Microtonal Composer Ben

Johnston

A Conversation with Bruce Duffie

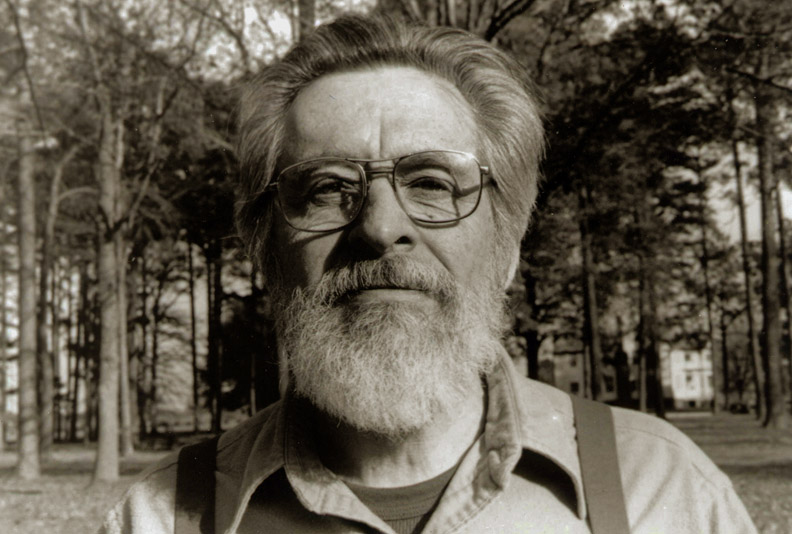

Ben Johnston was born in 1926 in

Macon, Georgia. He attended the College of William and Mary and

Cincinnati Conservatory, later studying with Harry Partch, Darius

Milhaud, and John Cage. Johnston taught composition and theory at the

University of Illinois from 1951 to 1983. Works include Quintet for

Groups, Sonnets of Desolation, Carmilla, Sonata for Microtonal Piano,

and Suite for Microtonal Piano, and ten string quartets to date. All

ten quartets will soon be released in a series of three recordings by

the Kepler Quartet (New World Recordings). Awards include a Guggenheim

Fellowship, a grant from the National Council on the Arts and the

Humanities, and two commissions from the Smithsonian Institute. In

2006, Johnston moved to Wisconsin in order to better care for his wife,

Betty Hall Johnston, who was seriously ill. Since her death in 2007, he

has continued to rehearse intensively with the Kepler Quartet. He is a

member of ASCAP and received the Deems Taylor Award in 2007. His

Quintet for Groups was awarded the SWR Orchestra prize at the 2008

Donaueschinger Musiktage.

|

Much contemporary music is difficult for many listeners to get into,

and in the Classical Music field, this problem is accentuated

multi-fold. Being on the cutting edge or just making explorations

will leave most of the public out in the cold, at least until the new

ideas have been demonstrated and digested. Doing this in the

brief space of a single concert — or

even a series of concerts — cannot begin to illuminate the

wonders and glories of new ideas, if indeed there are any to be found!

Add to all of this the wrenching change in musical language that comes

with microtones, and you have got perhaps the thorniest and most

difficult arena into which one can venture. My guest, Ben

Johnston, has done just that, so if he is not as well-known as others,

he is certainly an outstanding proponent of his discoveries and

creations.

His catalogue includes string quartets and other chamber pieces, as

well as larger works and items for re-tuned piano.

We had spoken a few times on the telephone, and finally found a

convenient time and place to get together for an interview. He

was in Chicago to give the keynote address at a symposium, so we took

the opportunity to meet before everything got going.

Bruce Duffie:

Tell me about writing microtonal music. Why

aren’t you satisfied with twelve tones?

Ben Johnston:

[Laughs] Actually, that wasn’t why I

started doing it. When I first started composing, I spent about

ten years not doing that. I was writing music as everybody else

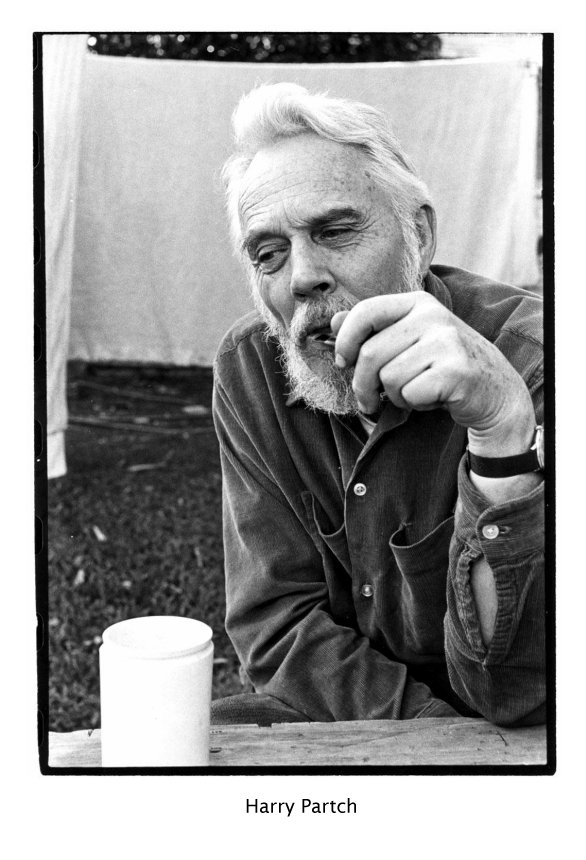

writes it, more or less. That was in the fifties. In 1949

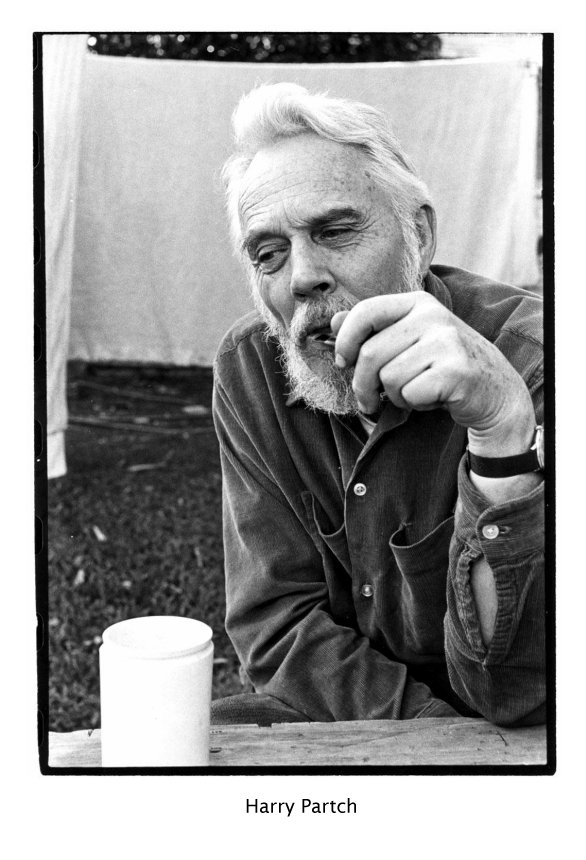

and ‘50 I went out to California and worked for six months with Harry

Partch [photo at right].

