|

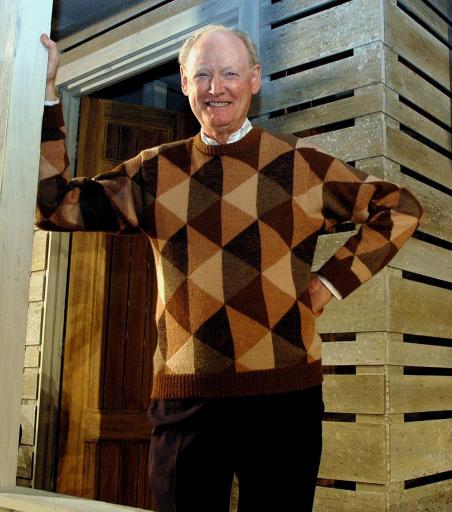

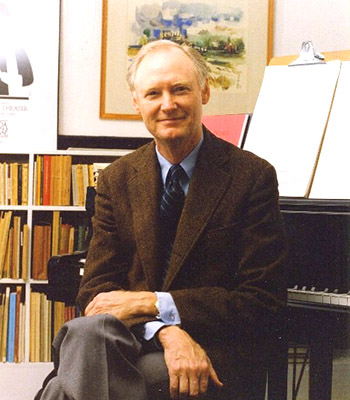

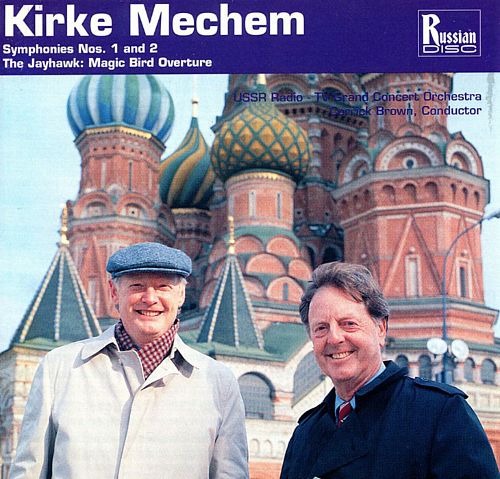

Kirke Mechem (August 16, 1925 - ) is a prolific composer with a catalogue of over 250 works. He enjoys an international presence, as ASCAP recently registered concert performances of his music in 42 countries. Born and raised in Kansas and educated at Stanford and Harvard Universities, Mechem conducted and taught at Stanford, and served as composer-in-residence for several years at the University of San Francisco. Mechem also lived in Europe, spending three years in Vienna where he came to the attention of Josef Krips, who later championed the composer's symphonies as conductor of the San Francisco Symphony. He was guest of honor at the 1990 Tchaikovsky Competition in Moscow and was invited back for an all-Mechem symphonic concert by the USSR Radio-Television Orchestra in 1991. He has been honored and recognized for his contributions from the United Nations; the National Endowment for the Arts; the National Gallery; the American Choral Directors Association; the Music Educators National Conference, and was presented with a lifetime achievement award from the National Opera Association. In 2012 the University of Kansas awarded him the honorary degree of Doctor of Arts. Mechem's compositions cover almost every

genre, but vocal music is the core of his work. His three-act opera,

Tartuffe, has been performed nearly 400 times in six countries.

His extensive choral works have garnered him the title of "Dean of American

Choral Composers." The premiere of Mechem’s large-scale dramatic opera based

on American abolitionist John Brown was commissioned to celebrate Lyric

Opera Kansas City's 50th anniversary. Songs of the Slave — a suite

for bass-baritone, soprano, chorus and orchestra from John Brown

— has been performed over 90 times. His comic opera, The Rivals (an

American update of Sheridan’s classic play of the same name), was premiered

in 2011 by Skylight Opera in Milwaukee. Mechem has recently completed an

opera based on Jane Austen's Pride and Prejudice.

His memoir, Believe Your Ears: Life

of a Lyric Composer, was published by Rowman & Littlefield in 2015.

It won ASCAP Foundation's 48th annual Deems Taylor/Virgil Thomson Award for outstanding

musical biography. — (mostly) G. Schirmer, 2015

-- Note that links in this box, and below,

refer to my Interviews elsewhere on my website. BD

|

Kirke Mechem: Oh there are lots of joys, and the

sorrows are only when the voice is not human. [Laughs] One

of the things I wish that I had was a beautiful voice. I love to

sing, but I never really had a good voice. I’ve sung a lot in choruses,

and that’s what really turned me on to writing for the voice. In

college I’d been playing music by ear and writing wretched songs, and I

finally began to study harmony just for the fun of it. Although I

was an English major at Stanford, singing in the chorus is the thing that

really turned me on. To suddenly hear the third of the chord coming

from over here, and fifth coming from over there, and they’re all singing

beautiful lines, it was suddenly like technicolor instead of the black and

white keyboard. I hadn’t yet learned to write music away from the piano.

