|

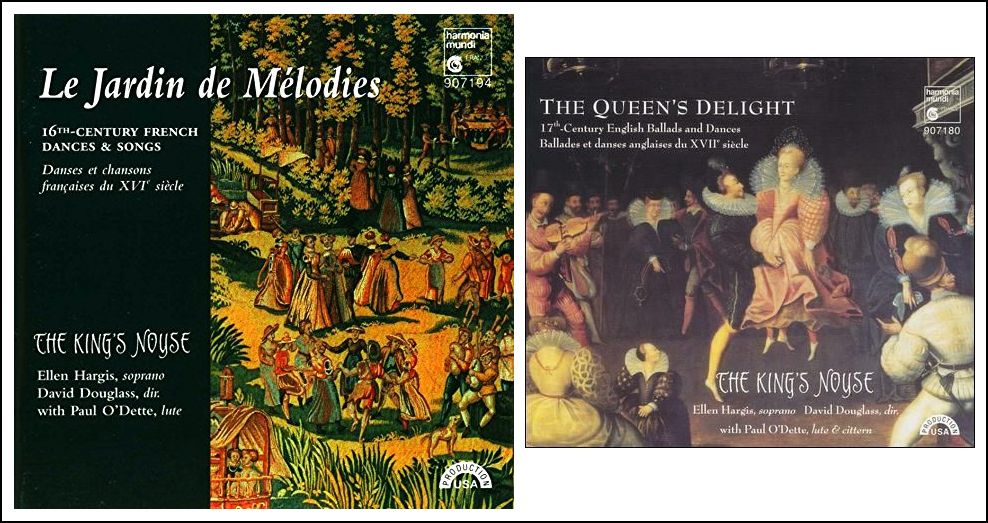

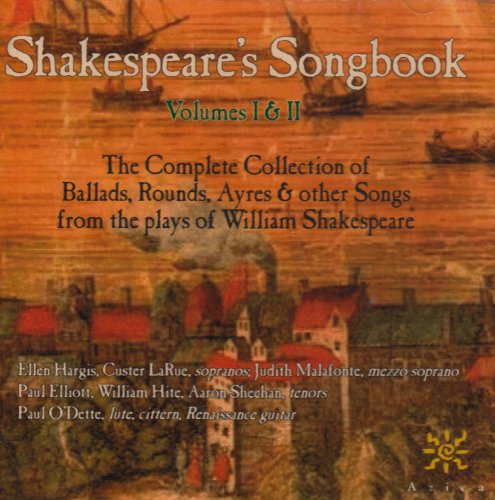

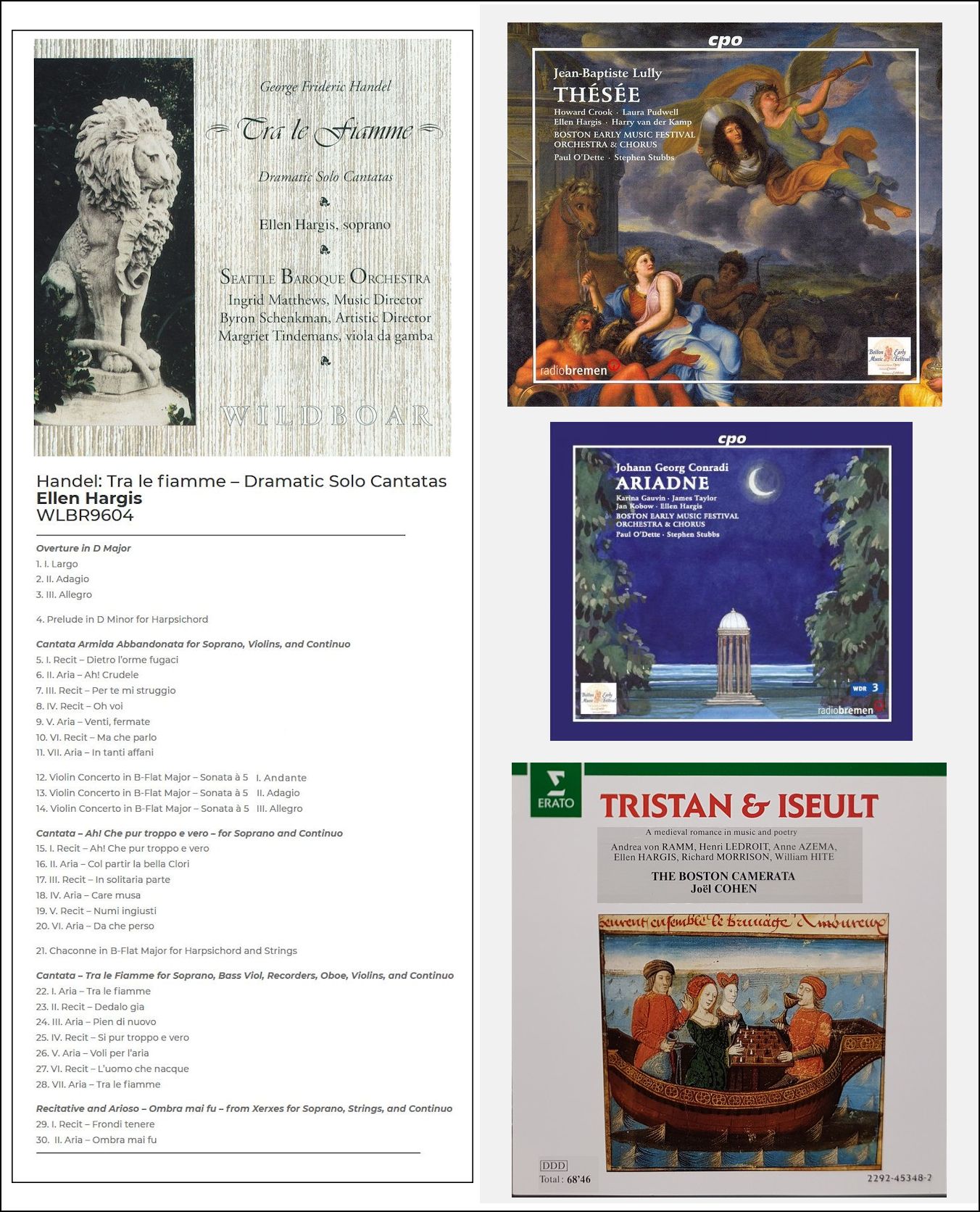

Soprano Ellen Hargis is one of America’s premier early music singers,

specializing in repertoire ranging from ballads to opera and oratorio.

She has worked with many of the foremost period music conductors of the

world, including Andrew

Parrott, Gustav Leonhardt, Daniel Harding, Paul Goodwin, John Scott, Monica

Huggett, Jane Glover,

Nicholas Kraemer, Harry Bickett, Simon Preston, Paul Hillier,

Craig Smith, and Jeffery Thomas. She has performed with The Saint

Paul Chamber Orchestra, The Virginia Symphony, Washington Choral

Arts Society, Long Beach Opera, CBC Radio Orchestra, Freiburg Baroque

Orchestra, Tragicomedia, The Mozartean Players, Fretwork, the Seattle

Baroque Orchestra, Emmanuel Music and the Mark Morris Dance Group.

