|

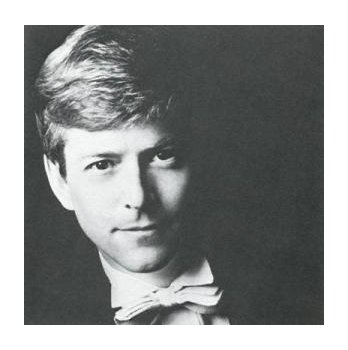

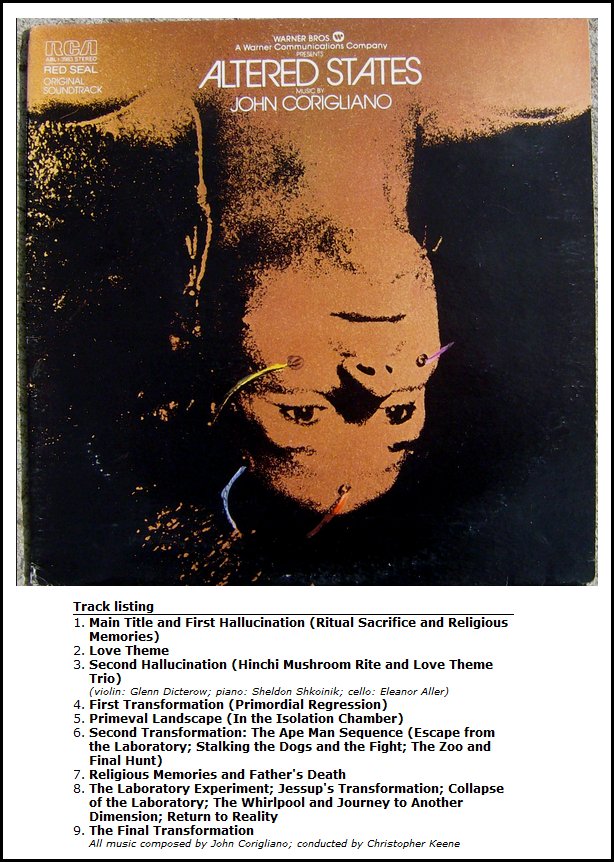

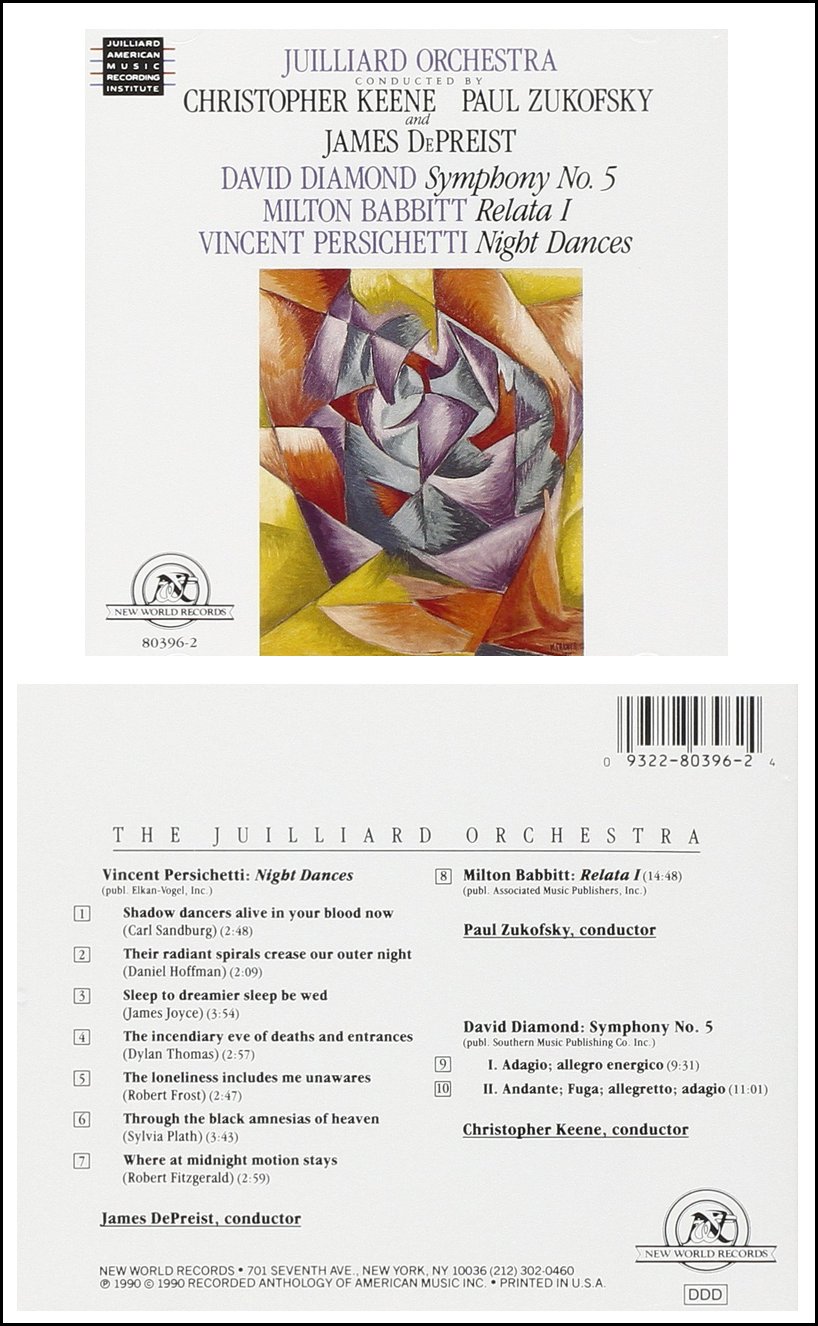

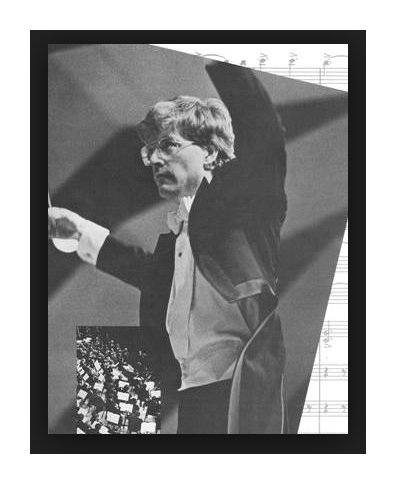

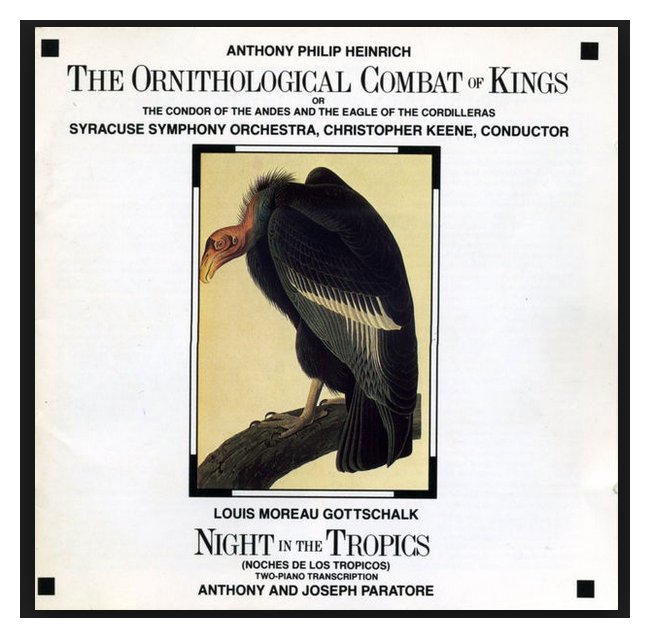

Christopher Keene (December 21, 1946 - October 8, 1995) was a highly-acclaimed American conductor. Born in Berkeley, California, Keene studied at the University of California, Berkeley. Associated with the Spoleto Festival from 1968 (and was Music Director there from 1972 to 1976), he was Co-Founder of the Spoleto Festival USA, where he was Music Director from 1977 to 1980. From 1969 to 1971 he was Music Director of Eliot Feld's American Ballet Company. In 1969, Keene joined the staff of the New York City Opera, where he debuted the following year with Ginastera's Don Rodrigo. He was to conduct a great array of operas at that theatre, including the world premiere of Menotti's The Most Important Man in 1971, as well as La Traviata, Le Nozze di Figaro, The Makropoulos Case, Susannah, Tosca, Beatrix Cenci, Faust, Die Zauberflöte, L'incoronazione di Poppea, Ariadne auf Naxos, Médée (in the Italian version), I Puritani (with Beverly Sills), Salome, A Village Romeo and Juliet, La fanciulla del West, Andrea Chénier, L'amour des trois oranges, The Turn of the Screw, Schönberg's Moses und Aron, and Zimmermann's Die Soldaten. Keene also conducted at the Metropolitan Opera during a single season, a double-bill of Cavalleria rusticana and Pagliacci in 1971. From 1974 to 1989, he was Music Director of the Artpark Festival in Buffalo, and from 1975 to 1985 held the same post at the Syracuse Symphony Orchestra. He was Founder of the Long Island Philharmonic in 1979, and directed it until 1990. In 1976, he led the world premiere of Carlisle Floyd's Bilby's Doll at the Houston Grand Opera. At the City Opera, Sills named him Music Director from 1982 to 1986, and he succeeded her as General Director in 1989, a position he held until his untimely death. Keene had undergone treatment for alcoholism at the Betty Ford Center, and died from lymphoma arising from AIDS, at New York Hospital, at the age of forty-eight. His last performance, at the City Opera, was of Hindemith's Mathis der Maler. He was seen over PBS conducting The Consul (1977) and Vanessa (1979) from Spoleto USA, and Frank Corsaro's City Opera productions of Madama Butterfly (1982) and Carmen (1984). Keene's discography includes the first recording of Philip Glass' Satyagraha (for CBS/Sony, 1984), and John Corigliano's score to Ken Russell's film Altered States (on RCA, 1980).  |

CK: Oh yes.

Not a

piece like Satyagraha,

although a case could be made that a piece like this would be at its

best if you got a fabulous orchestra and chorus together and sight-read

it. A funny cycle occurs in putting a piece together.

Generally you read a piece at a very high level of concentration.

Everybody has their feet on the ground and looks ahead and goes, and

you often achieve results in that first reading that it takes you a

long time to get back. The minute you start working on details,

things start to fall apart and get worse and worse for a while.

Then by dress-rehearsal and performance things get back together.

CK: Oh yes.

Not a

piece like Satyagraha,

although a case could be made that a piece like this would be at its

best if you got a fabulous orchestra and chorus together and sight-read

it. A funny cycle occurs in putting a piece together.

Generally you read a piece at a very high level of concentration.

Everybody has their feet on the ground and looks ahead and goes, and

you often achieve results in that first reading that it takes you a

long time to get back. The minute you start working on details,

things start to fall apart and get worse and worse for a while.

Then by dress-rehearsal and performance things get back together.

BD: Are you

optimistic

about the future of opera?

BD: Are you

optimistic

about the future of opera? CK: This year we do

Götterdämmerung and

