Perry with his MBE

[Member of the Most Excellent Order of the British Empire]

Awarded by Queen Elizabeth II in 1990

for Services to Music

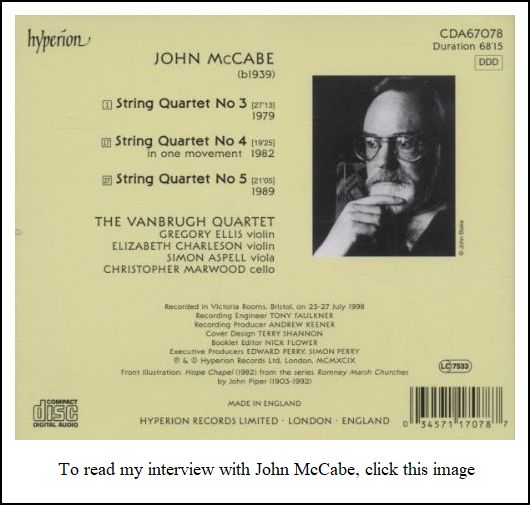

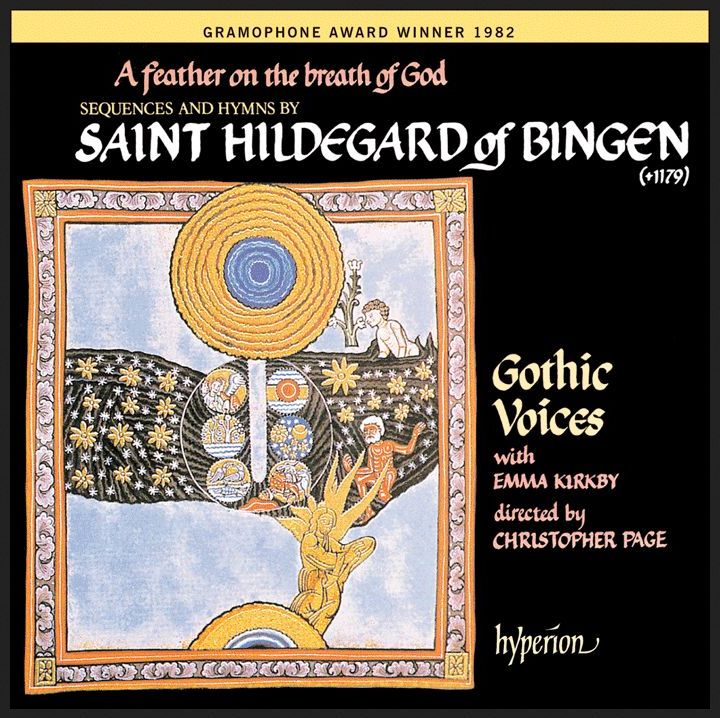

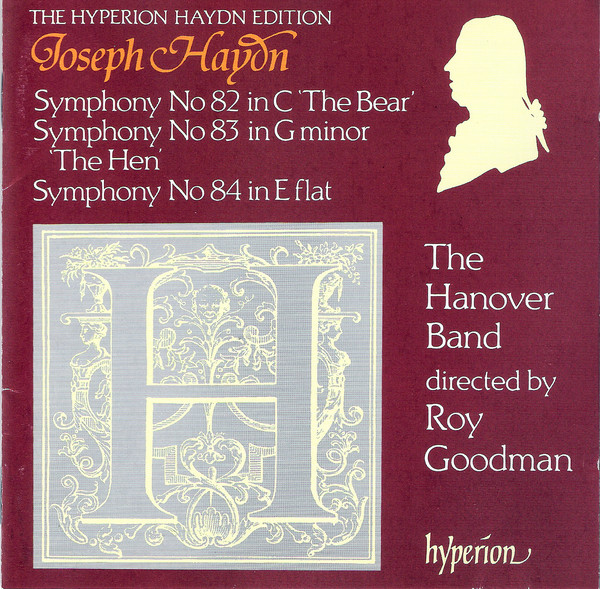

Ted PerryTed Perry, who died on Sunday aged 71, founded Hyperion, the independent British classical music label. At a time when the larger companies are concentrating on middle-of-the-road money-spinners - "crossover music", popular versions of the classics, and a handful of glamorous superstars - Hyperion has remained an oasis of integrity and idealism for the small, but devoted, clique of classical listeners who are no longer the focus of the large labels. Hyperion (named after the father of the muses) was launched in March 1980 when Perry, a former record store assistant, took out a £12,000 loan to record what he described as "nice records, records that need to be made, that no one else will make" on his own label. Hyperion quickly established itself as a label with a taste for the unusual. Among its earliest recordings were the Finzi and Stanford Clarinet Concertos, played by Thea King and the Philharmonia Orchestra under Alun Francis, and an organ transcription of Mussorgsky's Pictures at an Exhibition, performed by Arthur Wills. It soon won a following among collectors, both for its interest in neglected British composers, early Romantics and medieval and Baroque works, and for its fine production standards. For several years, the label struggled to break even, so Perry drove minicabs at night and dragooned his family into packaging discs round the kitchen table. But things changed for the better when the company released Sacred Vocal Music of Monteverdi (with the soprano Emma Kirkby, the tenor Ian Partridge and the bass David Thomas) and, even more profitably, a collection of works by the 12th-century abbess Hildegard of Bingen. Perry's success was built on recognising the existence of a small

