|

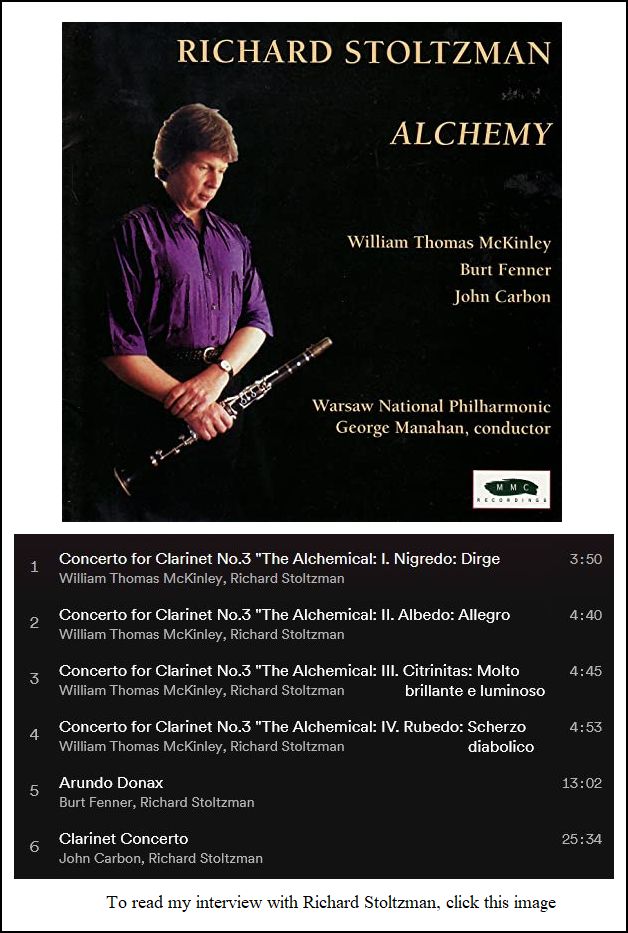

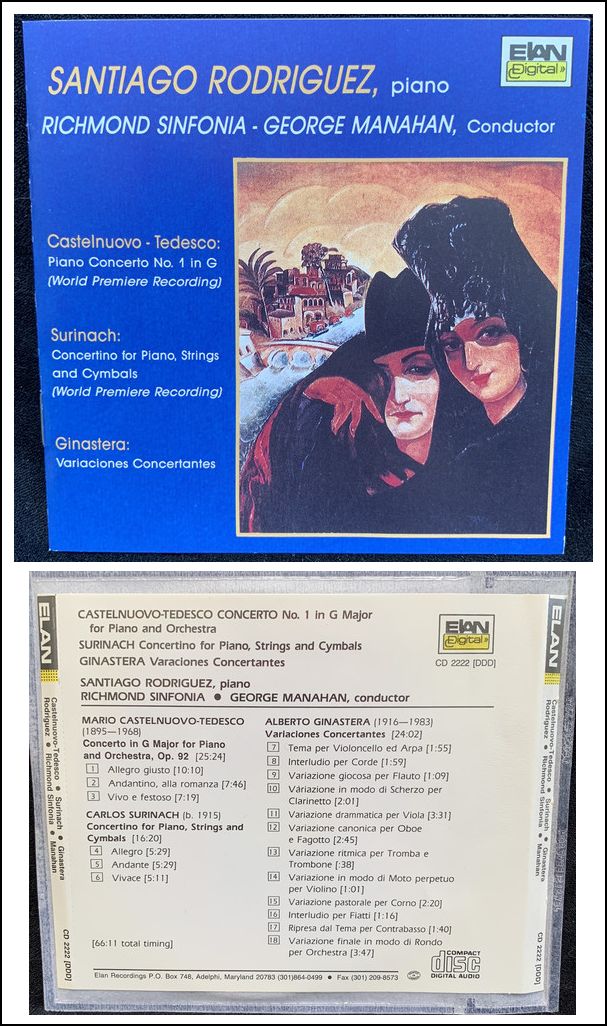

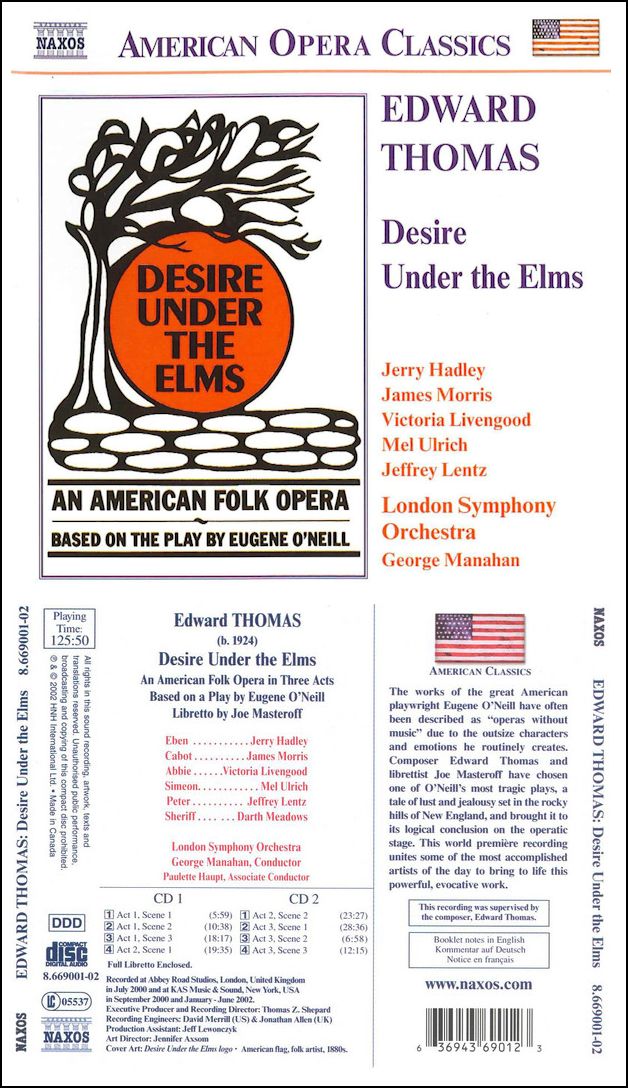

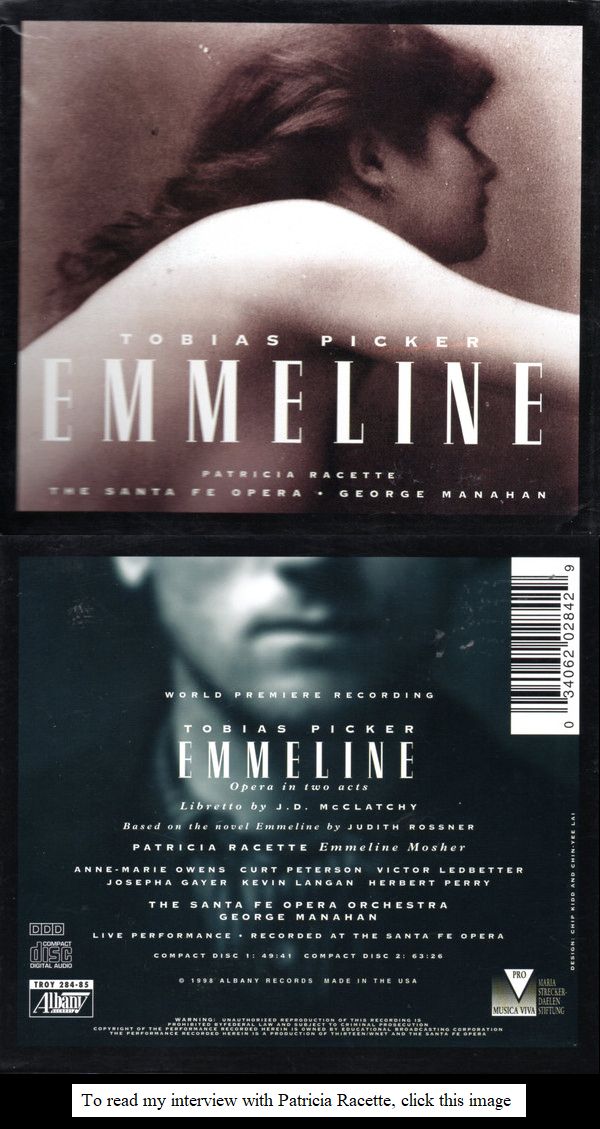

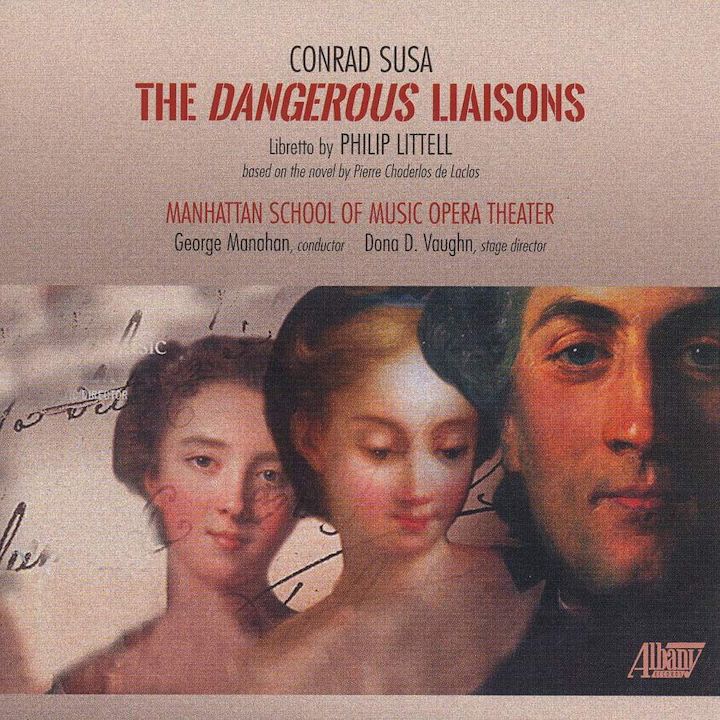

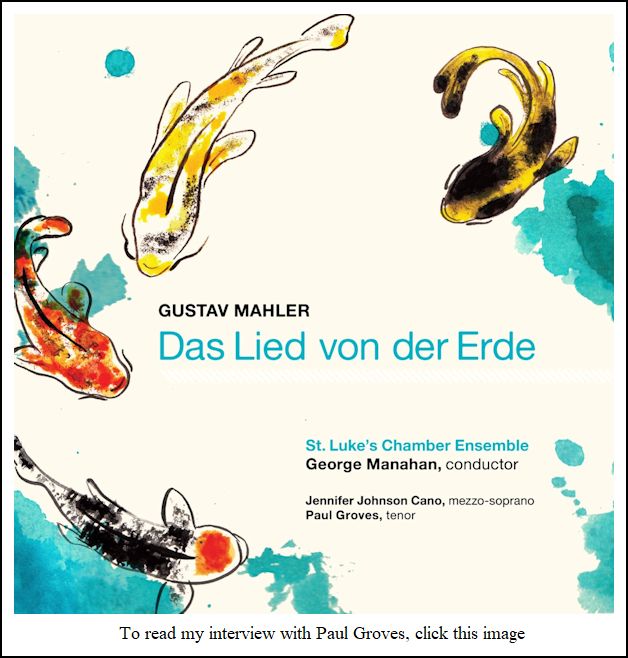

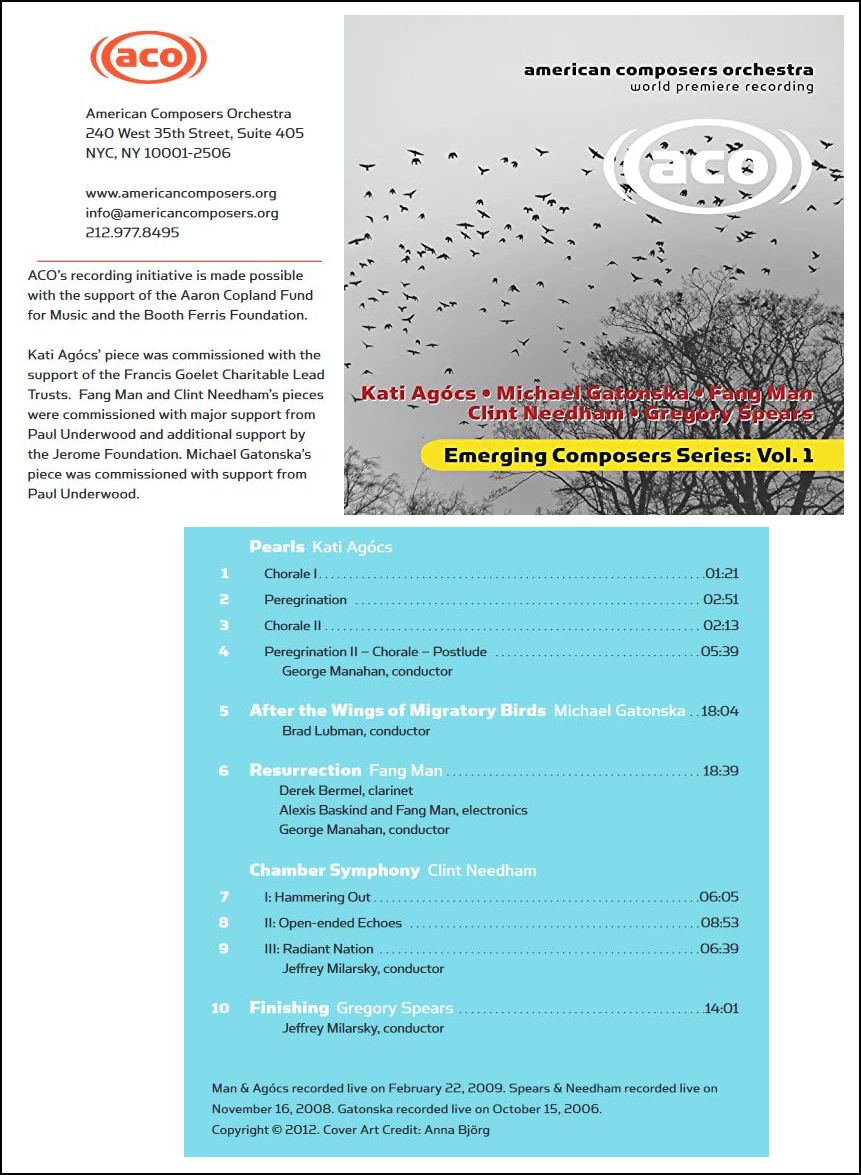

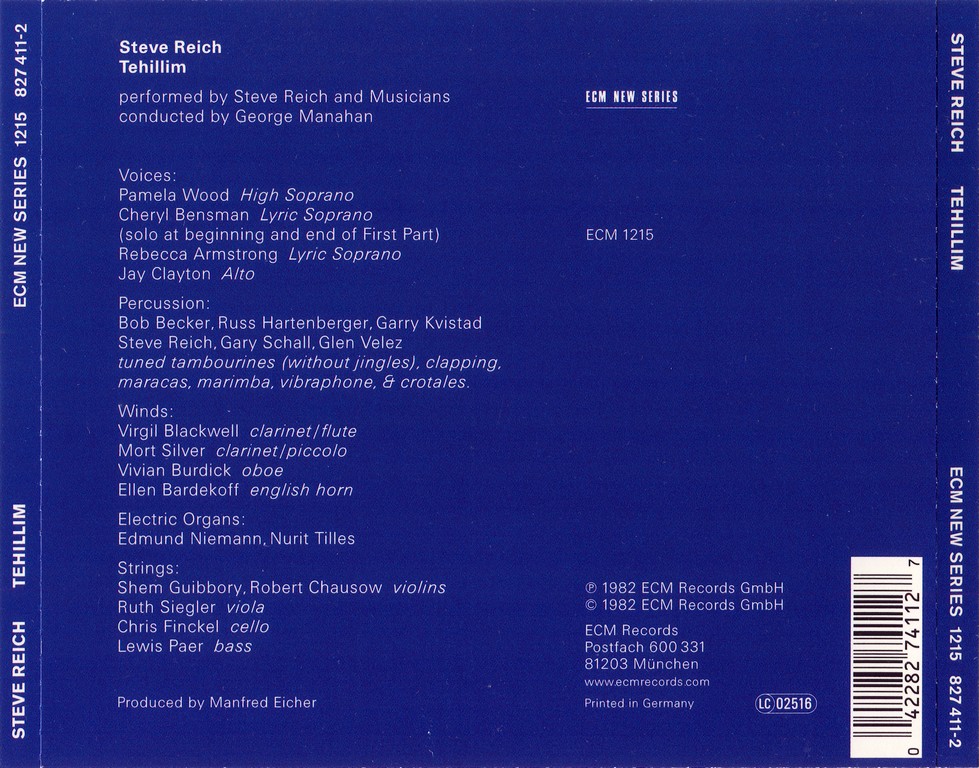

George Manahan is Director of Orchestral Activities at the Manhattan School of Music, as well as Music Director of the American Composers Orchestra and the Portland Opera. He served as Music Director of the New York City Opera for fourteen seasons and was hailed for his leadership of the orchestra. He was also Music Director of the Richmond Symphony (VA) for twelve seasons. Recipient of Columbia University’s Ditson Conductor’s Award, Mr. Manahan was also honored by the American Society of Composers and Publishers (ASCAP) for his “career-long advocacy for American composers and the music of our time.” His Carnegie Hall performance of Samuel Barber’s Antony and Cleopatra was hailed by audiences and critics alike. “The fervent and sensitive performance that Mr. Manahan presided over made the best case for this opera that I have ever encountered,” said the New York Times. Mr. Manahan’s guest