in

June of 1989 we do the entire cycle. It has been a great

experience for me. An American conductor has almost no

opportunity to conduct Wagner in general and the Ring in particular. On the

rare occasions that it’s produced here, almost always a German

conductor is imported on the theory that only he would have enough

experience and background to be able to handle that immense structure;

and that’s a reasonable presumption. Amongst American conductors,

very few of us have actually had the opportunity to do the whole cycle

more than once, if that. So that’s been a tremendous

privilege. I’ve done Rheingold several times in the

theater, and I’ve done Walküre

before in concert. I’ve also done most of the big moments of Siegfried and Götterdämmerung in

concert. The cultural climate has switched around to where it’s

possible to look at Wagner again as an artist rather than as a kind of

political/sociological artifact. Immersing yourself in the man’s

life and music is really an overwhelming experience. Simply the

physical effort of conducting Siegfried,

which starts at 6 PM and goes to 11:15, is staggering – especially as

the last time I did it, the temperature was 92 degrees in

Lewisohn. That approximates the classical vision of

purgatory. The audacity of the man’s vision, and the

single-mindedness with which he carried it out, and the immense

tenacity

and complexity of his musical thinking is like climbing Mount Everest

when you deal with it. I can’t wait for the whole cycle to be

over so I can look forward to doing it again sometime. When you

climb Mount Everest for the first time, all you think about is getting

to the top. The next trip you begin to observe the beauty, so by

the tenth trip you begin to feel you know your way around. Just

surveying the territory is an enormous undertaking the first time

around for the conductor. You feel like you’re

standing at the bottom of this immense, immense peak which you hope you’ll

get to the top of.

