A Conversation with Bruce Duffie

BD: Is it especially good for the voice?

BD: Is it especially good for the voice? BD: So Bayreuth should be the pinnacle, then?

BD: So Bayreuth should be the pinnacle, then? HP: I would put it this way. If my year has

four quarters, I devote one quarter for lieder recitals, one quarter for opera,

one quarter for recordings and television, and one quarter for vacation.

But “vacation” is not really a

vacation. Vacation is a kind of working vacation, a training camp to

prepare new things. I don’t appear in public. I am just learning

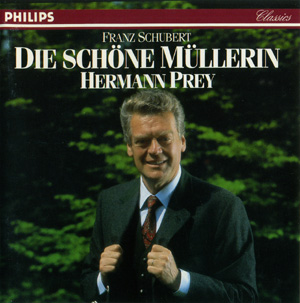

things for the next year, for the next season because many of those Schubert

songs I have never sung in my life. Leonard Hokanson’s my

pianist, and we just prepare the next group of songs. I think there

are about thirty or forty songs I have to sing, and at least half of them

I don’t know; I have to learn them.

HP: I would put it this way. If my year has

four quarters, I devote one quarter for lieder recitals, one quarter for opera,

one quarter for recordings and television, and one quarter for vacation.

But “vacation” is not really a

vacation. Vacation is a kind of working vacation, a training camp to

prepare new things. I don’t appear in public. I am just learning

things for the next year, for the next season because many of those Schubert

songs I have never sung in my life. Leonard Hokanson’s my

pianist, and we just prepare the next group of songs. I think there

are about thirty or forty songs I have to sing, and at least half of them

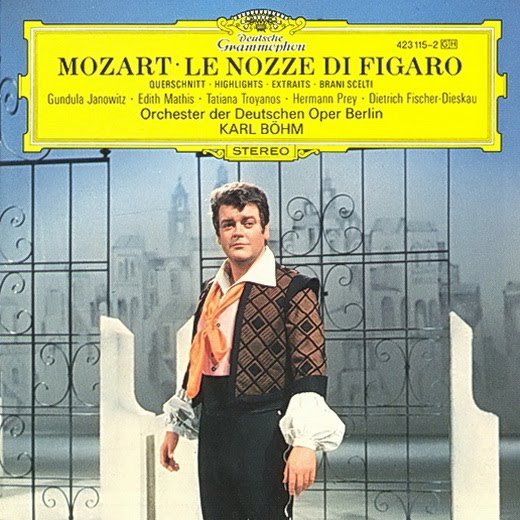

I don’t know; I have to learn them. BD: Tell me about the character of Figaro.

What kind of a man is he?

BD: Tell me about the character of Figaro.

What kind of a man is he? BD: Are they modern women?

BD: Are they modern women? BD: Yes.