but dependable market for well-performed, stylishly packaged recordings

of music that fall outside the core of potboilers which are over-represented

in the catalogues of the major classical labels. Though he could never

afford to record huge symphonic works with big-name conductors, he

proved that record companies could prosper by skillful exploitation of

a niche market. As one music critic put it: "Hyperion has an extraordinary

gift for detecting repertoire which leaves us wondering how we ever lived

without it."

Perry went on to build Hyperion and its subsidiary label Helios

(Helios, the sun, was the son of Hyperion) into the largest independent

classical label in the country, with a catalogue of some 1,200 titles.

As well as the label's more recondite recordings, Hyperion also produced

a 36-disc collection of the complete Schubert Lieder, with the pianist

Graham Johnson accompanying many of the leading Schubert singers of the

past 20 years, and Leslie Howard's survey of Liszt's solo piano music,

which took 14 years to record and ran to 95 discs. In addition, there

were series of Henry Purcell, the masses of John Taverner, the church music

of John Sheppard and the music of Robert Simpson.

[See my interview with Ann Murray]

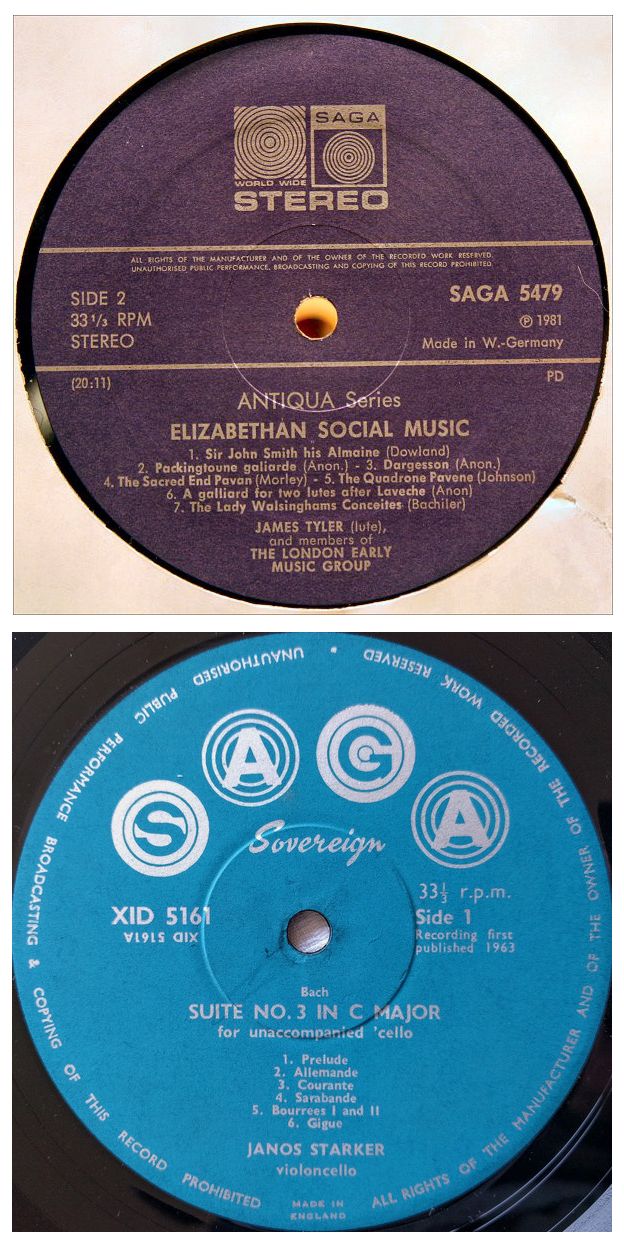

George Edward Perry was born into a working-class family on May 15 1931. He developed a fascination with music after a childhood hip operation left him in leg braces and unable to participate in sports. After leaving school, he was taken on as a buyer at EMG Handmade Gramophones, "a gentleman's record shop" in Soho Square. When Deutsch Grammophon opened a London office in 1956, Perry oversaw its first British releases. But the following year, he moved to Sydney, Australia, to run marketing and distribution at Festival Records. He returned to London in 1961 and joined Saga, a small British label,

as its director of artists and repertory. He left the company in 1963, but

returned in 1972. In the mid-1970s he left Saga again to start Meridian

Records with John Shuttleworth. In 1980 he left Meridian to start Hyperion

with his wife, Doreen, and a financial partner, Bill Singer.