CK: This year we do

Götterdämmerung and

in

June of 1989 we do the entire cycle. It has been a great

experience for me. An American conductor has almost no

opportunity to conduct Wagner in general and the Ring in particular. On the

rare occasions that it’s produced here, almost always a German

conductor is imported on the theory that only he would have enough

experience and background to be able to handle that immense structure;

and that’s a reasonable presumption. Amongst American conductors,

very few of us have actually had the opportunity to do the whole cycle

more than once, if that. So that’s been a tremendous

privilege. I’ve done Rheingold several times in the

theater, and I’ve done Walküre

before in concert. I’ve also done most of the big moments of Siegfried and Götterdämmerung in

concert. The cultural climate has switched around to where it’s

possible to look at Wagner again as an artist rather than as a kind of

political/sociological artifact. Immersing yourself in the man’s

life and music is really an overwhelming experience. Simply the

physical effort of conducting Siegfried,

which starts at 6 PM and goes to 11:15, is staggering – especially as

the last time I did it, the temperature was 92 degrees in

Lewisohn. That approximates the classical vision of

purgatory. The audacity of the man’s vision, and the

single-mindedness with which he carried it out, and the immense

tenacity

and complexity of his musical thinking is like climbing Mount Everest

when you deal with it. I can’t wait for the whole cycle to be

over so I can look forward to doing it again sometime. When you

climb Mount Everest for the first time, all you think about is getting

to the top. The next trip you begin to observe the beauty, so by

the tenth trip you begin to feel you know your way around. Just

surveying the territory is an enormous undertaking the first time

around for the conductor. You feel like you’re

standing at the bottom of this immense, immense peak which you hope you’ll

get to the top of.  BD: Is this, then,

fertile ground for you to make first-recordings?

