A Conversation with Bruce Duffie

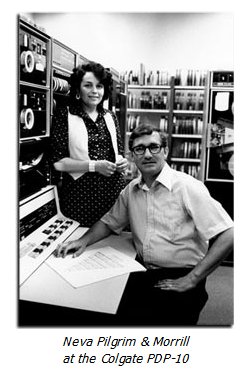

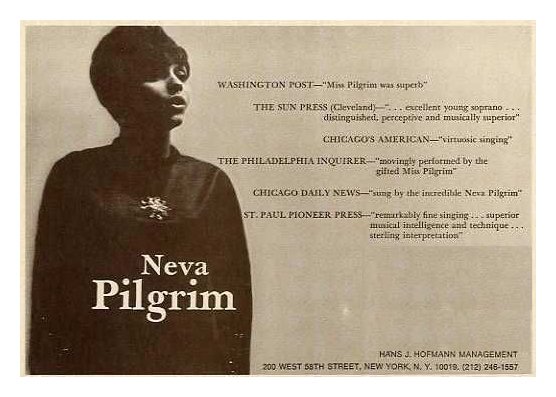

| Neva Pilgrim, soprano, a native

Minnesotan, graduated magna cum laude from Hamline University, received a

Master of Music from Yale, and studied at the Vienna Academy of Music on a

Ditson Fellowship. The recipient of a Martha Baird Rockefeller grant, NEA

and Fromm Foundation commission grants. [See my Interview with Paul Fromm.]

She has also received a Certificate of Merit for her significant

contribution to the field of music from the Yale School of Music, an outstanding

alumni award from Hamline University, and the Laurel Leaf Award from the American

Composers Alliance. Ms. Pilgrim is known throughout the country for her extensive

