|

John Jenkins [image shown at right] (1592 – 27 October

1678), was an English composer who was born in Maidstone, Kent and who

died at Kimberley, Norfolk. Jenkins was a long-active and prolific composer

whose many years of life, spanning the time from William Byrd to Henry

Purcell, witnessed great changes in English music. He is noted for developing

the viol consort fantasia, being influenced in the 1630s by an earlier generation

of English composers including Alfonso Ferrabosco the younger, Thomas Lupo,

John Coprario and Orlando Gibbons. Jenkins composed numerous four-, five-,

and six-part fantasias for viol consort, almans, courants and pavanes,

and he breathed new life into the antiquated form of the In Nomine.

He was less experimental than his friend William Lawes. Jenkins's music

was more conservative than that of many of his contemporaries. It is

characterized by a sensuous lyricism, highly skilled craftsmanship, and

an original usage of tonality and counterpoint.

John Jenkins [image shown at right] (1592 – 27 October

1678), was an English composer who was born in Maidstone, Kent and who

died at Kimberley, Norfolk. Jenkins was a long-active and prolific composer

whose many years of life, spanning the time from William Byrd to Henry

Purcell, witnessed great changes in English music. He is noted for developing

the viol consort fantasia, being influenced in the 1630s by an earlier generation

of English composers including Alfonso Ferrabosco the younger, Thomas Lupo,

John Coprario and Orlando Gibbons. Jenkins composed numerous four-, five-,

and six-part fantasias for viol consort, almans, courants and pavanes,

and he breathed new life into the antiquated form of the In Nomine.

He was less experimental than his friend William Lawes. Jenkins's music

was more conservative than that of many of his contemporaries. It is

characterized by a sensuous lyricism, highly skilled craftsmanship, and

an original usage of tonality and counterpoint.

Little is known of his early life. The son of Henry Jenkins, a carpenter

who occasionally made musical instruments, he may have been the "Jack Jenkins"

employed in the household of Anne Russell, Countess of Warwick in 1603. The

first positive historical record of Jenkins is amongst the musicians who

performed the masque The Triumph of Peace in 1634 at the court of

king Charles I. Jenkins was considered a virtuoso on the lyra viol. King

Charles I commented that Jenkins did "wonders on an inconsiderable

instrument."

When the English Civil War broke out in 1642 it forced Jenkins,

like many others, to migrate to the rural countryside. During the

1640s he was employed as music-master to two Royalist families, the

Derham family at West Dereham and Hamon le Strange of Hunstanton. He

was also a friend of the composer William Lawes (1602–1645), who was

shot and died in battle at the siege of Chester.

Around 1640 Jenkins revived the In Nomine, an archaic form

for a consort of viols, based upon a traditional plainsong theme.

He wrote a notable piece of programme music consisting of a pavane

and galliard depicting the clash of opposing sides, the mourning for

the dead and the celebration of victory after the siege of Newark (1646).

In the 1650s Jenkins became resident music-master of Lord Dudley

North in Cambridgeshire, whose son Roger wrote his biography. It was

in these years, during the Commonwealth under Oliver Cromwell, in the

absence of much competition or organised music-making, that Jenkins

took the occasion to write more than 70 suites for amateur household

players.

William Lawes [image shown at left] (April

1602 – 24 September 1645) was an English composer and musician.

He was the son of Thomas Lawes, a vicar choral at Salisbury Cathedral,

and brother to Henry Lawes, a very successful composer in his own right.

His patron, Edward Seymour, Earl of Hertford, apprenticed him to

the composer John Coprario, which probably brought Lawes into contact

with Charles, Prince of Wales at an early age. Both William and his

elder brother Henry received court appointments after Charles succeeded

to the British throne as Charles I. William was appointed as "musician

in ordinary for lutes and voices" in 1635, but had been writing music

for the court prior to this.

Lawes spent all his adult life in Charles's employ. He composed

secular music and songs for court masques (and doubtless played in them),

as well as sacred anthems and motets for Charles's private worship.