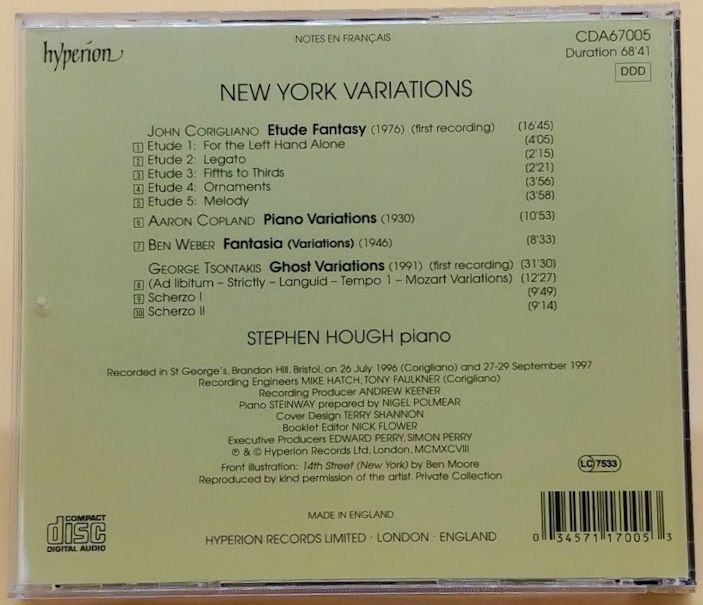

[If you look very closely, Perry's name appears as

Executive Producer in the lower-left]

Perry's loyalty to his performers was a byword: artists such as the King's Consort, Elizabeth Wallfisch, Sir Charles Mackerras, Emma Kirkby, Gothic Voices, Graham Johnson and Thea King became Hyperion "regulars". Under Perry's leadership, Hyperion won many awards and accolades from the serious end of the classical music press; in January 1996, the company was presented with the Best Label Award at the Cannes Classiques Awards. Ted Perry's marriage was dissolved in 1981. He is survived by a son

and two daughters.

-- Note that links in this box and below refer

to my interviews elsewhere on my website. BD

|

| The compact disc is an evolution of LaserDisc

technology, where a focused laser beam is used that enables the high

information density required for high-quality digital audio signals.

Prototypes were developed by Philips and Sony independently in the late

1970s. Although originally dismissed by Philips Research management as

a trivial pursuit, the CD became the primary focus for Philips as the LaserDisc

format struggled. In 1979, Sony and Philips set up a joint task force

of engineers to design a new digital audio disc. After a year of experimentation

and discussion, the Red Book CD-DA standard was published

in 1980. After their commercial release in 1982, compact discs and their

players were extremely popular. Despite costing up to $1,000, over 400,000

CD players were sold in the United States between 1983 and 1984. By 1988,

CD sales in the United States surpassed those of vinyl LPs, and by 1992

CD sales surpassed those of prerecorded music cassette tapes. The success

of the compact disc has been credited to the cooperation between Philips

and Sony, which together agreed upon and developed compatible hardware.

The unified design of the compact disc made it so consumers could purchase

any disc or player from any company, and allowed the CD to dominate the

at-home music market unchallenged. The new audio disc was enthusiastically received, especially in the early-adopting classical music and audiophile communities, and its handling quality received particular praise. As the price of players gradually came down, and with the introduction of the portable Discman, the CD began to gain popularity in the larger popular and rock music markets. With the rise in CD sales, pre-recorded cassette tape sales began to decline in the late 1980s. CD sales overtook cassette sales in the early 1990s. The CD was planned to be the successor of the vinyl record for playing music, rather than primarily as a data storage medium. From its origins as a musical format, CDs have grown to encompass other applications. In 1983, following the CD's introduction, Immink and Braat presented the first experiments with erasable compact discs during the 73rd AES Convention. In June 1985, the computer-readable CD-ROM (read-only memory) and, in 1990, CD-Recordable were introduced, also developed by both Sony and Philips. Recordable CDs were a new alternative to tape for recording music and copying music albums without defects introduced in compression used in other digital recording methods. Other newer video formats such as DVD and Blu-ray use the same physical geometry as CD, and most DVD and Blu-ray players are backward compatible with audio CD. U.S. CD sales peaked in 2000. By the early 2000s, the CD player had largely replaced the audio cassette player as standard equipment in new automobiles, with 2010 being the final model year for any car in the United States to have a factory-equipped cassette player. With the increasing popularity of portable digital audio players, such as mobile phones, and solid state music storage, CD players are being phased out of automobiles in favor of minijack auxiliary inputs, wired connection to USB devices and wireless Bluetooth connection. Meanwhile, with the advent and popularity of Internet-based distribution of files in lossily-compressed audio formats such as MP3, sales of CDs began to decline in the 2000s. For example, between 2000 and 2008, despite overall growth in music sales and one anomalous year of increase, major-label CD sales declined overall by 20 percent, although independent and DIY music sales may be tracking better according to figures released 30 March 2009, and CDs still continue to sell greatly. As of 2012, CDs and DVDs made up only 34 percent of music sales in the United States. By 2015, only 24 percent of music in the United States was purchased on physical media, ⅔ of this consisting of CDs; however, in the same year in Japan, over 80 percent of music was bought on CDs and other physical formats. In 2018, U.S. CD sales were 52 million units — less than 6% of the peak sales volume in 2000. |

