|

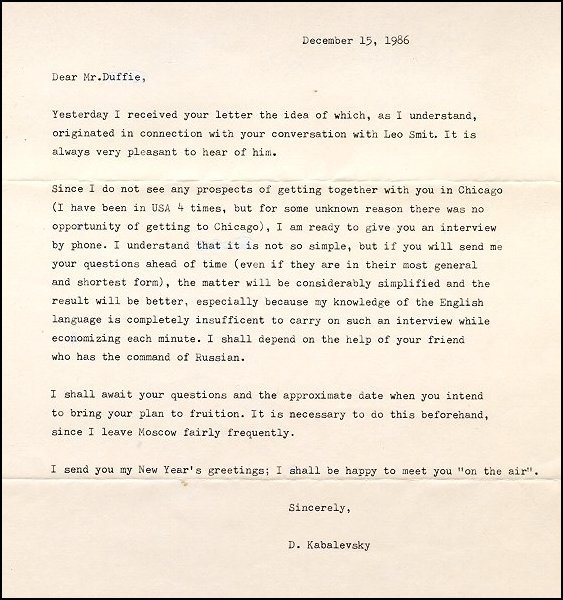

Alexander Siloti (1863 - 1945)

In the generation prior to 1917, Siloti was one of Russia's most important

artists, with music by Arensky, Liszt, Rachmaninoff, Stravinsky and Tchaikovsky

dedicated to him. At the Moscow Conservatory he studied piano with Zverev

from 1871, and under Nikolai Rubinstein, Taneyev, Tchaikovsky, and Hubert

from 1875. He graduated with the Gold Medal in Piano in 1881.

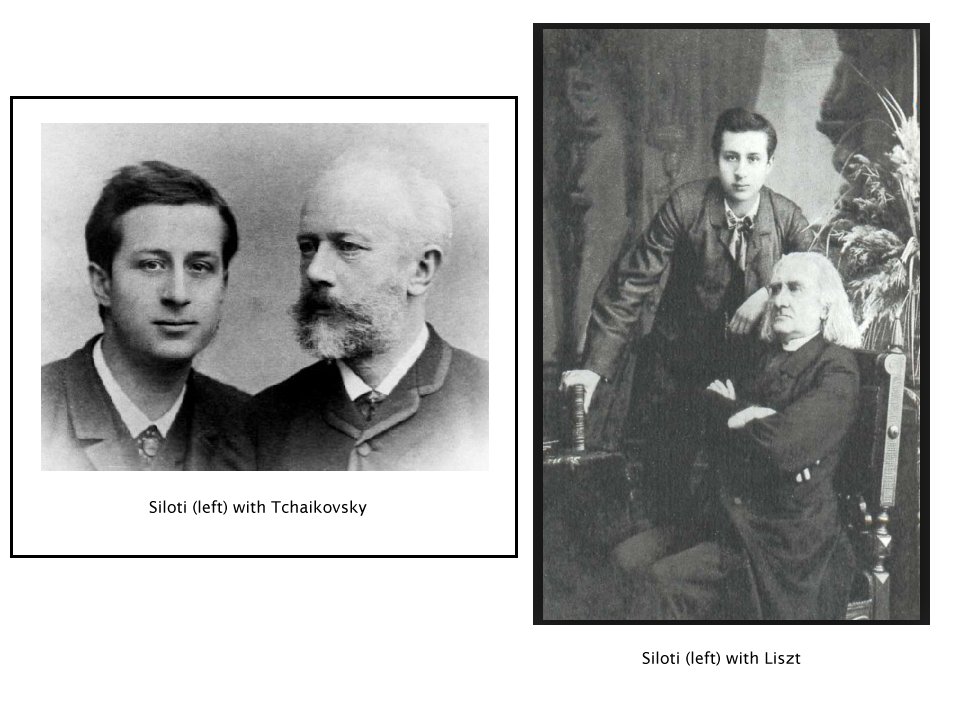

He worked with Liszt in Weimar (1883-1886), co-founded the Liszt-Verein

in Leipzig, and there made his professional debut on 19 November 1883. Returning

in 1887 Siloti taught at the Moscow Conservatory, where his students included

Goldenweiser, Maximov, and first-cousin Rachmaninov. In this period he began

work as editor for Tchaikovsky, particularly on the First and Second piano

concerti.