He is most remembered today for his sublime viol consort suites for

between three and six players, and his lyra viol music. His use of

counterpoint and fugue and his tendency to juxtapose bizarre, spine-tingling

themes next to pastoral ones in these works made them disfavoured

in the centuries after his death. They have only become widely available

in recent years.

When Charles's dispute with Parliament led to the outbreak

of the Civil War, Lawes joined the Royalist army. During the Siege

of York, Lawes was living in the city, and wrote at least one piece of

music as a direct result of the military situation – the round See

how Cawood's dragon looks, a vivid and defiant response to the Parliamentarian

capture of Cawood Castle, about ten miles from York. He was given a post

in the King's Life Guards, which was intended to keep him out of danger.

Despite this, he was "casually shot" by a Parliamentarian in the rout

of the Royalists at Rowton Heath, near Chester, on 24 September 1645.

Although the King was in mourning for his kinsman Bernard Stuart (killed

in the same defeat), he instituted a special mourning for Lawes, apparently

honoring him with the title of "Father of Musick."

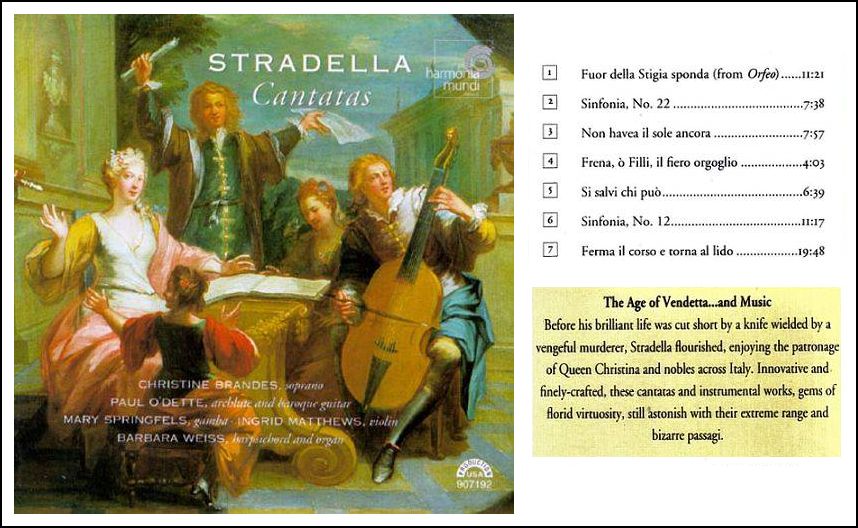

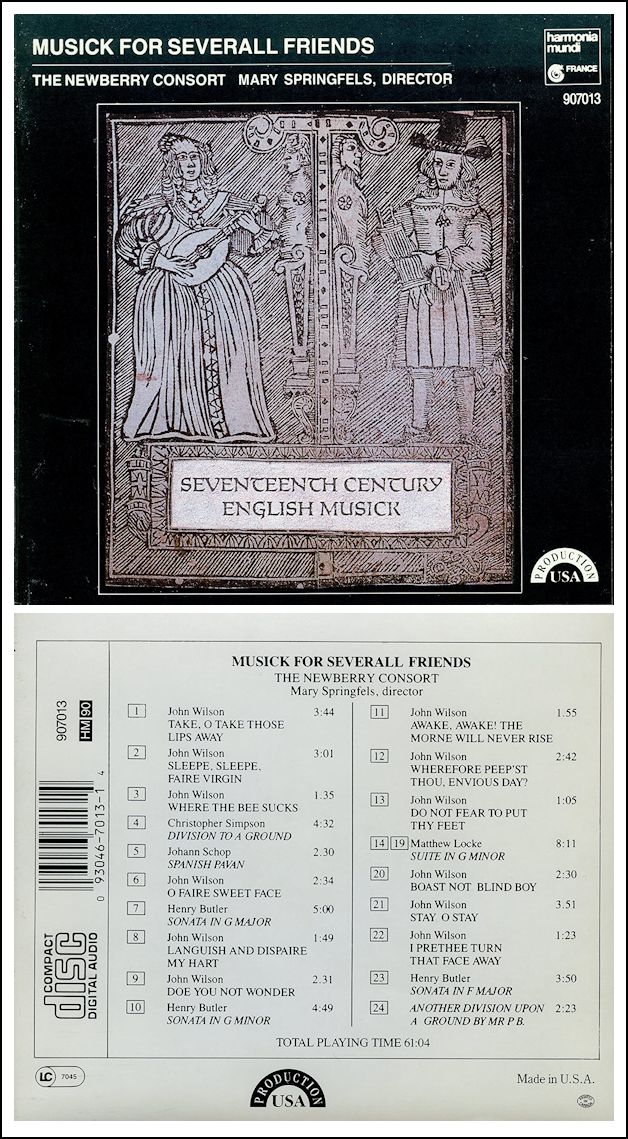

Henry Butler [no image] (born in England, died 1652 in

Spain) was an English composer and viol player. From 1623 until his death

he lived in Spain, serving as a musician in the chapel of Philip IV,

under the names Enrique (or Enrrique) Botelero and

Enrico Butler.

Butler and William Young, an English viol player working at

the Austrian court in Innsbruck, were the first English composers to

call their works sonatas. Young published 11 sonatas in 1653, whereas

all of Butler's works survived only in undated manuscripts. His three

sonatas were for violin, bass viol and continuo.

William Young [no image] (died 23 April 1662) was an English

viol player and composer of the Baroque era, who worked at the court

of Ferdinand Charles, Archduke of Austria in Innsbruck. The details of

Young's origins are unknown. By 1652 he was a chamber musician at the

Innsbruck court, where "the Englishman", as he was called, was a highly

regarded viol player and composer. The design of his English-made viol

influenced that of some of the viols built by Jakob Stainer, the Austrian

