Pianist Maria João

Pires

A Conversation with Bruce Duffie

Born on 23 July 1944 in Lisbon, Maria João

Pires gave her first public performance at the age of 4 and began her

studies of music and piano with Campos Coelho and Francine Benoît,

continuing later in Germany, with Rosl Schmid and Karl Engel. In addition

to her concerts, she has made recordings for Erato for fifteen years and

Deutsche Grammophon for twenty years. Since the 1970s, she has devoted

herself to reflecting on the influence of art on life, community and education,

trying to discover new ways of establishing this way of thinking in society.

She has searched for new ways which, respecting the development of individuals

and of cultures, encourage the sharing of ideas. In 1999, she created

the Centre for the Study of the Arts of Belgais in Portugal. She broadened

the reach of this philosophy to Salamanca and Bahia in Brazil. In 2012,

in Belgium, she initiated two complementary projects; the Equinox project

which creates and develops choirs for children from disadvantaged backgrounds,

and the Partitura project, the aim of which is to create an altruistic

dynamic between artists of different generations by proposing an alternative

in a world too often focused on competitiveness.

-- Askanas Holt (agent)

|

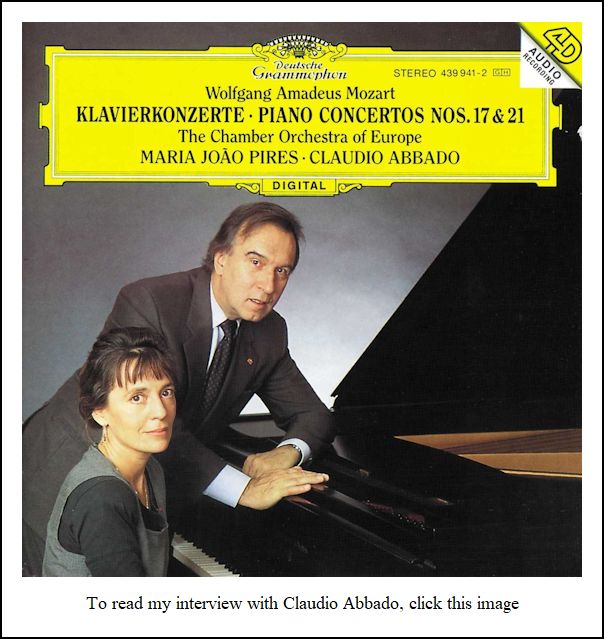

In March of 1991, Maria João Pires was in Chicago for four

performances of the Chopin Piano Concerto No. 1 with the Chicago

Symphony conducted by Christopher

Keene. Also on the program was the Symphony for Classical

Orchestra by Harold

Shapero, a neo-romantic work. [Names which are links refer to

my interviews elsewhere on my website.]

While she was here, Ms. Pires graciously took time to speak with me.

Portions of the interview were aired a couple of times on WNIB,

Classical 97, and now the entire conversation has been transcribed and

is presented here.

Bruce Duffie: You’re here in Chicago playing Chopin,

but you’ve made a special mark with Mozart. Tell me the secret of

performing Mozart.

Maria João Pires: I don’t think I have any

secret. I started playing Mozart very soon when I was a little girl.

My first concerto with orchestra was a Mozart concerto when I was eight

years old. I hadn’t many reasons to go on playing Mozart. My

repertoire for solo pieces was probably quite big, but for orchestra it’s

quite limited because I have small hands and not much weight. [Laughs]

So I played all the Mozart concertos...

BD: You played all twenty-seven?

BD: You played all twenty-seven?

MJP: No, about twenty, and I played all the Mozart

sonatas that I recorded. That’s the composer I play a lot, but I

can’t say that I prefer to play Mozart than other things. I can’t say

that at all, but that’s the music I studied very much, and in quite a deep

way, so I had an approach that is very special.

BD: Do you get a special joy when you play Mozart?

MJP: Not more than other composers, probably because

of those very stupid reasons with my hands. I had probably a stronger

approach to the music since I have studied more and know, perhaps, more

about it. We never know much, but I did quite good work on Mozart’s

music.

