|

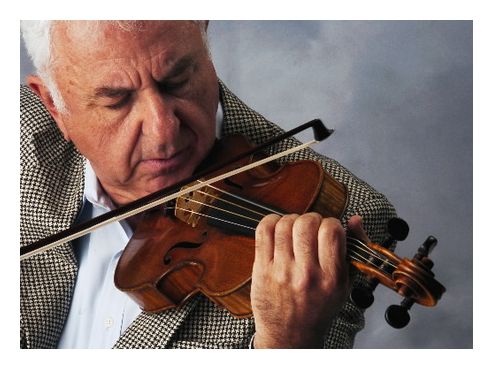

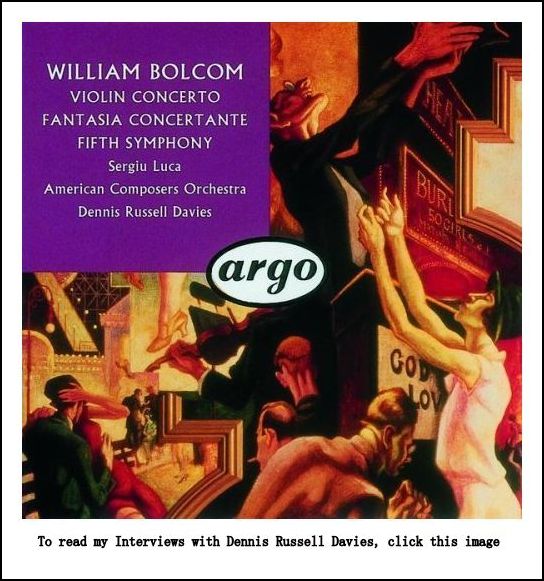

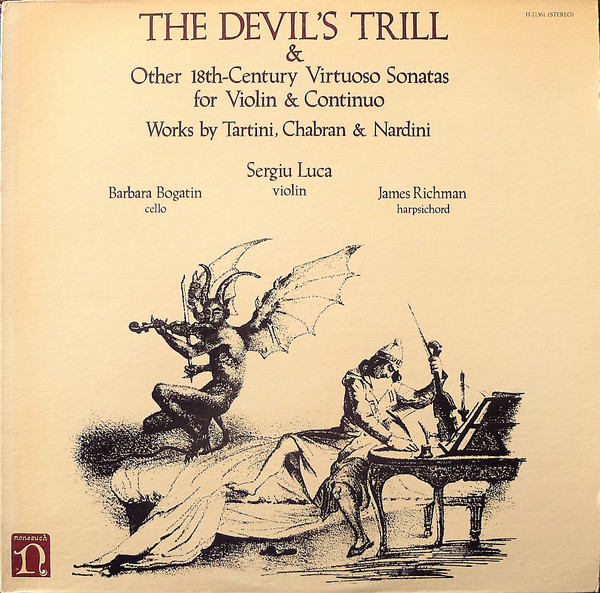

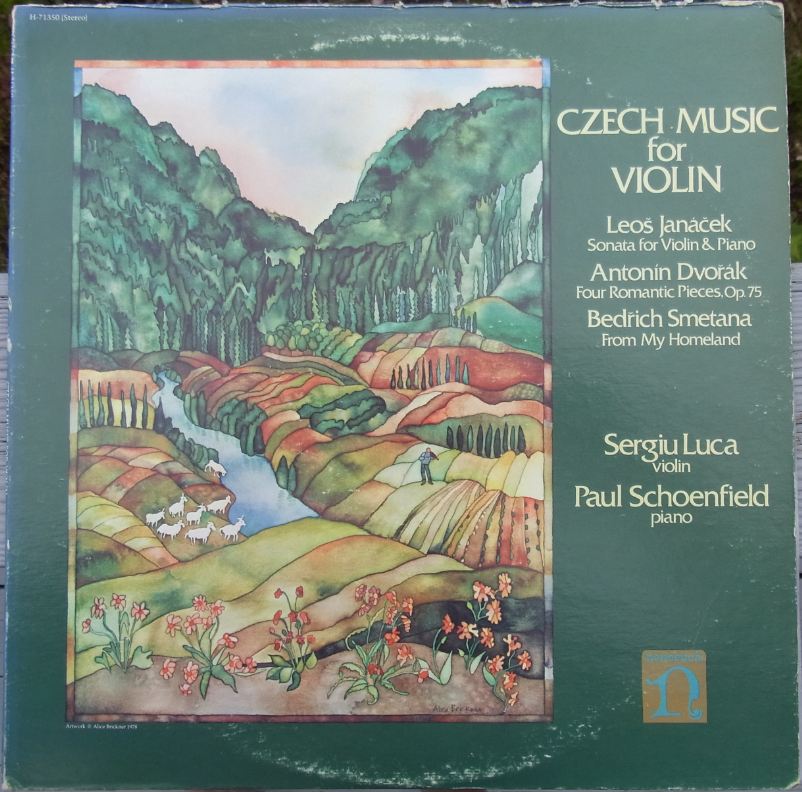

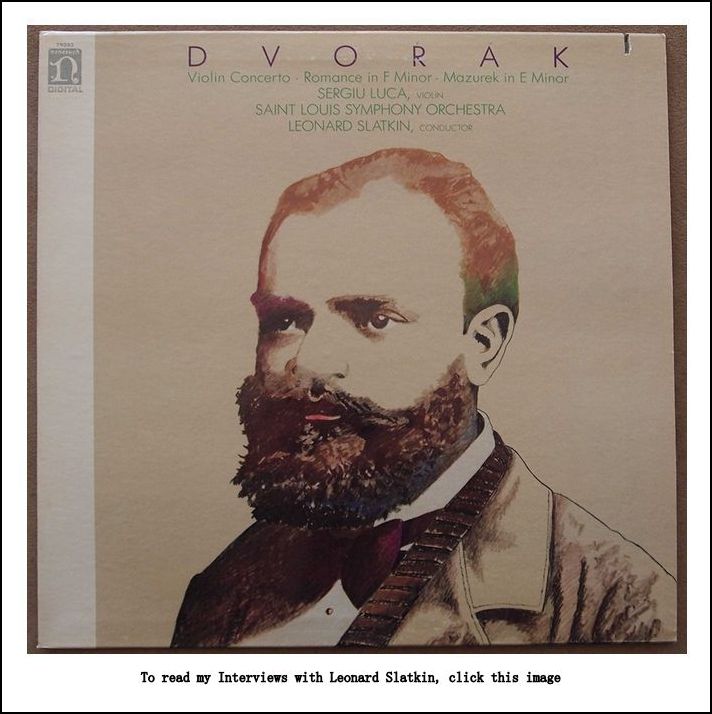

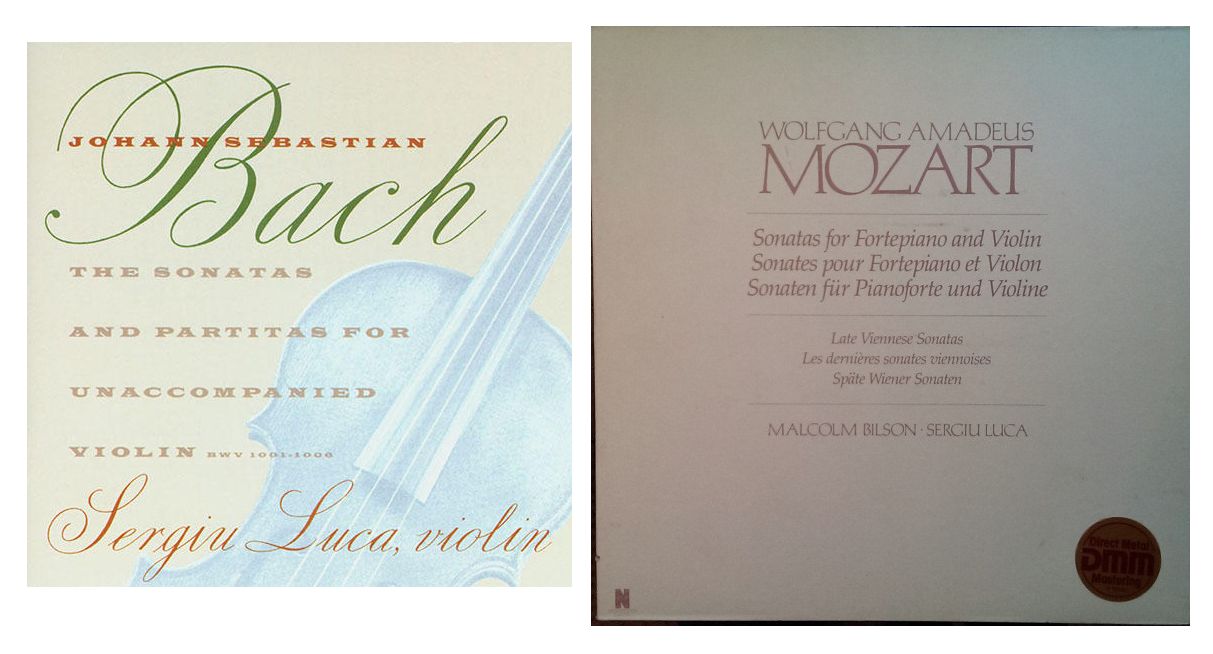

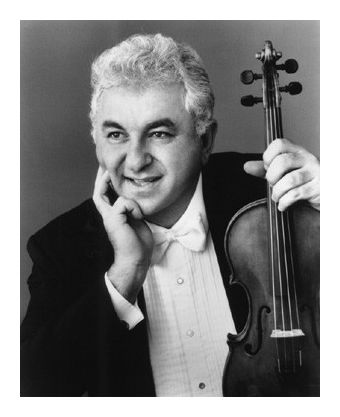

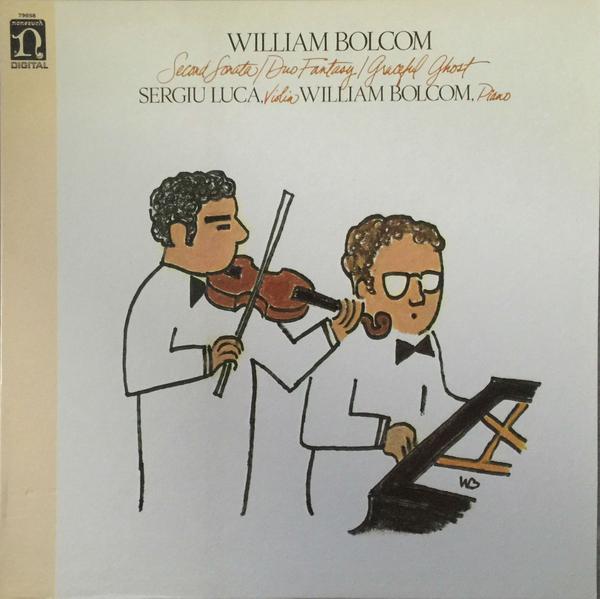

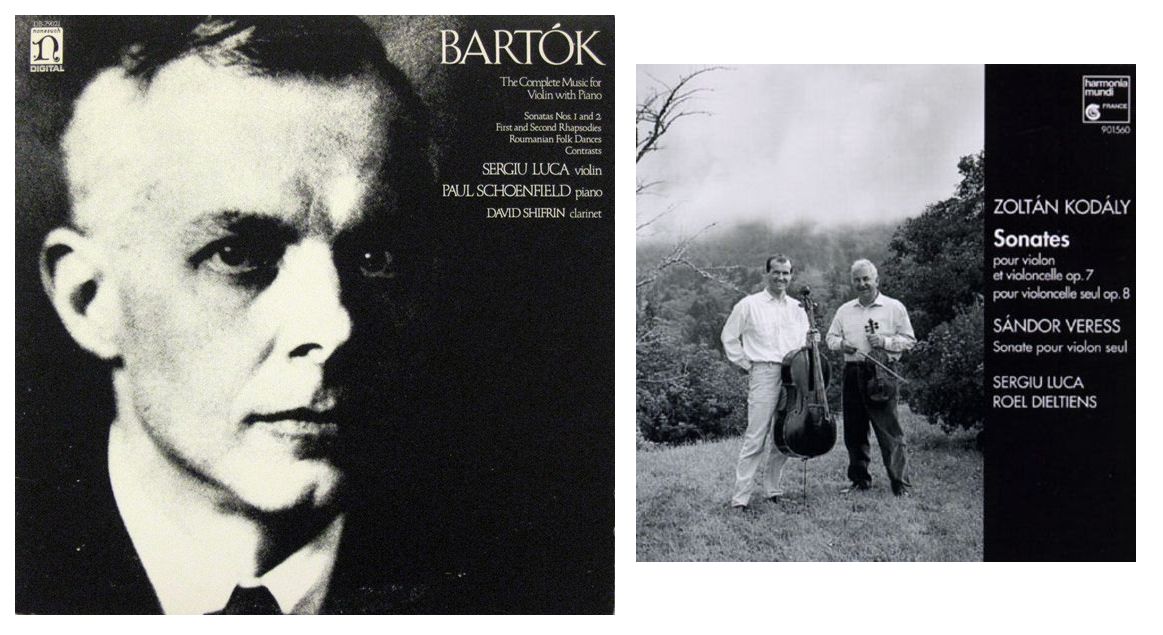

Sergiu Luca (5 April 1943, in Bucharest – 6 December 2010, in Houston) was a Romanian-born American violinist, renowned as an early music pioneer. During his career he performed and recorded on both baroque and modern violins. Luca was born in Bucharest, Romania, but his family moved to Israel at his age of 7, and as a 9 year old he debuted with the Haifa Symphony Orchestra. Before