appearances include the Orchestra of St. Luke’s and the Jerusalem Symphony Orchestra, as well as the symphonies of Atlanta, San Francisco, Hollywood Bowl, and New Jersey, where he served as acting Music Director for four seasons. He has been a regular guest with the Music Academy of the West and the Aspen Music Festival, and has also appeared with the opera companies of Seattle, San Francisco, Chicago, Santa Fe, Paris, Sydney, Bologna, St. Louis, the Bergen Festival (Norway), and the Casals Festival (Puerto Rico). His many appearances on television include productions of La Boheme, Lizzie Borden, and Tosca on PBS. Live from Lincoln Center’s telecast of New York City Opera’s production of Madame Butterfly, under his direction, won a 2007 Emmy Award. George Manahan’s wide-ranging recording activities include the premiere recording of Steve Reich’s Tehillim for ECM; recordings of Edward Thomas’ Desire Under the Elms, which was nominated for a Grammy; Joe Jackson’s Will Power; and Tobias Picker’s Emmeline. He has conducted numerous world premieres, including Charles Wuorinen’s Haroun and the Sea of Stories, David Lang’s Modern Painters, Hans Werner Henze’s The English Cat, Tobias Picker’s Dolores Claiborne, and Terence Blanchard’s Champion. He received his formal musical training at Manhattan School of Music, studying conducting with Anton Coppola and George Schick, and was appointed to the faculty of the school upon his graduation, at which time The Juilliard School awarded him a fellowship as Assistant Conductor with the American Opera Center. Manahan was chosen as the Exxon Arts Endowment Conductor of the New Jersey Symphony the same year he made his opera debut with the Santa Fe Opera, conducting the American premiere of Arnold Schoenberg’s Von Heute Auf Morgen. == Links on this webpage refer to my interviews

elsewhere on my website. BD

|

|

The Group for Contemporary Music is an American chamber ensemble dedicated to the performance of contemporary classical music. It was founded in New York City in 1962 by Joel Krosnick, Harvey Sollberger, and Charles Wuorinen. It gave its first concert on October 22, 1962 in Columbia University’s MacMillin Theatre. Krosnik left the ensemble in 1963. It was the first contemporary music ensemble based at a university and run by composers. The Group was based at Columbia University from 1962 until 1971, when it took up residency at the Manhattan School of Music. Initial support was provided by the