BD: Have you ever considered using a smaller

instrument, such as a harpsichord or a fortepiano, where the keys are

slightly less wide?

MJP: No, because I started to play the piano when

I was three years old, and when I play the harpsichord I feel it’s too

small. I’m used to the piano, and I prefer to choose my repertoire

and try to play pieces that are not impossible for me. I love pieces

by Brahms and Liszt very much, but these are the kinds of things I can’t

play.

BD: You do have quite a wide range, including

Chopin and Beethoven.

MJP: Yes, Chopin is not very hard for small

hands. As music, Chopin is so well-written for the piano. This

means that he was a man who knew the instrument so well and so deeply,

that if you have small hands or big hands you can always manage.

Of course, there are some pieces — like perhaps

one or two Polonaises, or two or three Études

— that are a little hard for me to play, but normally Chopin

is not a big problem.

BD: With this wide range of possibilities, how

do you decide which pieces you will concentrate on?

MJP: I have lots of concerts — too

many, more than I wish I would have — and I have

to take a little time each year for making new programs, to practice, to

study new music. Normally I learn two or three new pieces each year,

or one concerto. Sometimes I’m looking to learn something for two

or three years, and I have no time to do it. Then suddenly I have one

month free and I can do it. But it’s difficult to say how I choose.

I think it’s very natural. You feel you’re ready to do something,

or you feel you are not ready to do something. There’s a time for

everything, and sometimes I love a piece very much and wish I could play

it, but I don’t feel ready to do it. I take the score and read it,

and then I just leave it for some five years more. Then, suddenly something

happens, and you feel like it’s going to be possible.

BD: Do you then have a greater understanding

of it?

MJP: Yes, and it also depends on your age.

There are things you play when you’re twenty, and you feel you can’t understand

them. You play them, but you think one day it’s going to be different,

and it is. I don’t like to force myself. I also don’t like to

force myself to choose repertoire that I don’t love very much. I

don’t do that very much. It’s a need for me that I have to have a

big passion for the piece that I want to play. I can’t play a piece

because somebody says I should play it, or because it’s fashionable to play

that kind of thing. That’s something I can never do. I always

have to feel a big and a very strong relationship to the piece, and it must

be the right moment to do it. This is not a secret, but something probably

everybody does. It is something that you can’t explain. It must

just come naturally.

BD: I assume, though, that there are many, many

pieces you are looking forward to tackling?

MJP: Of course, yes.

BD: So one by one, little by little, you’ll work

on them?

MJP: Of course. The piano has such a big

repertoire that you never have the time in your life to do everything

you would like to do. I’m just trying. [Laughs]

* * *

* *

BD: How do you divide your career between concertos

and solo recitals?

MJP: I can say normally it’s about half and half.

There are some years when I play more with orchestra, but then comes two

or three months where I do many recitals. So, it depends, but it’s

about half and half. It’s not me that decides that kind of things.

Normally it’s the agent that makes the schedule, and sees what I can do

here and there. I don’t choose these. I just agree or not to

play at different places.

BD: Is it exciting to come to a new city to meet

a new orchestra?

MJP: Yes, of course. I enjoy very much being

in Chicago. It is the first time. It was planned that I would

come some four years ago to do a recital, but I canceled because I had flu.

I was not doing well, so I went home and canceled this recital.

So this is my first time in Chicago, and I felt people were very kind.

I was somewhat surprised about Chicago, about how it looks.

BD: It was different than you expected?

MJP: Yes, very different. Europeans have

an idea about Chicago that it is a crazy city, very much polluted in all

senses, and very much noisy and very much dirty, and so on. I felt

exactly the opposite. I felt it was quite open and nice, and beautiful,

with the beautiful lake, and very nice people. It is very quiet

and nice. I enjoy it more than New York.

BD: Hurray for us! [Both laugh] Do

you find that the audiences are very different from city to city and country

to country?