BD: Is this, then,

fertile ground for you to make first-recordings?|

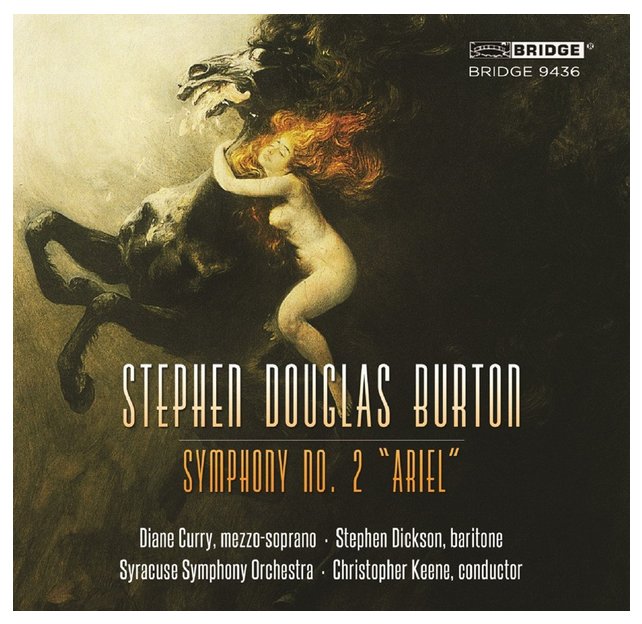

CHRISTOPHER KEENE: A Memorial Tribute by Marge Betley Christopher Keene, who died on Sunday, October 8, 1996, was best known as general director of the New York City Opera, a post he had held since 1989. His tenure there was fraught with financial, administrative, and personal challenges, including a musicians’ strike in his first season, a $2.9 million deficit in 1992, treatment for alcoholism two years ago, and, most painfully, a diagnosis of HIV and lymphoma. Keene, however, was a constant warrior, possessed of energy, vision, and integrity. His greatest legacy is his work as a champion of 20th-century music. Born in 1946 in Berkeley, California, Keene began producing and conducting opera as a student at the University of California, Berkeley. Even there, the proclivity for 20th-century music that would form the touchstone of his career was already evidenced by a series of productions that included Henze's Elegy for Young Lovers, von Einem's Trial and Britten's Rape of Lucretia. In 1966, Keene became assistant conductor of San Francisco Opera at the invitation of Kurt Herbert Adler; in 1967, he held the same position at San Diego Opera, where he worked on the American premiere of Henze's The Young Lord. The following year saw his European debut conducting Menotti's The Saint of Bleecker Street at the Spoleto Festival, where he eventually held the positions of music director and general director. As music director of the American Spoleto Festival, he conducted new productions of Weill's Mahagonny, Berg's Lulu, and Barber's Vanessa. Other guest engagements included the Metropolitan Opera, Lyric Opera of Chicago, the Royal Opera at Covent Garden, the Deutsche Oper of Berlin, and the Vienna Volksoper. Keene was a renaissance man of the music world, extending his talents far beyond the domain of opera. An active symphonic conductor, he was founder and director of the Long Island Philharmonic and led many of the major orchestras of North America and Europe, including the New York Philharmonic, the Chicago Symphony, the St. Paul Chamber Orchestra, the Berlin Radio Symphony, and the orchestras of Bonn, Basel, Nürnberg, and Düsseldorf. He was a steadfast presenter and recorder of the work of American composers, among them Philip Glass, Keith Jarrett, William Schuman, John Corigliano, and David Diamond. As music director of Eliot Feld's American Ballet Company, Keene composed music for Feld’s ballet The Consort. He wrote the libretto for Stephen Douglas Burton's The Duchess of Malfi and was writing the libretto for Charles Wuorinen's Celia the Slave at the time of his death. Among his other published works were translations of the libretti of Mozart's Don Giovanni and Henze's El Cimarron and Natasha Ungeheuer, as well as numerous articles for publications around the country. Ultimately it was as general director of the New York City Opera that Keene faced his greatest challenges, celebrated his most glorious victories, and survived what some would call his biggest failures. A frequent conductor there during Julius Rudel's and Beverly Sills’ regimes, he joined the staff as music director under Sills from 1982 to 1986, and assumed the general director's post in March, 1989. City Opera has often suffered in the shadow of its overwhelming Lincoln Center neighbor, the Met. It has been further challenged by a theater ill-suited to opera and unforgiving to the voices of the young singers that the company has tried to encourage. Part of City Opera's mandate has been to offer productions from the standard repertory at prices more affordable than its neighbor's, and Keene was actively engaged in the ongoing process of replacing some of those productions, which had gotten a bit shabby over the years. Clearly, however, Keene's greatest joy was commissioning new works and producing the seldom-seen. Some of these, like Schoenberg's Moses and Aaron and Zimmermann's The Soldiers, were undisputed triumphs. Others, like this year's productions of Hindemith's Mathis the Painter, Ezra Laderman's Marilyn, or Jay Reise's Rasputin, garnered criticism that ranged from middling to venomous. Nonetheless, Keene's loyalty to contemporary opera and composers was unwavering. “Lots of producers commission new works because they think it's the right thing to do,” says Opera News editor Patrick J. Smith, “but when the bad reviews come in ... Christopher was willing not only to commission a piece, but to stand behind it. He was very interested in new work and young composers, and not just as window-dressing.” Keene's stamp is all over this year's City Opera line-up, which includes Mathis — Keene conducted the opening night despite having only recently completed his radiation and chemotherapy treatments — and the American premieres of Mayuzumi's Kinkakuji and Meier's The Dreyfus Affair, along with Verdi's rarely-produced Attila. Unfortunately, his longtime dream of producing Janáček's Excursions of Mr. Broucek was postponed several years ago due to financial difficulties, and the work never made it back on the roster. According to Bernard Holland in the New York Times, “Keene had a way of staking his opera house on ventures that never had much chance of succeeding in the first place, but ones that had to be tried just the same ... These new operas freed us, for a moment at least, from the masterpiece syndrome, the rather addled modern expectation of genius every time out.” Keene was a big-picture thinker

who had faith in the cumulative achievement of generation after

generation of 20th-century composers. Just a few months before his

death, in an interview by James Oestreich for the New York Times, he

said: “I’ve always been a long-, long-, long-term planner. I had a plan

for life ... which went all the way until I was 90. And I was pretty

well on track. I don’t think in those terms any more.” Christopher

Keene was 48 years old when he died, truly in his prime as a champion

of new work. The world of contemporary music and opera can only imagine

what might have emerged from this visionary life cut short — and mourn. |

This interview was recorded in Chicago on October 17,

1987. Portions were used on WNIB

(along with musical examples) in 1989, 1991 and 1996. A

transcription was made in 1988 and published in Wagner News in September of that

year. It was re-edited and posted on this

website in October of 2008.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website, click here.

Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM, as well as on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio.

You are invited to visit his website for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.