Alice M. Ditson Fund of Columbia, followed later by a broad range of foundations and public sources. The Group’s success led the Rockefeller Foundation to form lavishly-funded "spin-off" ensembles at Rutgers University, the University at Buffalo, the University of Iowa, and the University of Chicago in the middle 1960s. Early supporters of the Group included such Columbia faculty as Jack Beeson, Otto Luening, and Vladimir Ussachevsky. Edgard Varese and Aaron Copland were also among its champions. The early years of the Group were tied in, as well, with the early development of electronic music in the United States. Early on the Group affiliated itself with the Columbia-Princeton Electronic Music Center, and many premieres of important new works involving instruments and electronics by such composers as Milton Babbitt, Mario Davidovsky, and Vladimir Ussachevsky were presented on its concerts. At the heart of the Group were its performers, and a broad range of composers was represented by the Group over the course of its first 25 years. A brief (but not exhaustive) list includes Edgard Varèse, Elliott Carter, Milton Babbitt, Igor Stravinsky, Béla Bartók, Donald Martino, Peter Westergaard, Benjamin Boretz, Otto Luening, Vladimir Ussachevsky, Mario Davidovsky, Goffredo Petrassi, Stefan Wolpe, Ursula Mamlok, Ralph Shapey, Karlheinz Stockhausen, Pierre Boulez, Luciano Berio, Harley Gaber, Alban Berg, Arnold Schoenberg, Anton Webern, Harrison Birtwistle, Peter Maxwell Davies, Ezra Laderman, Raoul Pleskow, Elaine Barkin, Arthur Berger, Yehudi Wyner, Bülent Arel, Joji Yuasa, Tōru Takemitsu, Francisco Kropfl, Jeffrey Kresky, David Olan, Goffredo Petrassi, Aaron Copland, Morton Gould, Frederick Fox, Ross Lee Finney, Roger Reynolds, Robert Stewart, Jacob Druckman, Bernard Rands, Robert Hall Lewis, Claudio Spies, John Harbison, Joan Tower, Chester Biscardi, Carlos Salzedo, Lukas Foss, and Richard Edward Wilson. The Group recorded extensively for a number of labels (CRI, RCA Victor, New World, and later Koch and Naxos) and performed in venues such as the University of Chicago, the University of Iowa, Southern Illinois University, Amherst College, Swarthmore College, Princeton University, the Eastman School of Music, Washington and Lee University, Stony Brook University, Avery Fisher Hall (for the New York Philharmonic), and Rutgers University. The ensemble was awarded a citation from the American Academy and Institute of Arts and Letters in 1985. |