He quit the Conservatory in May 1891, and from 1892-1900 lived and toured

in Europe. He also toured New York, Boston, Cincinnati and Chicago in 1898.

From 1901-1903 Siloti led the Moscow Philharmonic; from 1903-1917 he organized,

financed, and conducted the supremely influential Siloti Concerts in St. Petersburg.

He presented Auer, Casals, Chaliapin, Enesco, Hofmann, Landowska, Mengelberg,

Mottl, Nikisch, Schoenberg and Weingartner, and local and world premieres

by Debussy, Elgar, Glazunov, Prokofiev, Rachmaninov, Rimsky-Korsakov, Scriabin,

Sibelius, Stravinsky and others. Diaghilev first heard Stravinsky at a Siloti

Concert.

In 1918 Siloti was appointed Intendant of the Mariinsky Theatre, but late

the following year fled Soviet Russia for England, finally settling in New

York in December 1921. From 1925-1942 he taught at the Juilliard Graduate

School, performing occasionally in recital, and in November 1930 gave a legendary

all-Liszt concert with Toscanini. Siloti's private students included Marc

Blitzstein and Eugene Istomin.

He wrote over 200 piano arrangements and transcriptions, and orchestral

editions of Bach, Beethoven, Liszt, Tchaikovsky and Vivaldi. Even though

he had a great repertoire and was a famous figure during his life, his fame

has gradually faded away making him quite unknown to most people of today

.

|

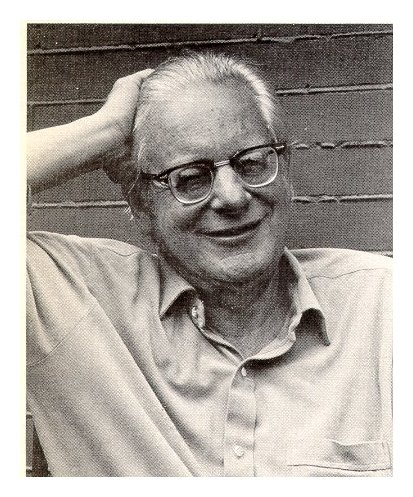

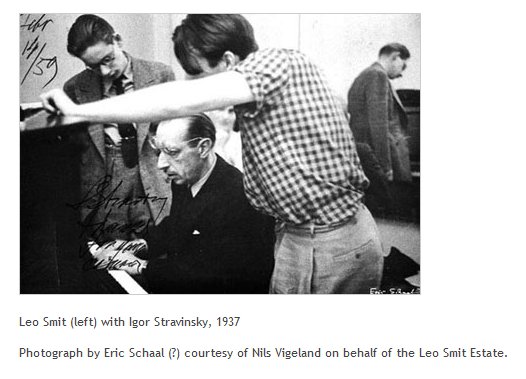

LS

LS BD

BD LS

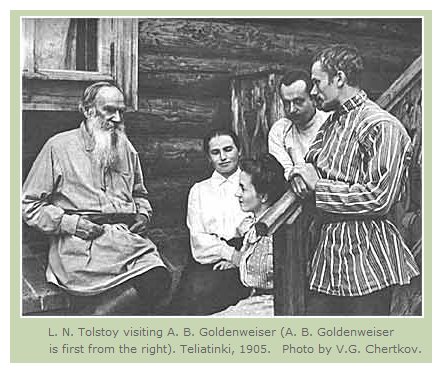

LS Pianist and composer Alexander Goldenweiser was one of the great founders

of the Russian Piano School, a tirelessly dedicated pedagogue who helped establish

the very system of teaching piano in Russia that has led to many successful

concert artists. Born in what is now Chisinau, Moldova, Goldenweiser's musical

training as pianist and composer commenced once his family settled in Moscow

in 1883, taking private lessons with Vasily Prokhunin, a student of Tchaikovsky.