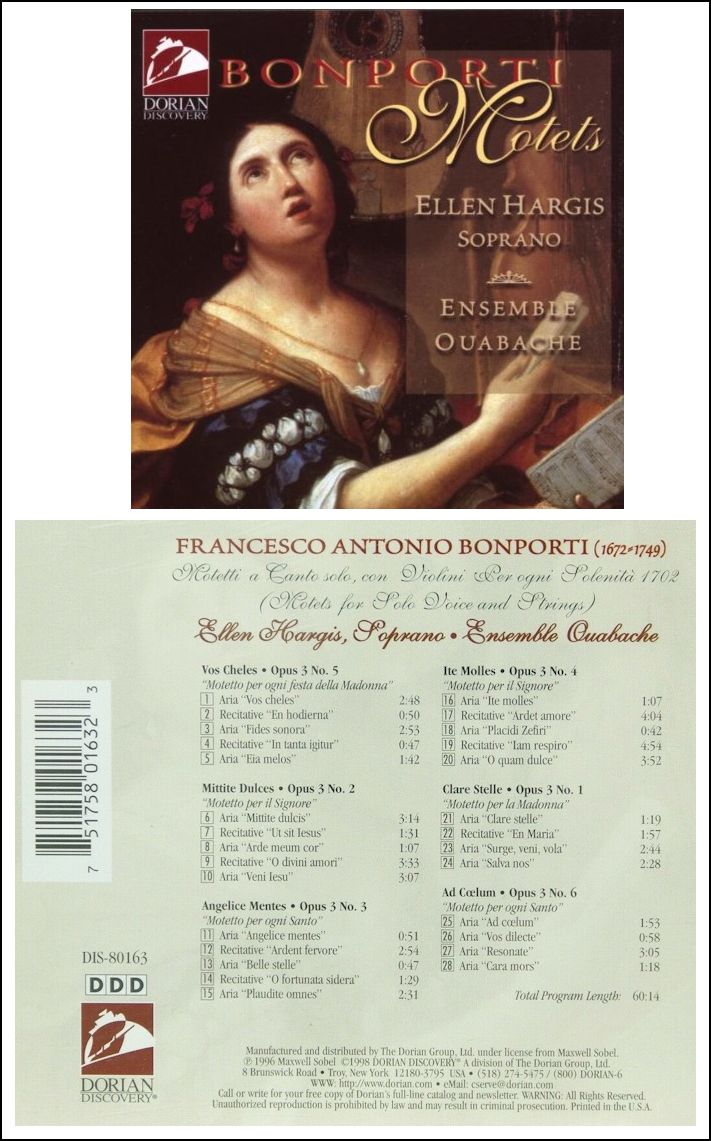

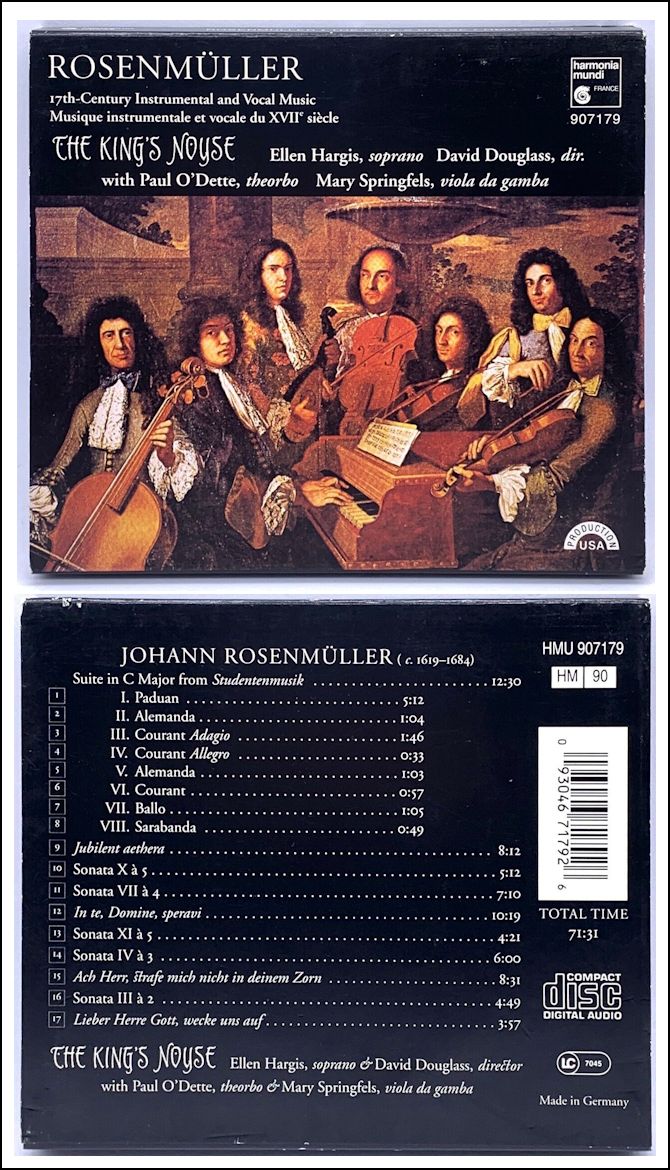

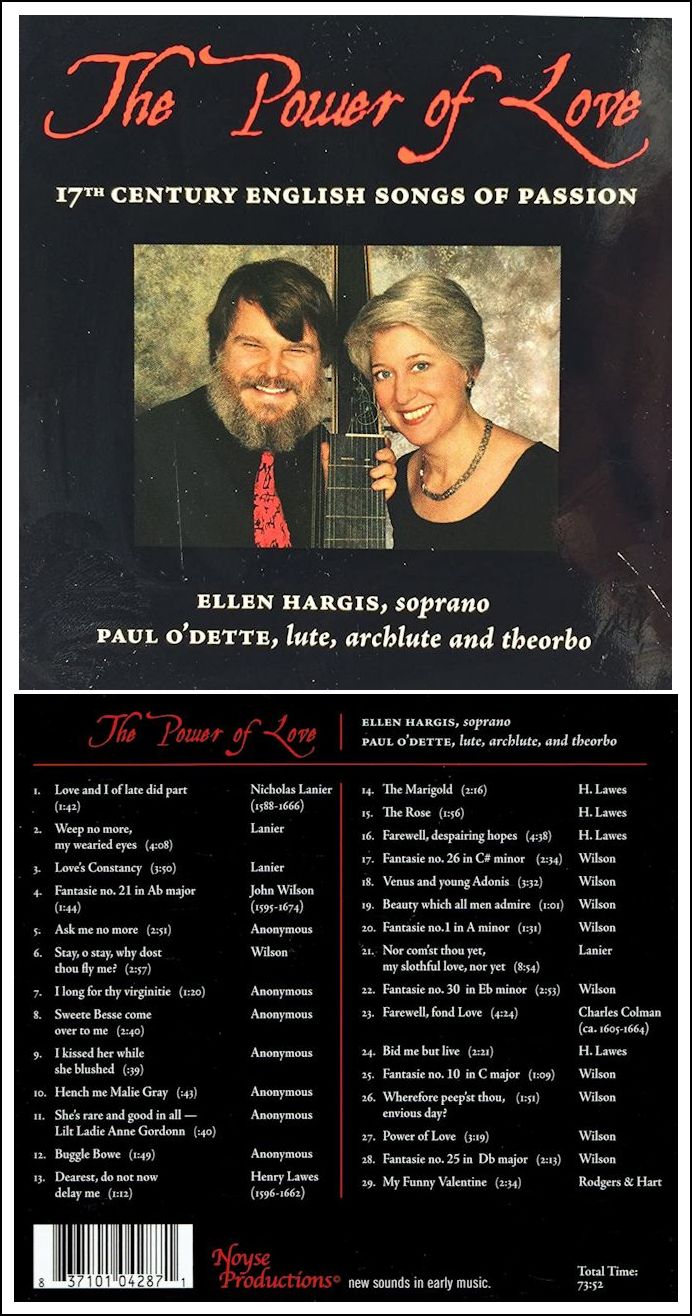

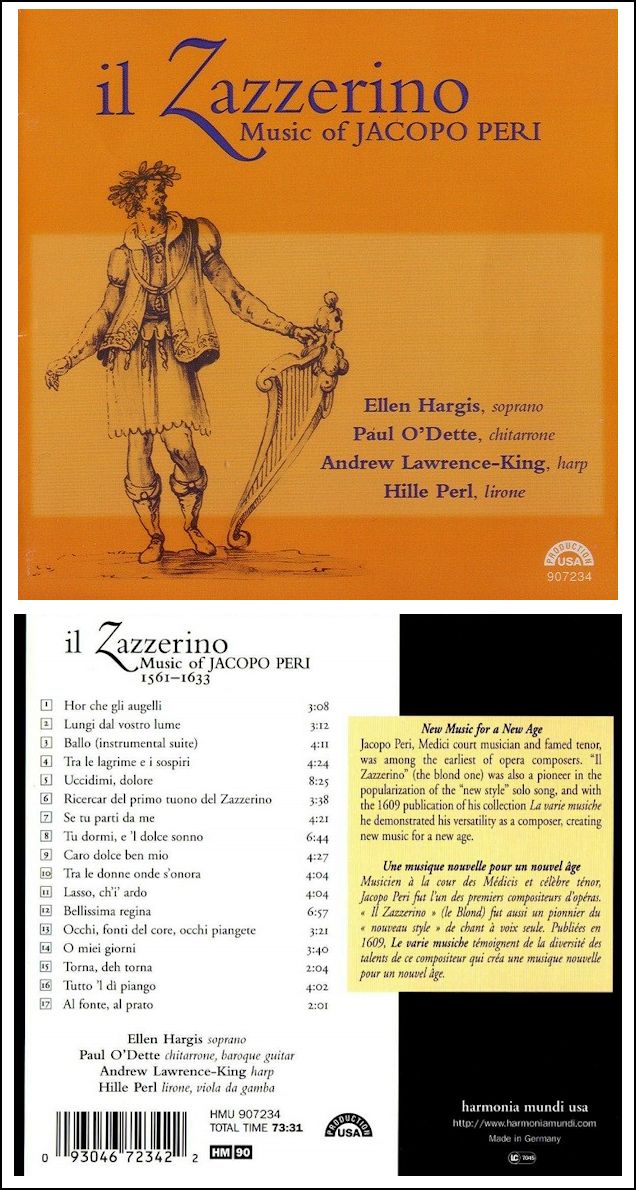

Hargis has performed at many of the world’s leading festivals including the Adelaide Festival (Australia), Utrecht Festival (Holland), Resonanzen Festival (Vienna), Tanglewood, the New Music America Festival, Festival Vancouver, the Berkeley Festival (California), and is a frequent guest at the Boston Early Music Festival. Her discography embraces repertoire from medieval to contemporary music. She has recorded the leading role of Aeglé in Lully’s Thésée for CPO, which was nominated for a Grammy Award for Best Opera Recording in 2008, as well as Conradi’s opera Ariadne, also nominated for a Grammy Award. She is featured on a dozen Harmonia Mundi recordings including a critically acclaimed solo recital disc of music by Jacopo Peri, and in Arvo Pärt’s Berlin Mass with Theatre of Voices, and two recital discs with Paul O’Dette on Noyse Productions. Hargis teaches voice at Case Western Reserve University in Cleveland, and is Artist-in-Residence with the Newberry Consort at the University of Chicago and Northwestern University. |

At the beginning of 1998, Hargis was back in Chicago,

and graciously agreed to spend an hour with me. We spoke about various

aspects of her career, and the special challenges of performing Early Music

as the ’90s were winding down.

At the beginning of 1998, Hargis was back in Chicago,

and graciously agreed to spend an hour with me. We spoke about various