MJP: In Europe the differences are enormous from

country to country, even in the same country from one city to the other.

In the States it’s very much uniform. you don’t feel the differences

so much.

BD: What are the big differences in

Europe then from city to city?

MJP: There are cities where people love music and

know music because of their tradition, like Germany and other Northern

countries like Switzerland. People learn music at school, so everybody

knows something, and many love music. But they are quite cold about

showing their love for it. The audience is quite formal. You

don’t feel so much warmth. Then there are countries were people are

not used to going to concerts so much, like in the South. Sometimes

you think they don’t have the same tradition, but the audience is very

warm, and the contact is more easy.

BD: There is more enthusiasm?

BD: There is more enthusiasm?

MJP: More enthusiasm, much more. But this

does not mean that it is better or worse. It’s just different.

In the United States, I felt no difference between Chicago and Dallas, or

between New York and Los Angeles.

BD: There is the same kind of warmth?

MJP: Yes, the same kind of communication.

BD: Are we warmer or colder than Europe?

MJP: It’s probably a little colder here... not

really colder, it’s a little more distant. It’s difficult to explain.

BD: Is it, perhaps, that we don’t have the lengthy

tradition that they have in Europe?

MJP: Yes, but in Europe you have different kinds

of cultures. There are some countries where you have no tradition,

or very little, but people react. They have a reaction that is very

spontaneous.

BD: Do you feel that the recording industry is partly

to blame for this, because a recording will be heard and appreciated everywhere?

Does this help to make our reactions all the same?

MJP: I don’t know. It’s the American way

of life, which is very different from ours. The way how people behave

is very different, and probably there are differences between cities in

America, but I don’t feel them so much because I don’t know them.

BD: You spend most of your time in Europe?

MJP: Oh, yes. I just came here four or

five times to play, and I’ve never lived here.

BD: Are you still living in Portugal?

MJP: No, we live in France, in the country, but

quite near Paris.

BD: Are you assimilating Parisian taste and style?

MJP: Not at all! I’m very far from that!

[Laughs] I have many good friends in Paris, and in France, and I

have probably more relationship to France and to French people than to

Germany and the north countries because I’m from Portugal. But I

live near Paris. I would not like to live in Paris, and I would not

like to live in any big city. I’m very much somebody that needs the

nature and needs to be outside.

BD: You want to be more rural?

MJP: Yes, yes, very much. I never had the

chance to live a long time on a farm. I have a farm which we bought

some years ago in Portugal. We keep this farm going, and we built

a house there. I’m trying to make some things very nice so that we

can go there and practice for two or three months, but it’s still not ready.

BD: Do you do anything for Portuguese composers?

Are there any noteworthy composers?

MJP: No, not really fantastic Portuguese composers.

Portugal has a very special and big tradition for literature, so books

are something that are very important in Portugal, as well as its writers

and poets. But music is something that was never the strongest talent

from Portuguese people. It’s much more in Spain than in Portugal.

We have some composers that are not much different from others from their

time, and when I was a student I played some modern and some old Portuguese

composers. I’m not still not playing them all the times when people

ask me to do it, but it’s nothing that is really interesting.

BD: I just wondered if maybe you’d put one or

two little pieces on a recital program.

MJP: We have some very new composers who are

very good. Contemporary music is something that I appreciate, but

I don’t play myself. I wanted to try many times, and I played modern

music from our century, but the very contemporary music I never studied.

One reason is that I never felt the patience to do it. I

never had the feeling that I have to do it, and that is something I need

very much. So, I’m waiting for that. [Laughs] The other

reason is that there are so many pieces from other times that I wanted

to play, and I have such a short time each year to practice, that normally

I give the preference to other things. If I would have three or

four or five free months a year, I would probably try to play some new

things.

BD: If someone were to come to you and say, “I

would like to write a piece for you to play,”

what advice would you have for the composer?

MJP: I would say first to take care of my hands,

which are not big. Don’t write very big things.

BD: No tenths!