luthier. Young's 11 sonatas for two, three, and four parts and continuo,

published in Innsbruck in 1653, are known to have reached England.

In modern times, the 11 sonatas were rediscovered by William Gillies

Whittaker. He found them in manuscript in Uppsala University Library

in Sweden, and published them in 1930. He is not to be confused with William

Young (died 1671), another musician, who played violin and flute at the

court of Charles II of England from 1661.

Heinrich Ignaz Franz Biber [image shown at right]

(12 August 1644 (baptised) – 3 May 1704) was a Bohemian-Austrian composer

and violinist. Born in the small Bohemian town of Wartenberg (now Stráž

pod Ralskem), Biber worked in Graz and Kremsier (now Kroměříž)

before he illegally left his Kremsier employer, Prince-Bishop Carl Liechtenstein-Kastelkorn,

and settled in Salzburg. He remained there for the rest of his life,

publishing much of his music but apparently seldom, if ever, giving concert

tours.

Biber was one of the most important composers for the violin in

the history of the instrument. His technique allowed him to easily reach

the 6th and 7th positions, employ multiple stops in intricate polyphonic

passages, and explore the various possibilities of scordatura tuning. Biber

also wrote operas, sacred music and music for chamber ensemble, and one of

the earliest known pieces for solo violin, the monumental passacaglia of

the Mystery Sonatas. During Biber's lifetime, his music was known

and imitated throughout Europe. In the late 18th century he was named the

best violin composer of the 17th century by music historian Charles Burney.

In the late 20th century Biber's music, especially the Mystery Sonatas,

enjoyed a renaissance. Today, it is widely performed and recorded.

Johann Heinrich Schmelzer [image shown at left] (c.

1620–1623 – between 29 February and 20 March 1680) was an Austrian

composer and violinist of the middle Baroque era. Almost nothing is

known about his early years, but he seems to have arrived in Vienna

during the 1630s, and remained composer and musician at the Habsburg

court for the rest of his life. He enjoyed a close relationship with Emperor

Leopold I, was ennobled by him, and rose to the rank of Kapellmeister

in 1679. He died during a plague epidemic only months after getting the

position.