I really got hooked on choral music then, and so my first serious music

was choral music, and even though I moved on to chamber music and symphonies

and opera and piano music, I always come back to choral music. It’s

a beautiful medium.

Kirke Mechem: Oh there are lots of joys, and the

sorrows are only when the voice is not human. [Laughs] One

of the things I wish that I had was a beautiful voice. I love to

sing, but I never really had a good voice. I’ve sung a lot in choruses,

and that’s what really turned me on to writing for the voice. In

college I’d been playing music by ear and writing wretched songs, and I

finally began to study harmony just for the fun of it. Although I

was an English major at Stanford, singing in the chorus is the thing that

really turned me on. To suddenly hear the third of the chord coming

from over here, and fifth coming from over there, and they’re all singing

beautiful lines, it was suddenly like technicolor instead of the black and

white keyboard. I hadn’t yet learned to write music away from the piano.

I really got hooked on choral music then, and so my first serious music

was choral music, and even though I moved on to chamber music and symphonies

and opera and piano music, I always come back to choral music. It’s

a beautiful medium.  BD: But you had to make sure it hangs together.

BD: But you had to make sure it hangs together. KM: Absolutely. That’s why I gave up trying to tell

performers exactly how to do everything, because I find that when you do

that, you shut off their creativity and their innate musicality, and they

don’t give nearly as much to the performance if they think they’re just

doing this to please you. I trust their musicality. I always

tell performers that I’m careful about the way I notate my tempos and everything,

but every situation’s different, every voice is different, every hall is

different, and you feel different at different times. So try it my

way scrupulously, and then make it your own. If it doesn’t work my

way, work until you see what I want and try to find how you can do that.

In doing so, I get a lot of pleasant surprises. I didn’t learn this

until my music started getting published and I started hearing people perform

my music whom I didn’t know. They would perform it in a way that I

hadn’t quite thought of. They would take a section a little slower,

and I would see that it works better that way.

KM: Absolutely. That’s why I gave up trying to tell

performers exactly how to do everything, because I find that when you do

that, you shut off their creativity and their innate musicality, and they

don’t give nearly as much to the performance if they think they’re just

doing this to please you. I trust their musicality. I always

tell performers that I’m careful about the way I notate my tempos and everything,

but every situation’s different, every voice is different, every hall is

different, and you feel different at different times. So try it my

way scrupulously, and then make it your own. If it doesn’t work my

way, work until you see what I want and try to find how you can do that.

In doing so, I get a lot of pleasant surprises. I didn’t learn this

until my music started getting published and I started hearing people perform

my music whom I didn’t know. They would perform it in a way that I

hadn’t quite thought of. They would take a section a little slower,

and I would see that it works better that way.  KM: No more! I haven’t for about twelve or fifteen

years. I’ve been able to do without it, and it’s a great luxury

KM: No more! I haven’t for about twelve or fifteen

years. I’ve been able to do without it, and it’s a great luxury

KM: Anyone can do anything he or she likes. That’s

fine, and anyone is perfectly able to write it and to listen to it.

[Hesitates a moment] But to be objective, to look at what’s happened

to the music, one can certainly see that it has not been very communicative

to many people. Never before in history has so much been written for

so few.

KM: Anyone can do anything he or she likes. That’s

fine, and anyone is perfectly able to write it and to listen to it.

[Hesitates a moment] But to be objective, to look at what’s happened

to the music, one can certainly see that it has not been very communicative

to many people. Never before in history has so much been written for

so few. BD: You do get some advance commissions, though?

BD: You do get some advance commissions, though?

© 1991 Bruce Duffie

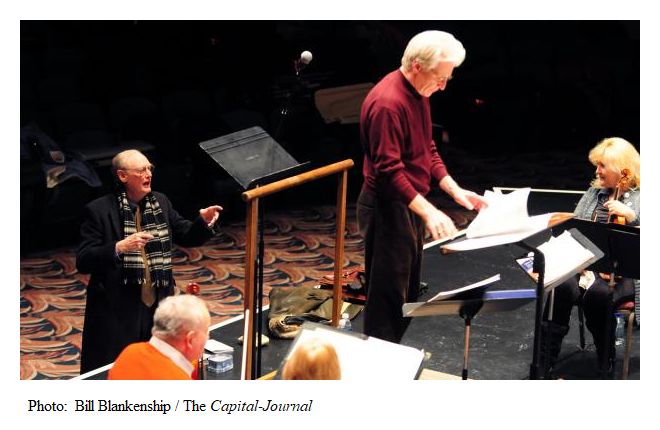

This conversation was recorded in Chicago on November 16, 1991. Portions were broadcast on WNIB in 1993, 1995, and 2000. This transcription was made in 2017, and posted on this website at that time. My thanks to British soprano Una Barry for her help in preparing this website presentation.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website, click here.

Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM.

You are invited to visit his website for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.