MJP: Yes! [Both laugh]

* * *

* *

BD: This week in Chicago you’re playing the Chopin

concerto four times. How do you keep it fresh for the third and fourth

performance?

MJP: If I had to play it twenty times, I would

probably have the problem once. But four times is not too much, because

I love this piece very much, and you’re never happy with what you do.

Normally you do it and you’re very unhappy about it, and the second time

you think it’s going to be a little better there and there. You think

of this part and this thing you couldn’t do, and then the second time

it’s even worse than the first! [Laughs] Then you try again.

This is one reason, and the other reason is that each time somebody plays

the piece, it’s like always the first time. It’s like something that

you don’t have a memory about doing. The moment is so important.

You have to be so much inside the piece, with so much concentration about

giving from yourself everything you can. That’s not something you

get used to. You don’t get used to playing, at least I don’t.

It happens that I do many, many concerts during the year, and I never get

used to the stage. I never say, “Today is the

second time, or the third time, or the hundredth time.”

BD: Nothing is routine?

MJP: No.

BD: Do you feel each time you’re

out on the concert stage that you’re creating something new?

MJP: Yes, I have to. It’s not an effort,

but if it wouldn’t be so, I think I’d have to stop playing. I could

never make it a routine doing something like that.

BD: Do you play in the same recording studio that

you do in the concert hall?

MJP: Normally, yes, I think so. You know,

I’m not sure. Probably there’s one difference... when I’m doing

a record, I’m less nervous because I don’t have the audience, which makes

me feel a little more relaxed. That’s why I like so much to make records.

It doesn’t mean that I’m the kind of person who is scared to play onstage.

I know other pianists and other musicians who are more nervous than

I am to play on stage, but I am, like everybody, a little nervous, a little

scared about playing badly, about making people disappointed about what

you’re doing. People come expecting something, and they have to go

home even if they’re disappointed. That’s not a good feeling.

So, you are always a little scared about that, but when I make records, that’s

another feeling. You are relaxed, but you have the feeling at the same

time that you play for the people, for the audience. That’s a very

nice feeling. The difference should be that you in playing in a different

way. If you are really relaxed or if you are a little scared, but

I prefer to be relaxed.

BD: I assume that you make long takes?

BD: I assume that you make long takes?

MJP: Always. I have to make cuttings, but

I always do the whole movement again. It’s important.

BD: Are you pleased with the recordings

that you’ve made over the years?

MJP: I have to tell you I’m very special about that.

I can’t listen to my records. It would be irresponsible if I wouldn’t

listen one time. I have to listen that one time and say

it is okay. I must approve them. But this is a

terrible moment for me because normally I don’t listen really well. Maybe

it would be better if someday I don’t listen and just say that I approve!

[Much laughter] I listen, but in a way that I’m so scared about what

I did. You just finish doing something, and you think you could do

it better. On the other hand, nobody’s perfect. But I think

that other people can play much better than I can. But if I start

to have so many questions about what I need, and how I could do it, I wouldn’t

ever do it! [More laughter]

BD: You have to have enough courage just to play

your best?

MJP: Yes, that’s what I do. Normally I

close my eyes and do my best, and then it’s okay.

