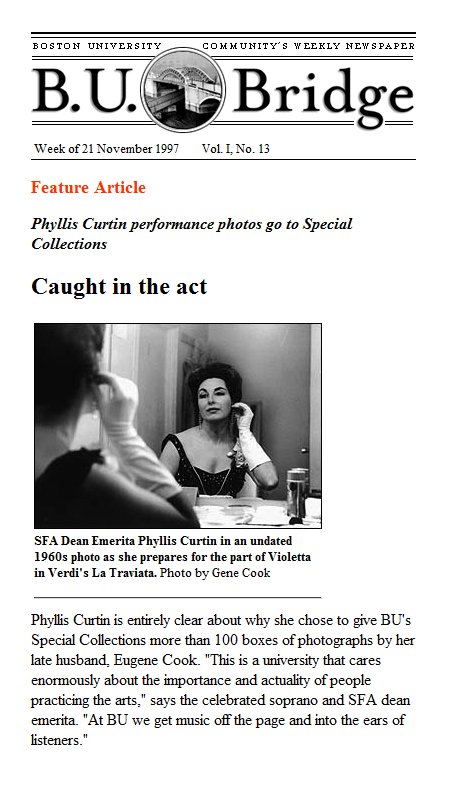

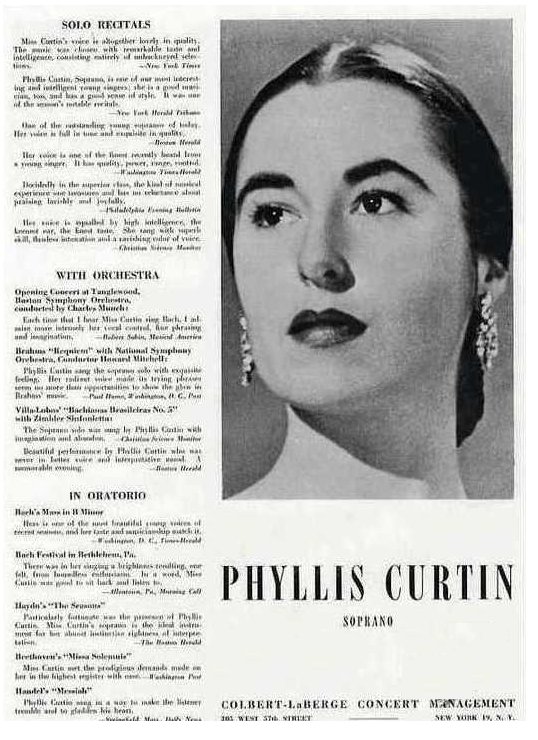

| Soprano Phyllis Curtin was born

in Clarksburg, WV, on December 3, 1921, graduated from Wellesley

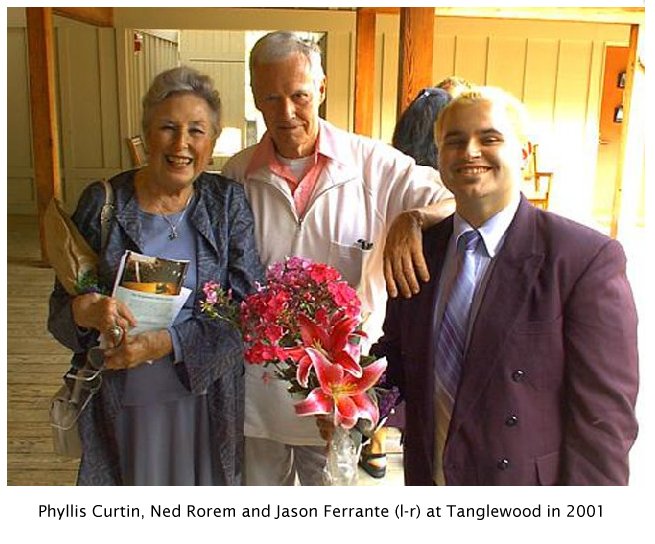

College, and in 1946 appeared at famed Tanglewood Music Center under

Leonard Bernstein and with the New England Opera under Boris Goldovsky.

