprise that every opera and every song

started as a text that created the mood, that created the story that

fascinated the composer. The music that comes to a gifted

composer, then, is a just a setting of the words. That's all it

is. The emotional impacts are engendered through the words and

dramatic situations that are built as a result of that. Because

Wagner wrote his own texts, there is more closeness with his

music. You find alliterations in the things that he does that fit

exactly the music that must have been going through his head as the

words came to him. One exercise I have students do is to take the

vocal line out — have an accompanist or if they can do it themselves —

and simply concentrate on what there is in the musical structure.

The opera singer is guilty many too many times of not knowing what is

happening in there. Each singer should know not only what he or

she is singing but what's going on around in the music. We are

the tip of the iceberg, and so much of what one needs to know for

interpretation is reflected in how the composer has set the

music. You need to know what the lines mean, or what the composer

meant when he sat with his text and mentally saw his stage. You

don't need "wing" it or be confused about what the composer meant

because it is all there if the singers would take the trouble to dig it

out and see how their line fits into the whole. It's the person

who only knows his own lines who will be dead during other

passages. They simply don't feel themselves as a part of the

whole fabric — if they even know what the fabric is. As far as

Wagner is specifically concerned, I don't feel there is ever a time or

a person who can ever say that he or she knows everything that is

there. If I were to sing a performance of Brangäne tomorrow

night, I'm sure that in studying it again between now and then I'd find

things on the first two pages that I never saw before. It's just

limitless.

BT: Yes, I think

so. It depends on how you approach things. Some of the

greatest personal involvement that I have ever undergone — research and

thinking and listening and trying to hang it all together — was with

Gluck's Orfeo, which is

basically a very simple score. So it's not the complexity of the

music. There's a lot of contemporary music that if you can just

manage to make the intervals and hit the right notes and do them in

time, that's really all you have to do. The structure is almost

total without you. In Wagner, the fact that he was his own

librettist makes the words incredibly important. I quote Wagner's

music in very early session in classes for students who are trying to

learn how to go about studying. Most people don't know how to

study; they don't know what they're looking for or how to begin.

It comes as a thundering surprise that every opera and every song

started as a text that created the mood, that created the story that

fascinated the composer. The music that comes to a gifted

composer, then, is a just a setting of the words. That's all it

is. The emotional impacts are engendered through the words and

dramatic situations that are built as a result of that. Because

Wagner wrote his own texts, there is more closeness with his

music. You find alliterations in the things that he does that fit

exactly the music that must have been going through his head as the

words came to him. One exercise I have students do is to take the

vocal line out — have an accompanist or if they can do it themselves —

and simply concentrate on what there is in the musical structure.

The opera singer is guilty many too many times of not knowing what is

happening in there. Each singer should know not only what he or

she is singing but what's going on around in the music. We are

the tip of the iceberg, and so much of what one needs to know for

interpretation is reflected in how the composer has set the

music. You need to know what the lines mean, or what the composer

meant when he sat with his text and mentally saw his stage. You

don't need "wing" it or be confused about what the composer meant

because it is all there if the singers would take the trouble to dig it

out and see how their line fits into the whole. It's the person

who only knows his own lines who will be dead during other

passages. They simply don't feel themselves as a part of the

whole fabric — if they even know what the fabric is. As far as

Wagner is specifically concerned, I don't feel there is ever a time or

a person who can ever say that he or she knows everything that is

there. If I were to sing a performance of Brangäne tomorrow

night, I'm sure that in studying it again between now and then I'd find

things on the first two pages that I never saw before. It's just

limitless.

BD: Is Wotan

a God or a man?