It was going to be a whole year, but he got ill

and closed up his studio. So I went to Mills and studied with

Milhaud for

the balance of the year. Then I got a job at the University

of Illinois, and within a few years we brought Partch there and did

some of his large works. I was involved very

heavily in the business end of the

production of The Bewitched,

but not in subsequent productions. That was atypical of me, and

they were sponsored not by music but by theater, and later by the

student groups. He was around in this area, including

Chicago. He was living in Evanston for a while and did a film

with Madeline Tourtelot during the late fifties or early sixties, but

he went back to California where he stayed

the rest of his life. This was a fruitful period for him,

being in this part of the country. I don’t think he liked it

terribly well; he likes the west, but it was fascinating to have him

around.

So all during that period I was exposed to something. The

reason I went to study with him was because a musicologist told me

— after we

had a discussion about how music theory wasn’t based on acoustics, and

I was objecting that it ought to be and that it wasn’t — he

said, “I have a book you should

read,” and gave me Genesis of a Music.

So I read it,

and then I wrote to the publisher and they forwarded the letter

— which

they won’t always do, but it was a friend of his. So she

forwarded the letter to him and we corresponded for a while. I

realized rather quickly that I couldn’t get very far without really

being there and hearing what was going on; that if I tried to do it

myself, I would probably come to grief, and I think I would have.

It’s just too difficult and too expensive, and too a lot of

things. So I went out there, and that was the beginning of my

active interest in that kind of thing. But as I suggested, I had

become fascinated by the fact that music wasn’t in tune. I got

that

first by just hearing that it wasn’t on the piano.

Ben Johnston:

[Laughs] Actually, that wasn’t why I

started doing it. When I first started composing, I spent about

ten years not doing that. I was writing music as everybody else

writes it, more or less. That was in the fifties. In 1949

and ‘50 I went out to California and worked for six months with Harry

Partch [photo at right].

It was going to be a whole year, but he got ill

and closed up his studio. So I went to Mills and studied with

Milhaud for

the balance of the year. Then I got a job at the University

of Illinois, and within a few years we brought Partch there and did

some of his large works. I was involved very

heavily in the business end of the

production of The Bewitched,

but not in subsequent productions. That was atypical of me, and

they were sponsored not by music but by theater, and later by the

student groups. He was around in this area, including

Chicago. He was living in Evanston for a while and did a film

with Madeline Tourtelot during the late fifties or early sixties, but

he went back to California where he stayed

the rest of his life. This was a fruitful period for him,

being in this part of the country. I don’t think he liked it

terribly well; he likes the west, but it was fascinating to have him

around.

So all during that period I was exposed to something. The

reason I went to study with him was because a musicologist told me

— after we

had a discussion about how music theory wasn’t based on acoustics, and

I was objecting that it ought to be and that it wasn’t — he

said, “I have a book you should

read,” and gave me Genesis of a Music.

So I read it,

and then I wrote to the publisher and they forwarded the letter

— which

they won’t always do, but it was a friend of his. So she

forwarded the letter to him and we corresponded for a while. I

realized rather quickly that I couldn’t get very far without really

being there and hearing what was going on; that if I tried to do it

myself, I would probably come to grief, and I think I would have.

It’s just too difficult and too expensive, and too a lot of

things. So I went out there, and that was the beginning of my

active interest in that kind of thing. But as I suggested, I had

become fascinated by the fact that music wasn’t in tune. I got

that

first by just hearing that it wasn’t on the piano.

BD: At that

point, were they were attempting

to be in tune?

BJ: Well, not

really. Temperament is what it

is; it’s a compromise. It’s a rather good compromise, but still,

if you listen closely, it’s just not. It

lacks something. I had heard choral singing — especially

madrigal-type choral singing and very good string quartet playing

— which is in tune, where people do take the trouble, and I

wanted

to know what the difference was. So I read up on it and I began

to be very dissatisfied with the way people were making

music. It was this question of being properly in

tune that got me into it, not the idea of a lot of notes, and

certainly not the idea of small intervals. When I began to

deal with Partch, he was using small intervals to represent the

inflections of speaking voice, the melodies of a spoken line.

BD: With the

rise and fall and everything?

BJ:

Everything was without any exaggeration, as it is when you set it to

recitative, or even to any kind of

traditional vocal setting. This naturalism interested me quite a

lot, not so

much because it was naturalistic, but because it was so precise.

And it did, indeed, sound the way he sounded when he spoke. He had put

his own vocal inflections into those melodies, and there they were

notated. This interested me quite a lot. I think that

probably my first fascination with microtones came about through that

particular application. I was not as interested in the

harmonies and the unusual scales that Partch was dealing with in a

purely musical sense. His approach to music was so alien to

me! I had a lot of respect for it, but it was really not

something that I would ever do.

BD: Did you

follow a whole new system of notation, or

did you use Partch’s notation?

BJ: I didn’t

use Partch’s notation because it is largely tablature. He tells

you what to do to

the instrument, not what’s going to sound. So if you don’t

know the instrument — which is almost impossible

since they’re privately

made and owned, and there’s only one of each — this

is just hopelessly

difficult to understand. So I thought, “No,

that is not a

solution.” I had to invent a notation, but

I didn’t do that

until well over ten years later. I started doing it after I had

established myself

well enough that people would take me seriously as a composer. At

first it was locally, at the University of Illinois, where

there were maybe three or four people — John

Garvey, who was at

that time the violist of the Whirlwind Quartet and the Director of the

Festival of Contemporary Arts; Claire Richards, who was a pianist;

and George Hunter, who was the leader of the Collegium Musicum. I

was fascinated by what George was doing because he was so careful

with the intonation. I was aware that what was happening was

exactly what I had been interested in, so there was sort of a

distant connection there. He was not at all interested in

applications I talked about making.

BD: Have you

got absolute pitch?

BJ: Yes, but

this doesn’t help. In fact, it

hinders. Absolute pitch is simply a very

good tonal memory, and if you are synched into it too well,

then you know where A is, and you’re impatient with any other A, which

in most music really not the case because, as you know, A moves.

BD: From

orchestra to orchestra it’ll

move.

BJ: Oh yeah,

and not only that, but within a piece. So it’s just not feasible

to do it

that way. I found

that I had absolute pitch in Partch’s system by the time I was through

working with him, so I could say, “That’s a 16/11 ratio.” I knew

that note, and what it did was to

focus me on a very, very careful cultivation of relative pitch. I

worked very hard during all that time with that sort of thing.