going to the United States to study at the Curtis Institute with Ivan Galamian he studied in London and Switzerland. His American debut was Sibelius's Violin Concerto with the Philadelphia Orchestra in 1965, on which occasion he was chosen by Leonard Bernstein to play its first movement with him conducting the New York Philharmonic later that year. During his career he recorded J. S. Bach's entire oeuvre for solo violin, the Brandenburg Concertos (with Pablo Casals), and a portion of the romantic and 20th century repertoire. In 1971 he launched the Chamber Music Northwest festival in Portland, Oregon; in 1983 he took the direction of Houston's Texas Chamber Orchestra which he held until 1986 when he founded the Cascade Head Music Festival on the Oregon Coast; in 1988 he founded Da Camera Society of Houston. He was one of the founders of the Context chamber group. From 1983 until his death he was a professor at William Marsh Rice University. |

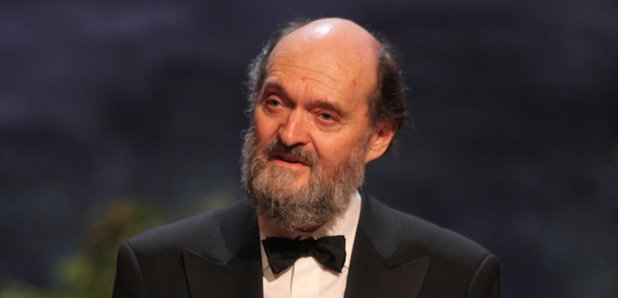

Arvo Pärt (born 11 September 1935) is an Estonian composer of classical and religious music. Since the late 1970s, Pärt has worked in a minimalist style that employs his self-invented compositional technique, tintinnabuli. This simple style was influenced by the composer's mystical experiences with chant music. Musically, Pärt's tintinnabular music is characterized by two types of voice, the first of which (dubbed the "tintinnabular voice") arpeggiates the tonic triad, and the second of which moves diatonically in stepwise motion. The works often have a slow and meditative tempo, and a minimalist approach to both notation and performance. Pärt's compositional approach has expanded somewhat in the years since 1970, but the overall effect remains largely the same. |

SL: Society? I’m not society! I can tell

you what the purpose of music is for me. [Has a huge laugh]

SL: Society? I’m not society! I can tell

you what the purpose of music is for me. [Has a huge laugh] BD: But it is based in Houston and

will give concerts throughout the year?

BD: But it is based in Houston and

will give concerts throughout the year? BD: It gets boring for you, and that in turn makes

it boring for the audience?

BD: It gets boring for you, and that in turn makes

it boring for the audience?

