[This interview was recorded in April, 1985. Much of it was

published in The Massenet Newsletter

the following January, hence the emphasis on this repertoire. For

this website presentation, the transcript has been completed, and

pictures and links have been added.]

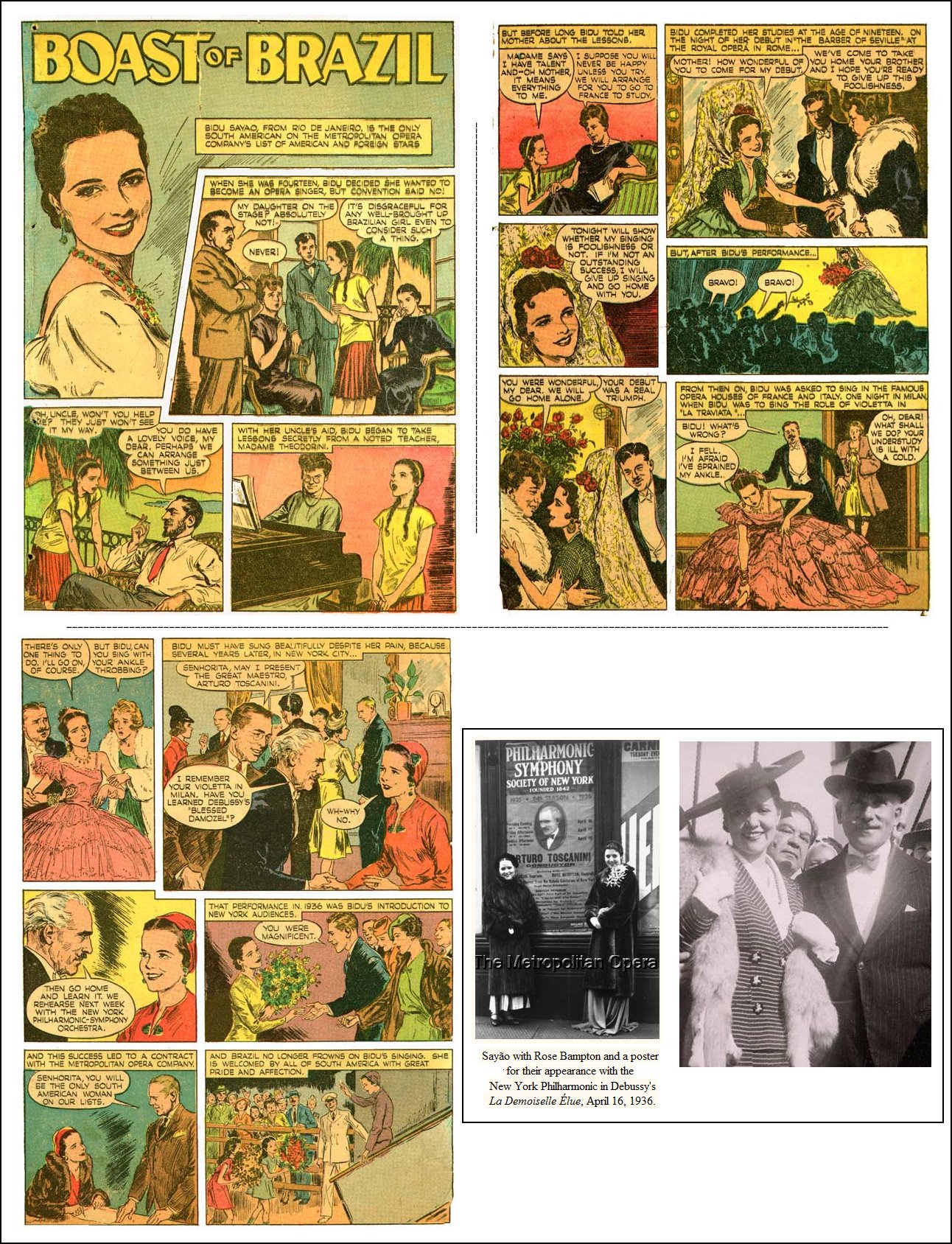

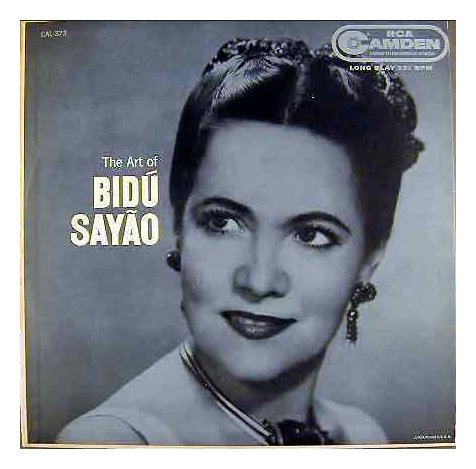

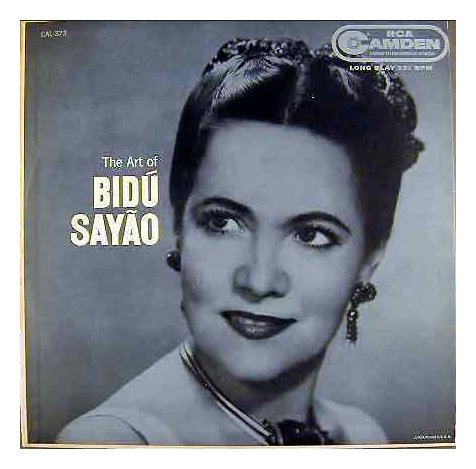

The

Incomparable Bidú Sayão

By Bruce Duffie

“The concert of Bidú

Sayão revealed that the art of Bel Canto has not

entirely vanished. She has a very fine light soprano voice,

remarkably supple, which by careful training is capable of rendering

the most difficult selections of the old repertory with ease and

charm. What makes her talent all the more remarkable is that the

audience never has the impression of effort. She articulates

distinctly, and this is very noticeable when she is singing in

French. Clearness of diction in the French school is a powerful

means of expression, and it was not lacking in her appearance.”