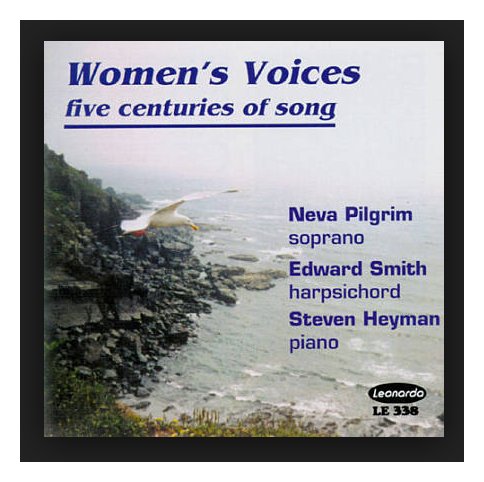

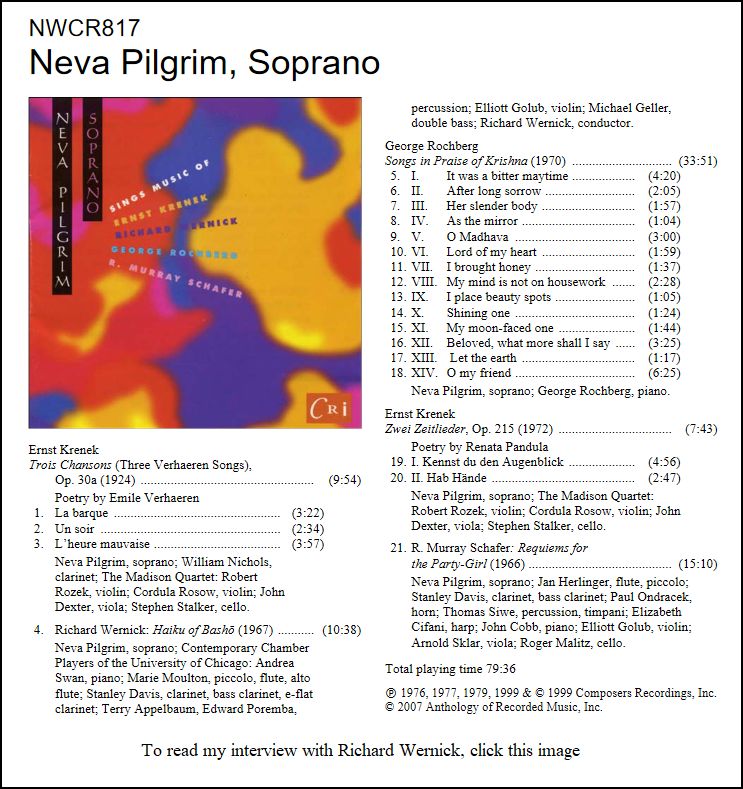

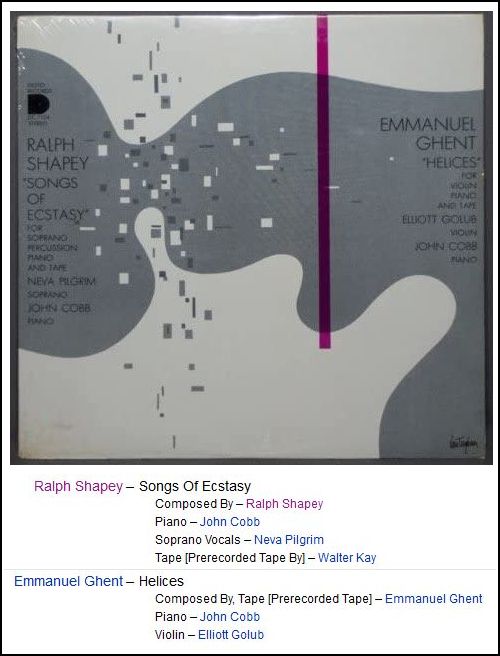

work with composers, many of whom have written for her. She appears regularly in recital and as soloist with orchestras, having performed with the Chicago Symphony, New York Philharmonic, Brooklyn Philharmonic, Syracuse Symphony, and Clarion Concerts. She has concertized in Japan, Canada and Europe and appeared at such festivals as Tanglewood, Marlboro, Chautauqua, Monadnock, and Saratoga Baroque, as well as the International Computer Music Festival. Neva Pilgrim has 19 recordings to her credit and has soloed with such distinguished chamber ensembles as the Da Capo Chamber Players; Speculum Musicae; the Baltimore Chamber Music Society; and the Concord, Tremont, and Madison Quartets, to name but a few. She is artist-in-residence in voice at Colgate University and maintains a private studio in New York City. -- Biography mostly from

the Leonarda Records website

|

NP: I try to find something that I think the general

audience would like. Every program for the radio is unique, different,

just as it would be if it were a concert program. It has to be something

very special. Every piece has to be good, but there must be a reason

to hang it all together. Tonight, for example, it’s classical music

with Yo-Yo Ma, and Mark O’Connor where they are doing crossover, you know,

bluegrass. Also the Kronos Quartet where they’re doing a little world

music that crosses over classical, and then a piece by a young composer that’s

viola with computer. That’s also crossover — acoustic and electronic.

To mix it up like that, I think, makes it more accessible to a general audience.

NP: I try to find something that I think the general

audience would like. Every program for the radio is unique, different,

just as it would be if it were a concert program. It has to be something

very special. Every piece has to be good, but there must be a reason

to hang it all together. Tonight, for example, it’s classical music

with Yo-Yo Ma, and Mark O’Connor where they are doing crossover, you know,

bluegrass. Also the Kronos Quartet where they’re doing a little world

music that crosses over classical, and then a piece by a young composer that’s

viola with computer. That’s also crossover — acoustic and electronic.

To mix it up like that, I think, makes it more accessible to a general audience. BD: When you are on stage, do you like being another

character?

BD: When you are on stage, do you like being another

character? BD: You’re

an American singer, obviously. Is there anything peculiarly American

about your technique or about your presentation?

BD: You’re

an American singer, obviously. Is there anything peculiarly American

about your technique or about your presentation? BD: Is it art or is it entertainment?

BD: Is it art or is it entertainment? NP:

Mmmmm, perhaps a little bit.

NP:

Mmmmm, perhaps a little bit.This interview was recorded at her home in Syracurse, NY, on August

22, 2003. Segments were used (with recordings) on WNUR in 2004 and 2013.

The transcription was made and posted on this website in 2013.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website, click here.

Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM, as well as on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio.

You are invited to visit his website for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.