SL: I’d like to assume so. The Da Camera Society

is a sign of evolution. I’ve decided to take some of my time and

energy, and some of the talents I have, and put them into social music,

or organization music, for a career that makes music possible

— not just whenever I play, but when others play. Music’s

being played all the time, and who knows what the evolution is?

I have an electric violin on which I play some jazz, and my mind is constantly

torn back and forth between the fact that I have a beautiful Strad

— and it sounds fabulous — and yet it’s

been tweaked up in order to fill the halls I play most of the time. Ninety

per cent of my playing needs force, and therefore my nuance possibilities

remain at ten per cent. Then when I put an amplifier on a cheap violin,

my nuance possibilities and range become enormous. I don’t know what

it means. All I know is that being a violinist of the lineage with

all that attached to me would not probably fit this person.

SL: I’d like to assume so. The Da Camera Society

is a sign of evolution. I’ve decided to take some of my time and

energy, and some of the talents I have, and put them into social music,

or organization music, for a career that makes music possible

— not just whenever I play, but when others play. Music’s

being played all the time, and who knows what the evolution is?

I have an electric violin on which I play some jazz, and my mind is constantly

torn back and forth between the fact that I have a beautiful Strad

— and it sounds fabulous — and yet it’s

been tweaked up in order to fill the halls I play most of the time. Ninety

per cent of my playing needs force, and therefore my nuance possibilities

remain at ten per cent. Then when I put an amplifier on a cheap violin,

my nuance possibilities and range become enormous. I don’t know what

it means. All I know is that being a violinist of the lineage with

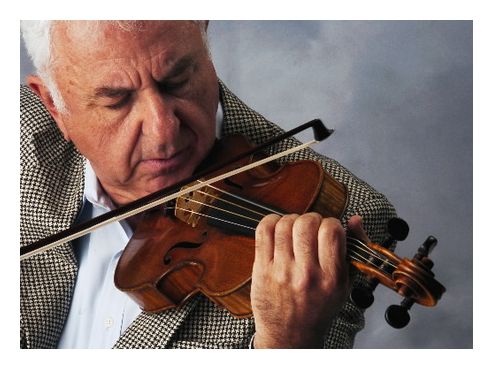

all that attached to me would not probably fit this person.  BD: But you have made a number of recordings...

BD: But you have made a number of recordings...|

He was born in Tabriz, Persia on February 5, 1903. His parents were Armenians from Russia, but his family emigrated to Moscow soon after his birth. Galamian studied violin at the School of the Philharmonic Society there with Konstantin Mostras (a student of Leopold Auer) until his graduation in 1919. He moved to Paris during the Bolshevik Revolution and studied under Lucien Capet in 1922 and 1923. In 1924 he debuted in Paris. Due to a combination of nerves, health, and a fondness for teaching, Galamian eventually gave up the stage in order to teach full-time. He became a faculty member of the Russian Conservatory in Paris, where he taught from 1925 until 1929. His earliest pupils in Paris include Vida Reynolds, the first woman in the Philadelphia Orchestra's first violin section. In 1937 Galamian moved permanently to the United States. In 1941 he married Judith Johnson in New York City. He taught violin at the Curtis Institute of Music beginning in 1944, and became the head of the violin department at the Juilliard School in 1946. He wrote two violin method books, Principles of Violin Playing and Teaching (1962) and Contemporary Violin Technique (1962). Galamian incorporated aspects of both the Russian and French schools of violin technique in his approach. Galamian founded the summer program Meadowmount School of Music in Westport, NY. Some of his most well known pupils are Itzhak Perlman, Pinchas Zukerman, Kyung-Wha Chung, and Michael Rabin. His most notable teaching assistants — later distinguished teachers in their own right — include Dorothy Delay. Galamian passed away on April 14, 1981. |

|

Johann Nepomuk Hummel (14 November 1778 – 17 October 1837)

was an Austrian composer and virtuoso pianist. His music reflects the transition

from the Classical to the Romantic musical era.