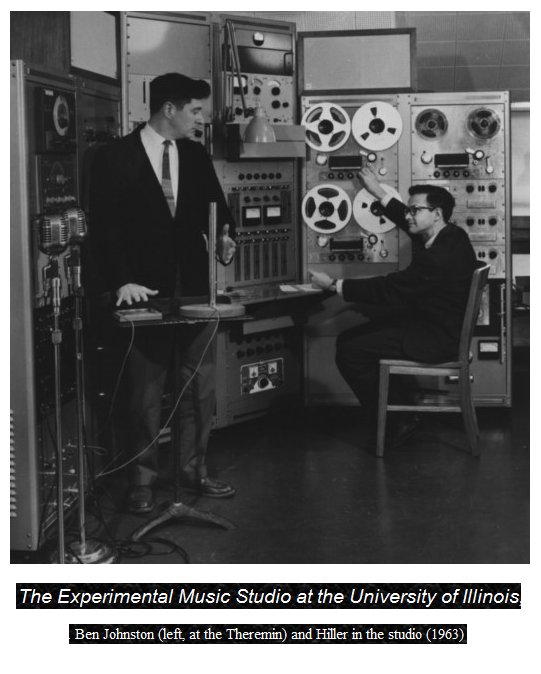

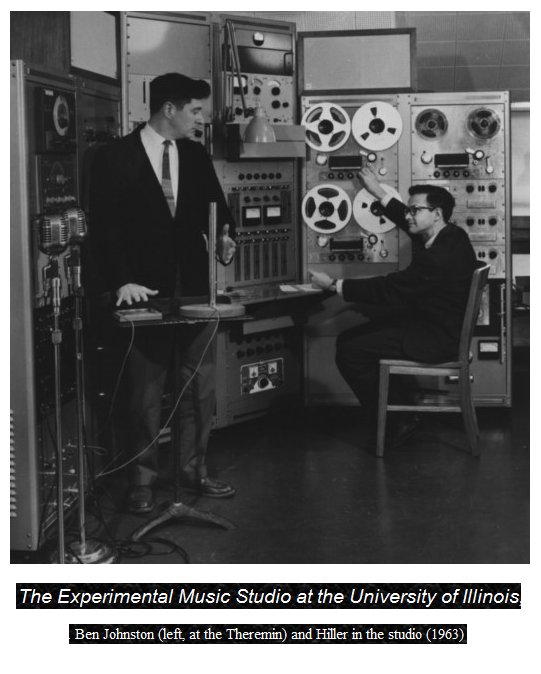

Then when I got into writing, my first idea was that I’d do it all

electronically, because Lejaren Hiller was just beginning to found the

University of Illinois Electronic Music Studio. There wasn’t one

anywhere in the United States then, not even Columbia-Princeton.

He started it down there. Columbia-Princeton got off

to a much bigger start than Hiller did because they had a lot of grant

money and he didn’t, but he actually did beat them to it. So I

thought that’s the way to do it.

BD: With

electronics, you had absolute control over everything?

BD: With

electronics, you had absolute control over everything?

BJ: Yeah, and

you don’t have to worry about training the players. I went to

Columbia-Princeton

the year before they opened. They let me do it because it was the

only year I had free, and it was a sabbatical year. I got a

Guggenheim Fellowship, and I found out within a week that I

couldn’t do what I wanted to do, because the instruments simply weren’t

subtle enough.

BD: You were

ahead of the technology then?

BJ:

Yeah. You need digital technology. I

could do it beautifully now on a computer.

BD: Would you

go back to it now?

BJ: Not

really, because I got so fascinated when I

was forced to do it. There are three possibilities.

You either build a whole set of new instruments, the way Partch did,

and

go that route. I knew what was involved in that and it terrified

me. I don’t have the right talents. So then I

thought about the electronic thing, and I discovered that technology

wasn’t equal to the task. The only thing left was to take

ordinary musicians and persuade them to do this, and somehow enable

them to do this. So I went that route. I got so fascinated

in

that problem that I never really wanted to go away from it. The

idea is finding people who understand what it is to play a

Mozart quartet and have it really sound in tune, and then extend

that. Extrapolate that and ask, “What is it to play

some much more complicated music really in tune? Exactly what

happens? Down to

fine points, what happens to the pitch?”

I began

analyzing things with that in mind. The first thing I did was to

re-tune a piano. I had an elaborately tuned piano with

eighty-one different notes on it — eighty-one different pitch

classes. There were only seven notes that had any

octave equivalent, and each of them had only one. So it was

really very hard to train my ear to

that.

BD: Did you

ever invite someone to sit down at this instrument and play some

Chopin?

BJ: Oh,

sure. That was a bad joke

from the beginning, but it was horrifying sounding to play

anything on it except just exactly what it was designed for. I

wrote the Microtonal Piano Sonata

for that during

that early period, and I wrote the Second

String Quartet.

BD: Is it

possible to play that microtonal sonata on

any other instrument than that specific one?

BJ: You can

take any

piano and re-tune it, but you can imagine how hard it is because

you don’t have any octaves. You’re tuning fifths and

thirds.

BD: You have

to tune every string, then, to a strobe?

BJ: That

would be one way. When the

recording was done in New York, they took very great pains and the

Scalatron people were involved. They had their tuner there and

they did it that way. But that was later. The piece was

written for Claire Richards, who was my piano

teacher. She was quite interested in what I was doing,

although she said she didn’t see why I did it. The idea of

writing a quartet came about because

I had written the First String

Quartet, which is a twelve-tone

piece. It was written for the Walden Quartet, Garvey being one of

the players. They played it in New York and the tape of it

was heard by the LaSalle Quartet. They liked it very much and

said they wanted to play it. I like their performance of

it better than the Walden. It was a very good

performance and they said, “We want you to write us a

piece.” After three years, the sonata was too oppressive to me

and I couldn’t get it done. So I stopped

and wrote the quartet in about a month. That Second String

Quartet was never played by them. They didn’t like

it. They

didn’t like what I was doing. They didn’t want to try to do

it.

They rejected the whole thing. Through

Salvatore Martirano, I was put in touch with the Composer’s

Quartet who did want to play it, and ultimately they are the ones who

recorded it. But that’s how this all got started.

BD: Are you

still working with

microtones?

BJ: Yes.

BD: Do you

think it’s still the way to go?

BJ: It’s the

way I want to go. I still

think that music sounds better when it’s played in tune.

BD: Your

tuning or

anyone else’s?

BJ: I’m really not

much interested for myself. I would never do what Easley

Blackwood has done. [See my Interview with Easley

Blackwood.] What

Easley does is to take all the different possibilities of temperament,

any number of notes up to fifty or even beyond. But he’s got some

pieces that

do explore the possibilities of all those different temperaments.

To me, they’re all out of tune. I’m not particularly enamored of

it, although

I can enjoy out-of-tune music. It’s like

anything else, like listening to the prepared piano, which is not a

normal piano. It’s different every time you do it because every

piano is different, and every screw is different, for heaven’s

sakes! Introducing indeterminacy like that doesn’t disturb

me, but I’m not interested in it intellectually, and I do feel that it

doesn’t have as much emotional power as really

in-tune music, because that’s what happens. When those vibrations

are exactly synched, the expressive potential of whatever it is you’ve

got in the music is heightened greatly, and that is very

interesting to me. I have gotten to where I count on that, and I

don’t like the idea of

writing other music. I have done other things, such as

when LaMaMa, E.T.C., the off-off Broadway Company — Ellen

Stewart’s group — wanted a piece. They

commissioned me, and I knew there was no point in writing a micro-tonal

or a re-tuned anything for them.

BJ: I’m really not

much interested for myself. I would never do what Easley

Blackwood has done. [See my Interview with Easley

Blackwood.] What

Easley does is to take all the different possibilities of temperament,

any number of notes up to fifty or even beyond. But he’s got some

pieces that

do explore the possibilities of all those different temperaments.

To me, they’re all out of tune. I’m not particularly enamored of

it, although

I can enjoy out-of-tune music. It’s like

anything else, like listening to the prepared piano, which is not a

normal piano. It’s different every time you do it because every

piano is different, and every screw is different, for heaven’s

sakes! Introducing indeterminacy like that doesn’t disturb

me, but I’m not interested in it intellectually, and I do feel that it

doesn’t have as much emotional power as really

in-tune music, because that’s what happens. When those vibrations

are exactly synched, the expressive potential of whatever it is you’ve

got in the music is heightened greatly, and that is very

interesting to me. I have gotten to where I count on that, and I

don’t like the idea of

writing other music. I have done other things, such as

when LaMaMa, E.T.C., the off-off Broadway Company — Ellen

Stewart’s group — wanted a piece. They

commissioned me, and I knew there was no point in writing a micro-tonal

or a re-tuned anything for them.

