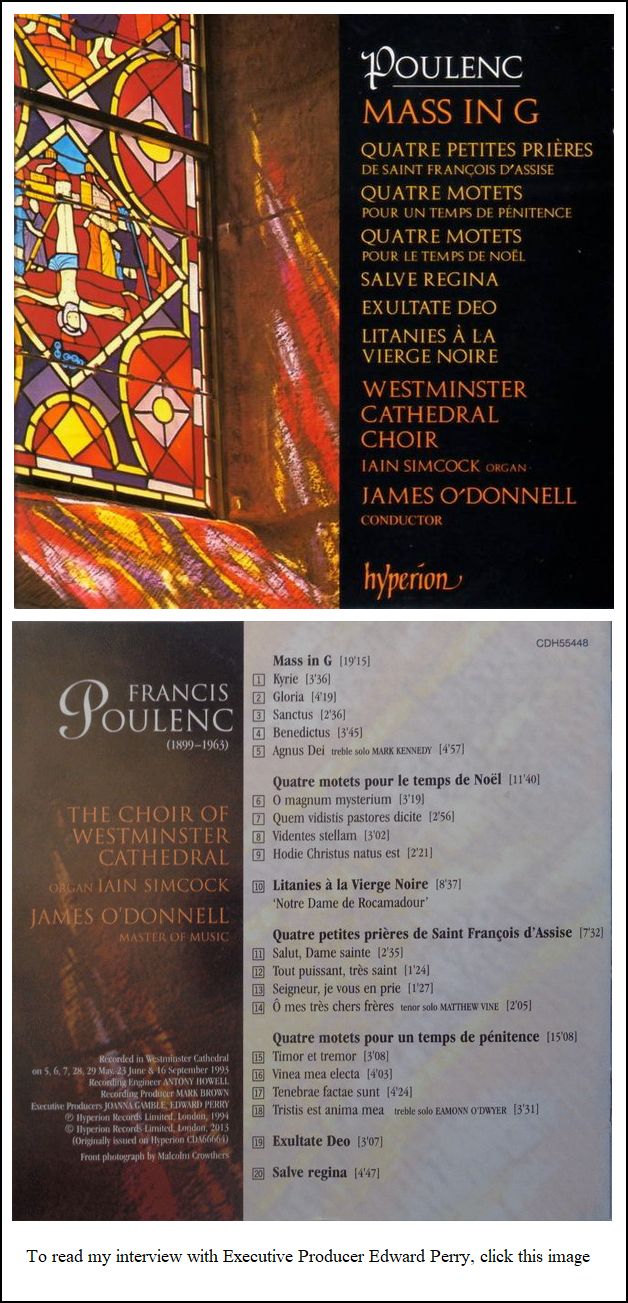

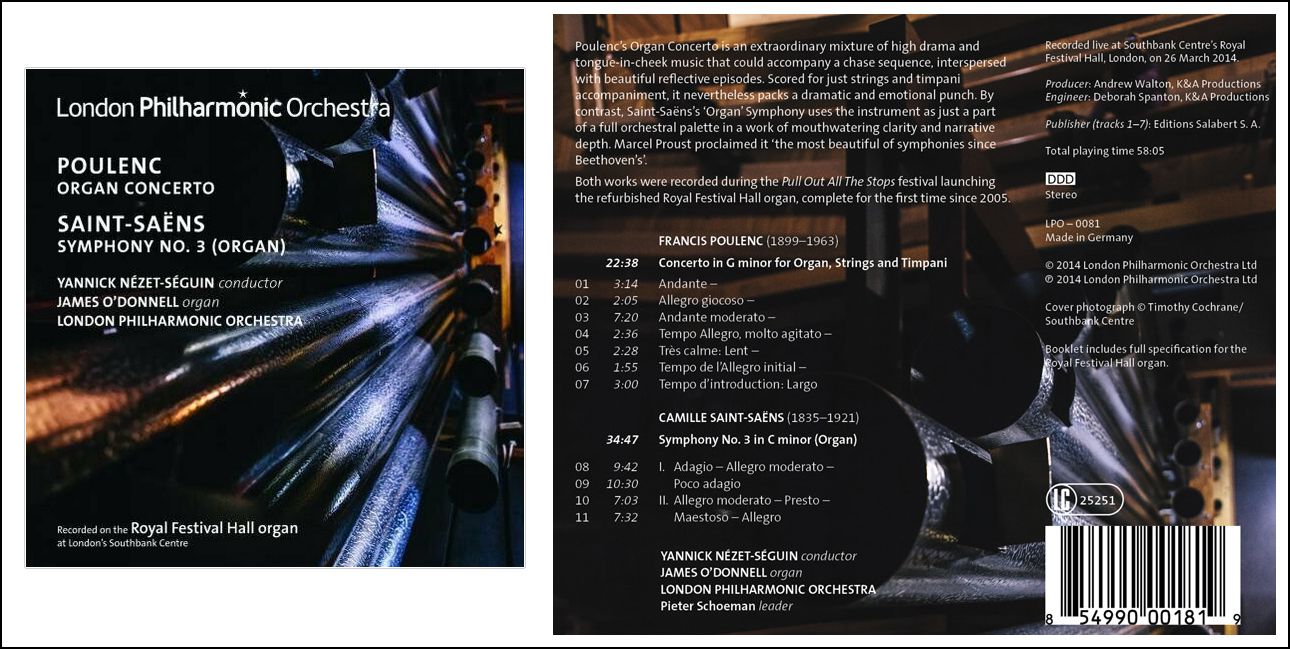

James O'Donnell is among the leading British organists of his generation. While some might further define him as a church organist and choir director -- roles he has fulfilled with the utmost commitment -- he has been active on the concert stage both as an organist and conductor. His choice of repertory has been broad, taking in the music of Renaissance-era icons like Palestrina and Josquin Desprez, as well as that of 20th century masters like Stravinsky and Poulenc. O'Donnell has made more than 40 recordings for the Hyperion label.

O'Donnell was born in Scotland on August 15, 1961. While in his

