A Conversation with Bruce Duffie

NZ: No. Opera is not dying, but certainly

we are in a time of vocal crisis. I don’t want to offend anybody, but

come up now with a perfect cast for Aïda.

Give me a perfect cast for Il Trovatore.

Give me one Norma!

NZ: No. Opera is not dying, but certainly

we are in a time of vocal crisis. I don’t want to offend anybody, but

come up now with a perfect cast for Aïda.

Give me a perfect cast for Il Trovatore.

Give me one Norma! BD: Can we not prevail on someone like you, with

your experience, to go into the studio and teach a few great, promising voices?

BD: Can we not prevail on someone like you, with

your experience, to go into the studio and teach a few great, promising voices? BD: Are the pirate records better than the commercial

records?

BD: Are the pirate records better than the commercial

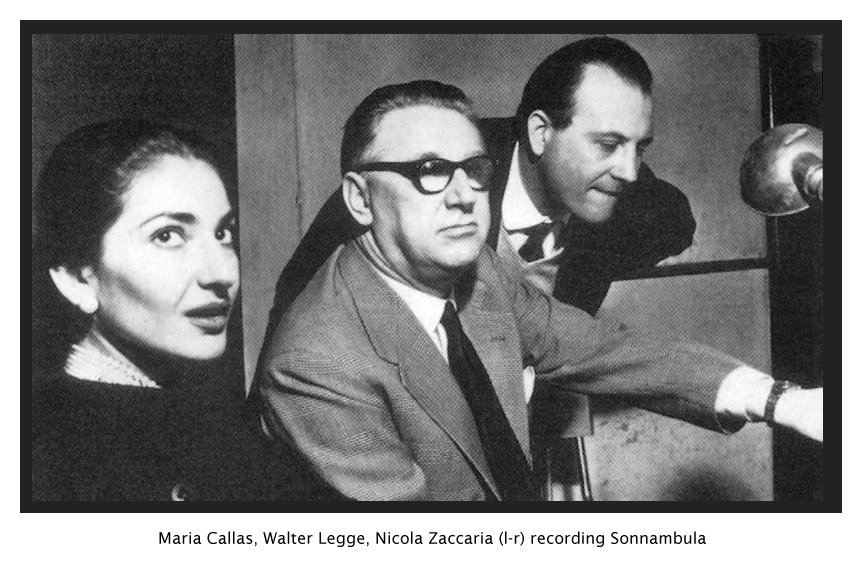

records? NZ: I have known Maria for a long time because we

were together in Greece way back. I am Greek as you know. Maria

Callas, of course, had a very strong personality. This personality

suited her very well in everything that she could do. Some people felt

antagonistic when faced with her personality, and so some hostility was created.

People were saying that she was not a nice person. Other people, who

adored her since then, today keep adoring her. It seems like today

there is a secret sect of people that keep adoring Callas — the famous widowers

of Maria.

NZ: I have known Maria for a long time because we

were together in Greece way back. I am Greek as you know. Maria

Callas, of course, had a very strong personality. This personality

suited her very well in everything that she could do. Some people felt

antagonistic when faced with her personality, and so some hostility was created.

People were saying that she was not a nice person. Other people, who

adored her since then, today keep adoring her. It seems like today

there is a secret sect of people that keep adoring Callas — the famous widowers

of Maria. NZ: Oh, no... leaving aside all the drugs and medications

and things, because singers go around with small piece of luggage full of

treatment for the voice. When one doesn’t feel well, one saves oneself

in certain parts so that he can give in those parts of the opera in which

the audience expects more or expects the big things.