BD: Just very

conventional stuff?

BJ: Yeah, I

would have to. So that was a very

different thing, and I like the piece. It turned out well.

It’s recorded, and it’s called Carmilla.

BD: When you

write some music, what do you expect of the

audience that comes to hear either an old piece or a new piece?

BJ: I don’t

care whether they know that there’s

anything funny about the tuning, and often they don’t. Most

people listening to String Quartet #4,

which is the one the Kronos

Quartet played here recently, don’t know that there’s anything odd

about that piece. You would have to look at the score to see,

because it sounds in tune and that’s all there is to it. There’s

some blues inflections, and they’re not done by the seat of your pants,

so to speak; they’re notated. What I did was to figure out what

blues

artists were doing. It involves the seventh partial

relationships, which apparently were there all along in African folk

music. That’s probably where it came from, and got into

American blues that way. It’s a very characteristic

sound, so I used that and people are aware of that, but it’s not

any more so than half a dozen other composers you could name, including

Gershwin.

BD: Then are

you a creator or a

reflector?

BJ: I don’t

care. It doesn’t seem very important to me. Insofar as I

have used eclectic style

content, it’s been in order to prove how different each of those things

sounds when it’s treated this way — which is a

rather different

motivation from what one usually has. For example, during the

fifties, under the influence of Milhaud — who

was after all my teacher — I was writing

neoclassic music like a lot of people were, a

lot like Stravinsky in many cases. That music had a sort of

double intention. It was to reflect the past, and at

the same time, the present. Later I came back to some of those

intentions, especially in the Suite,

which is the piece they’re going

to play at ASUC [American Society of University Composers] this

year. That

is a piece which is deliberately very eclectic, and it’s very

neoclassic. The last movement is a sort of homage to

Milhaud. It’s very Milhaud, but with a difference

because this thing is tuned to the overtones between the 16th and the

32nd partial. So an octave is twelve of those partials, rather

than a

normal octave. It’s very strange if you play it, like if you

tried to play Bach on it or anything like that. On the other

hand, composing for it I can make it sound extremely normal, which

most of the piece does. Yet every now and then, something

very strange happens. I’ve got a blues movement in that, too,

because some of the relationships are available and also sound like

blues. This is a kind of scatter-shot way of getting at the whole

thing,

but to try to really center on what you asked me, I feel that what I’m

doing in one aspect is trying to prove the worth of a new

discovery. It’s not a new discovery, it’s really an

old discovery. It’s like saying people used to grow food

this way, and it’s better than the way we’ve been doing it.

People used to tune music this way, and it’s better. If you

build on that, you can get something which is very much more

contemporary-sounding than all the twelve-tone music you could ask

for. It’s much more dissonant than anything that any of these

hyper-dissonant composers ever wrote, if you want it to be.

BD: Are you

going for dissonance?

BJ:

Occasionally. The middle movement of the Suite is called Etude

and it sounds like Iannis Xenakis. [See my Interview wih Iannis

Xenakis.]

It’s

hyper-dissonant, but it is a twelve-tone piece,

which Xenakis is not. He doesn’t write twelve-tone. It

is certainly atonal. It’s an atonal treatment of those partials,

and it’s a lot more dissonant than an atonal treatment of the twelve

notes we usually use. As Partch said, “Not only

consonance, but also dissonance is heightened,” and people forget

that. So I can do very

dissonant stuff as I please.

BD: Coming

back to my question,

then, what do you expect of the audience?

BJ: I like

them to respond with a powerful, affective

reaction to what I’ve done. That isn’t asking something of

them, that’s asking something of me — that I

should produce that

reaction in the audience. I also want them to accept the music

readily, but the more they listen to it, I would want it to be more

interesting. A lot of effort goes into what has

traditionally been called the art that conceals art, the effort to make

it extremely complex but to sound extremely simple. String

Quartet #4 is a good example of that, but it’s actually an

extremely

complex piece. There is an analysis of it in Perspectives of

New Music that’ll curl your hair, but the piece is immediately

accessible. It sounds like Aaron Copland; you can

get to it instantly, and that combination pleases me. That

complexity underneath means the more you listen to

it, the more there is to find. It’s like the difference between

reading a murder mystery by no matter who, and reading Crime and

Punishment.

BD: Do you

always strive to write Crime and

Punishment?

BJ: Yeah, if

possible.

BD: Is there

any entertainment in your music at all?

BJ:

Yeah. Sure.

BD: Where is

the balance, then, between the artistic

creation and the entertaining creation?

BJ: I don’t

find that there’s any need to make that

distinction. For example, in writing Carmilla, which

is a rock opera — it isn’t really a rock opera, but it’s the nearest I

could get to one, not knowing anything at all about

rock music — but it is deliberately playing upon

people’s most

vulnerable musical taste. It ingratiates itself with you, and

it does this in order to get hold of your guts and squeeze and wrench

because it’s a very violent story about

vampires. It takes the idea very seriously, so that you begin

to get the feeling that this is really about some kind of sex

perversion, and it’s very unsettling. The whole point there is to

do what the

vampire does — to seduce, not rape. This

approach, without the

melodrama, which of course that is, is ingredient in just about

everything I do. The idea is to get to people, in order to say

something that I want to say, whatever that is. Sometimes

it’s totally nonverbal. I really couldn’t tell you what I said,

but I do know that I wanted to say it, and that it is

different from anything else I ever tried to say or, for that

matter, different than anybody else that I also look at musically.

*

* *

* *

BD: How has

what you’re trying to say

changed in the last ten, fifteen, twenty, thirty years?

BJ: In about 1970 a

lot of things

happened. I had a very big health crisis, which I needn’t go into

in detail, but it was very frightening and it turned out well. I

didn’t suddenly discover that I was dying or

something like that, but it was as bad as that, and it really

frightened me. I really didn’t know for a year or for a

couple of years whether I would make it through or not. During

the time I was writing Carmilla,

which may be

one reason that’s such a bitter piece. That experience threw me

back on religion, which I had let drop,

and having re-discovered that, I found I was much happier. It

isn’t a matter of comfort, but a matter of responsibility. It’s

like having felt that I had been evading a kind of responsibility for a

long time, and that it was time I quit evading that. So

my whole style, everything I wanted to do, changed. I wanted to

stop writing music that was accessible only to other composers and

specialized concerts of “new music.” I wanted to write for more

people than that, and more ordinary people. I wanted to write

music my wife would like. I wanted to write music that people

that

I knew would never go to those new music concerts, would nevertheless

like. And yet, I wanted to interest the people that I had already

been trying to interest, who were going to those new music concerts,

and whose whole focus was around that sort of thing. So with that

double intention, it sent me into asking how I could make

the work so complicated that it will be interesting, and yet so simple

that it will be immediately accessible. I found I was trying

to write a very different kind of music. The Mass was one of the first pieces I

wrote in that

way, a little choral piece, which was a setting of a poem my daughter

wrote. What I was doing

was trying to write music that was instantly reachable, but which was

quite different from anything that people had ever heard,

but in a subtle way so that when they really began to get into it,

there was a difference between it and other things. They wouldn’t

necessarily understand this, but which is nevertheless very

perceptible, and it was the intonation that enabled me to do

that. In order to make sure that it would work, what I did

was to bring in the higher partials. I had been dealing up to

that point in what Partch called “five-limit,”