Schmelzer was one of the most important violinists of the period,

and an important influence on later German and Austrian composers

for violin. He made substantial contributions to the development of violin

technique, and promoted the use and development of sonata and suite forms

in Austria and South Germany. He was the leading Austrian composer of

his generation, and an influence on Heinrich Ignaz Biber.

Schmelzer's Sonatae unarum fidium of 1664 was the first

collection of sonatas for violin and basso continuo to be published

by a German-speaking composer. It contains the brilliant virtuosity,

sectional structure, and lengthy ground-bass variations typical of the

mid-Baroque violin sonata.

Georg Muffat [image shown at right] (1 June 1653 – 23

February 1704) was a Baroque composer and organist. He is best known

for the remarkably articulate and informative performance directions

printed along with his collections of string pieces Florilegium

Primum and Florilegium Secundum (First and Second Bouquets)

in 1695 and 1698.

Georg Muffat [image shown at right] (1 June 1653 – 23

February 1704) was a Baroque composer and organist. He is best known

for the remarkably articulate and informative performance directions

printed along with his collections of string pieces Florilegium

Primum and Florilegium Secundum (First and Second Bouquets)

in 1695 and 1698.

Georg Muffat was born in Megève, Duchy of Savoy (now in

France), son of André Muffat (of Scottish descent) and Marguerite

Orsyand. He studied in Paris between 1663 and 1669, where his teacher is

often assumed to have been Jean Baptiste Lully.

After leaving Paris, he became an organist in Molsheim and Sélestat.

Later, he studied law in Ingolstadt, afterwards settling in Vienna.

He could not get an official appointment, so he travelled to Prague

in 1677, then to Salzburg, where he worked for the archbishop for some

ten years. In about 1680, he traveled to Italy, there studying the organ

with Bernardo Pasquini, a follower of the tradition of Girolamo Frescobaldi;

he also met Arcangelo Corelli, whose works he admired very much. From

1690 to his death, he was Kapellmeister to the bishop of

Passau.

Georg Muffat should not be confused with his son Gottlieb Muffat,

also a successful composer. Gottlieb Muffat [no image available]

(April 1690 – 9 December 1770), son of Georg Muffat, served as Hofscholar

under Johann Fux in Vienna from 1711 and was appointed to the position

of third court organist at the Hofkapelle in 1717. He acquired

additional duties over time, including the instruction of members of

the Imperial family, among them the future Empress Maria Theresa. He

was promoted to second organist in 1729 and first organist upon the accession

of Maria Theresa to the throne in 1741. He retired from official duties

at the court in 1763. It is well established that Handel borrowed copiously

from his contemporaries, including Muffat. It is not known with certainty

whether Handel and Muffat had any personal knowledge of each other, but

their positions as leading musicians in major European capitals might

imply at least a mutual awareness. There is a copy, in Muffat's own hand,

of Handel's Suites des pieces (1720) which Muffat supplied with

numerous ornaments along with a few variants of his own design.

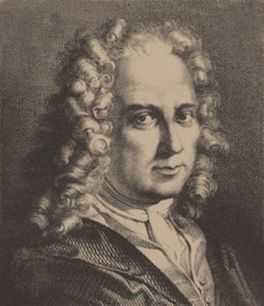

Johann Adam Reincken [image shown at left] (also

Jan Adams, Jean Adam, Reinken, Reinkinck, Reincke,

Reinicke, Reinike; baptized 10 December 1643 – 24 November 1722)

was a Dutch/German organist and composer. He was one of the most important

composers of the 17th century, a friend of Dieterich Buxtehude and a

major influence on Johann Sebastian Bach. Unfortunately, very few of

his works survive to this day.

Reincken received primary music education in Deventer in 1650–1654,

from Lucas van Lennick, organist of the Grote kerk (Lebuinuskerk).

In 1654 he departed for Hamburg to study under Heinrich Scheidemann,

a pupil of Jan Pieterszoon Sweelinck, organist of St. Katharine's Church

(Katharinenkirche). In 1657 he returned to Deventer and became

organist of the Bergkerk on 11 March. However, after only a year he

left for Hamburg again, this time to become Scheidemann's assistant.

