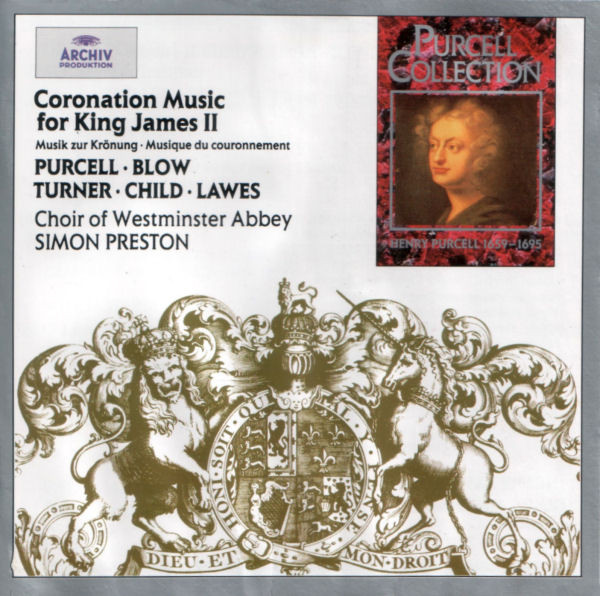

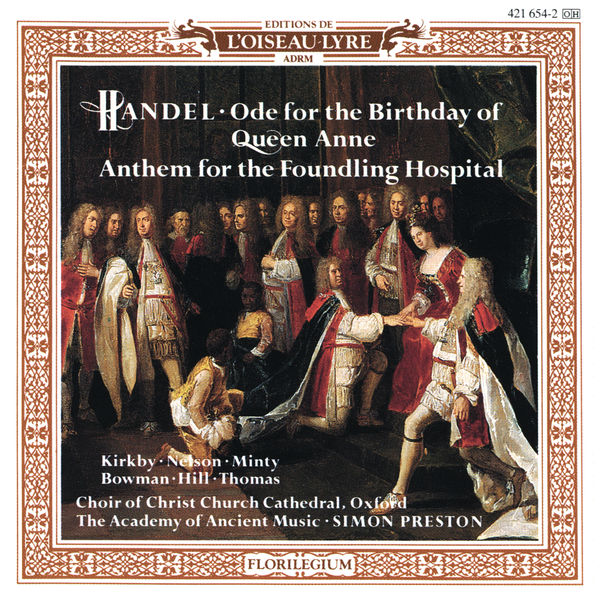

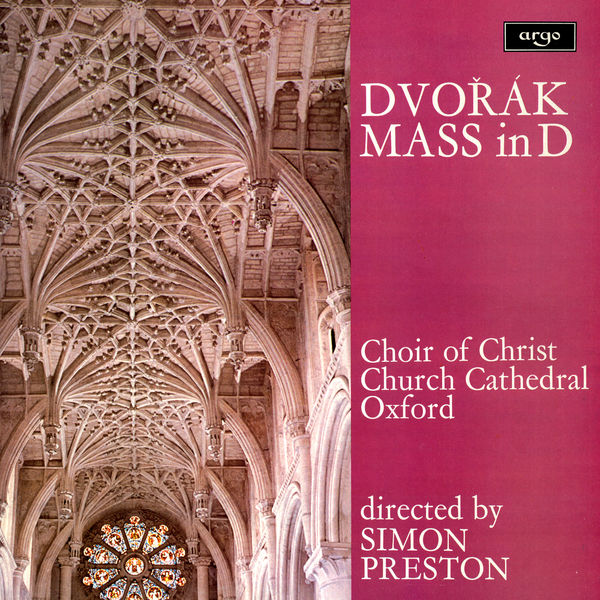

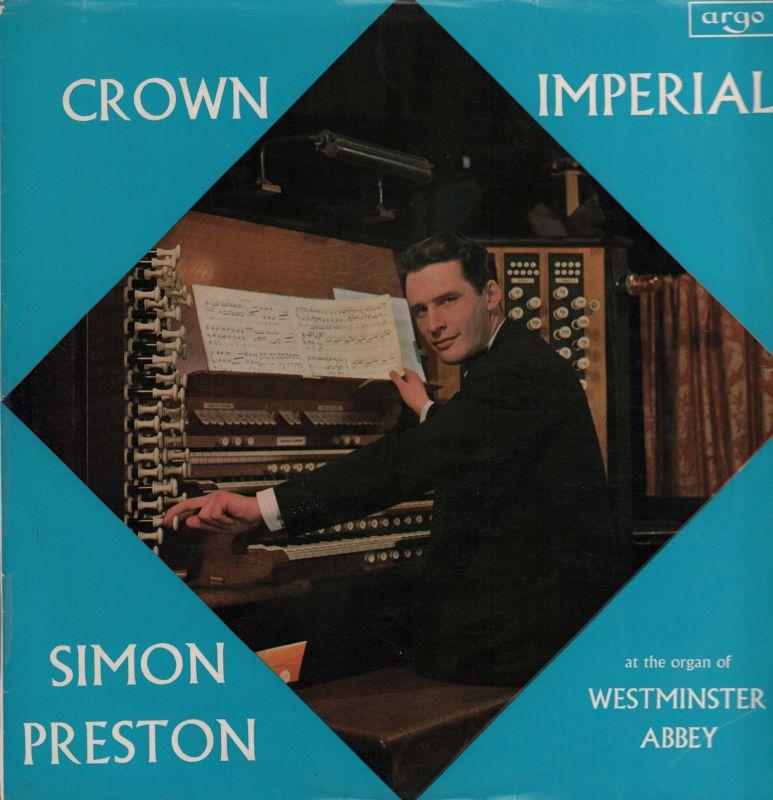

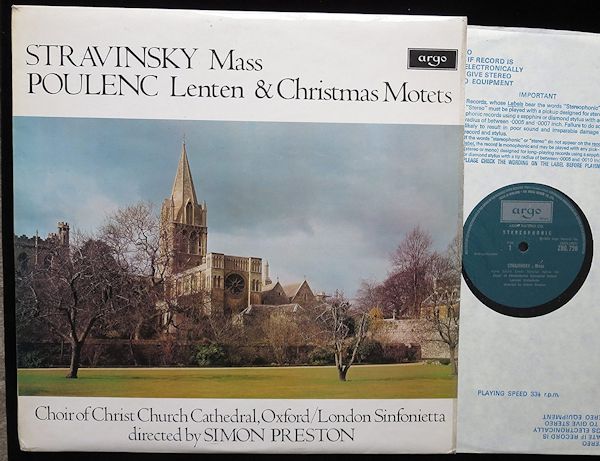

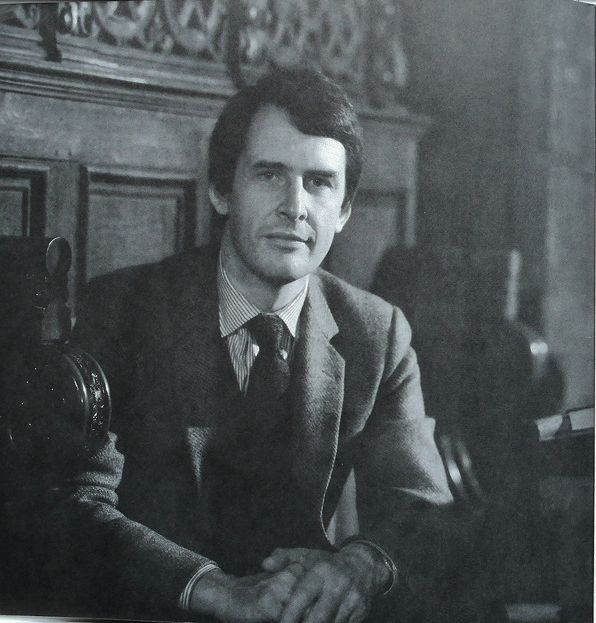

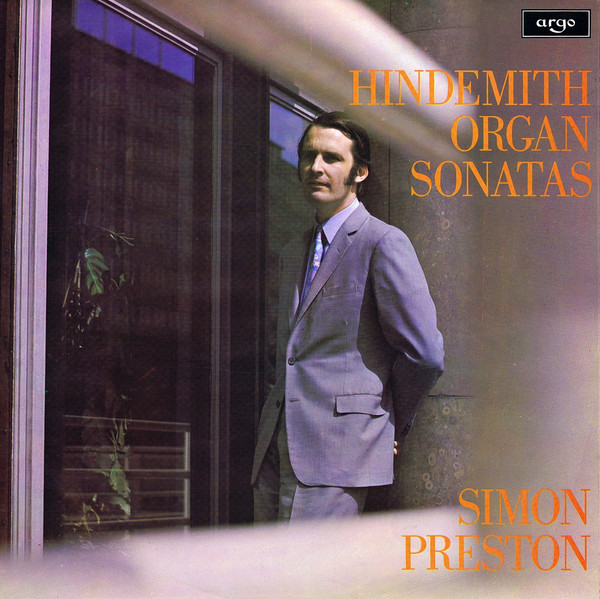

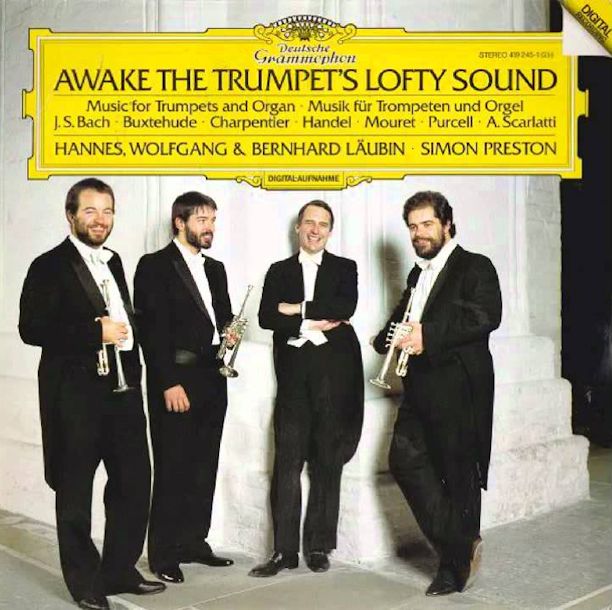

* * * * * Simon Preston made his debut at the Royal Festival Hall, London in March 1962, performing the organ solos in Janacek’s Glagolitic Mass. However, prior to that, devotees of the annual Christmas Eve broadcast from King’s College, Cambridge of the Festival of Nine Lessons and Carols had heard Simon Preston accompanying the Choir from the Chapel, where he had been a chorister as a boy, and where he returned later as Organ Scholar. Shortly after his London debut Mr. Preston was appointed Sub-Organist of Westminster Abbey, and later that same year appeared for the first time at the Henry Wood Promenade Concerts at the Royal Albert Hall. During that period he worked under many famous conductors, including Leopold Stokowski, Pierre Monteux, Leonard Bernstein and Benjamin Britten. In 1965 he made his first tour to the United States and Canada, and by the time he left Westminster Abbey in 1967 Mr. Preston was already an internationally acclaimed artist. In 1970 he became Organist of the Cathedral and Tutor in Music at Christ Church Oxford where his work with the choir won high praise. Fourteen years later in 1981, he was appointed Organist and Master of the Choristers at Westminster Abbey, where his work with the choir received great acclaim. He directed the music at the Royal Wedding of Sarah Ferguson and Prince Andrew in 1986, and was responsible for writing much of the “Salieri” music in the movie Amadeus. Since leaving Westminster Abbey in 1987 he has continued to pursue an active career as a highly sought-after concert organist. He recorded the Saint-Saëns “Organ” Symphony with the Berlin Philharmonic and James Levine, the Poulenc Concerto for Organ, Strings and Timpani with the Boston Symphony and Seiji Ozawa, and the Copland Symphony for Organ and Orchestra with the St. Louis Symphony Orchestra and Leonard Slatkin. Since his first tour in 1965, Simon Preston has been a regular visitor to the United States, often appearing as a guest artist at conventions of the American Guild of Organists as well as tours that have included most of the states in America. The description in a Vienna newspaper of Simon Preston as “a living legend” serves as a reminder that his recording career began nearly fifty-five years ago with the performance of a Gibbons Fantasia on a King’s College, Cambridge disc. There are currently nearly fifty of his CDs still available, including versions of the Handel Organ Concertos with both Yehudi Menuhin and Trevor Pinnock, and Bach’s 5th Brandenburg Concerto as harpsichord soloist, as well as many recordings with the choirs of both Westminster Abbey and Christ Church, Oxford. In 1971 Mr. Preston was awarded an “Edison Classique” for his recordings of Messiaen’s Les Corps Glorieux and Hindemith’s Organ Sonatas. The recording of Handel’s Coronation Anthems with the Westminster Abbey Choir conducted by Simon Preston was awarded a “Grand Prix du Disque” in 1983. In October of 2000 Deutsche Grammophon launched his complete recording of Bach’s organ works. For Simon Preston honors and accolades abound. The New York City Chapter of the AGO named him International Performer of the Year for 1987. Classic CD recently named Mr. Preston in its list, “The Greatest Players of the Century,” which included the entire classical music world. In 2009 Simon Preston was made a C.B.E (Commander of the British Empire) in the New Year’s Honours List, in 2011 he was made an honorary Student at Christ Church, Oxford University, and in November, 2011 he will be awarded an honorary doctorate by Mount Royal University, Calgary, Canada. -- From the program of a concert given at

the Yale University Institute of Sacred Music, 2011

|

||||||||||||

BD: What is it about these particular pieces that make

them your favorites?