teens, he won a scholarship to the Royal College of Music. Later he was

chosen organ scholar at Cambridge University (Jesus College), where he would

go on to win several prizes and honors for organ performance. His teachers

there were Nicholas Kynaston, Peter Hurford, and David

Sanger. Shortly after his 1982 graduation, O'Donnell began his long relationship

with Westminster Cathedral, serving there initially as Assistant Master of

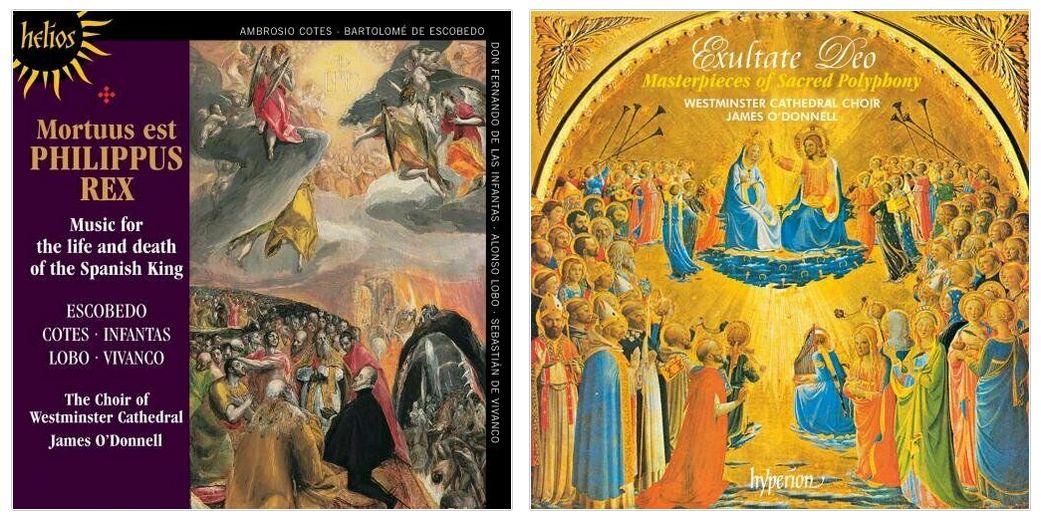

Music. His first recordings as organist (with the choir) soon appeared,

as Hyperion issued Victoria's Missa Vidi Speciosam (1984) and a recording

of works by Francisco Guerrero and other Spanish composers entitled Treasures

of the Spanish Renaissance (1985).