NZ: Oh, no... leaving aside all the drugs and medications

and things, because singers go around with small piece of luggage full of

treatment for the voice. When one doesn’t feel well, one saves oneself

in certain parts so that he can give in those parts of the opera in which

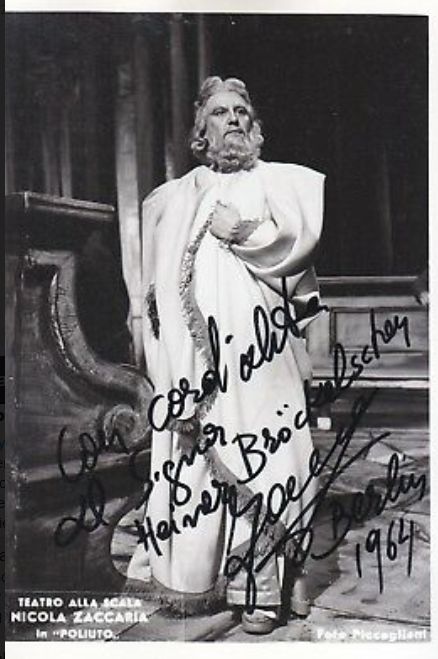

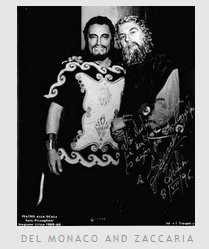

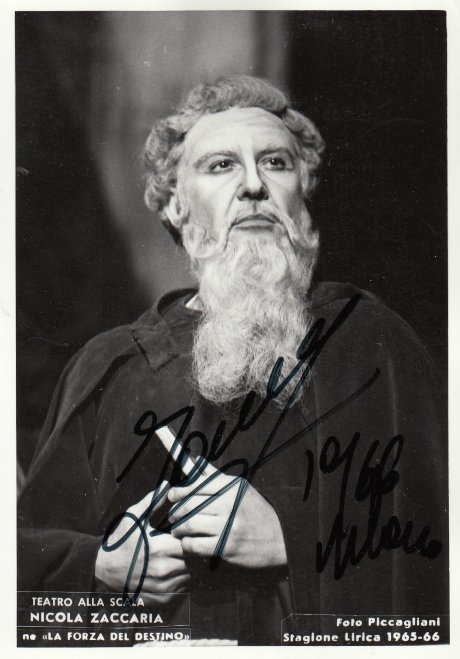

the audience expects more or expects the big things.[Obituary from The Independent] [Photo added for this website presentation] Nicolas Angelos Zachariou (Nicola Zaccaria), operatic and concert bass singer: born Athens 9 March 1923; twice married; died Athens 24 July 2007. The Greek bass Nicola Zaccaria, whose career took him all over Europe, sang for two decades at La Scala, Milan. During that period he was frequently in performances whose prima donna was Maria Callas and he also appeared with her at Covent Garden and in Dallas, where he made almost yearly visits. He also made many recordings with Callas. His repertory was mainly Italian and French, for which his resonant, smoothly produced and warm-toned voice was best suited. As his second wife he married the American mezzo Marilyn Horne, and sang in a number of operas in which she was the star.  He was born Nicolas Angelos Zachariou in Athens in 1923. He studied at the

Royal Conservatory there and made his début in Athens in 1949 as Raimondo

in Donizetti's Lucia di Lammermoor. His international career began as Nicola

Zaccaria in 1953 when he made his Scala début as Sparafucile in Verdi's

Rigoletto. He first sang with Callas in 1954 as the Oracle in Gluck's Alceste

and during the next couple of years appeared with her as the Soothsayer in

Spontini's La Vestale, Rodolfo in Bellini's La sonnambula (also given at

the Edinburgh Festival), Raimondo in Lucia and Oroveso in Bellini's Norma.

He made his Covent Garden début in 1957 as Oroveso (with Callas as

Norma) and his fine voice was greatly admired.

He was born Nicolas Angelos Zachariou in Athens in 1923. He studied at the

Royal Conservatory there and made his début in Athens in 1949 as Raimondo

in Donizetti's Lucia di Lammermoor. His international career began as Nicola

Zaccaria in 1953 when he made his Scala début as Sparafucile in Verdi's

Rigoletto. He first sang with Callas in 1954 as the Oracle in Gluck's Alceste

and during the next couple of years appeared with her as the Soothsayer in

Spontini's La Vestale, Rodolfo in Bellini's La sonnambula (also given at

the Edinburgh Festival), Raimondo in Lucia and Oroveso in Bellini's Norma.