When the older composer died in 1663, Reincken succeeded him at St.

Katharine's. In 1665 he married one of Scheidemann's daughters, and

their only child Margaretha-Maria was born three years later.

The composer kept his position at St. Katharine's until his

death in 1722, although in 1705 some of the church elders attempted

to appoint Johann Mattheson as Reincken's successor. Unlike many other

contemporary organists, Reincken died wealthy. In his lifetime he

was heralded as one of the best organists in Germany. He knew Dieterich

Buxtehude closely, and influenced Vincent Lübeck and Johann Sebastian

Bach. Bach was evidently deeply impressed by Reincken's music, arranging

several of the works from Hortus musicus (as BWV 954, 965

and 966). In 2006, the earliest known Bach autograph was discovered in

Weimar: a copy of Reincken's An Wasserflüssen Babylon,

which Bach made for his then teacher Georg Böhm in Lüneburg in

1700.

|

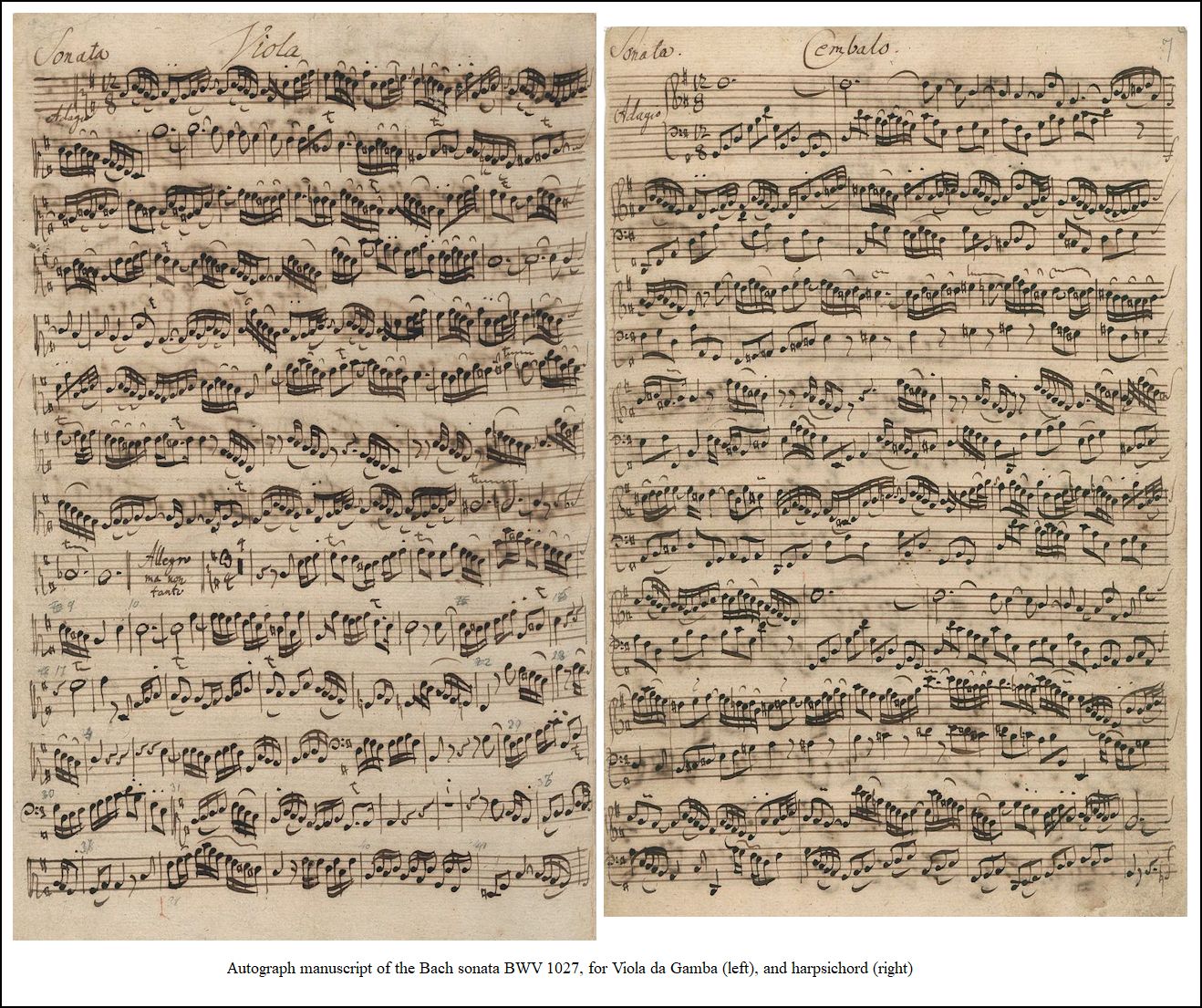

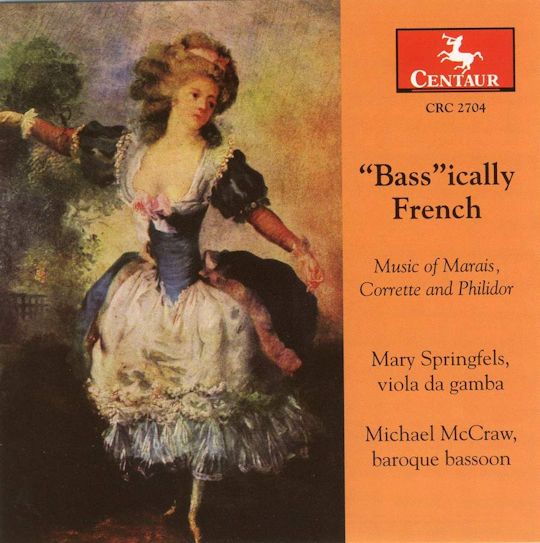

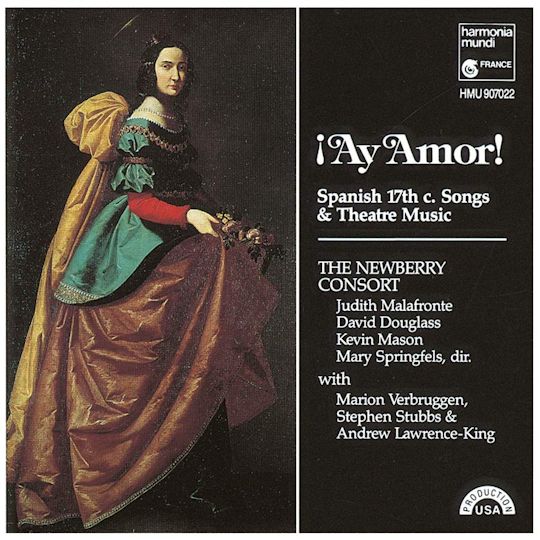

Springfels: Bach wrote three sonatas [image of

BWV 1027 is shown at the bottom of this webpage], and CPE Bach,

his son, wrote three very, very great sonatas, none of which have

been recorded because they’re too hard. They’re early Classical

pieces.

Springfels: Bach wrote three sonatas [image of

BWV 1027 is shown at the bottom of this webpage], and CPE Bach,

his son, wrote three very, very great sonatas, none of which have

been recorded because they’re too hard. They’re early Classical

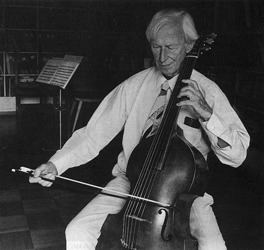

pieces. BD: [While basking in the

sound] There’s no endpin.

BD: [While basking in the

sound] There’s no endpin. Wenzinger received his basic musical training at

the Basel Conservatory, then went on to study cello with Paul

Grümmer and music theory with Philipp Jarnach at the Hochschule

für Musik in Cologne. He then took private cello lessons with

Emanuel Feuermann in Berlin. Wenzinger served as first cellist

in the Bremen City Orchestra (1929–1934) and the Basel Allgemeine

Musikgesellschaft (1936–1970).