that is to say, no

prime numbers of overtones over the fifth partial, one-three-five,

which actually does refer to the triad, although

what we call the third is the fifth, and what we call the fifth is the

third, in terms of the partials. You can develop triads so that

you get eighty-one notes per octave. That eighty-one happens to

be what

I did on that piano, but fifty-three and sixty-five in the quartet, and

just any number of notes that you happen to want. You’re

still not using anything new harmonically; it’s

all based on the same intervals that everybody already knew. You

can see why I did that. To ask people to deal with

intervals that they don’t already know is much harder. If they’re

dealing with just simply pure versions

of the intervals that they are already very familiar with, the task is

easier. I thought that, but in fact it’s much harder because

people are

used to playing fast and loose with those intervals, and it’s very hard

to get them out of that habit. Whereas if they think they’ve got

to play something they know they never heard before, and yet it has to

sound in tune, they actually rise to the occasion a little

better. I was bringing in the seventh and eleventh partials — not

all at once, but bit by bit, bringing me up to the level of

complexity about where Harry Partch was.

BJ: In about 1970 a

lot of things

happened. I had a very big health crisis, which I needn’t go into

in detail, but it was very frightening and it turned out well. I

didn’t suddenly discover that I was dying or

something like that, but it was as bad as that, and it really

frightened me. I really didn’t know for a year or for a

couple of years whether I would make it through or not. During

the time I was writing Carmilla,

which may be

one reason that’s such a bitter piece. That experience threw me

back on religion, which I had let drop,

and having re-discovered that, I found I was much happier. It

isn’t a matter of comfort, but a matter of responsibility. It’s

like having felt that I had been evading a kind of responsibility for a

long time, and that it was time I quit evading that. So

my whole style, everything I wanted to do, changed. I wanted to

stop writing music that was accessible only to other composers and

specialized concerts of “new music.” I wanted to write for more

people than that, and more ordinary people. I wanted to write

music my wife would like. I wanted to write music that people

that

I knew would never go to those new music concerts, would nevertheless

like. And yet, I wanted to interest the people that I had already

been trying to interest, who were going to those new music concerts,

and whose whole focus was around that sort of thing. So with that

double intention, it sent me into asking how I could make

the work so complicated that it will be interesting, and yet so simple

that it will be immediately accessible. I found I was trying

to write a very different kind of music. The Mass was one of the first pieces I

wrote in that

way, a little choral piece, which was a setting of a poem my daughter

wrote. What I was doing

was trying to write music that was instantly reachable, but which was

quite different from anything that people had ever heard,

but in a subtle way so that when they really began to get into it,

there was a difference between it and other things. They wouldn’t

necessarily understand this, but which is nevertheless very

perceptible, and it was the intonation that enabled me to do

that. In order to make sure that it would work, what I did

was to bring in the higher partials. I had been dealing up to

that point in what Partch called “five-limit,”

that is to say, no

prime numbers of overtones over the fifth partial, one-three-five,

which actually does refer to the triad, although

what we call the third is the fifth, and what we call the fifth is the

third, in terms of the partials. You can develop triads so that

you get eighty-one notes per octave. That eighty-one happens to

be what

I did on that piano, but fifty-three and sixty-five in the quartet, and

just any number of notes that you happen to want. You’re

still not using anything new harmonically; it’s

all based on the same intervals that everybody already knew. You

can see why I did that. To ask people to deal with

intervals that they don’t already know is much harder. If they’re

dealing with just simply pure versions

of the intervals that they are already very familiar with, the task is

easier. I thought that, but in fact it’s much harder because

people are

used to playing fast and loose with those intervals, and it’s very hard

to get them out of that habit. Whereas if they think they’ve got

to play something they know they never heard before, and yet it has to

sound in tune, they actually rise to the occasion a little

better. I was bringing in the seventh and eleventh partials — not

all at once, but bit by bit, bringing me up to the level of

complexity about where Harry Partch was.

BD: It sounds

like you’re taking all of

the performer-inspiration out of it, and making them rely exactly on

these precise intervals and precise notations.

BJ: Well yes,

but what happens is that I’ve got a very much closer approximation to

this ideal that you want

to always suggest to people. Then they can realize it how they

will, and it’s amazing how much more subtle that people can

be, and how they will get nuances. I would

particularly think that the two string quartets, #5 and #6, would interest you in that way,

because both of those

groups really get hold of those intonation problems and do

something with it. It goes way beyond what I knew it would

be! It isn’t different from what I knew it would be, it’s

just more so. It’s as if they got my vision, and being

players,

they were able to do more with it than I could! This is what you

always want.

BD: So then

despite this exactness of notation,

you’re expecting more out of the score each time it’s played?

BJ: Which

sounds just cruel, but in fact, it’s really very good. There’s

rather an interesting discussion of

Knocking Piece. Roger

Reynolds got interested in that piece, and

when he wrote his book Mind Models,

he discussed it briefly, and what he says it does is to push

thresholds. [See my Interview with Roger

Reynolds.] It pushes on thresholds of ability, and because it

does that, it stimulates a person to play right at the tip of his

ability, which of course is what any great performer always wants to

do. This almost guarantees that because you’re working so

hard to get those things right, and when you get them right, it feels

just

marvelous and there’s a kind of an exhilaration that happens!

George Hunter said that about the

un-notated, intonational problems of fourteenth and fifteenth century

music. When they rehearse Machaut or Dufay, they would sit and

listen to these things until they suddenly

found it just slipped into the right intonation, and then they would

just savor it. It’s just beautiful that way; the whole thing was

a kind of slightly ecstatic experience of getting

the whole thing to have that glow about it. That’s a very

romantic way of describing it, but it works. It

feels more like what the performer is actually experiencing to talk

about it that way. Hunter was the first person to point that out

to

me. It was, indeed, an emotional reaction that

you sort of knew. When I heard Indian performers play for the

first time live, it was in somebody’s home, so there was

a time to sit down and talk with them. I was asking about the

significance of the ragas and what they meant, and why they were played

at a certain time of day and what it meant. I also asked

why there were spring ragas and fall ragas,

and how that worked. They were explaining that Rasa, which

is their term for emotional content, was what the player

memorized, not the raga. He memorized the emotional content and

the raga was right when it expressed that precisely. It’s just

backwards from what we think

about. If we get it right, it will have the

right emotional content.

BD: You’re

saying put the emotion first?

BJ: Play

Beethoven right and it will move everybody. But they go the other

way around. If you

move everybody, then you must be playing it right. [Both

laugh] And that was, again, a lesson. It’s turned

my head around to think differently.

BD: Have you

basically been pleased with the

performances you’ve heard of your works?

BJ: What I’ve

done is gotten

into an area that frightens off people that aren’t good enough, so

I don’t very often have bad performances. I have no performance

or I have a good one. That’s one of the things that happens

when you notate everything this precisely, and it’s one of the

things that happens when you’re dealing with ear training. You’re

asking people to extend their ear training, and go on and

do things that they never thought they learned how to do. It’s

willy-nilly what I’ve had to

have, but yes, I think I’m very pleased. It took me

ten years to gain enough respect to be able to deal with those

performers that they would even look at my music! It might have

taken me longer than that, except for having certain people really push

what I did. I am better-known than I have any right to be,

considering how seldom my music is performed. I think that’s

because people remember

it. It’s different enough that it sticks in their minds.