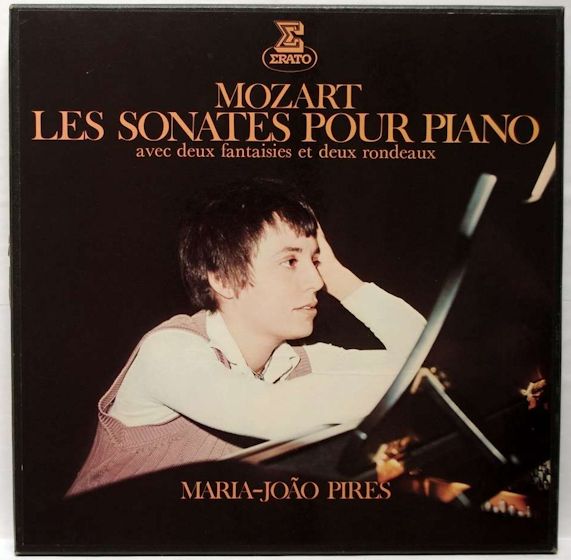

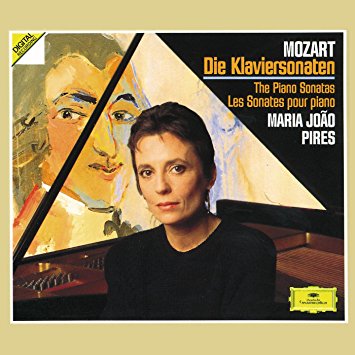

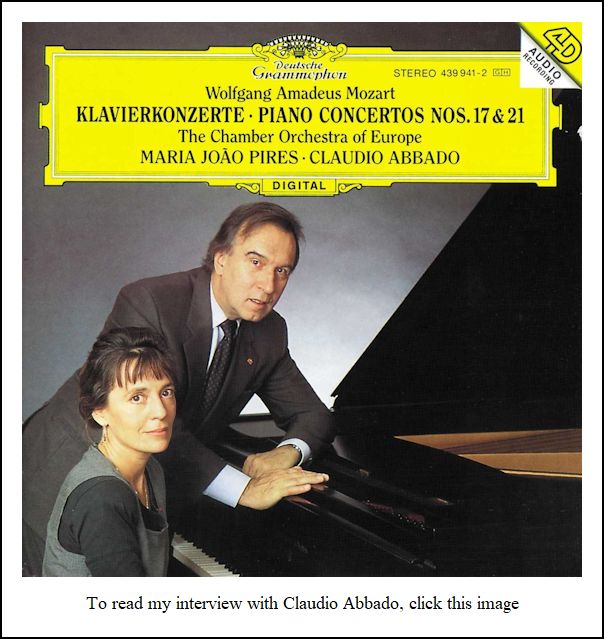

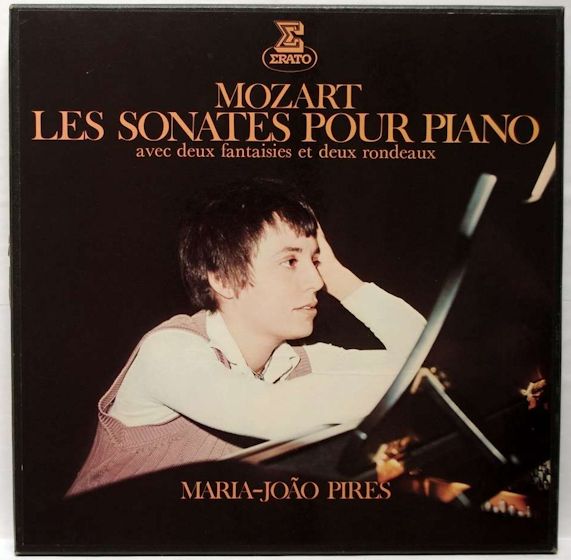

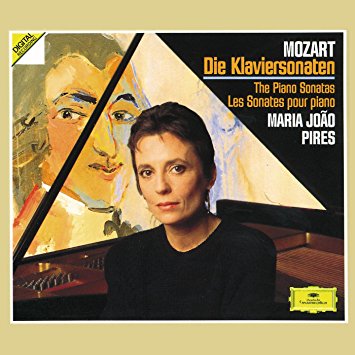

BD: You recorded the complete cycle of Mozart

sonatas many years ago [shown at left], and now you’re coming back

and recording it again [shown below right]. How will they

compare one to the other?

MJP: I did it; it’s finished. They’ll be

out in June. As to a comparison, you should tell me, not ask me!

[Both laugh] It’s up to you to say, or to make your judgment.

I think there is a big difference, as much as some human being can change

in life. The changes are probably small, but there are changes.

BD: I assume you don’t want to disown the earlier

set, or suppress it?

MJP: Oh, no! I don’t have any reason for that,

no. It’s probably interesting for other people to compare, but I’m

sure myself that it’s quite different. It’s twenty years ago. That’s

a long time.