Hummel's father then took him on a European tour, arriving in London where he received instruction from Muzio Clementi, and where he stayed for four years before returning to Vienna. In 1791 Joseph Haydn, who was in London at the same time as young Hummel, composed a sonata in A-flat major for Hummel, who gave its first performance in the Hanover Square Rooms in Haydn's presence. When Hummel finished, Haydn reportedly thanked the young man and gave him a guinea. The outbreak of the French Revolution and the following Reign of Terror caused Hummel to cancel a planned tour through Spain and France. Instead, he returned to Vienna, giving concerts along his route. Upon his return to Vienna he was taught by Johann Georg Albrechtsberger, Joseph Haydn, and Antonio Salieri. At about this time, young Ludwig van Beethoven arrived in Vienna and also took lessons from Haydn and Albrechtsberger, thus becoming a fellow student and a friend. Beethoven's arrival was said to have nearly destroyed Hummel's self-confidence, though he recovered without much harm. The two men's friendship was marked by ups and downs, but developed into reconciliation and mutual respect. Hummel visited Beethoven in Vienna on several occasions with his wife Elisabeth and pupil Ferdinand Hiller. At Beethoven's wish, Hummel improvised at the great man's memorial concert. It was at this event that he made friends with Franz Schubert, who dedicated his last three piano sonatas to Hummel. However, since both composers had died by the time of the sonatas' first publication, the publishers changed the dedication to Robert Schumann, who was still active at the time. In 1804, Hummel became Konzertmeister to Prince Esterházy's establishment at Eisenstadt. Although he had taken over many of the duties of Kapellmeister because Haydn's health did not permit him to perform them himself, he continued to be known simply as the Concertmeister out of respect to Haydn, receiving the title of Kapellmeister, or music director, to the Eisenstadt court only after the older composer died in May 1809. He remained in the service of Prince Esterházy for seven years altogether before being dismissed in May 1811 for neglecting his duties. He then returned to Vienna where, after spending two years composing, he married the opera singer Elisabeth Röckel in 1813. The following year, at her request, was spent touring Russia and the rest of Europe. The couple had two sons. One of them, Carl (1821–1907), became a well-known landscape painter. Hummel later held the positions of Kapellmeister in Stuttgart from

1816 to 1819 and in Weimar from 1819 to 1837, where he formed a close

friendship with Goethe, learning among other things to appreciate the

poetry of Schiller, who had died in 1805. During Hummel's stay in Weimar

he made the city into a European musical capital, inviting the best musicians

of the day to visit and make music there. He brought one of the first musicians'

pension schemes into existence, giving benefit concert tours when the

retirement fund ran low. Hummel was one of the first to agitate for musical

copyright to combat intellectual piracy.

Dussek was one of the first piano virtuosos to travel widely throughout Europe. He performed at courts and concert venues from London to Saint Petersburg to Milan, and was celebrated for his technical prowess. During a nearly ten-year stay in London, he was instrumental in extending the size of the pianoforte, and was the recipient of one of John Broadwood's first 6-octave pianos, CC-c4. Harold Schonberg wrote that he was the first pianist to sit at the piano with his profile to the audience, earning him the appellation "le beau visage." All subsequent pianists have sat on stage in this manner. He was one of the best-regarded pianists in Europe before Beethoven's rise to prominence. His music is marked by lyricism interrupted by sudden dynamic contrasts.

Not only did he write prolifically for the piano, he was an important

composer for the harp. His music for that instrument contains a great

variety of figuration within a largely diatonic harmony, avoids dangerous

chromatic passages and is eminently playable. His music is considered standard

repertoire for all harpists, particularly his Six Sonatas/Sonatinas and

especially the Sonata in C minor. Less well known to the general public

than that of his more renowned Classical period contemporaries, his piano

music is highly valued by many teachers and not infrequently programmed.

Franz Liszt has been called an indirect successor of Dussek in the composition

and performance of virtuoso piano music. His music remained popular to some degree in 19th-century Great Britain and the USA, and some of it is still in print, with much more becoming available in period editions found online. |

BD: Where are you from originally?