She made her debut with the New York City Opera in 1953, where she sang

both classical and modern repertoire, including all major Mozart

heroines and many new works. Life magazine devoted three pages of

photos to her seductive ‘‘dance of the seven veils’’ in Richard

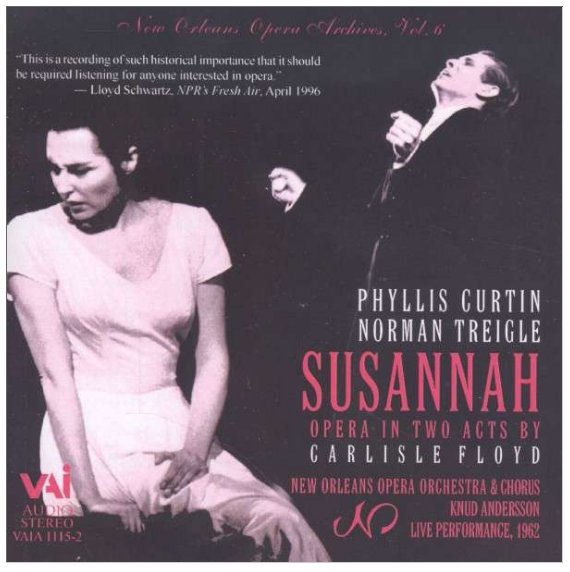

Strauss’s Salome in 1954. The following year she premiered the title

role in Carlisle Floyd’s Susannah, which she later sang at the Brussels

World’s Fair in 1958, followed by leading roles in premieres of Floyd’s

Wuthering Heights and The Passion of Jonathan Wade. More than 50 new

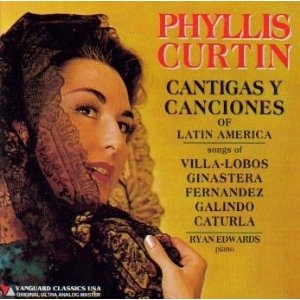

works were written expressly for her, including operas by Darius

Milhaud and Alberto Ginastera and a song cycle by Ned Rorem. She also

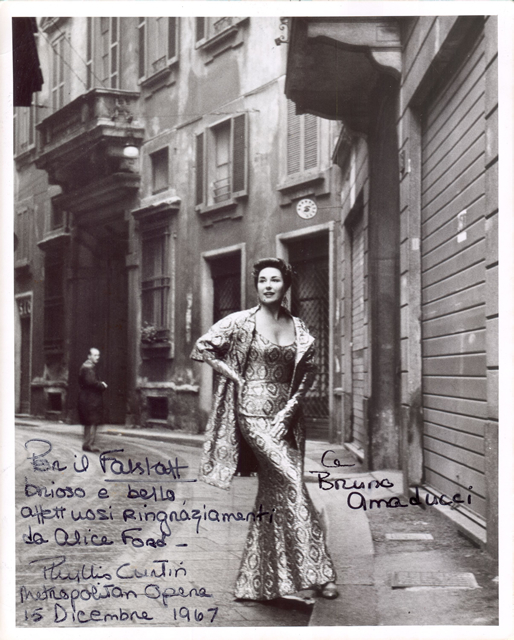

sang with the NBC Opera Company on television and on tour. Curtin made

her Metropolitan Opera debut in 1961 and developed an international

reputation with performances at the Teatro Colón in Buenos

Aires, La Scala in Milan, and the Vienna Staatsoper. Ms. Curtin became an artist-in-residence at the Tanglewood Music Center in 1964 and continues to teach there. At Yale University she taught voice, headed the opera program, and served as Master of Branford College. She became Dean of Boston University's College of Fine Arts in 1983 and Dean Emerita in 1992, continuing to teach singers and serving as Artistic Director of the Opera Institute, which she initiated in 1985. Master classes have taken her to many institutions in the United States and Canada, as well as to the Beijing Conservatory, the Tchaikovsky Conservatory in Moscow, the Tiblisi Conservatory, and the Britten-Pears School in Aldeburgh, England. In 1976, President Gerald Ford invited her to sing for a White House dinner honoring West German Chancellor Helmut Schmidt. Ms. Curtin served on the National Council for the Arts and in 1994 was designated a U.S. Ambassador for the Arts, a new honor given former council members. She has received Wellesley College's Alumnae Achievement Award and BU's College of Fine Arts Distinguished Faculty Award, and holds a number of honorary degrees in music and the humanities. |