aspects of her career, and the special challenges of performing Early Music

as the ’90s were winding down. Hargis: [Thinks a moment] It

changes so much. The social context of concerts, for instance, is

something that doesn’t have much of a continuation from very early to very

late. The modern phenomenon of a concert or a recital in a concert

hall is very much a modern phenomenon. So, when we do early music

in that context, it’s very unhistorical.

Hargis: [Thinks a moment] It

changes so much. The social context of concerts, for instance, is

something that doesn’t have much of a continuation from very early to very

late. The modern phenomenon of a concert or a recital in a concert

hall is very much a modern phenomenon. So, when we do early music

in that context, it’s very unhistorical. BD: [Gently protesting] But that

leaves a big gaping hole in the Romantic Century.

BD: [Gently protesting] But that

leaves a big gaping hole in the Romantic Century. BD: Do you keep finding new tools?

BD: Do you keep finding new tools?

| Luigi Rossi (c. 1597

– 20 February 1653) was an Italian Baroque composer. Born in Torremaggiore,

a small town near Foggia, in the ancient kingdom of Naples, at an early

age he went to Naples where he studied music with the Franco-Flemish composer

Jean de Macque, organist of the Santa Casa dell’Annunziata and maestro

di cappella to the Spanish viceroy. Rossi later entered the service