BD: What is it about these particular pieces that make

them your favorites? BD: Is there ever a chance that it becomes over-prepared

and too well-rehearsed?

BD: Is there ever a chance that it becomes over-prepared

and too well-rehearsed? BD: I just wondered if you did a mixed

program, would you try to actually change the sound of the group from

one work to the next.

BD: I just wondered if you did a mixed

program, would you try to actually change the sound of the group from

one work to the next.

SP: No, I think it’s their expectation.

I don’t think they’ve caught up to what’s going on half the time.

SP: No, I think it’s their expectation.

I don’t think they’ve caught up to what’s going on half the time. BD: When you go around the world, you

play on all these different organs. About how long does it take

you to get into a new instrument, and figure out exactly what it can and

cannot do?

BD: When you go around the world, you

play on all these different organs. About how long does it take

you to get into a new instrument, and figure out exactly what it can and

cannot do?|

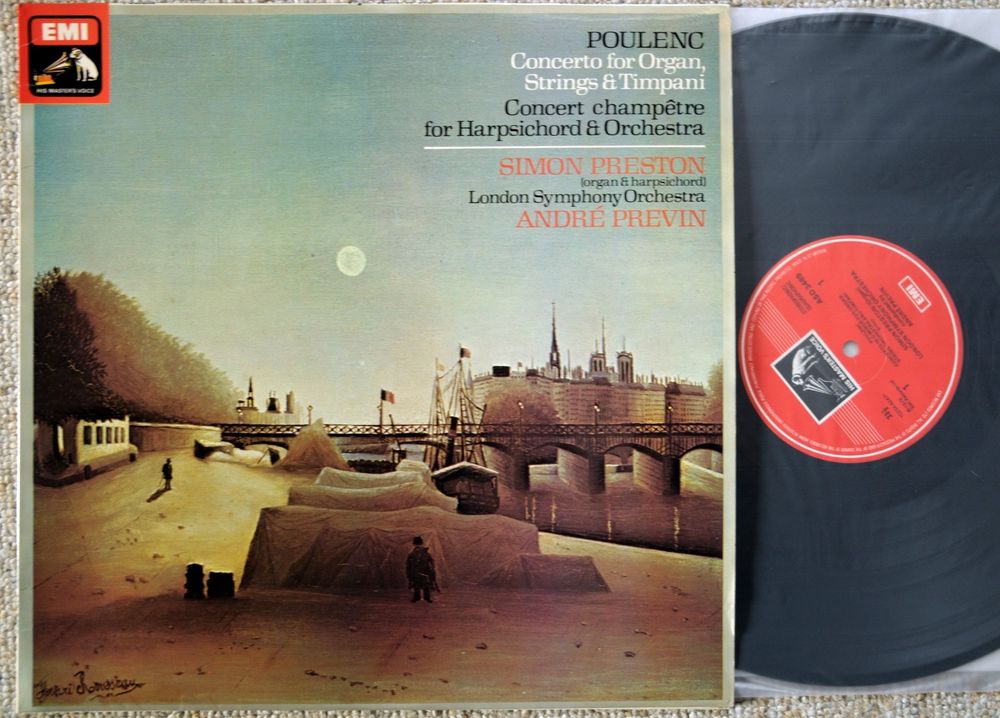

The Poulenc Organ Concerto was commissioned by Princess Edmond

de Polignac in 1934, as a piece with a chamber orchestra accompaniment

and an easy organ part that the princess could probably play herself.

The commission was originally given to Jean Françaix, who declined,

but Poulenc accepted. Poulenc quickly abandoned this idea for something

much more grandiose and ambitious. As he wrote in a letter to Françaix,

"The concerto...is not the amusing Poulenc of the Concerto for Two

Pianos, but more like a Poulenc en route for the cloister." Indeed,

Poulenc referred to it as being on the fringe of his religious works.

Poulenc himself had never actually composed for the organ before, and

so he studied great baroque masterpieces for the instrument by Johann Sebastian

Bach and Dieterich Buxtehude; the work's neo-baroque feel reflects this.