Phyllis Curtin:

This was my fortieth year teaching at the Tanglewood Festival. As

a matter of fact, Tanglewood is the closest thing to a music school

that I have. I was a student here in 1946 when Boris Goldovsky

had an opera program here. [See my Interview with Boris

Goldovsky.] I came to that program in 1946, ’48, and ’51, and

since I had gone to Wellesley and majored in political science, this

was my music school.

Phyllis Curtin:

This was my fortieth year teaching at the Tanglewood Festival. As

a matter of fact, Tanglewood is the closest thing to a music school

that I have. I was a student here in 1946 when Boris Goldovsky

had an opera program here. [See my Interview with Boris

Goldovsky.] I came to that program in 1946, ’48, and ’51, and

since I had gone to Wellesley and majored in political science, this

was my music school. PC: It was by

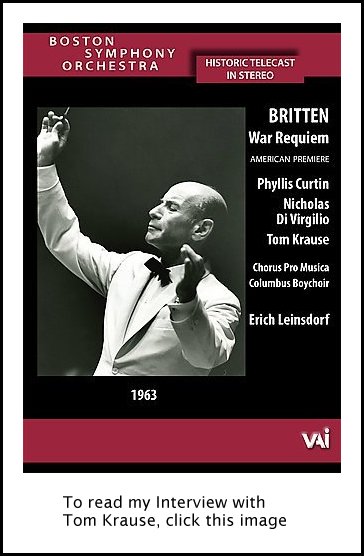

accident forty years ago. I was here to sing the American

premiere of the War Requiem

with the BSO. We did the first performances at Tanglewood, then

three or four in Boston and then in New York. It was a longer

rehearsal period than usual for things at the BSO in the summer.

Erich Leinsdorf was the conductor. [See my Interviews with Erich

Leinsdorf.] The opera program, which had been here for a very

long time, had been discontinued, and there were lots of rumors

around. I have no idea why, really, but there was no opera

program. They had a group of singers that had been brought up for

the summer, and I think it was Harry Kraut came to me and said,

“Phyllis, we have all these really unhappy singers. Can you think

of something to do?” I said, “I don’t really think so, but I

suppose we can sit around and talk about singing.” That’s how the

classes began, and they’ve been going on ever since. [Both

laugh] We audition hundreds of people and we take twenty-four.

PC: It was by

accident forty years ago. I was here to sing the American

premiere of the War Requiem

with the BSO. We did the first performances at Tanglewood, then

three or four in Boston and then in New York. It was a longer

rehearsal period than usual for things at the BSO in the summer.

Erich Leinsdorf was the conductor. [See my Interviews with Erich

Leinsdorf.] The opera program, which had been here for a very

long time, had been discontinued, and there were lots of rumors

around. I have no idea why, really, but there was no opera

program. They had a group of singers that had been brought up for

the summer, and I think it was Harry Kraut came to me and said,

“Phyllis, we have all these really unhappy singers. Can you think

of something to do?” I said, “I don’t really think so, but I

suppose we can sit around and talk about singing.” That’s how the

classes began, and they’ve been going on ever since. [Both

laugh] We audition hundreds of people and we take twenty-four.