Perry: A lot of people like CDs,

and they seem to buy them in very moderate quantities.

Perry: A lot of people like CDs,

and they seem to buy them in very moderate quantities. Perry: To make nice records, as many as feasible, and

practical, and possible — without

making a misery for myself — and to

make them to as high a quality as possible, and spread a little bit of joy

and light throughout the world. Seriously, that’s what gives me

kicks. I just love making nice records for people to enjoy.

Perry: To make nice records, as many as feasible, and

practical, and possible — without

making a misery for myself — and to

make them to as high a quality as possible, and spread a little bit of joy

and light throughout the world. Seriously, that’s what gives me

kicks. I just love making nice records for people to enjoy.|

The Vinyl revival is the renewed interest and increased sales of vinyl records, or gramophone records, that has been taking place in the Western world since about 2007. The analogue format made of polyvinyl chloride had been the main vehicle for the commercial distribution of pop music from the 1950s until the 1980s and 1990s when they were largely replaced by the Compact Disc (CD). Since the turn of the millennium, CDs have been partially replaced by digital downloads and streaming services. However, in 2007, vinyl sales made a sudden small increase, starting its comeback, and by the early 2010s it was growing at a very fast rate. In some territories, vinyl is now more popular than it has been since the late 1980s, though vinyl records still make up only a marginal percentage (<6%) of overall music sales. Along with steadily increasing vinyl sales, the vinyl revival is

also evident in the renewed interest in the record shop (as seen by the creation

of the annual worldwide Record Store Day), the implementation of music

charts dedicated solely to vinyl, and an increased output of films (largely

independent) dedicated to the vinyl record and culture. In 1988, the Compact Disc surpassed the gramophone record in popularity in Canada and the U.S. Vinyl records experienced a sudden decline in popularity between 1988 and 1991, when the major label distributors restricted their return policies, which retailers had been relying on to maintain and swap out stocks of relatively unpopular titles. First, the distributors began charging retailers more for new product if they returned unsold vinyl, and then they stopped providing any credit at all for returns. Retailers, fearing they would be stuck with anything they ordered, only ordered proven, popular titles that they knew would sell, and devoted more shelf space to CDs and cassettes. Record companies also deleted many vinyl titles from production and distribution, further undermining the availability of the format and leading to the closure of pressing plants. This rapid decline in the availability of records accelerated the format's decline in popularity, and is seen by some as a deliberate ploy to make consumers switch to CDs, which were more profitable for the record companies. But ever since 2007, the popularity of vinyl records has risen again. The largest online retailer of vinyl records in 2014 was Amazon with a 12.3% market share, while the largest physical retailer of vinyl records was Urban Outfitters with an 8.1% market share. In its 'Shipment and Revenue Statistics' report for 2016, the Recording Industry Association of America noted that "Shipments of vinyl albums were up 4% to $430 million, and comprised 26% of total physical shipments at retail value – their highest share since 1985". In 2019, Rolling Stone said that "Vinyl records earned $224.1 million (on 8.6 million units) in the first half of 2019, closing in on the $247.9 million (on 18.6 million units) generated by CD sales. Vinyl revenue grew by 12.8% in the second half of 2018 and 12.9% in the first six months of 2019, while the revenue from CDs barely budged. If these trends hold, records will soon be generating more money than compact discs". Best Buy discontinued CDs in 2019, but as of January 2020 still sells vinyl. Target Corporation and Walmart still sell CDs, but use less shelf space for them and use more space for vinyl records, players, and accessories. Similarly in the United Kingdom, the compact disc surpassed the gramophone record in popularity in the late 1980s. This started a gradual decline in vinyl record sales throughout the 1990s. Sales of vinyl LP records in the UK increased every year between 2007 and 2014 In December 2011, BBC Radio 6 Music began an occasional Vinyl Revival series in which Peter Paphides met musicians who revealed, and played selections from, their vinyl record collections. In November 2014, it was reported that over one million vinyl records had been sold in the UK since the beginning of the year. Sales had not reached this level since 1996. The British Phonographic Industry (BPI) predicted that Christmas sales would bring the total for the year to around 1.2 million. However, vinyl sales were still a very small proportion of total music sales. Pink Floyd’s The Endless River became the fastest-selling UK vinyl release of 2014 – and the fastest-selling since 1997 – despite selling only 6,000 copies. In 2016, 3.2 million vinyl records were sold in the UK, the best sale for a quarter of a century. As of 2016 the revival continued, with UK vinyl sales exceeding streaming audio revenue for the year. In January 2017, the BPI's 'Official UK recorded music market report for 2016', using Official Charts Company data, noted that "Though still niche in terms of its size within the overall recorded music market, vinyl enjoyed another stellar year, with over 3.2 million LPs sold – a 53 per cent rise on last year". The BPI also reported that "The biggest-selling vinyl artist was David Bowie, with 5 albums posthumously featuring in the top-30 best-sellers, including his Mercury Prize shortlisted Blackstar, which was 2016’s most popular vinyl recording ahead of Amy Winehouse’s Back To Black, selling more than double the number of copies of 2015’s best seller on vinyl – Adele’s 25". BBC Radio 4's Front Row discussed the increase in coloured vinyl releases in October 2017 in the wake of recent albums in the format by Beck, Liam Gallagher, and St. Vincent. The price and size of CDs are part of why they became unpopular. A $15-20 CD comes in a small case and both are flimsy. A vinyl record is slightly more expensive but is more durable, and comes with album cover art, liner notes, and perhaps a poster or t-shirt. Used records are inexpensive. In a comparison of analog and digital recording, vinyl's analog imperfection adds warmth to sound that listeners enjoy. CDs compress stored sound, dulling high and low notes unlike vinyl, and listeners likely prefer streaming audio if they accept the compression. Though many sales in vinyl are of modern artists with modern styles or genres of music, the revival has sometimes been considered to be a part of the greater revival of retro style, since many vinyl buyers are too young to remember vinyl being a primary music format. |