of the Caetani, dukes of Traetta. Rossi composed two operas: Il palazzo incantato, which was given at Rome in 1642; and Orfeo, written after he was invited by Cardinal Mazarin in 1646 to go to Paris for that purpose, and given its premiere there in 1647. Rossi returned to France in 1648 hoping to write another opera, but no production was possible because the court had sought refuge outside Paris. Rossi returned to Rome by 1650 and never attempted anything more for the stage. A collection of cantatas published in 1646 describes him as musician

to Cardinal Antonio Barberini, while Giacomo Antonio Perti in 1688 speaks

of him along with Carissimi and Cesti as "the three greatest lights of

our profession." Orfeo (Orpheus) is an opera in three acts,

a prologue and an epilogue by Rossi. The libretto, by Francesco Buti, is

based on the myth of Orpheus and Eurydice. Orfeo premiered at the

Théâtre du Palais-Royal in Paris on 2 March 1647. It was one

of the earliest operas to be staged in France. Rossi had already written one opera, Il palazzo incantato,

for Rome. This aroused the interest of the French first minister, the

Italian-born Cardinal Mazarin, who was eager to bring Italian culture

to Paris and hired Rossi in 1646 to write an opera for the Paris carnival

the following year. During his stay in France, Rossi learned that his

wife, Costanza, had died, and the grief he felt influenced the music he

was writing. The premiere was given a magnificent staging with the sets

and stage machinery designed by Giacomo Torelli. Over 200 men were employed

to work on the scenery. The choreography was by Giovan Battista Balbi.