Poulenc was also advised about the instrument's registration and other

aspects by the organist Maurice Duruflé. Duruflé was also

the soloist in the private premiere of the work on 16 December 1938, with

Nadia Boulanger conducting, at Princess Edmond's salon. The first public

performance was in June 1939 at the Salle Gaveau in Paris, with Duruflé

once again the soloist and Roger Désormière conducting.

See my interview with André Previn

|

BD: In one of your biographies, it says that you are

a perfectionist. Is that a good or a bad term?

BD: In one of your biographies, it says that you are

a perfectionist. Is that a good or a bad term? BD: There’s nothing straining on the

back than when you’re working with pedal board?

BD: There’s nothing straining on the

back than when you’re working with pedal board? BD: Is playing the organ fun?

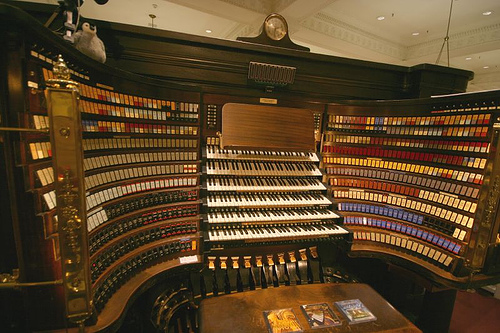

BD: Is playing the organ fun? The Wanamaker Grand Court Organ, in Philadelphia, is the largest fully

functioning pipe organ in the world. (The Boardwalk Hall Auditorium Organ

has more pipes but fewer ranks and at least 80% of the pipes have been unplayable

for most of its existence). The Wanamaker Organ is located within a spacious

7-story court at Macy's Center City (formerly Wanamaker's department store)

and played at least twice a day Monday through Saturday, and more frequently

during the Christmas season. The organ is featured at several special concerts

held throughout the year, including events featuring the Friends of the

Wanamaker Organ Festival Chorus and Brass Ensemble.

The Wanamaker Grand Court Organ, in Philadelphia, is the largest fully

functioning pipe organ in the world. (The Boardwalk Hall Auditorium Organ

has more pipes but fewer ranks and at least 80% of the pipes have been unplayable

for most of its existence). The Wanamaker Organ is located within a spacious

7-story court at Macy's Center City (formerly Wanamaker's department store)

and played at least twice a day Monday through Saturday, and more frequently

during the Christmas season. The organ is featured at several special concerts

held throughout the year, including events featuring the Friends of the

Wanamaker Organ Festival Chorus and Brass Ensemble.In its present configuration, the Wanamaker Organ has 28,750 pipes in 464 ranks. The organ console consists of six manuals with an array of stops and controls that command the organ. The organ's String Division forms the largest single organ chamber in the world. The instrument features eighty-eight ranks of string pipes built by the W.W. Kimball Company of Chicago. The organ is famed for its orchestra-like sound, coming from pipes that are voiced softer than usual, allowing an unusually rich build-up because of the massing of pipe-tone families. The artistic obligation entailed by the creation of this instrument has always been honored, with two curators employed in its constant and scrupulous care (what leads to the state of one of the best maintained organ in the world). The organ, with its regular program of concerts and recitals, was maintained by Wanamaker's throughout the chain's history, even as the company's financial fortunes waned. This level of dedication was maintained when corporate parentage shifted from the Wanamaker family to Carter Hawley Hale Stores followed by Woodward & Lothrop, Lord & Taylor, and finally to Macy's. |

SP: Yes, yes, that’s right. You haven’t to do much

else to it, no, no. It’s got it all. It’s self-sufficient.

It just needs to be touched — for the toccata!

[Both laugh] But I’m not one of those people who regards the organ

as opposition, as it were. You often hear organists talking

about ‘getting at the opposition’, as though it was something to

be feared and dreaded. To me, it’s a Stradivarius to take control

of.

SP: Yes, yes, that’s right. You haven’t to do much

else to it, no, no. It’s got it all. It’s self-sufficient.

It just needs to be touched — for the toccata!

[Both laugh] But I’m not one of those people who regards the organ

as opposition, as it were. You often hear organists talking

about ‘getting at the opposition’, as though it was something to

be feared and dreaded. To me, it’s a Stradivarius to take control

of.

© 1990 Bruce Duffie

This conversation was recorded in Evanston, Illinois, on May 1, 1990. Portions were broadcast on WNIB later that evening, and again in 1993 and 1998. This transcription was made in 2018, and posted on this website at that time. My thanks to British soprano Una Barry for her help in preparing this website presentation.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website, click here.

Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM.

You are invited to visit his website for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.