PC: Oh well, that

was easy. All the vocal arts interested me, and I’d had a nice

background. Singing really caught on that junior year in

college. My dean had told me, no, I could not take lessons

because I would be carrying an extra subject and that was too

much. If I took practical music I would have to take a

theoretical subject. I explained that I’d had theory and I’d had

harmony and all of that, but it didn’t cut any ice. Years later

when I was a dean I remembered this very well. So I went to the

lady whose picture is on the piano, a Russian lady, Olga Averino, who

was teaching at Wellesley for a few years. [Note: Averino’s

mother was the God-daughter of Tchaikovsky, and Olga was the

God-daughter of Tchaikovsky’s brother, Modest.] I

explained all of this and I said, “So, I thought maybe I’d take singing

lessons in Boston.” She said, “Have you something to sing?” and I

said, “No, ma’am.” “Can you read?” “Yes,” so she arranged

it that I could take lessons. [Laughs] I found that in song

literature there was everything in the world that I loved. I had

danced for years; I did theater; I love poetry, and it was all in there

along with the music. So I adjusted my life to keep studying

more, and one thing led to another. But the business about

stopping is very interesting. As I said, things which had always

been easy began to be not so easy. I would listen to friends of

mine who were around my age and I’d hear in them things that were

happening to me. It was a hard decision, but one day I simply

called Columbia Artists and said, “I’m not going to sing anymore.”

PC: Oh well, that

was easy. All the vocal arts interested me, and I’d had a nice

background. Singing really caught on that junior year in

college. My dean had told me, no, I could not take lessons

because I would be carrying an extra subject and that was too

much. If I took practical music I would have to take a

theoretical subject. I explained that I’d had theory and I’d had

harmony and all of that, but it didn’t cut any ice. Years later

when I was a dean I remembered this very well. So I went to the

lady whose picture is on the piano, a Russian lady, Olga Averino, who

was teaching at Wellesley for a few years. [Note: Averino’s

mother was the God-daughter of Tchaikovsky, and Olga was the

God-daughter of Tchaikovsky’s brother, Modest.] I

explained all of this and I said, “So, I thought maybe I’d take singing

lessons in Boston.” She said, “Have you something to sing?” and I

said, “No, ma’am.” “Can you read?” “Yes,” so she arranged

it that I could take lessons. [Laughs] I found that in song

literature there was everything in the world that I loved. I had

danced for years; I did theater; I love poetry, and it was all in there

along with the music. So I adjusted my life to keep studying

more, and one thing led to another. But the business about

stopping is very interesting. As I said, things which had always

been easy began to be not so easy. I would listen to friends of

mine who were around my age and I’d hear in them things that were

happening to me. It was a hard decision, but one day I simply

called Columbia Artists and said, “I’m not going to sing anymore.” BD: Let me turn the

question around. Was there any role that was perhaps a little too

close to the real you?

BD: Let me turn the

question around. Was there any role that was perhaps a little too

close to the real you? PC: Oh, it’s

wonderful! I think that’s almost more fun than anything.

There’s nobody saying, “Well, you know, madam so-and-so always sings it

this way.” With all of Carlisle’s things that I did first

— Wuthering Heights,

Flower and Hawk, The Passion of Jonathan Wade

— it was really wonderful fun. I remember with The Passion of Jonathan Wade,

Celia, the heroine, is such a lovely, full-blown, normal lady, and so

much of it was written so high. I said, “You know, it doesn’t

seem to me to be the right voice for her.” It was fun.

Carlisle listened and listened and he said, “Isn’t that funny? It

didn’t sound that way in my head.” He brought some of that down,

but that’s about the only time. When I’ve worked with other

composers, it’s also been just wonderful. I have had this long

relationship with Ned Rorem. [See my Interview with Ned Rorem,

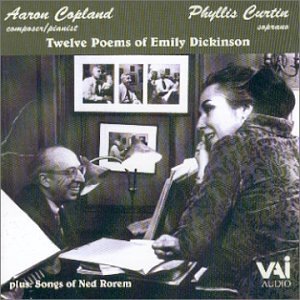

which includes another (much earlier) photo of Curtin.] Copland

and I did his Dickinson Songs

many times together, and that was always fun. It’s

special, very Copland-esque when he plays it.