Goldenweiser's term as student at the Moscow Conservatory began in 1889,

where he studied with Alexander Siloti, Sergey Taneyev, Ferruccio Busoni,

and Anton Arensky; he made his debut in 1896 in a duet recital with fellow

student Sergey Rachmaninoff. In his youth, Goldenweiser was a close friend

of author Leo Tolstoy, and transcribed practically every word they shared

together, publishing such comments in book form after Tolstoy died in 1910.

We also owe the existence of Tolstoy's only musical composition to Goldenweiser,

who took it down after Tolstoy played it to him in 1906.

Pianist and composer Alexander Goldenweiser was one of the great founders

of the Russian Piano School, a tirelessly dedicated pedagogue who helped establish

the very system of teaching piano in Russia that has led to many successful

concert artists. Born in what is now Chisinau, Moldova, Goldenweiser's musical

training as pianist and composer commenced once his family settled in Moscow

in 1883, taking private lessons with Vasily Prokhunin, a student of Tchaikovsky.

Goldenweiser's term as student at the Moscow Conservatory began in 1889,

where he studied with Alexander Siloti, Sergey Taneyev, Ferruccio Busoni,

and Anton Arensky; he made his debut in 1896 in a duet recital with fellow

student Sergey Rachmaninoff. In his youth, Goldenweiser was a close friend

of author Leo Tolstoy, and transcribed practically every word they shared

together, publishing such comments in book form after Tolstoy died in 1910.

We also owe the existence of Tolstoy's only musical composition to Goldenweiser,

who took it down after Tolstoy played it to him in 1906.

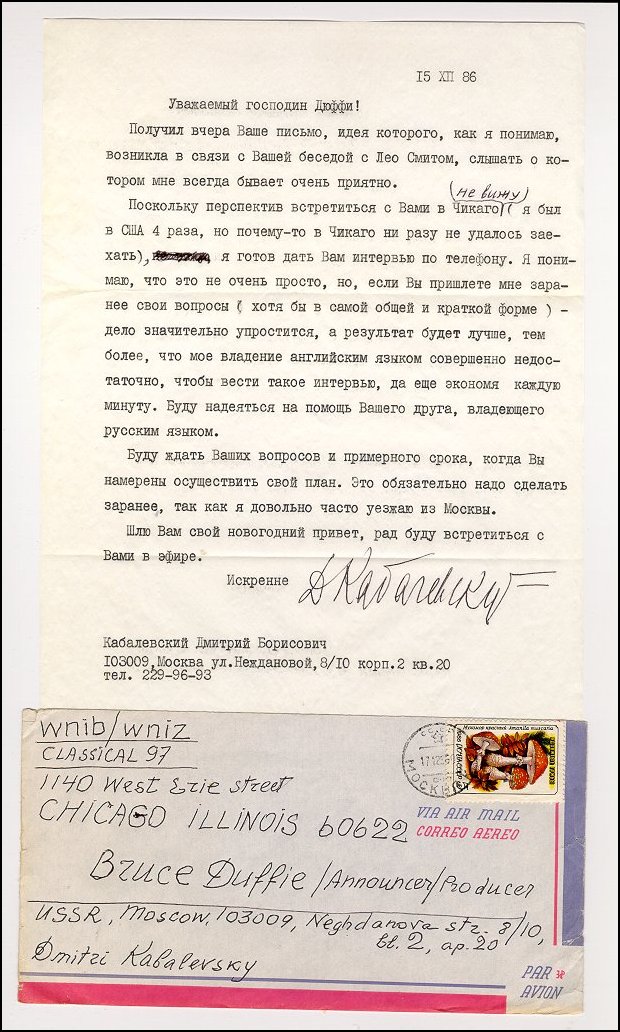

BD

BD

LS

LS BD

BD BD

BD