Wenzinger received his basic musical training at

the Basel Conservatory, then went on to study cello with Paul

Grümmer and music theory with Philipp Jarnach at the Hochschule

für Musik in Cologne. He then took private cello lessons with

Emanuel Feuermann in Berlin. Wenzinger served as first cellist

in the Bremen City Orchestra (1929–1934) and the Basel Allgemeine

Musikgesellschaft (1936–1970).

BD: It is played between

the legs, rather than under the chin?

BD: It is played between

the legs, rather than under the chin?

BD: [With a gentle nudge]

So then, Augenmusik [music for the eye] is

not something that just modernists are doing?

BD: [With a gentle nudge]

So then, Augenmusik [music for the eye] is

not something that just modernists are doing?

Guillaume Du Fay (

Guillaume Du Fay (

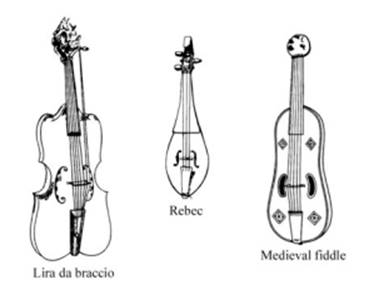

The medieval fiddle emerged in 10th-century Europe, deriving

from the Byzantine lira (Greek: λύρα, Latin: lira, English:

lyre), a bowed string instrument of the Byzantine Empire,

and ancestor of most European bowed instruments.

The medieval fiddle emerged in 10th-century Europe, deriving

from the Byzantine lira (Greek: λύρα, Latin: lira, English:

lyre), a bowed string instrument of the Byzantine Empire,

and ancestor of most European bowed instruments.

John Jenkins [image shown at right] (1592 – 27 October

1678), was an English composer who was born in Maidstone, Kent and who

died at Kimberley, Norfolk. Jenkins was a long-active and prolific composer

whose many years of life, spanning the time from William Byrd to Henry

Purcell, witnessed great changes in English music. He is noted for developing

the viol consort fantasia, being influenced in the 1630s by an earlier generation

of English composers including Alfonso Ferrabosco the younger, Thomas Lupo,

John Coprario and Orlando Gibbons. Jenkins composed numerous four-, five-,

and six-part fantasias for viol consort, almans, courants and pavanes,

and he breathed new life into the antiquated form of the In Nomine.

He was less experimental than his friend William Lawes. Jenkins's music

was more conservative than that of many of his contemporaries. It is

characterized by a sensuous lyricism, highly skilled craftsmanship, and

an original usage of tonality and counterpoint.

John Jenkins [image shown at right] (1592 – 27 October

1678), was an English composer who was born in Maidstone, Kent and who

died at Kimberley, Norfolk. Jenkins was a long-active and prolific composer

whose many years of life, spanning the time from William Byrd to Henry

Purcell, witnessed great changes in English music. He is noted for developing

the viol consort fantasia, being influenced in the 1630s by an earlier generation

of English composers including Alfonso Ferrabosco the younger, Thomas Lupo,

John Coprario and Orlando Gibbons. Jenkins composed numerous four-, five-,

and six-part fantasias for viol consort, almans, courants and pavanes,

and he breathed new life into the antiquated form of the In Nomine.

He was less experimental than his friend William Lawes. Jenkins's music

was more conservative than that of many of his contemporaries. It is

characterized by a sensuous lyricism, highly skilled craftsmanship, and

an original usage of tonality and counterpoint.

Georg Muffat [image shown at right] (1 June 1653 – 23

February 1704) was a Baroque composer and organist. He is best known

for the remarkably articulate and informative performance directions

printed along with his collections of string pieces Florilegium

Primum and Florilegium Secundum (First and Second Bouquets)

in 1695 and 1698.

Georg Muffat [image shown at right] (1 June 1653 – 23

February 1704) was a Baroque composer and organist. He is best known

for the remarkably articulate and informative performance directions

printed along with his collections of string pieces Florilegium

Primum and Florilegium Secundum (First and Second Bouquets)

in 1695 and 1698.