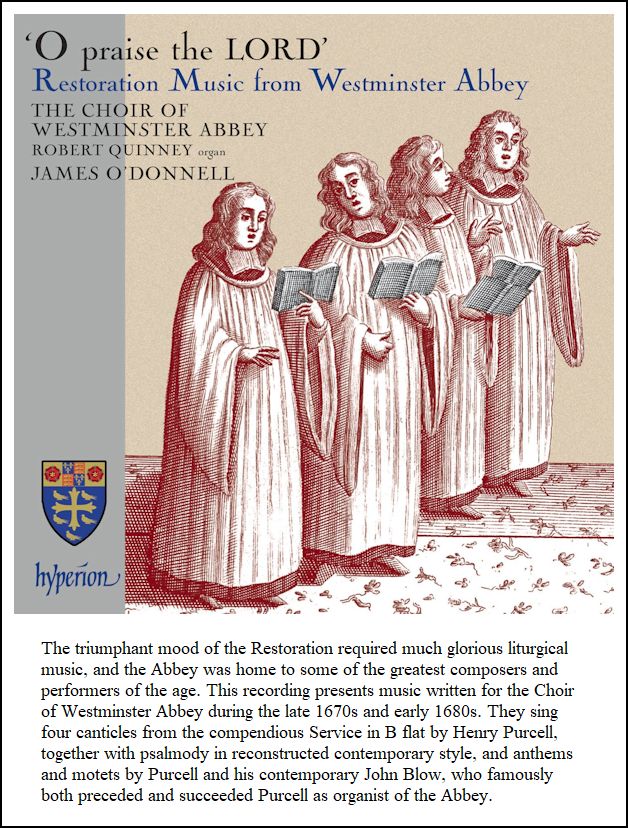

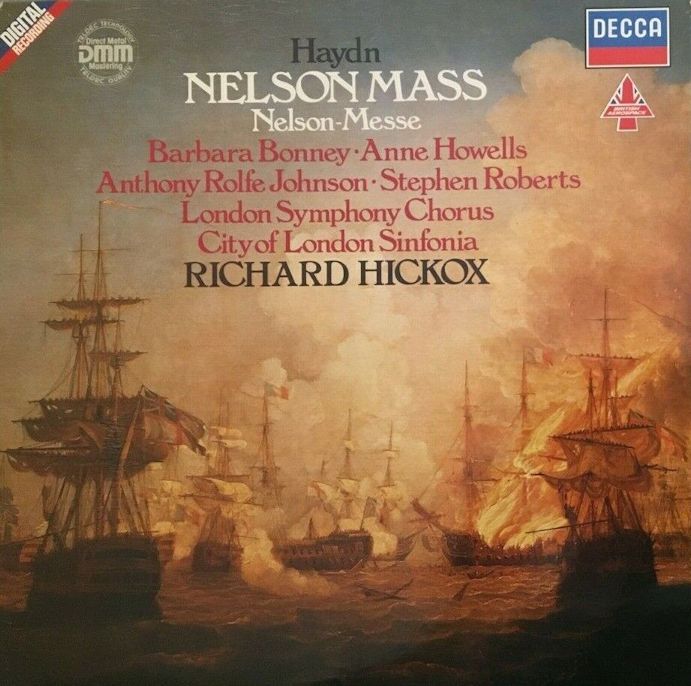

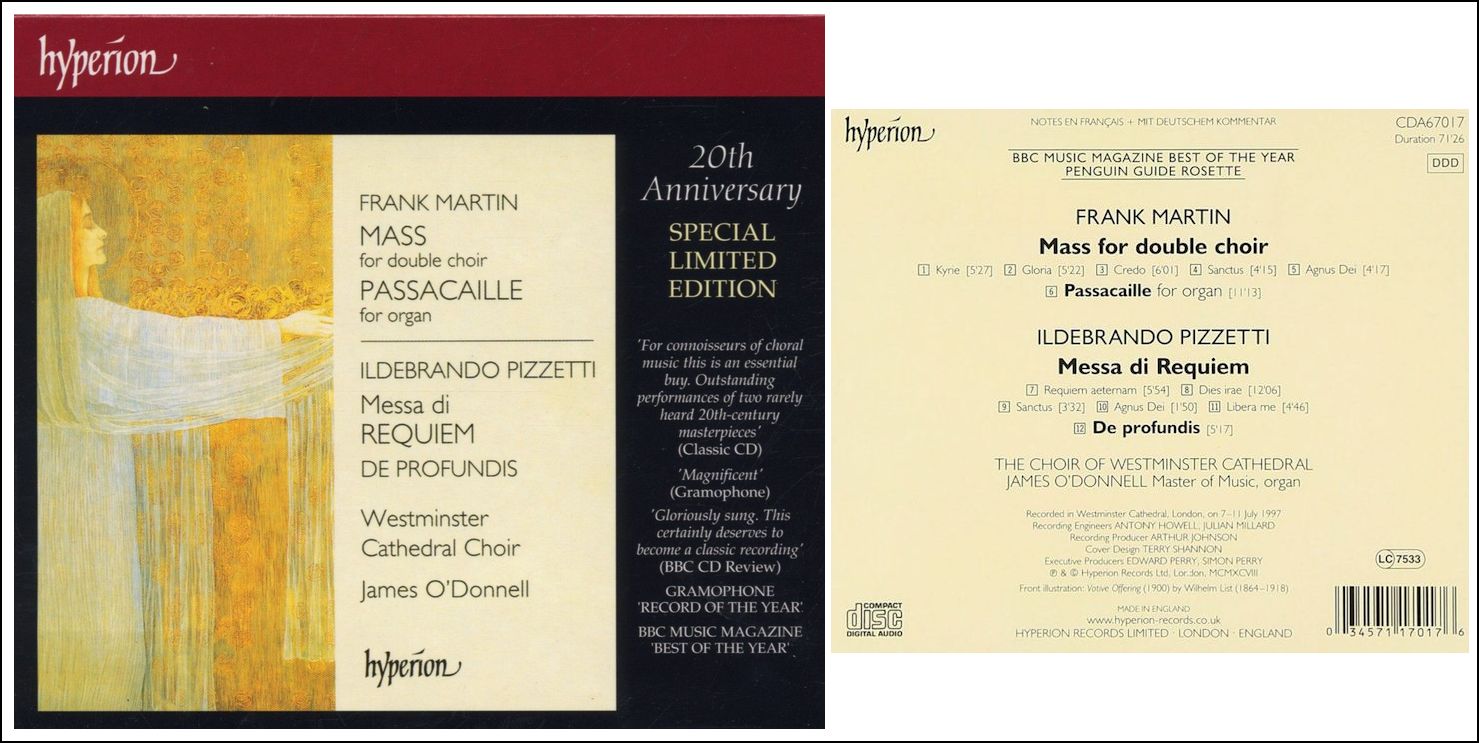

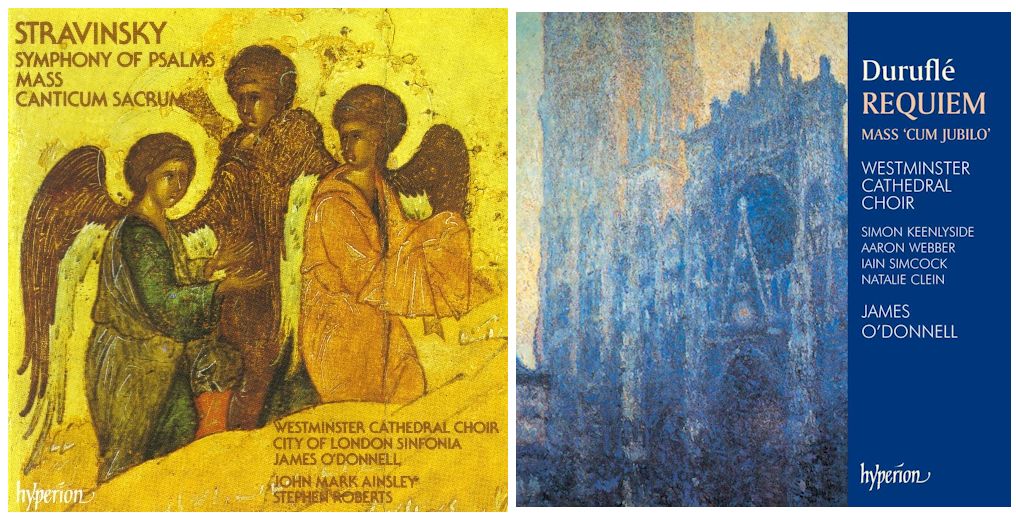

In 1988, O'Donnell assumed the post of Master of Music at Westminster Cathedral, thus taking control of the renowned choir. He frequently led them in concerts and concert broadcasts over both television and radio. He also made numerous acclaimed recordings with the choir, including Stravinsky's Symphony of Psalms (1990) and Duruflé's Requiem (1994). In 1997, O'Donnell accepted the appointment as