I’m not sure that’s really what it is that makes

them remember it, but apparently they do. It’s interesting.

I have heard that said about Schoenberg, that his reputation

is out of all proportion to the number of times people have heard his

music. It’s true, but it’s that good! It

may be ever so forbidding, but it’s just very good, and when you get

into it, you have a kind of an experience that you don’t forget

readily. So consequently, without being performed very much, he

can remain one of the most important composers of our era. I

think he may never be performed very much because it’s

extremely hard to do it really well!

BD: Do you

think there will ever come a time when your

music will be easy?

BJ: I don’t

know. It’s getting easier; there’s

no question about that. I’ve had that experience that you hear

described so much, people telling Tchaikovsky that the Second Piano Concerto was

impossible, and that no one would ever be able to play it. [Both

laugh] Now everybody plays it. I mean,

literally everybody. It’s one of the things you have to play.

I’ve had that experience with Knocking

Piece. The people who

played it at first said, “We can’t play the whole piece. We’re

going to have to make a cut. We can’t stand it. The concentration

effort is too great and we just can’t.” So I said, “Well all

right, do what you can.” So they did what they could, but the

next time it was played, they played it all! It gets easier

and easier and easier, and now I hear theory classes learning bits of

it. You pose a problem, and if it’s a reasonable

problem and people solve it, then it gets into the pedagogy,

and it’s easy to communicate to other people how you do it. This

happens with the intonation. Even for

groups that have only heard one example of that kind of

thing, apparently most of them grasp it right away. I

have seldom ever had to go to a group and really work them hard to

begin with. What usually happens is that they take it and they

work on it for a long time, and then they bring me in and I tell them

what’s wrong. There usually isn’t a lot wrong. Certain

things do happen. For instance, there were going to be

three performances, not one, on this ASUC Series. I’m the

keynote speaker and they were going to do that as a gesture. But

two

of them fell through because there’s a lot of music being

played, and to undertake things that are that hard is very difficult to

do.

BD: As a

general rule, would you rather have your

piece played on an all-contemporary concert or would you rather have it

be in the middle of a mixed concert?

BJ: The

second; I would much rather. For one thing, I

think that generally all new-music concerts are terribly fatiguing to

the listener, and you fight that no matter what your piece

is and no matter where on the program your piece is. If it’s

first,

the audience isn’t warmed up; if it’s anywhere else, there is no

telling

what it came after. It’s just difficult for the audience, so that

no matter what the piece is like, it is in trouble to be in that kind

of setting. That’s one reason I wanted not out of those

concerts forever; I wanted at least to write music that wouldn’t be

thought of as only suitable in those concerts. That’s what’s

happened with the string quartets, and most of the

piano music. Virginia Gaburo, who plays both

of the big microtonal piano pieces — the Sonata and

the Suite — has

programmed them generally with quite different

music. She has to have an extra piano, one that’s tuned specially

for that, but she said that it certainly works much better

than to have it on a new-music program. On the record it’s with

Cage and Nancarrow, as

odd ways to use the piano. [See my Interview with John Cage,

and my Interview

with

Conlon Nancarrow.] That is what they focused on.

*

* *

* *

BD: In your

opinion, where is music going

today?

BJ: That’s very

hard to answer. I

certainly don’t think it’s going where people thought it was going

fifty years ago, but I’d like to think that what’s happening

is a humanizing of music, or re-humanizing of music. It got

terribly de-humanized in the face of the twentieth century, and I think

that the greater composers are exceptions. They’re not inhuman

like that, but if you start listening to all the rest of it, then you

see that an awful lot of it had its... I don’t know what happened

exactly,

but there’s something very strange about the emotional content, for one

thing. People seem to be primarily concerned either with

intellectual constructs, or with hyper-emotional states, like abnormal

or

insane states. All this stems from people like Berg

with the two operas which deal a lot with abnormal psychology, or

Schoenberg with the Pierrot Lunaire.

I’m sure it all

stems from that, but it also stems from the feeling of alienation,

and all those things that people talk about in contemporary psychology.

BJ: That’s very

hard to answer. I

certainly don’t think it’s going where people thought it was going

fifty years ago, but I’d like to think that what’s happening

is a humanizing of music, or re-humanizing of music. It got

terribly de-humanized in the face of the twentieth century, and I think

that the greater composers are exceptions. They’re not inhuman

like that, but if you start listening to all the rest of it, then you

see that an awful lot of it had its... I don’t know what happened

exactly,

but there’s something very strange about the emotional content, for one

thing. People seem to be primarily concerned either with

intellectual constructs, or with hyper-emotional states, like abnormal

or

insane states. All this stems from people like Berg

with the two operas which deal a lot with abnormal psychology, or

Schoenberg with the Pierrot Lunaire.

I’m sure it all

stems from that, but it also stems from the feeling of alienation,

and all those things that people talk about in contemporary psychology.

BD: Are we’re

getting away from this now?

BJ: I hope we

are. I think maybe we are. Maybe what is happening is that

the complexity of

contemporary life has knocked down to a kind of simple phase in terms

of how people begin to experience it. With computers and with

TV and a lot of the things that we take for granted as technological

main pillars of what we do nowadays, life actually gets

simpler on account of those things. On the one hand it is getting

more complicated, but it’s a lot easier to cope with it, and I think

that part of that has actually relaxed people somewhat. There’s a

movement that I sense to

rediscover the importance of the interior life as people traditionally

have described it. You see it a lot in people

who are overtly religious and give more attention to things like

meditation and

contemplation, and less attention to the more

external aspects. I think that this inwardness is helping

to correct a lot of the stresses in early twentieth

century music. It’s

been a violent period, Lord knows, and it reflects the external

world, I guess.

BD: Are you

then optimistic about the future of music?

BJ: I don’t

know whether to be or not. I feel

good about what I’ve been able to do, because I feel that if people go

in that direction at all, it will enable them to be complex in a way

that’s understandable. I know they need to be complex because

it’s clear. We’ve got a very complicated world that we live

in; you cannot be simple-minded about it and live. So we’re

stuck with the complexity,

but does it have to make us neurotic? Maybe not.

[Laughs] There’s a kind of analog between how to

deal with complex relationships sanely, and how to deal with complex

pitch relationships and still be in tune, so that it really does sound

complex and nobody would think it was Mozart again — not

that that would be bad, but anything again is not so

good. We are finding how to be as simple in our way as he was in

his way.

BD: You say “anything

again is not so good.”

Even going to another performance of the same work is not so good?

BJ: No,

another performance of the

same work is going to be new in some sense or it isn’t any good.

If it is just a carbon copy, then it will be dull, and I think that’s

what’s wrong with getting your favorite record out and playing it

again — which I don’t do anymore, or very

little. I found that I

wore out certain pieces so that I didn’t hear them anymore.

BD: You wore

them out in your ear?

BJ:

Yes. I heard them too much. I heard exactly the

same performance over and over again! A little groove is

worn in my ear, so that I know exactly what’s going to happen every

second, and it’s not good! Of course it’s a lot better if it’s a

superb performance to begin with, because that means that you have not

discovered everything in it on one or two listenings. Then it’ll

take you maybe fifteen or twenty listenings to get out of it what was

put

in to begin with. But that’s a great performance. Some of

them are, some of them aren’t, you know. [Both laugh]

BD: Are there

perhaps too many young composers coming along today?