PC: Oh, it’s

wonderful! I think that’s almost more fun than anything.

There’s nobody saying, “Well, you know, madam so-and-so always sings it

this way.” With all of Carlisle’s things that I did first

— Wuthering Heights,

Flower and Hawk, The Passion of Jonathan Wade

— it was really wonderful fun. I remember with The Passion of Jonathan Wade,

Celia, the heroine, is such a lovely, full-blown, normal lady, and so

much of it was written so high. I said, “You know, it doesn’t

seem to me to be the right voice for her.” It was fun.

Carlisle listened and listened and he said, “Isn’t that funny? It

didn’t sound that way in my head.” He brought some of that down,

but that’s about the only time. When I’ve worked with other

composers, it’s also been just wonderful. I have had this long

relationship with Ned Rorem. [See my Interview with Ned Rorem,

which includes another (much earlier) photo of Curtin.] Copland

and I did his Dickinson Songs

many times together, and that was always fun. It’s

special, very Copland-esque when he plays it. PC: Interesting

question. Huh... what do I start with? I was going to say I

start with text, but that’s not really true at all. I don’t

know. I look at the music, I look at the text, I look at vocal

line. I try to find out how what’s going on in the score is

related to what’s being said, and why is that, and if it’s convincing

to me or even challenging. One of the funniest pieces I ever did

was at Yale. It was calligraphy. It didn’t have any notes

at all. The composer was sitting in front of some discs that were

playing, and there was my part. I don’t even remember anything

about the text anymore, but he was very interesting as a

calligrapher. Some of it was very small, and some of it looked

like a big L. I simply made up sounds to go with whatever that

was. It was fascinating.

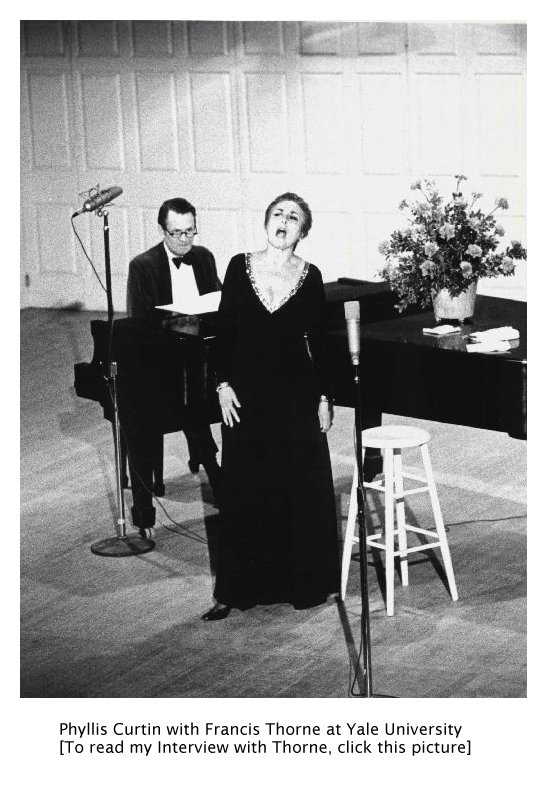

PC: Interesting

question. Huh... what do I start with? I was going to say I

start with text, but that’s not really true at all. I don’t

know. I look at the music, I look at the text, I look at vocal

line. I try to find out how what’s going on in the score is

related to what’s being said, and why is that, and if it’s convincing

to me or even challenging. One of the funniest pieces I ever did

was at Yale. It was calligraphy. It didn’t have any notes

at all. The composer was sitting in front of some discs that were

playing, and there was my part. I don’t even remember anything

about the text anymore, but he was very interesting as a

calligrapher. Some of it was very small, and some of it looked

like a big L. I simply made up sounds to go with whatever that

was. It was fascinating. PC: Of the few

recordings that are around of mine, most of them are from tapes that

were made live. There is Luonnotar

with the New York Philharmonic and Bernstein, and also some Sibelius

songs which were recorded with the orchestra and there are microphones

all over the place. I never thought of it at all, so no, I didn’t

change. I did very little studio work, almost none. I

remember for the French stuff, Chanson

d’Eve and six poems of Paul Verlaine set by Fauré then

Debussy back and forth. I did that at a second town hall recital

because I’d had a nice success at my first one. Then by carefully

reading the newspaper, I noticed that very often at a second recital,

if your first one had been reviewed very well, people were out to pick

on you. So I thought I’d try to make a program that will be so

interesting to the critic that he’ll forget about me.

