MH: I always knew that the day before it was going

to be like moving a ten-ton truck. I always knew that, but then you

have got to be real regular to predict when it would be. [Both laugh]

MH: I always knew that the day before it was going

to be like moving a ten-ton truck. I always knew that, but then you

have got to be real regular to predict when it would be. [Both laugh] MH: We are entertainers, absolutely; you can’t forget

that. If I went on and obliterated the audience, then I wouldn’t be

projecting anything out there because we are on stage to communicate.

We are communicators, so therefore, in that sense, we are entertainers and

whether it’s tragic or happy, it is still entertainment. So it’s both.

MH: We are entertainers, absolutely; you can’t forget

that. If I went on and obliterated the audience, then I wouldn’t be

projecting anything out there because we are on stage to communicate.

We are communicators, so therefore, in that sense, we are entertainers and

whether it’s tragic or happy, it is still entertainment. So it’s both. MH: In the sense that you’ve just said that I’ve

sung those things, I think yes. The word ‘unique’ means unique, and

I can’t imagine that another voice couldn’t be able to do it.

MH: In the sense that you’ve just said that I’ve

sung those things, I think yes. The word ‘unique’ means unique, and

I can’t imagine that another voice couldn’t be able to do it. MH: [Laughs] Exactly, poor guy. It was

very funny — I did that to myself last year.

I was rehearsing L’Italiana in Dallas

and I had the umbrella. We were having a good time, and where I sing

“No, no, no” and I slammed down the umbrella and stabbed my foot.

MH: [Laughs] Exactly, poor guy. It was

very funny — I did that to myself last year.

I was rehearsing L’Italiana in Dallas

and I had the umbrella. We were having a good time, and where I sing

“No, no, no” and I slammed down the umbrella and stabbed my foot.  MH: But it’s starting to pull back. Butterfly has really moved out of the

mainstream of the repertory, whereas Semiramide

has moved in. It’s not done everywhere, but you see Semiramide being done every season in

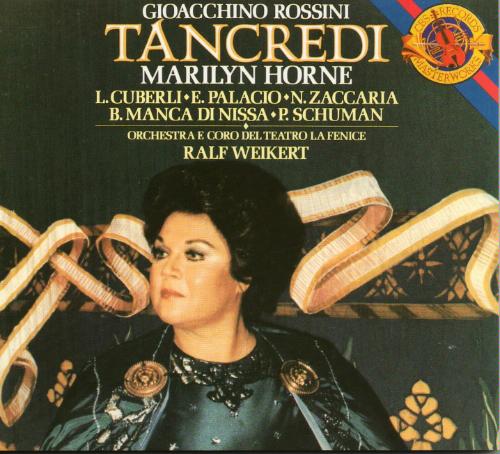

Europe or in the United States. That is a miracle. Tancredi is in; William Tell is back in. There

are lots of fascinating things like Julius

Caesar and other Handel operas. We now have the generations

of singers that have come after Sutherland and myself, after people who have

done this repertory. [See photo at right, and also my Interview with

Joan Sutherland and Richard Bonynge.] The kids have gone to school

and they’ve liked what they heard from us. They start to copy it, and

they start to say, “That’s what I want to do.” That’s how it’s gotten

started. I remember a friend of mine had just come from judging a contest,

and he said there were ten mezzo sopranos and seven of them sang “Iris

hence away” with few variations. [Both laugh]

MH: But it’s starting to pull back. Butterfly has really moved out of the

mainstream of the repertory, whereas Semiramide

has moved in. It’s not done everywhere, but you see Semiramide being done every season in

Europe or in the United States. That is a miracle. Tancredi is in; William Tell is back in. There

are lots of fascinating things like Julius

Caesar and other Handel operas. We now have the generations

of singers that have come after Sutherland and myself, after people who have

done this repertory. [See photo at right, and also my Interview with

Joan Sutherland and Richard Bonynge.] The kids have gone to school

and they’ve liked what they heard from us. They start to copy it, and

they start to say, “That’s what I want to do.” That’s how it’s gotten

started. I remember a friend of mine had just come from judging a contest,

and he said there were ten mezzo sopranos and seven of them sang “Iris

hence away” with few variations. [Both laugh] MH: Not always. I turned down doing a Handel

opera at the Met because I just can’t do that role in that house. The

role is too low, and it’s just too big a house. Those whoppers were

done in theaters that seat a thousand people or less!

MH: Not always. I turned down doing a Handel

opera at the Met because I just can’t do that role in that house. The

role is too low, and it’s just too big a house. Those whoppers were

done in theaters that seat a thousand people or less! BD: Oh, it’s lots of fun.

I’m able to design my own programs and put the music up there. In each

one of the programs for United I make sure that there’s a piece by an American

composer. I don’t use the term ‘American’

since that’s another carrier, but I will say it’s a

work by so-and-so from Toledo, or by the well-known New York composer.

They let me get away with that.

BD: Oh, it’s lots of fun.

I’m able to design my own programs and put the music up there. In each

one of the programs for United I make sure that there’s a piece by an American

composer. I don’t use the term ‘American’

since that’s another carrier, but I will say it’s a

work by so-and-so from Toledo, or by the well-known New York composer.