BJ: There are

an awful lot, and I think

it’s like everything else — there’s just too much of everything.

One learns how to cope with that, and one of the ways is to turn it

off, which I think to everybody’s unhappiness is what has been done to

the majority of contemporary composers. People are just turning

them off almost before they had a chance to get started,

which is a damned shame because there are a lot of babies being thrown

out in that bathwater. But if you really are different in an

interesting way, then I think there’s a good chance people will notice

because there are too many people who aren’t, and the contrast is

fairly obvious after a while. The problem is

worse than it probably was once, but it’s the same, it’s not a

different kind of problem. I’m sure in the eighteenth

century in Europe, that to be a successful Kapellmeister was much more

likely than to be a Bach. There were a lot of those, and I

suppose too many, maybe.

*

* *

* *

BD: There is

a

work in your catalogue listed as being a chamber opera. Would you

tell me about it?

BJ: There are

two. There’s Carmilla,

which is the rock opera, and Gertrude,

a neo-classic

piece. Both of them were written with Wilford Leach. Leach

is the director of New York productions of The Mystery of Edwin Drood and of The Pirates of

Penzance, so he’s better known for

that. He’s a very interesting

playwright and I’ve known him since we were in college together.

He’s the one I always ask to work with if I can. He’s too

busy now, I guess, but the last thing we worked on was Carmilla,

and Gertrude was the thing

before that. Gertrude

is a

spoof, in a way. He did his thesis on Gertrude Stein, so in a way

it’s about Gertrude Stein, but it isn’t, exactly. It’s a

commentary on the legend of Gertrude

Stein and Isadora Duncan and Ernest Hemmingway and a lot of the

American ex-patriots. So it’s like a very ‘in’ joke, and the

whole thing is essentially funny. It takes just a few

players, but what’s hard about it is that the players, ideally, if

you wanted to do it absolutely well, should be mime dancers and able to

sing and act — all those things.

BD: That’s

asking an awful lot!

BJ: Yes, it

is. Consequently, the way we’ve

always done it is to have surrogate performers like Brecht. You

just sit them beside each other,

and when dance is called for, the dancer gets up and does it.

When singing is called for, the singer gets up and does it, and

when straight acting is called for, somebody else gets up and does it.

BD: All being

the same character?

BJ: Yeah,

which is okay. You can do

that by costuming them all the same way, and doing a few other things

like

that. It’s a detachment that’s required in order to get that

done, but with a kind of ironic text, it’s ideal.

BD: Are there

any other operas still in your mind?

BJ: No.

It’s so hard for people who

have to do a lot already — be on stage, memorize

the whole

role, act and all the rest — to worry about the

intonation as much as I

demand. So I haven’t tried to make that happen. The only

person I

know who has is Alois Hába in the opera, The Mother, where it is

quarter tones, eighth tones, sixth tones, etc. I’m not sure

what he used, but there are very elaborate tonal systems.

Apparently it was very successful, but I’ve never

seen it.

BD: When

you’re presented with a number of

commissions, how do you decide which ones you’ll accept and which ones

you’ll decline?

BJ: I don’t get

that many so I usually

accept them. Well, actually, I don’t. Sometimes

people ask me to write pieces and I

just can’t find that I know what to write for them, so I end up not

doing it; or I try and I don’t like it, so I never give it to

them. But other times, somebody asks me to do

something, and I do find the right thing to do. So I go ahead

and do it, and I didn’t even expect to write that piece. I hadn’t

been thinking about it or anything else, but for

some reason something worked. It’s very hard to explain exactly

why that happens. I’m writing a cello piece for Laurien

Laufman. I hadn’t planned

to write a cello piece and I didn’t particularly want to, but I got

an idea that suited and I liked the way she played. So I just

wrote this piece very quickly and it worked fine. The other

one that I can think of is a piece I did for Richard Rood, a violinist

in a string quartet for New Music of

America when it was in Chicago. They played one of my

quartets and he liked it, so he said, “I have a group that is a

trio with a clarinet. I’m the violinist and there’s a

cellist. We have a

pianist, but you probably would want to use the trio,

because we don’t want to re-tune the piano.” So I said, “All

right, I’ll write

you a piece.” I had wanted to write a piece involving a

woodwind with strings, and that suited me very well. It’s a very

light piece and not very long, but it’s pleasant. So there’s one

that I just did without knowing

that I wanted to do it. Ward Swingle commissioned a

piece for the Swingle Singers. I had done them one at his request

earlier and he didn’t like it. What I did in that case was to do

a big band jazz piece for them with microtones. They said the

microtones made it

so hard that they couldn’t put it on their pops concerts, but they

didn’t want to put it on another kind of concert because they didn’t

think it fit. So it fell between, and they never did it. It

was done later by Kenneth Gaburo and the New Music

Choral Ensemble, and it’s a nice piece. [See my Interview with Kenneth

Gaburo.] But anyway, I got to

thinking about the New Swingle Singers and he said, “I want you to

write the piece that you never wrote

for me.” So I did. I decided that it was going to be a

totally uncompromising statement of where I wanted to be technically,

so it’s ferociously hard.

BJ: I don’t get

that many so I usually

accept them. Well, actually, I don’t. Sometimes

people ask me to write pieces and I

just can’t find that I know what to write for them, so I end up not

doing it; or I try and I don’t like it, so I never give it to

them. But other times, somebody asks me to do

something, and I do find the right thing to do. So I go ahead

and do it, and I didn’t even expect to write that piece. I hadn’t

been thinking about it or anything else, but for

some reason something worked. It’s very hard to explain exactly

why that happens. I’m writing a cello piece for Laurien

Laufman. I hadn’t planned

to write a cello piece and I didn’t particularly want to, but I got

an idea that suited and I liked the way she played. So I just

wrote this piece very quickly and it worked fine. The other

one that I can think of is a piece I did for Richard Rood, a violinist

in a string quartet for New Music of

America when it was in Chicago. They played one of my

quartets and he liked it, so he said, “I have a group that is a

trio with a clarinet. I’m the violinist and there’s a

cellist. We have a

pianist, but you probably would want to use the trio,

because we don’t want to re-tune the piano.” So I said, “All

right, I’ll write

you a piece.” I had wanted to write a piece involving a

woodwind with strings, and that suited me very well. It’s a very

light piece and not very long, but it’s pleasant. So there’s one

that I just did without knowing

that I wanted to do it. Ward Swingle commissioned a

piece for the Swingle Singers. I had done them one at his request

earlier and he didn’t like it. What I did in that case was to do

a big band jazz piece for them with microtones. They said the

microtones made it

so hard that they couldn’t put it on their pops concerts, but they

didn’t want to put it on another kind of concert because they didn’t

think it fit. So it fell between, and they never did it. It

was done later by Kenneth Gaburo and the New Music

Choral Ensemble, and it’s a nice piece. [See my Interview with Kenneth

Gaburo.] But anyway, I got to

thinking about the New Swingle Singers and he said, “I want you to

write the piece that you never wrote

for me.” So I did. I decided that it was going to be a

totally uncompromising statement of where I wanted to be technically,

so it’s ferociously hard.

BD: Too hard?