professor of organ at the Royal Academy of Music and in 2000 accepted a post at Westminster Abbey as director of daily choral services and music at state occasions. The post also included leadership of the Abbey Choir in its concerts, recordings, and tours throughout Europe, Japan, Australia, and the United States. As a conductor, O'Donnell has often worked with period-instrument ensembles such as the Hanover Band and the Orchestra of the Age of Enlightenment. As a keyboard soloist or continuo player, he has frequently appeared with the Gabrieli Consort and the King's Consort. He served as president of the Royal College of Organists from 2011 through 2013.

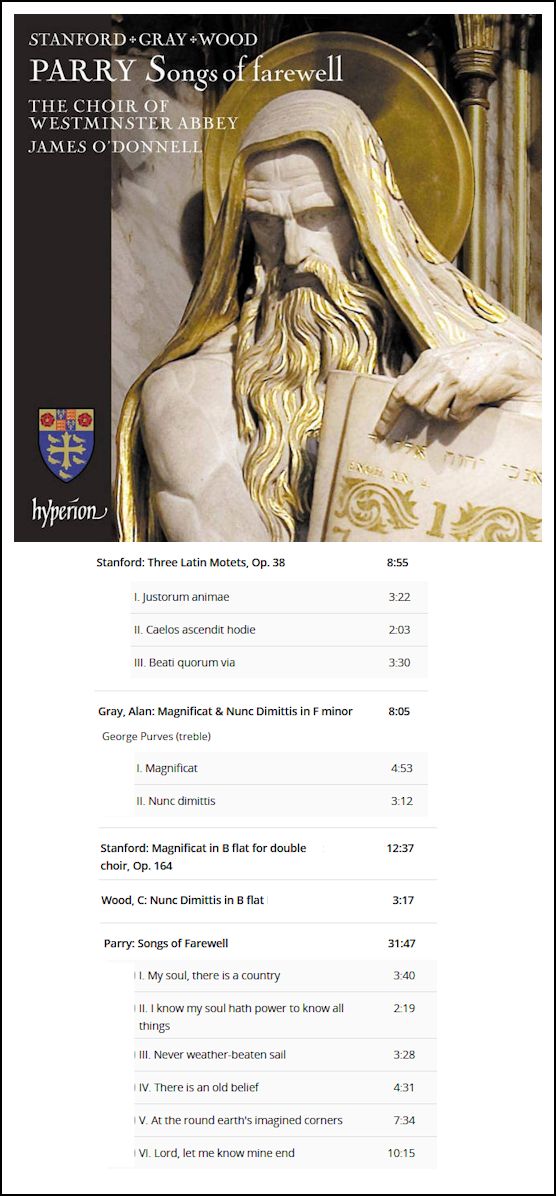

Though O'Donnell has mostly recorded for the Hyperion label, he's also been heard on Chandos, Decca, and Signum Classics, among others. His recordings with the Westminster Abbey Choir include a 2006 Hyperion release of Elgar works, Great Is the Lord, an album of works by Christopher Tye in 2012, and in 2020, a recording of Hubert Parry's Songs of Farewell.

== The link in this box refers to my interview elsewhere on my website. BD