BD: Yes.|

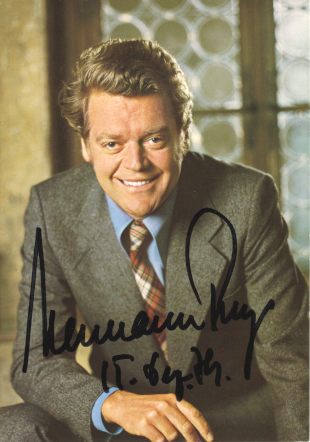

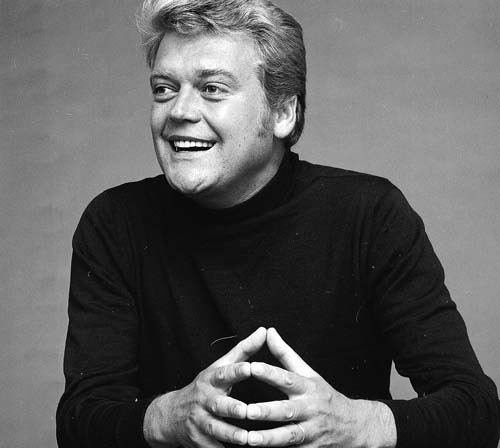

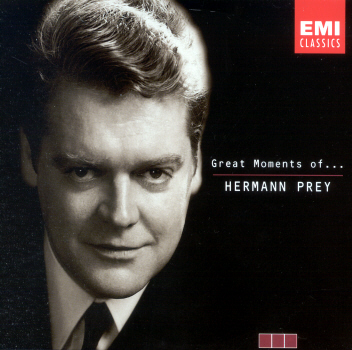

Hermann Prey

Born: July 11, 1929 - Berlin, Germany Died: July 22, 1998 - Krailling, Bavaria, Germany The German baritone, Hermann Prey, grew up during the regime of the National Socialist Party. He was scheduled to be drafted at the age of 15 when the end of the Second World War brought peace and a chance for him to study voice with Gunther Baum and Jaro Prohaska at the Hochschule fur Musik in Berlin. In 1952 he won a contest of Hessischer Rundfunk Frankfurt.  Hermann Prey sang his first Lieder recital in 1952 and the following year

he made his operatic debut as Monuccio in Eugen d'Albert's Tiefland at Wiesbaden. Afterwards he joined

the Hamburger Staatsoper (1953-1960). Since 1956, he appeared frequently at

Berlin and Vienna. In 1959 he debuted at the Bayerische Staatsoper Munich,

as well as at the Salzburger Festspiele (as Barbier in Strauss's Die Schweigsame Frau, which was also Fritz

Wunderlich's debut at Salzburg), where he often sang Guglielmo and Papageno

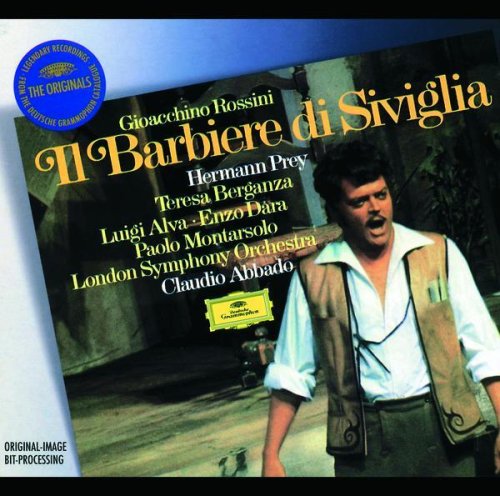

in subsequent years. 1968 he was the protagonist in the Ponnelle/Claudio Abbado

production of Rossini's Barbiere di Siviglia.

Between 1960 and 1970, he performed numerous times at the New York Met, where

he debuted as Wolfram. In 1987, he again appeared at the Met as Musikmeister

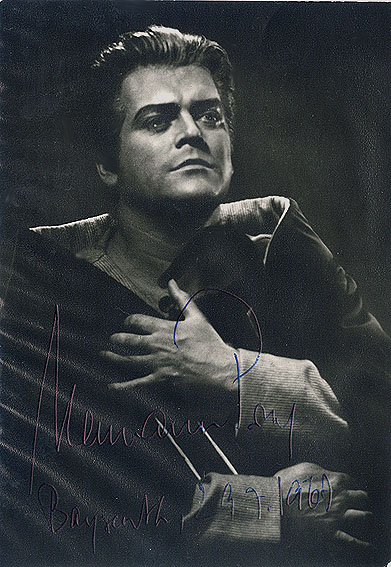

in Ariadne auf Naxos. In 1965, he

debuted at Bayreuth, again as Wolfram. In 1981, he returned to Bayreuth as

Beckmesser. In 1973, he debuted at London as Rossini's Barbiere, and subsequently sang Guglielmo,

Papageno, Eisenstein there. Although he had sung Verdi parts in his early

years, he later concentrated on Mozart and Strauss: Olivier (Hamburg 1957),

Harlekin (Munich 1960), Robert Storch (Munich 1960). In 1997, he sang Sprecher

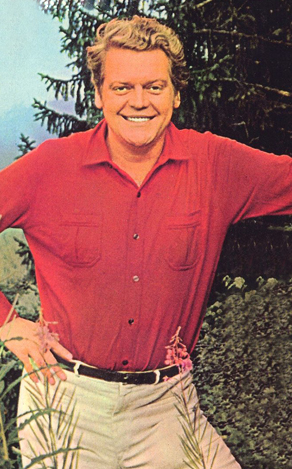

at the Salzburger Festspiele. He frequently appeared in the lighter genres

of Spieloper and Operetta as well as on TV shows, which made him extraordinary

popular in Germany.