He made his Covent Garden début in 1957 as Oroveso (with Callas as

Norma) and his fine voice was greatly admired.Zaccaria first sang at the Salzburg Festival in 1957 as Don Fernando in Fidelio and the Monk in Verdi's Don Carlos, followed in 1960 by the Commendatore in Don Giovanni and in 1962 by Ferrando in Il Trovatore. Meanwhile he created the Third Tempter in L'assassinio nella cattedrale, Pizzetti's adaptation of T.S. Eliot's play Murder in the Cathedral at La Scala in 1958. The following year he made his US début at Dallas as Creon in Cherubini's Medea, with Callas in the title role and Jon Vickers as Jason. This scored a tremendous success and the production, with Callas, Vickers and Zaccaria, was staged later in 1959 at Covent Garden, where it was received with equal praise. Zaccaria's roles at Dallas during the 1960s included Melisso in Handel's Alcina (with Joan Sutherland as Alcina), Palemon in Massenet's Thaïs, Colline in La Bohème, Banquo in Verdi's Macbeth, Rochefort in Donizetti's Anna Bolena and Cirillo in Giordano's Fedora. In Europe it was a particularly busy decade for the bass. In Vienna he sang Timur in Turandot (with Birgit Nilsson as Turandot), Arkel in Pelléas et Mélisande and, in 1962, King Philip II in the Italian version of Don Carlos. The following year he sang Philip in the French version at the Paris Opera (in French) and the Grand Inquisitor at Covent Garden in the same opera (in Italian). In Florence in 1962 Zaccaria sang the really villainous role of Caspar in Weber's Der Freischütz, but though his singing was praised he was found not malevolent enough. As Pimen in Mussorgsky's Boris Godunov in Turin, however, he received nothing but compliments. Count Walter in Verdi's Luisa Miller was another villain, but Arkel at Aix-en-Provence exuded kindliness, as did the Padre Guardiano in Verdi's La forza del destino at Salzburg in 1966. He sang Ramfis in Aida at Naples and Giustiniano in Donizetti's Belisario at Venice in 1970 and at Bergamo the following year, returning to Venice in 1972 for Stromminger, the heroine's father in Catalani's La Wally. At Dallas in 1974 Zaccaria sang Lothario in Thomas's Mignon, with Marilyn Horne as Mignon. In 1975 he took on the heavy role of King Mark in Wagner's Tristan und Isolde, apparently with some success. Rossini's Tancredi was mounted for Horne in 1977 in Rome and Houston, with Zaccaria as Orbazzano in both cities. He sang Astolfo in Vivaldi's Orlando at the Teatro Filarmonico in Verona, with Horne in the title role. In Rossini's La donna del lago at Houston in 1981, Horne sang Malcolm and Zaccaria was Douglas. Finally Tancredi was revived at Aix-en-Provence in 1981 and at Venice in 1982, with Horne and Zaccaria in their usual roles. -- Elizabeth Forbes

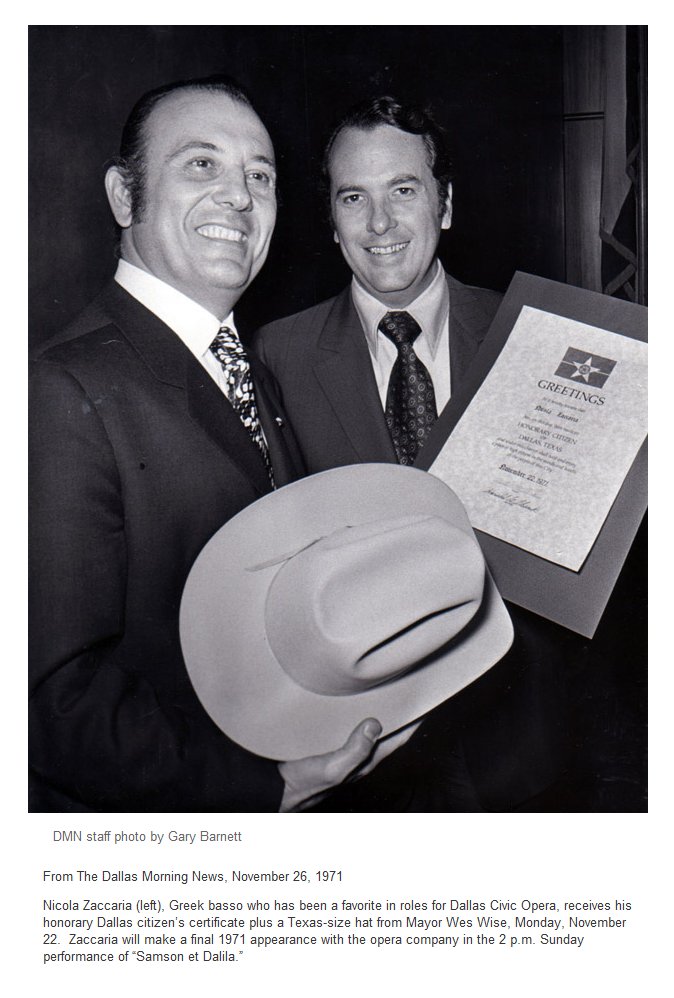

|

This interview was recorded in a dressing room of the Civic Opera

House in Chicago on November 16, 1988. The translation was provided

by Marina Vecci of Lyric Opera. Portions were used (with recordings)

on WNIB in 1990, 1993 and 1998. The transcription was made and posted

on this website early in 2013.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website, click here.

Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM.

You are invited to visit his website for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.