BD: You’ve grown as an artist?

MJP: Yes. I’m getting older, and twenty years

more is quite a lot to think about, and to see my approach to the music

in another way. Your feelings change, your way to read behind the

score, to understand the analysis of the music is different, and just

the approach is very different. It’s changed a lot.

BD: Let me ask the big philosophical question.

What is the purpose of music?

MJP: Why music exists?

BD: Yes.

MJP: Music is probably the art that gives more of

an answer from the universe. This is my feeling from the whole thing.

The balance, the mathematics, the whole thing from the universe is

very, very much a secret. It’s also something you don’t need any

language any time. It’s not really dependent, like other arts are dependent

on time of style. Of course, it exists in the time, in the style,

in all these things, but it’s another idea which is way behind that music

which is something essential, something that translates the universe for

me. All my life I was interested in astronomy and physics and stars,

so that’s probably the reason why I have this image.

BD: Is music natural or supernatural?

MJP: I think both. That’s really the connection

between the natural, the supernatural, the human and non-human, and the

material and the non-material. It’s all things, the best connection

between what is real and the opposite from reality, and between the logic

and the non-logic. The best connection in music shows that all these

things which can seem very opposite are probably not so opposite.

BD: Music brings them together?

BD: Music brings them together?

MJP: Yes, very much so!

BD: Will you be back in Chicago?

MJP: I think so, yes.

BD: For a recital or a concerto?

MJP: Probably, for the orchestra. They

asked me to come, so probably I’ll come again with orchestra. [She

would return in March of 1994 for the Mozart Concerto #9, conducted

by Riccardo Chailly.]

It doesn’t mean that I would not like to do a recital here...

BD: When you go from city to city, how long does

it take you to acclimate to the new piano?

MJP: Normally it’s not very difficult.

We’re so used to playing each day on a different piano, so we’re used

to doing it. Every pianist is used to that, though there are some

cities, of course, where you have really bad pianos. They are sometimes

new, but hard and not nice. Then you suffer a lot, but you’re used

to doing that. It belongs to life and to your problems and your

work, as everybody has.

BD: You just do it?

MJP: You just do it!

BD: Here you had two or three to choose from?

MJP: No, this time I have a Yamaha piano that

came from them.

BD: They sent it in specifically?

MJP: They sent it because we were going to make

a record, but that fell through when the scheduled conductor [André Previn, with

whom she had recorded the Concerto #2] became ill and canceled his appearance

here. [Pires would later record the work (again, for the second

time) with a different conductor.] I play many times on Yamaha

because they have very good instruments and very special technicians. The

Japanese are very good for that, and they also have fantastic assistants.

They sometimes put me where there are no good pianos, and they help

me a lot by sending a very good tuner. This can help.

BD: So you’re a Yamaha artist?

MJP: I have absolutely no contract with Yamaha.

I’m just trying to play as much as possible when there are good

pianos, because it helps me. They help me a lot, so it’s just an

agreement without any other commitments. [This has changed,

as shown in the recent photos below.]

BD: Thank you for coming to Chicago, and for

speaking with me today.

MJP: It was a big pleasure. Thank you.

© 1991 Bruce Duffie

This conversation was recorded in Chicago on March 25, 1991.

Portions were broadcast on WNIB in 1994 and 1999. This transcription

was made in 2018, and posted on this website at that time.

My thanks to British soprano Una Barry for her help in preparing

this website presentation.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed

and posted on this website, click here.

Award -

winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97

in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station

in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various

magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast

series on WNUR-FM.

You are invited to visit his website for more information about

his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus

a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your

attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who

was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You

may also send him E-Mail with comments,

questions and suggestions.

BD: You played all twenty-seven?

BD: You played all twenty-seven? BD: There is more enthusiasm?

BD: There is more enthusiasm? BD: I assume that you make long takes?

BD: I assume that you make long takes? BD: Music brings them together?

BD: Music brings them together?