[Laughs] So the second half was the six poems of Paul Verlaine,

and everybody argued about who they liked best, Fauré or

Debussy. I got by nicely. [Both laugh] But I recorded

that on the stage in the Boston University Concert Hall about a hundred

years ago, and I don’t even remember about microphone. I remember

recording the Brahms Requiem

with the Philadelphia Orchestra and the Mormon Tabernacle Choir out

there. I would listen to the playback I sounded a million miles

away. McClure was the chief engineer there for a long time and he

said, “Phyllis, you’ll get used to it.” For the recording Der Wein of Alban Berg, and Wozzeck excerpts with the BSO, they

put me on the stage but the orchestra was in the house. Again

there were microphones in all kinds of places. When we listened

to playback after one go-through of the Wozzeck, it was fascinating because

it was really marvelous until we got to that last pianissimo B

Flat. Suddenly came out forte, and Dick Mohr of RCA said, “Oh,

Phyllis, I’m so sorry. I looked away from the score and I just

turned it up when I heard that. But I’ll just turn it

down.” I said, “But I want my piano, not yours.” [Both

laugh] Perhaps if I had been recorded a lot I would have been OK

with that, but I never let it be the engineer’s problem instead of mine.

PC: Of the few

recordings that are around of mine, most of them are from tapes that

were made live. There is Luonnotar

with the New York Philharmonic and Bernstein, and also some Sibelius

songs which were recorded with the orchestra and there are microphones

all over the place. I never thought of it at all, so no, I didn’t

change. I did very little studio work, almost none. I

remember for the French stuff, Chanson

d’Eve and six poems of Paul Verlaine set by Fauré then

Debussy back and forth. I did that at a second town hall recital

because I’d had a nice success at my first one. Then by carefully

reading the newspaper, I noticed that very often at a second recital,

if your first one had been reviewed very well, people were out to pick

on you. So I thought I’d try to make a program that will be so

interesting to the critic that he’ll forget about me.

[Laughs] So the second half was the six poems of Paul Verlaine,

and everybody argued about who they liked best, Fauré or

Debussy. I got by nicely. [Both laugh] But I recorded

that on the stage in the Boston University Concert Hall about a hundred

years ago, and I don’t even remember about microphone. I remember

recording the Brahms Requiem

with the Philadelphia Orchestra and the Mormon Tabernacle Choir out

there. I would listen to the playback I sounded a million miles

away. McClure was the chief engineer there for a long time and he

said, “Phyllis, you’ll get used to it.” For the recording Der Wein of Alban Berg, and Wozzeck excerpts with the BSO, they

put me on the stage but the orchestra was in the house. Again

there were microphones in all kinds of places. When we listened

to playback after one go-through of the Wozzeck, it was fascinating because

it was really marvelous until we got to that last pianissimo B

Flat. Suddenly came out forte, and Dick Mohr of RCA said, “Oh,

Phyllis, I’m so sorry. I looked away from the score and I just

turned it up when I heard that. But I’ll just turn it

down.” I said, “But I want my piano, not yours.” [Both

laugh] Perhaps if I had been recorded a lot I would have been OK

with that, but I never let it be the engineer’s problem instead of mine. BD: I hope you were

pleased with some...

BD: I hope you were

pleased with some...

This interview was recorded in her home in Great Barrington, MA

on August 24, 2003. Portions

were used (with recordings) on WNUR in 2004 and 2012. This

transcription was made and posted on this

website in 2013.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website, click here.

Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM, as well as on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio.

You are invited to visit his website for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.