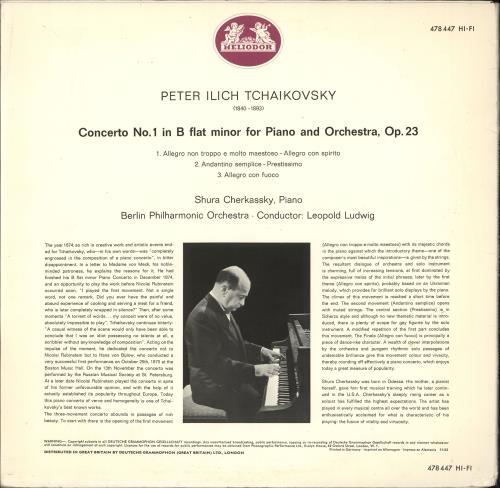

Perry: No. Deutsche Grammophon

in those days, believe it or not, was a virtually unknown label.

It was a parochial German record label. We’d never even

seen one in England. We knew vaguely there was something called

DGG. Polydor was a quite well-known name, though the actual Polydor

label was not very well known. They had been pressed by Decca.

They were known as Decca-Polydor, and we knew they hailed from some splendid

German record company. In 1956 they decided to open an office in

London, and it was called the Heliodor Record Company. They started

with their archive, and they decided they needed somebody who understood

the English tastes. In other words, they wanted somebody to advise

them what of their catalogue would sell in England. I was able to

say yes, that they could sell Shura Cerkassky doing the Tchaikovsky B-Flat

Piano Concerto quite well, but they wouldn’t be able to sell many copies

of Zar und Zimmermann by Lortzing. So, in fact, that’s what

I did for a couple of years.

Perry: No. Deutsche Grammophon

in those days, believe it or not, was a virtually unknown label.

It was a parochial German record label. We’d never even

seen one in England. We knew vaguely there was something called

DGG. Polydor was a quite well-known name, though the actual Polydor

label was not very well known. They had been pressed by Decca.

They were known as Decca-Polydor, and we knew they hailed from some splendid

German record company. In 1956 they decided to open an office in

London, and it was called the Heliodor Record Company. They started

with their archive, and they decided they needed somebody who understood

the English tastes. In other words, they wanted somebody to advise

them what of their catalogue would sell in England. I was able to

say yes, that they could sell Shura Cerkassky doing the Tchaikovsky B-Flat

Piano Concerto quite well, but they wouldn’t be able to sell many copies

of Zar und Zimmermann by Lortzing. So, in fact, that’s what

I did for a couple of years. BD: How long did you stay in New South Wales?

BD: How long did you stay in New South Wales?|

Originally founded in 1980 by the scholar and musician Christopher

Page, Gothic Voices has gone on to record twenty-five albums,

three of which won the coveted Gramophone Early Music Award.