Hermann Prey sang his first Lieder recital in 1952 and the following year

he made his operatic debut as Monuccio in Eugen d'Albert's Tiefland at Wiesbaden. Afterwards he joined

the Hamburger Staatsoper (1953-1960). Since 1956, he appeared frequently at

Berlin and Vienna. In 1959 he debuted at the Bayerische Staatsoper Munich,

as well as at the Salzburger Festspiele (as Barbier in Strauss's Die Schweigsame Frau, which was also Fritz

Wunderlich's debut at Salzburg), where he often sang Guglielmo and Papageno

in subsequent years. 1968 he was the protagonist in the Ponnelle/Claudio Abbado

production of Rossini's Barbiere di Siviglia.

Between 1960 and 1970, he performed numerous times at the New York Met, where

he debuted as Wolfram. In 1987, he again appeared at the Met as Musikmeister

in Ariadne auf Naxos. In 1965, he

debuted at Bayreuth, again as Wolfram. In 1981, he returned to Bayreuth as

Beckmesser. In 1973, he debuted at London as Rossini's Barbiere, and subsequently sang Guglielmo,

Papageno, Eisenstein there. Although he had sung Verdi parts in his early

years, he later concentrated on Mozart and Strauss: Olivier (Hamburg 1957),

Harlekin (Munich 1960), Robert Storch (Munich 1960). In 1997, he sang Sprecher

at the Salzburger Festspiele. He frequently appeared in the lighter genres

of Spieloper and Operetta as well as on TV shows, which made him extraordinary

popular in Germany.For all of his fame as an opera star, to many musicians, Hermann Prey is best remembered for his recitals. He gave his first American recital in 1956 and was a regular visitor until the end of his career. He was also a great favorite in Japan. He was especially well known for his interpretations of the songs of Schubert, but he was equally at home with the requirements of many other German and Austrian composers. He was less successful in the few times he moved outside of the German repertoire. Many listeners compare Prey with Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau as a song interpreter, yet their approach to music making was quite different. Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau gives each word and phrase an individual importance whereas Hermann Prey allows the whole composition to unfold as an entity. Both approaches are valid and have their adherents. On the concert stage, Prey was well known for his singing of the Bach Passions and more especially the Brahms Deutsches Requiem. Hermann Prey's voice was a lyric baritone with great warmth and he had complete control of all dynamic variations. He was able to convey a sense of the comic elements of a song without losing the musical sense of the entire piece. He recorded a multi-volume series for Philips to trace the history of German Lieder from the Minnesingers to songs by Reutter and Blacher. His uncountable recordings range from Lieder to opera and oratorio. In 1982, he began teaching at the Musikhochschule Hamburg in order to pass along what he learned about music interpretation. In 1981, he wrote an autobiography Premierenfieber (which was later also issued in English as First Night Fever). In 1988, he directed a production of Le Nozze di Figaro at Salzburg. He was also one of the founders of a Schubert Festival in Austria. His son Florian has also made a career as a baritone singing some of the same roles for which his father was most famous. Hermann Prey will always be remembered for the fine musicianship and the beauty of his voice. -- From the Bach-Cantatas website

|

This interview was recorded in Chicago on October 12, 1985.

Portions (along with recordings) were used on WNIB the following year, and

again in 1989, 1994, 1998 and 1999. This transcription was made and

posted on this website in 2010.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website, click here.

Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM.

You are invited to visit his website for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.