BD: Is Wotan

a God or a man?| Blanche Thebom, Star at the Met and Beyond,

Dies at 94

By MARGALIT FOX Published: March 27, 2010, The New York Times [Text only - photos from another source] Blanche Thebom, a mezzo-soprano who was discovered singing in a shipboard lounge as a teenager and went on to sing more than 350 performances with the Metropolitan Opera, died on Tuesday at her home in San Francisco. She was 94. Her death was confirmed by Roger Greenberg, a longtime friend. In a field long dominated by Europeans, Ms. Thebom (pronounced THEE-bom, with the th as in thin) was part of the first, midcentury wave of American opera singers to attain international careers. Associated with the Met from the mid-1940s to the mid-1960s, she was praised by critics for her warm voice, attentive phrasing and sensitive acting. Ms. Thebom was best known for Wagner. She made her Metropolitan Opera debut in Philadelphia in November 1944 as Brangäne in an out-of-town production of “Tristan und Isolde”; the next month she appeared with the company in New York, singing Fricka in “Die Walküre.” Reviewing her “Walküre,” a critic for The New York Times wrote that Ms. Thebom “scored an immediate success.” At the Met, her other roles included Ortrud in Wagner’s “Lohengrin,” Azucena in Verdi’s “Trovatore” and Amneris in his “Aïda,” and the title role in Bizet’s “Carmen.” She also sang at Covent Garden and the Glyndebourne festival in England. In 1957, presented by the impresario Sol Hurok, Ms. Thebom made a three-week tour of the Soviet Union. (There, as The Times wrote afterward, “the singer was surprised to find that her mink coat was a traffic stopper wherever she went.”) Her engagements included a Carmen with the Bolshoi Opera in Moscow. Ms. Thebom last performed at the Met in 1967. She later directed the opera program at the University of Arkansas, Little Rock, and afterward moved to San Francisco, where she taught privately and helped create a training program for young singers. In later years, Ms. Thebom appeared often in duo recitals with the soprano Eleanor Steber.  Blanche Thebom was born on Sept. 19, 1915, in Monessen, Pa., and reared in Canton, Ohio; the year of her birth is often given erroneously as 1918. Her parents immigrated from Sweden. As a girl, she sang in a church choir. While still a teenager, Ms. Thebom traveled to Sweden with her parents in the 1930s. On the crossing, she was heard singing in the ship’s lounge by Kosti Vehanen, a pianist who often accompanied the contralto Marian Anderson. Mr. Vehanen arranged for Blanche to study in New York, where her primary teacher was Edyth Walker, a former Metropolitan Opera mezzo. Ms. Thebom’s marriage, to Richard Metz, ended in divorce. No immediate family members survive. Her recordings include Mozart’s “Così Fan Tutte,” in which she sings Dorabella [shown below], on the Sony Classical label, and albums of songs by Hugo Wolf and Robert Schumann [also shown below] for RCA Victor. She appeared in films, among them “Irish Eyes Are Smiling” (1944) and “The Great Caruso” (1951). Ms. Thebom’s career seemed ordained from the moment she stepped onto the New York stage. Making her recital debut at Town Hall in January 1944, she sang a program of Massenet, Handel, Mussorgsky and Brahms. Reviewing the concert, The Times called her a “richly gifted young artist,” adding, “Her work revealed a wealth of temperament and an inherent musicianship that presage a brilliant career.”   [The following is from a review

in Gramophone Magazine (June,

1994) by Alan Blyth]

These highlights, which I refer to in my Glyndebourne collection (see page 38), have often been held up as a model of how the piece should be performed, and countless have been the laments that EMI did not throw caution to the winds and record the work complete. At least they preserve the better part of Jurinac's sovereign Fiordiligi, not recorded elsewhere, thus making it a 'must' for the many lovers of her singing. Here her voice was youthfully fresh, although not quite as full and rounded as it was to become. The ease and warmth of delivery, the natural quality of tone were prized by all who heard her in the part, an apt concomitant to her beguiling presence. Hers isn't quite the commanding Fiordiligi of her predecessor and successor in the role—Souez and Vaness—in Glyndebourne recordings on disc, but a more vulnerable and lovable creature. She is aptly partnered in the duets by the lively though not particularly individual Dorabella of Thebom and the mellifluous Ferrando of Richard Lewis, then at the beginning of a 24-year stint in the house. Erich Kunz was an engaging and mellow-voiced Guglielmo—what a pity his arias weren't included at the sessions—who contributes positively to the perfect ensemble of the two quintets and sings seductively to Thebom's Dorabella in ''Il core vi dono''. Boriello brings an Italianate tang to Alfonso's contributions. For some reason the producer David Bicknell took a dislike to Noni's equally Italianate Despina, so her arias were at the time excluded. However, a few months later he had relented and she recorded both for HMV (DA1986, 7/51—nla) but not with Busch conducting. These are included here in the right order. Busch's interpretation differs little from that on his 1935 set (Pearl, 3/91) and remains a model of how to marry incisive and vital accents with the yielding phrase. The RPO, with Brain playing the horn obbligato in ''Per pieta'', perform ingratiatingly. The recording, made on early tape, has some print-through, but on the new transfer it is seldom bothersome. Testament have come up with some additional material: rehearsal takes for ''Prendero quel brunettino'', ''Per pieta'' (during which, at one point Jurinac breaks down, and, endearingly, curses herself) and ''Fra gli amplessi'', the last marginally freer than the published performance. Busch can be heard a couple of times encouraging his players. Now we must have the roughly contemporaneous extracts from Idomeneo.     |

© 1982 Bruce Duffie

This interview was recorded at her apartment in Chicago on

October 19, 1982. Segments were used (with recordings)

on WNIB in 1986 and 1993. The

transcription was made and published in Wagner News in August, 1983.

It was re-editied and posted on this

website in 2013.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website, click here.

Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM, as well as on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio.

You are invited to visit his website for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.