Its first recording A feather on the breath of God – Sequences

and Hymns by Saint Hildegard of Bingen still remains one of the best-selling

recordings of pre-Classical music ever made.

In the UK they have performed at the Aldeburgh and Chester Festivals, the York and Birmingham Early Music Festivals and at the International Festivals of Edinburgh and Cheltenham. They have toured widely throughout Europe, appearing at the Flanders, Utrecht and Stuttgart Early Music Festivals and the Vestfold Festival in Norway. They have also appeared in Israel and in the Americas. Gothic Voices also enjoy performing contemporary music, particularly pieces with medieval associations. Many of today's composers are influenced by medieval repertoire and its often experimental nature. The group plans to give a renewed emphasis to the combination of old and new alongside its more traditional programmes. Gothic Voices is committed to bringing medieval music into the

mainstream. Their imaginative programmes aim to use their voices in varying

combinations to produce performances of great beauty and thereby to continue

to win the appreciation of audiences all over the world. * * *

* *

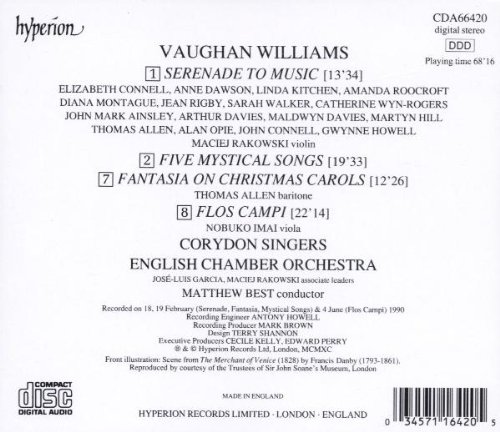

Founded by Matthew Best in 1973, Corydon Singers are now widely recognised as one of the foremost choirs in Britain. Their first Hyperion recording, of Bruckner motets, was issued in 1983 and established them on the road to distinction. Their subsequent and numerous recordings, all for Hyperion, have consistently earned the approval of the press in Britain, Europe, the United States, Japan and elsewhere. Their 1990 recording of Vaughan William’s Serenade to Music and other works was selected as Record of the Year by both The Guardian and The Sunday Times, and was nominated for a Brit Award. Their recording of Rachmaninov’s Vespers was chosen as the preferred version in BBC Radio 3’s ‘Building a Library’ and their recording of Bruckner’s Te Deum and Mass in D minor was selected as one of the top releases of 1993 by the BBC’s Record Review. A great many of Corydon’s recordings have reached the Gramophone Awards short list in the choral section and they have four times been runner-up: in 1984 with Howells’s Requiem, 1990 with Vaughan Williams’s Serenade, 1996 Berlioz’s L’Enfance du Christ and in 1997 with Beethoven early cantatas. -- The text of each précis in this

box and the one below is from the Hyperion Website

|

Perry: Yes. I was there between 1961 until November,

1963, which was the month that President Kennedy was assassinated.

It’s a period I remember vividly. Then I moved onto a period that

I don’t feel at all happy about, because I left the record business.

I had a growing family, and the record business didn’t pay a large

amount of money — at least in England

it didn’t in those days — and I needed

to educate three young children.

Perry: Yes. I was there between 1961 until November,

1963, which was the month that President Kennedy was assassinated.

It’s a period I remember vividly. Then I moved onto a period that

I don’t feel at all happy about, because I left the record business.