BJ: No, it

isn’t too hard, but it’s at

the limit for one-on-a-part vocal. It wasn’t that I wanted to

make it so hard,

but I wanted to utilize all the overtones up through the sixteenth

partial. The

others aren’t prime, so they result from combinations. It was a

very

complex harmonic and melodic palette to be using. Also, I always

wanted to deal with Gerard Manley Hopkins, and that’s what those

sonnets are. They’re very powerful, being about spiritual

crisis and death, and they’re absolutely without parallel in the

English language. I think they’re amazing poems, so I was

really asking a lot of myself, but that was something that I just knew

I wanted to do. I wasn’t sure I could do it, but I wanted very

much to.

BD: When

you’re writing a piece, how do

you know when it’s finished?

BJ: If you’re

setting a

poem, that isn’t so much of a problem because in a certain sense, one

whole aspect of the work is already complete. You only try to

make

your contribution to it as appropriate as you can, and then you know

when you’re finished. Very often I will make a very

elaborate intellectual plan for the piece, and I will then structure

the piece around that. I plan the climaxes. I plan

everything including all the psychological events to work within that

structure, so when I come to the end of the structure, that’s it.

So I’m not usually through-composing and working blind. I often

compose that way if I’m dealing with a text, because then I

have something that is already composed, and I am dealing with it.

BD: Do you

ever find that when

you’re writing a piece, it goes in a direction you didn’t plan?

BJ: Oh yeah,

sure, sometimes to the extent

that you have to start all over. It’s as if the piece had a will

of its own,

and you only discover that after a while, and then have to undo all

those things that you were trying to impose on it which it wouldn’t

accept. I think it’s because anything we actually compose and

anything you do creatively is coming out of a

deeper stratum of yourself. I’m not trying to talk depth

psychology, it’s just that it’s not the ordinary level that is

speaking. The level that is speaking is not susceptible to your

everyday will. You can’t just turn it on and off like a

faucet. It comes and goes pretty much of its own

accord. That’s where all these symbols that have been used for

centuries come from — like the muse — because

they better describe the experience than something else does.

You’re not really being dictated to, but at the same time, something is

happening which you do not have volitional control over to a complete

extent, by any means. You can only modify it. It’s as if

you have a nozzle, and you can make a fine spray or a

coarse spray, but you can’t really change what’s coming out. It’s

water and that’s what’s

available, and what comes out is often is very

disconcerting. I think that’s

what’s wrong with Marxist theory when it comes to art. The idea

there is that you express true things about human life in art,

and you know beforehand what truths are so you use art to put

them across to other people. Well, art just doesn’t work that

way. It’s going to go its own way, and you don’t know what you’re

saying until you’ve said it!

BD: So, it’s

a constant discovery?

BJ: Yeah, and

so I think that that’s just

wrong-headed. That does not describe the way how art works, and

that is why Russians and all other Marxist countries always have a

problem with the arts. It’s because the Marxist theory just

doesn’t work that way in art. If you really believe and live

according to those

things, it would come out in your art anyway, and you wouldn’t even

have to try to make it do that. So the idea that you try to make

it do that is

wrong to begin with. That’s just an illustration of

what I’m saying, but there are a lot of other things that are like

that. If you are going to tailor-make what you’re doing for,

let’s say, a particular TV audience or a

commercial purpose, you’re up against a similar

problem. If you’re really making art, you don’t

know what’s really going to come out. You have to have enough

rope to hang yourself — which you might do [both

laugh] — but enough to make something

work! If

you’re on too tight a leash, nothing happens. It really has to be

loose. You have

to have a lot of lead to go and do things. It’s a lot like

science. You can’t just dictate to science; it’s what they’re

going to discover.

BD: Do you

ever go back and revise your scores?

BJ:

Yeah. I don’t too often go back to old

pieces and re-do them, but I have done that.

BD: What do

you say to future generations when the

musicologists are digging around and declare, “Here is the

urtext, so let us do that.”

BJ: I hope

they’ll have the good sense that

I’ve heard people express in terms of Hindemith’s revision of one of

his song cycles, the Marienleben.

The earlier version is much

better than the later version. And I hope people will be

able to say in other

cases that the later version is better than the earlier version, if it

is.

BD: So you

will let posterity decide which is the better

version?

BJ: Yeah,

sure in that case. I can’t think of a good example of that,

but some of Rimsky-Korsakov’s pieces that he re-did are genuinely

improved.

BD: What

always comes to mind for me is

Bruckner, but that’s because he was being screamed at by so many

people.

BJ:

[Laughs] I think if you’re that good,

even if you listen to all those people and get messed up, you don’t get

completely messed up.

BD: Is

composing fun?

BJ: Yes, of

course it is. It’s like any

other kind of creative activity — there’s a lot

of pain

involved and there are unpleasant reactions. I

suppose a lot of it is like having to deal with human

relationships that you wish you didn’t have to deal with, like being a

parent. There are certain things you would just as soon

not have to do, but you do have to do them. In a way they’re

the most rewarding things, but there’s an element of dread, almost, in

getting into them. Doing really important things with

your children often has that feeling about it.

BD: Do you

regard your scores as other children?

BJ: No, not

really, but there’s enough of

a parallel that there can be at least a little bit of comparison

made. The point is not that they’re like people, but one’s

feeling about them is a little bit like a parent has about a child, I

suppose. You have to let them go at a point. After they

have been played and they have their

life, you sort of don’t mess into them too much.

BD: Is the

audience always right in its opinions?

BJ: No, of

course not. In fact, audiences have

been resoundingly wrong at times, given the later

history of a work and what they thought it was and whether they

liked it or not. There’s nothing foolproof. It’s just that

in the long

run music is a communication of a sort, so if it doesn’t connect

ever, there’s something drastically wrong. So eventually, the

audience is not so much right as necessary.

BD: Thank you

for being a composer. [Picks up the text of Johnston’s

lecture for the upcoming symposium]

BJ: Well,

it’s a pleasure to do it. [Pointing to the printed text] I

had quite a struggle

writing that address because to say what I want to

say in it demands that I deal with what I am doing and how I think

about

it, and it gets to be I, I, I. I wanted very much to avoid that

kind

of ‘and then I wrote’ ex cathedra

attitude. It was not easy to do. Not that I

tend to want to speak that way, but I do believe in what I’m

doing, and when I get to talking about it, I can get very passionate

sometimes. It can sound to people as though I’m saying, “Why

don’t you quit doing all those things you’re doing and do

this?” which is really not what I meant! On the other hand, I

think what I’m doing is important,

or I wouldn’t do it.

BD: But you

allow for all kinds of other creativity?

BJ: To be

done also, yeah. What I hope I’ve

done is to put that into context, but that’s what made it hard to

write. Also, I tend to want to write very terse, densely packed

stuff, and that’s what I’ve done. So it’s going to be hard to

read out loud.

BD: I’m glad

we finally got together.

BJ: Yeah, I

am, too.

=====

===== =====

===== =====

-- -- -- -- -- -- -- --

===== =====

===== ===== =====

© 1987 Bruce Duffie

This interview was recorded in Chicago on April 7,

1987.

Portions (along with recordings)

were used on WNIB in 1991 and 1996, and on WNUR in 2006. This

transcription was

made and posted on this

website in 2012.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been

transcribed and posted on this website, click here. To

see the list of all of my guests and where their material has been

used, click here.

Award

- winning

broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago

from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of

2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and

journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM,

as well as on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio.

You are invited to visit his website

for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of

other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also

like

to call your attention to the photos and information about his

grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a

century ago. You may also send him E-Mail

with comments, questions and suggestions.

Ben Johnston

Ben Johnston BD

BD BJ

BJ BJ

BJ BJ

BJ BJ

BJ