BD: Where are you from originally?

|

Giuseppe "Joe" Venuti (possibly September 16, 1903 – August 14, 1978)

was an Italian-American jazz musician and pioneer jazz violinist. Venuti was well known for giving out conflicting information regarding his early life, including his birthplace and birth date as well as his education and upbringing. Gary Giddins summarized the situation by saying that, "Depending on which reference book you consult, (Venuti's age when he died in 1978) was eighty-four, eighty-two, eighty, seventy-five, seventy-four, or seventy-two. Venuti, who surely had one of the strangest senses of humor in music history, encouraged the confusion." Venuti claimed to have been born aboard a ship as his parents emigrated from Italy around 1904, though many believe he was born in Philadelphia. It has also been claimed that he was born on April 4, 1898 in Lecco, Italy, or on September 16, 1903 in Philadelphia. Later in life, he said he was born in Lecco, Italy in 1896 and that he came to the U.S. in 1906 and settled in Philadelphia.

Considered the father of jazz violin, he pioneered the use of string instruments in jazz along with the guitarist Eddie Lang, a friend since childhood. Through the 1920s and early 1930s, Venuti and Lang made many recordings, as leader and as featured soloists. He and Lang became so well known for their 'hot' violin and guitar solos that on many commercial dance recordings they were hired to do 12- or 24-bar duos towards the end of otherwise stock dance arrangements. In 1926, Venuti and Lang started recording for the OKeh label as a duet (after a solitary duet issued on Columbia), followed by "Blue Four" combinations, which are considered milestone jazz recordings. Venuti also recorded commercial dance records for OKeh under the name "New Yorkers". He worked with Benny Goodman, Adrian Rollini, the Dorsey Brothers, Bing Crosby, Bix Beiderbecke, Jack Teagarden, Frank Signorelli, the Boswell Sisters, and most of the other important white jazz and semi-jazz figures of the late 1920s and early 1930s. However, following Lang's death in 1933, Venuti's career began to wane, though he continued performing through the 1930s, recording a series of commercial dance records (usually containing a Venuti violin solo) for the dime store labels, OKeh and Columbia, as well as the occasional jazz small group sessions. He was also a strong early influence on western swing players like Cecil Brower. Many of the 1920s OKeh sides continued to sell through 1935, when ARC reissued selected sides on the 35-cent Vocalion label. After a period of relative obscurity in the 1940s and 1950s, Venuti

played violin and other instruments with Jack Statham at the Desert Inn

Hotel in Las Vegas. Statham headed several musical groups that played

at the Desert Inn from late 1961 until 1965, including a Dixieland combo.

Venuti was with him during that time, and was active with the Las Vegas

Symphony Orchestra during the 1960s. He was 'rediscovered' in the late

1960s. In the 1970s, he established a musical relationship with tenor saxophonist

Zoot Sims that resulted in three recordings. In 1976, he recorded an album

of duets with pianist Earl Hines entitled "Hot Sonatas." He also recorded

an entire album with country-jazz musicians including mandolinist Jethro

Burns (of Homer & Jethro), pedal steel guitarist Curly Chalker and

former Bob Wills sideman and guitarist Eldon Shamblin. Venuti died in Seattle,

Washington. Venuti pioneered the violin as a solo instrument to the jazz world. He was famous for a fast, "hot" playing style characteristic of jazz soloists in the 1920s and the swing era. His solos have been described as incredibly rhythmic with patterns of duplets and running eighth and sixteenth notes. He favored a lively, fast tempo that showed off his superior technique. Venuti was a virtuosic player with a wide range of techniques, including left-hand pizzicato and runs spanning the length of the fingerboard. He also frequently implemented slides common in blues and country fiddle playing. Occasionally, he used an uncommon technique in which he unscrewed the end of his bow and wrapped the bow hair around the strings of the violin, allowing him to play chords, lending the subsequent sound a "wild" tone. He was particularly notable in small ensemble jazz, since — prior to the invention of the musical amplifier — the force of the horns in big band jazz was sufficient to drown out the violin. |

© 1988 Bruce Duffie

This conversation was recorded in Chicago on June 28, 1988. Portions were broadcast on WNIB later that evening, and again in 1993 and 1998. This transcription was made in 2017, and posted on this website at that time. My thanks to British soprano Una Barry for her help in preparing this website presentation.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website, click here.

Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM, as well as on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio.

You are invited to visit his website for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.