I had a growing family, and the record business didn’t pay a large

amount of money — at least in England

it didn’t in those days — and I needed

to educate three young children.|

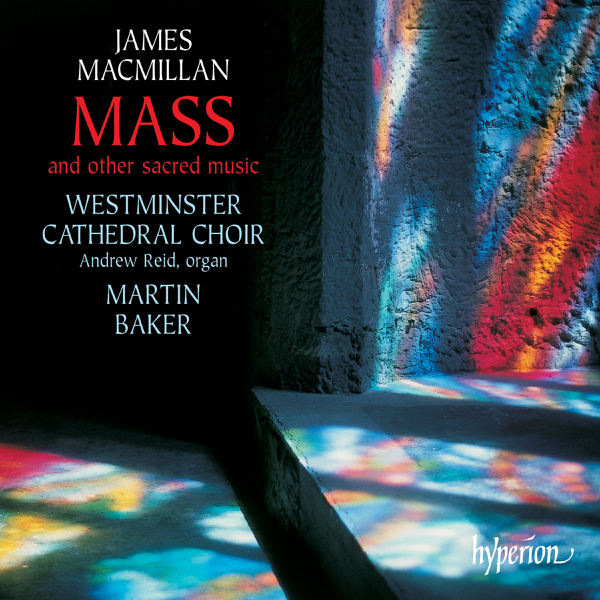

The establishment of a fine choral foundation was part of the original vision of the founder of Westminster Cathedral, Cardinal Herbert Vaughan. Vaughan laid great emphasis on the beauty and integrity of the new Cathedral’s liturgy and music, and realised that a residential choir school for the boy choristers was essential to the realisation of his vision. Daily sung Masses and Offices were immediately established when the Cathedral opened in 1903, and have continued without interruption ever since. Today, Westminster Cathedral Choir is the only professional Catholic choir in the world to sing a daily Mass. Richard Runciman Terry, the Cathedral’s first Master of Music, proved to be an inspired choice. Terry was both a brilliant choir trainer and a pioneering scholar, one of the first musicologists to revive the great works of the English and Continental Renaissance composers. Terry built Westminster Cathedral Choir’s reputation on performances of music—by Byrd, Tallis, Taverner, Palestrina and Victoria, among others—that had not been heard since the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, and Mass at the Cathedral was soon attended by inquisitive musicians as well as the faithful. The performance of great Renaissance masses and motets in their proper liturgical context remains the cornerstone of the choir’s activity. George Malcolm consolidated the musical reputation of Westminster

Cathedral Choir during his time as Master of Music—in particular through

the now legendary recording of Victoria’s Tenebrae Responsories.

More recent holders of the post have included Colin Mawby, Stephen Cleobury,

David Hill and James O’Donnell. The choir continues to thrive under the

current Master of Music, Martin Baker, who has held the post since February

2000.

In addition to its performances of Renaissance masterpieces, Westminster Cathedral Choir has given many first performances of music written especially for it by contemporary composers. Terry gave the premieres of music by Vaughan Williams (whose Mass in G minor received its first public performance at a Mass in the Cathedral), Gustav Holst, Herbert Howells and Charles Wood; in 1959 Benjamin Britten wrote his Missa brevis for the choristers; and since 1960 works by Lennox Berkeley, William Mathias, Colin Mawby and Francis Grier have been added to the repertoire. Most recently three new Masses—by Roxanna Panufnik, James MacMillan and Sir Peter Maxwell Davies—have been performed and recorded by the choir. Westminster Cathedral Choir made its first acoustic recording in 1907. Many more have followed, most recently the acclaimed series on the Hyperion label, and many awards have been conferred on the choir’s recordings. Of these the most prestigious are the 1998 Gramophone Awards for both ‘Best Choral Recording of the Year’ and ‘Record of the Year’, for the performance of Martin’s Mass for Double Choir and Pizzetti’s Requiem. It is the only cathedral choir to have won in either of these categories. When its duties at the Cathedral permit, the choir also gives concert performances both at home and abroad. It has appeared at many important festivals, including Aldeburgh, Salzburg, Copenhagen, Bremen and Spitalfields. It has appeared in many of the major concert halls of Britain, including the Royal Festival Hall, the Wigmore Hall and the Royal Albert Hall. The Cathedral Choir also broadcasts frequently on radio and television. * * *

* *

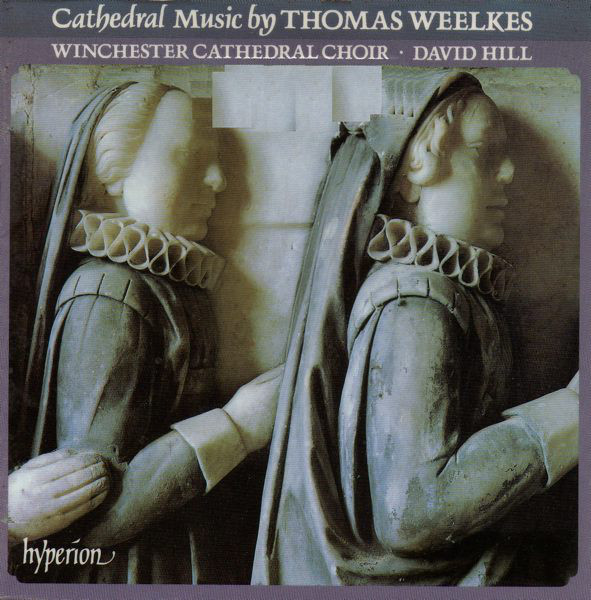

The Choir of Winchester Cathedral is recognised as one of Britain's leading Cathedral choirs. Their principal function is the singing of services in Winchester Cathedral, and, during term time, they sing an average of eight services each week. In addition they give concerts both in the Cathedral and elsewhere in Britain. They have also toured the USA, Australia and Brazil as well as most European countries. They are regular broadcasters on radio and television. Their repertoire ranges from music in the Winchester Troper (dating from c1000 AD) to many contemporary composers. Winchester Cathedral has also been at the forefront of commissioning new works from composers such as John Tavener, Jonathan Harvey, James Macmillan and Tarik O’Regan. Their many recordings for Hyperion, Virgin Classics and Decca include

discs of English music by Purcell, Tye, Tallis, Stanford, and Elgar.

