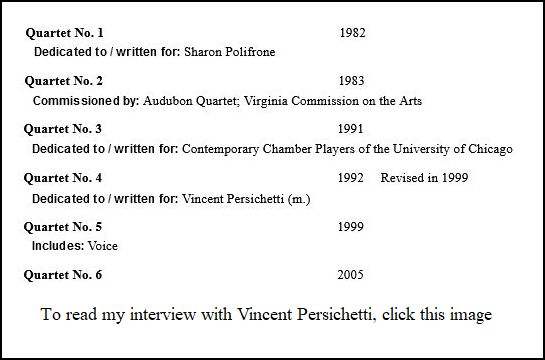

| Jon Polifrone, born in Durand, Michigan,

January 10, 1937, died March 11, 2006, at Loyola University Medical Center. Polifrone retired as professor of music from Virginia Tech in 2002, and then taught part-time at Judson College, Waubonsee Community College, and Wheaton College. He received a BM and MM from Michigan State University and a D.Mus from Florida State University. He was on the faculty of Jordan Conservatory (Indianapolis, 1963-1977), Indiana State University (full professor of music, 1963-1977), the University of Nebraska at Omaha (chairman, music department, JJB Isaacson professor, 1977-1980), and Virginia Tech (music department chairman, 1980-1983, full professor, 1980-2002). Polifrone was a fellow of St. Joseph's College (Indiana), a Rockefeller Grant recipient, and four of his compositions were nominated for a Pulitzer Prize. He received commissions for compositions from many musical groups, including the Indianapolis Symphony, the Audubon Quartet, and Ars Viva. He was a member of St. Mark's Episcopal Church, Geneva. He is survived by his wife, Sharon, and daughter, Alisa. |

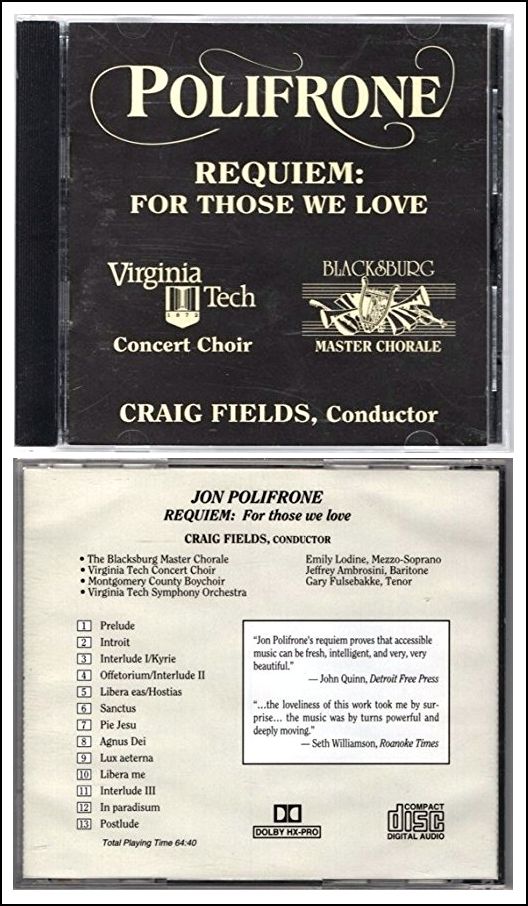

Polifrone: No. I’ve never done that, but the piece sometimes

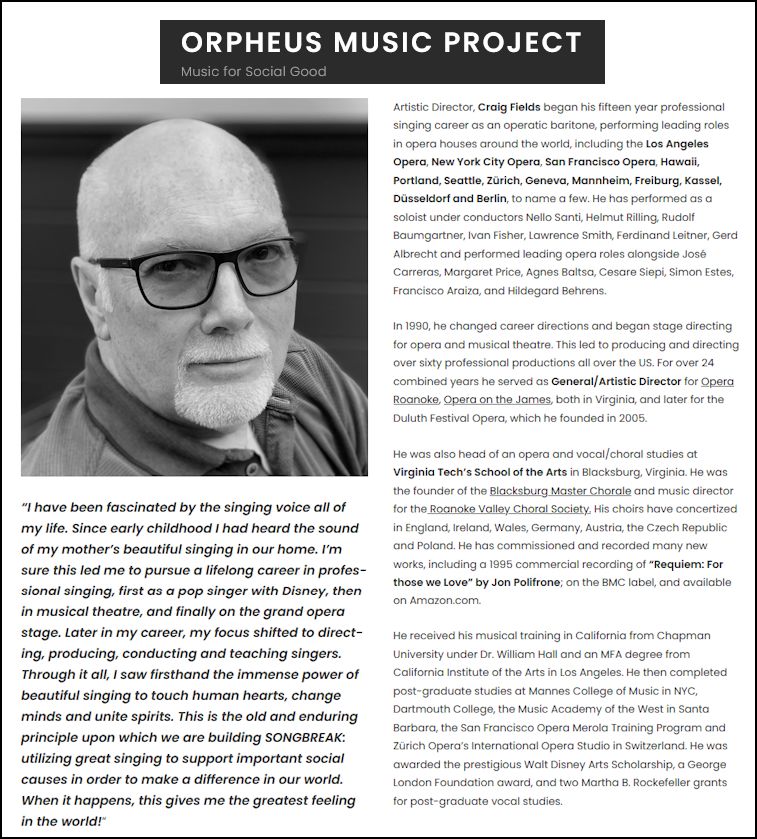

forces you to. When Craig Fields, director of the Blacksburg Chorale,

started working on the Requiem, he said, “Our group is not going

to be big enough. I’m to require at least sixty-five voices because

I need more power here.” So, we added the concert choir of Virginia

Tech, which is another sixty-five or seventy voices, and it made it really

very nice.

Polifrone: No. I’ve never done that, but the piece sometimes

forces you to. When Craig Fields, director of the Blacksburg Chorale,

started working on the Requiem, he said, “Our group is not going

to be big enough. I’m to require at least sixty-five voices because

I need more power here.” So, we added the concert choir of Virginia

Tech, which is another sixty-five or seventy voices, and it made it really

very nice.

© 1987 Bruce Duffie

This conversation was recorded in Chicago in March of 1994. Portions were broadcast on WNIB two months later, and again in 1997 and 1999. This transcription was made in 2022, and posted on this website at that time.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website, click here. To read my thoughts on editing these interviews for print, as well as a few other interesting observations, click here.

Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM, as well as on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio.

You are invited to visit his website for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.