The performance, which lasted six hours, was a triumph. However, Rossi

proved to be a victim of his own success. The expense of the performance

was just one of many reasons stoking popular discontent against Cardinal

Mazarin, which soon broke out into full-scale rebellion (the Fronde).

When Rossi returned to Paris in December, 1647, he found the court had

fled Paris and his services were no longer required.

* * * *

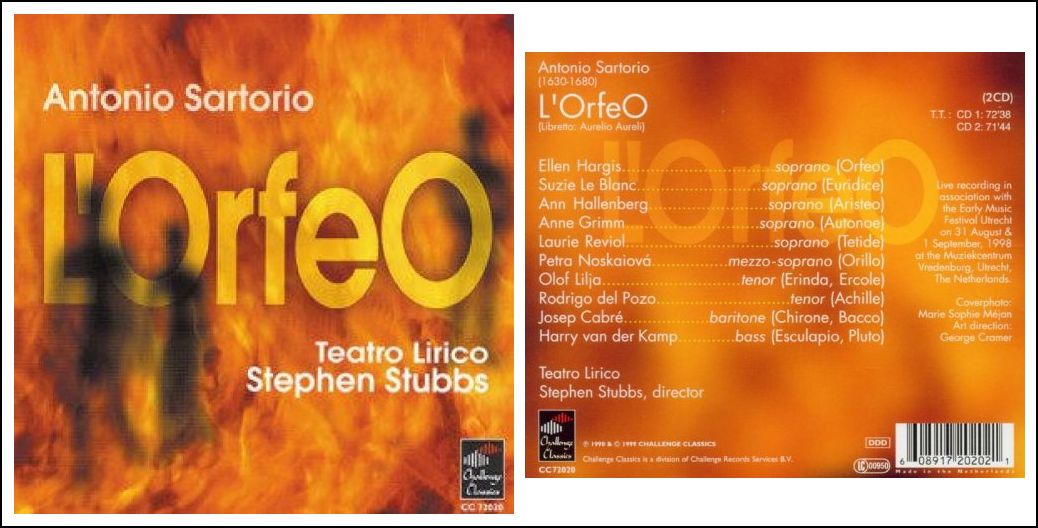

* Antonio Sartorio (1630 – 30 December 1680) was an Italian composer active mainly in Venice, Italy, and in Hanover, Germany. He was a leading composer of operas in his native Venice in the 1660s and 1670s, and was also known for composing in other genres of vocal music. Between 1665 and 1675 he spent most of his time in Hanover, where he held the post of Kapellmeister to Duke Johann Friedrich of Brunswick-Lüneburg – returning frequently to Venice to compose operas for the Carnival. In 1676 he became vice maestro di capella at San Marco in Venice. Orfeo (Orpheus) is an opera in three acts by Sartorio. The libretto, by Aurelio Aureli, is based on the myth of Orpheus and Eurydice. It was first performed at the Teatro San Salvatore, Venice in 1672. With its clear division between arias (of which there are about 50) and recitative, the work marks a transition in style between the Venetian opera of Francesco Cavalli and the new form of opera seria.

|

|

It was used in Italian operas and oratoriums to accompany the human voice, especially the gods. Because the lira da gamba cannot play the bass, there must be a bass instrument, theorbo, harpsichord or viola da gamba. Sources describe that the instrument was "used for the special sound, although it is an imperfect instrument." The Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians [edited by Stanley Sadie] describes the lirone as essentially a larger version of the lira da braccio, which has a similar wide fingerboard, flat bridge, and leaf-shaped pegbox with frontal pegs. Its flat bridge allows for the playing of chords of between three and five notes.The lirone was primarily used in Italy during the late 16th and early 17th centuries (particularly in the time of Claudio Monteverdi) to provide continuo, or harmony for the accompaniment of vocal music. It was frequently used in Catholic churches, particularly by Jesuits. Despite the resurgence in Baroque instrument performance during the 20th century, only a handful of musicians play the lirone. |

© 1998 Bruce Duffie

This conversation was recorded in Chicago on January 13, 1998. Portions were broadcast on WNIB three years later. This transcription was made in 2021, and posted on this website at that time. My thanks to British soprano Una Barry for her help in preparing this website presentation.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website, click here.

Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM, as well as on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio.

You are invited to visit his website for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.