Other recordings for Herald and Regent include collections of music for

Advent, Christmas and Epiphany.

The Choir comprises eighteen boy choristers and twelve permanent

lay clerks. The choristers are educated at The Pilgrims' School where

they all learn at least one instrument, and the majority of them gain

music scholarships to their next school. The lay clerks are all experienced

musicians who work in a wide variety of professions, including teaching,

PR and administration. The Cathedral also runs a girls’ choir (who are

aged from 12-17) who sing services and concerts both by themselves and

with the boys and Lay Clerks. * * * *

* The Sixteen is recognized as one of the world’s greatest ensembles. Comprising both choir and period-instrument orchestra, The Sixteen’s total commitment to the music it performs is its greatest distinction. A special reputation for performing early English polyphony, masterpieces of the Renaissance, bringing fresh insights into Baroque and early Classical music and a diversity of 20th- and 21st-century music, is drawn from the passions of Founder and Conductor Harry Christophers CBE. At home in the UK The Sixteen are ‘The Voices of Classic FM’ and Associate Artists of The Bridgewater Hall, Manchester. The group promotes The Choral Pilgrimage, an annual tour of the UK’s finest cathedrals which aims to bring music back to the buildings for which it was written. The Sixteen features in the highly successful BBC television series, Sacred Music, presented by actor Simon Russell Beale – the latest hour-long programme was aired in December 2011, marking the 400th anniversary of the death of the Spanish composer Tomás Luis de Victoria. The Sixteen tours throughout Europe, Asia, Australia and the Americas

and has given regular performances at major concert halls and festivals

worldwide, including the Barbican Centre (London), The Bridgewater Hall

(Manchester), Cité de la musique (Paris), Concertgebouw (Amsterdam)

and Sydney Opera House. Festival appearances include the BBC Proms, Hong

Kong, Wellington, Granada, Lucerne, Edinburgh, Istanbul, Prague, Bremen,

La Chaise Dieu and Salzburg.

Since 2001 The Sixteen has been building its own record label, Coro, which released its 100th title in spring 2012. Bringing together live concerts and recording plans has allowed The Sixteen to develop a glittering catalogue of releases, containing music from the Renaissance and Baroque through to great works of our time. In 2011 the group launched Genesis Sixteen, a new training programme for young singers. Aimed at 18- to 23-year-olds, this is the UK’s first fully-funded choral programme for young singers designed specifically to bridge the gap from student to professional practitioner. |

Perry: No, we generally finish the

series. I’m delighted to say many of the artists whom we record

do remain, if not exclusive, they’re certainly loyal. They don’t

storm off and record for thousands of other labels. There are some

exceptions, and it usually depends on their ideas and ambitions. For

instance, The Sixteen, which is a very fine English choir, started off by

recording the early English polyphonic repertoire

— people like John Taverner (c. 1490-1545) [not to be

confused with John Tavener (1944-2013)], Robert Fayrfax (1464-1521),

and so on. But they also want to do baroque, and even twentieth-century

music. They want to do Poulenc, and that territory is being

done for us by another choir, the Corydon Singers. So, I have to

tell Harry Christophers of The Sixteen, sorry. We’ll continue with

the early stuff but, if you don’t mind, I won’t do Poulenc. So Harry

feels free to go and approach another label, and therefore it comes out

on Virgin, or Collins Classics.

Perry: No, we generally finish the

series. I’m delighted to say many of the artists whom we record

do remain, if not exclusive, they’re certainly loyal. They don’t

storm off and record for thousands of other labels. There are some

exceptions, and it usually depends on their ideas and ambitions. For

instance, The Sixteen, which is a very fine English choir, started off by

recording the early English polyphonic repertoire

— people like John Taverner (c. 1490-1545) [not to be

confused with John Tavener (1944-2013)], Robert Fayrfax (1464-1521),

and so on. But they also want to do baroque, and even twentieth-century

music. They want to do Poulenc, and that territory is being

done for us by another choir, the Corydon Singers. So, I have to

tell Harry Christophers of The Sixteen, sorry. We’ll continue with

the early stuff but, if you don’t mind, I won’t do Poulenc. So Harry

feels free to go and approach another label, and therefore it comes out

on Virgin, or Collins Classics. BD: I assume you are personally involved,

as least to some extent, in every record that comes out under your label?

BD: I assume you are personally involved,

as least to some extent, in every record that comes out under your label? BD: That’s a good thing for everyone.

Do you find making records fun?

BD: That’s a good thing for everyone.

Do you find making records fun?This conversation was recorded in Chicago on September 25, 1990. Portions were broadcast on WNIB two months later. This transcription was made in 2020, and posted on this website at that time. My thanks to British soprano Una Barry for her help in preparing this website presentation.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website, click here.

Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM.

You are invited to visit his website for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.