They let me get away with that. MH: A lot of the time it is; a lot of the time it’s

real hard drudgery. I’m having a great time doing Falstaff right now, so it’s really fun,

but I’ll be soon doing some things that are a lot more taxing vocally, like

Tancredi. You can have moments

when you’re having a lot of fun, but there are moments when you’re really

being nailed to the wall. [Both laugh]

MH: A lot of the time it is; a lot of the time it’s

real hard drudgery. I’m having a great time doing Falstaff right now, so it’s really fun,

but I’ll be soon doing some things that are a lot more taxing vocally, like

Tancredi. You can have moments

when you’re having a lot of fun, but there are moments when you’re really

being nailed to the wall. [Both laugh]| Marilyn Horne was born on January

16, 1934, to Berneice and Bentz Horne in Bradford, Pennsylvania. The Horne

household was always filled with music; Horne’s father was a semi-professional

singer and her mother sang and played piano. From an early age, Horne and

her sister Gloria performed for their family. Horne’s father began coaching

Marilyn when he realized her perfect pitch and two and half octave range.

She began formal vocal study at age five, and made her performing debut at

a Bradford political rally for Franklin D. Roosevelt’s presidential campaign,

singing “Believe Me, If All Those Endearing Young Charms.” When Horne was eleven, she and her family moved across the country to Long Beach, California. At the age of thirteen Horne began singing with the Los Angeles Concert Youth Choir, under the direction of Robert Wagner. The Youth Choir, later re-named the Roger Wagner Chorale, provided Horne with lasting friendships and career-boosting contacts. During her time with the Chorale, Horne met and befriended Franklin D. Roosevelt’s daughter. This connection provided Horne with the opportunity to sing in Herbert Stothart’s musical version of Roosevelt’s inaugural address, The Only Thing We Have to Fear. While still in high school, Horne began singing backup roles for Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer films such as Joan of Arc. Horne graduated from Long Beach Polytechnic and started studying music with William Vennard at the University of Southern California. During her time at USC, Horne had the chance to sing in a master class taught by the renowned Lotte Lehmann. Horne also met her future husband, Henry Lewis, while in college. Though they divorced in 1974, Horne and Lewis had a daughter together, Angela, in 1965. In 1954, at the age of twenty, Horne made her operatic debut with the Los Angeles Guild Opera in The Bartered Bride. That summer, Horne dubbed the singing voice of Carmen in the film Carmen Jones. In 1964, Horne made her debut at London’s Covent Garden. The next year, during the Ojai Festival, a classical music festival in Ojai, California, Horne was approached by Lotte Lehmann, who invited Horne to participate in performances at the Vienna Opera House. Horne was next asked to sing at the Gelsenkirchen Municipal Opera in Germany, where she remained for three years. After returning to the United States, Horne performed as Marie in Wozzeck and then as Mimi in La Bohème. The Metropolitan Opera, which has recently named Horne its first official legend, first hosted her onstage in Bellini’s Norma in 1970. Horne has received numerous other awards and remains one of the best singers ever to grace the stage. She has been in over 1,300 performances and, in 1999, achieved her personal goal of singing in every state. Among Horne’s notable awards is the Rossini Medaglia d’Oro, the first award given to her by the Rossini Foundation. She has also received the Commander of the Order of Arts, the Fidelio Gold Medal from the International Association of Arts Directors, and the Yale University Sanford Medal. Horne has honored by the Kennedy Center and has received four Grammy Awards: two for Best Classical Performance, one for Best Opera Recording, and one for Lifetime Achievement. Horne performed at President Clinton’s 1993 inauguration and has been honored by Presidents Clinton and George Bush, Sr. In 1994, Horne began the Marilyn Horne Foundation, one of the leading non-profit vocal arts organizations in the country. The Foundation, launched on Horne’s sixtieth birthday, seeks to encourage, support, and preserve the vocal recital. For the last six years, Horne has showcased the foundation’s work with a festival at Carnegie Hall entitled “The Song Continues.” According the Peter G. Davis of the New York Times, “Over the last 15 years the foundation has presented more than 100 young singers in recitals and educational programs across the country, reaching an audience of more than 100,000.” Horne’s last classical performance occurred in New York’s Carnegie Hall in 2000, but she continues to participate in programs that share her interest in American folk and popular music. In 2005, Horne was diagnosed with pancreatic cancer, but in January 2008 she went into remission. She credits music as a critical factor in her recovery: “For me, at least, nothing helped surviving chemotherapy quite as effectively as dozing off with an iPod playing nonstop in my ear.” She currently serves as the voice program director of the Music Academy of the West in Santa Barbara, California, a position she has held for over a decade. This biography was written by George Cunningham, Summer 2007; revised by Sarah DeSantis and Lindley Homol, Fall 2009. |

This interview was recorded at her apartment on November

15, 1988. Sections were used (along with recordings)

on WNIB twice in 1989, and again in 1990, 1992, 1994 and 1999.

A small section was also used on the website of Lyric Opera of Chicago as part of their

50th Anniversary Season which saluted several Jubilarians who were significant in the

history of the company. The full interview was transcribed and posted

on this website in 2012.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website, click here.

Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM, as well as on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio.

You are invited to visit his website for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.