BD: Are you on some of the recordings?

BD: Are you on some of the recordings?|

Drumming is a piece by minimalist composer Steve Reich, dating from 1970–1971. Reich began composition of the work after a short visit to Ghana and observing music and musical ensembles there. K. Robert Schwarz describes the work as "minimalism's first masterpiece." The piece employs Reich's trademark technique of phasing, which is achieved when two players, or one player and a recording, are playing a single repeated pattern in unison, usually on the same kind of instrument. One player changes tempo slightly while the other remains constant, and eventually the two players are one or several beats out of sync with each other. They may either stay there, or phase further, depending on the piece.Schwarz characterized Drumming as a "transitional" piece between Reich's early, more austere compositions and his later works that use less strict forms and structure. Schwarz has also noted that Reich made use of three new techniques, for him, in this work:

|

BD: If you’re presented with the opportunity

of playing a new piece, do you select the minimalist piece, or do you

opt for a Boulez piece, or a Wuorinen piece?

BD: If you’re presented with the opportunity

of playing a new piece, do you select the minimalist piece, or do you

opt for a Boulez piece, or a Wuorinen piece? Manahan: Absolutely one has to leave

something for the performances. If all goes well, you’ve worked

in rehearsal and are working up to a peak, a heightened sense of the

music. But if it’s ideal, you want to plan it so that the best

is yet to come. You don’t peak at the dress rehearsal.

Manahan: Absolutely one has to leave

something for the performances. If all goes well, you’ve worked

in rehearsal and are working up to a peak, a heightened sense of the

music. But if it’s ideal, you want to plan it so that the best

is yet to come. You don’t peak at the dress rehearsal. BD: Were you here for all the

staging rehearsals?

BD: Were you here for all the

staging rehearsals? BD: You say you worked a lot on your diction in this

Susannah. Do you also work on your diction in an Italian

language production, such as Traviata?

BD: You say you worked a lot on your diction in this

Susannah. Do you also work on your diction in an Italian

language production, such as Traviata? BD: Is Stephen Sondheim considered opera?

BD: Is Stephen Sondheim considered opera? Manahan: No, I think he’s wonderful,

because somehow everything still comes out of music. The intent

is still clear. It can be totally out in left field somewhere, but

still he seems in touch with the music. Many directors will superimpose

a concept on top of whatever piece they happen to be doing, and they’ll

force it to work somehow. Then the music seems to just be lost in

the shuffle. That’s when I find it frustrating.

Manahan: No, I think he’s wonderful,

because somehow everything still comes out of music. The intent

is still clear. It can be totally out in left field somewhere, but

still he seems in touch with the music. Many directors will superimpose

a concept on top of whatever piece they happen to be doing, and they’ll

force it to work somehow. Then the music seems to just be lost in

the shuffle. That’s when I find it frustrating.

© 1993 Bruce Duffie

This conversation was recorded in Chicago on October 28, 1992. Portions were broadcast on WNIB in 2001; on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio in 2010; and on WNUR in 2010 and 2018. This transcription was made in 2021, and posted on this website at that time.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website, click here. To read my thoughts on editing these interviews for print, as well as a few other interesting observations, click here.

Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM, as well as on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio.

You are invited to visit his website for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.