So wrote Louis Schneider of the New

York Herald in 1924 under the headline “Music

in Paris.” That review, perhaps more than

anything else, sums up the special qualities of Bidú

Sayão.

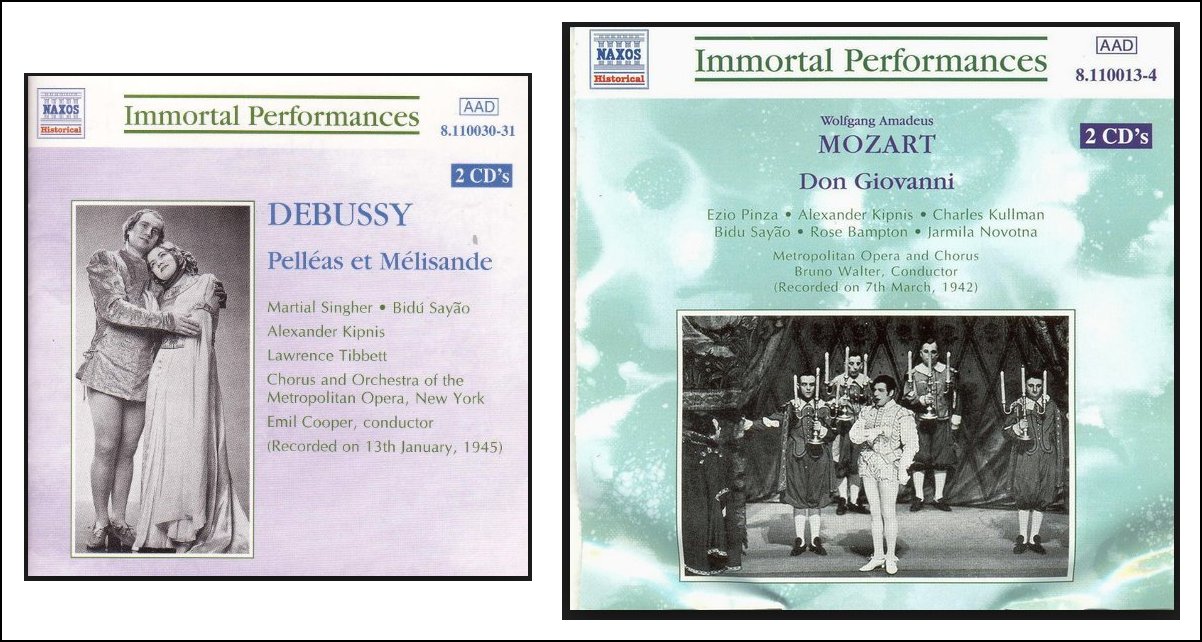

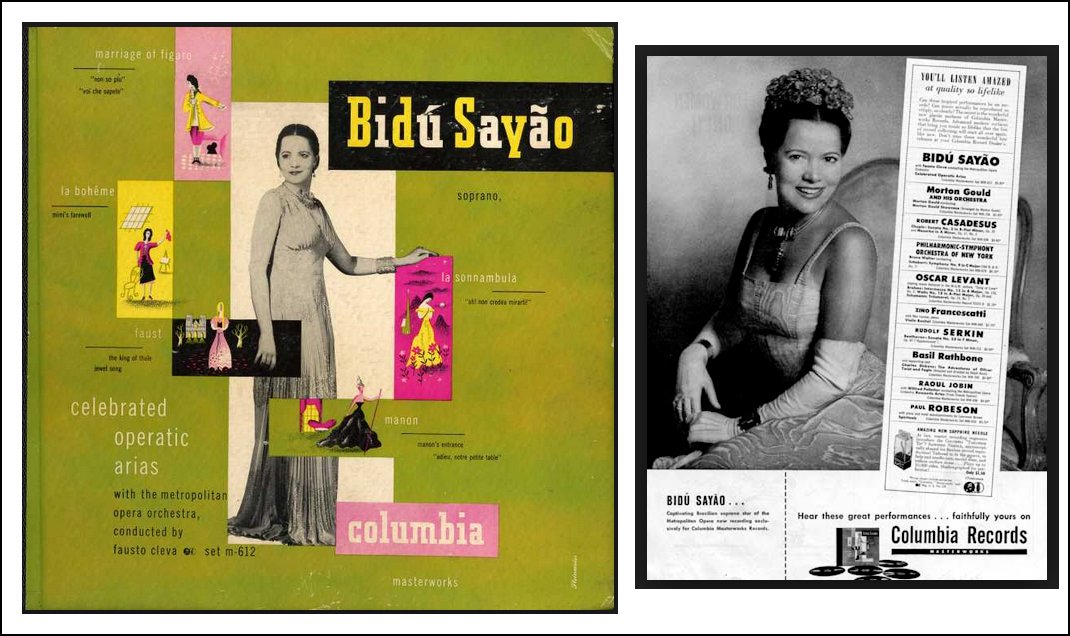

She had a great career, and a long one because she knew what she could

and should do — and more importantly what she

could and should not do. But throughout, she had a series of

positive peaks. Appearances in both opera and concert all over

the world brought her artistry to many people. The 1954 edition

of The Grove Dictionary notes

that in 1945, Sayão was second in a

contest to find the most popular singer in the U.S.A. Now, her

legend lives on in studio recordings and broadcasts. Her version

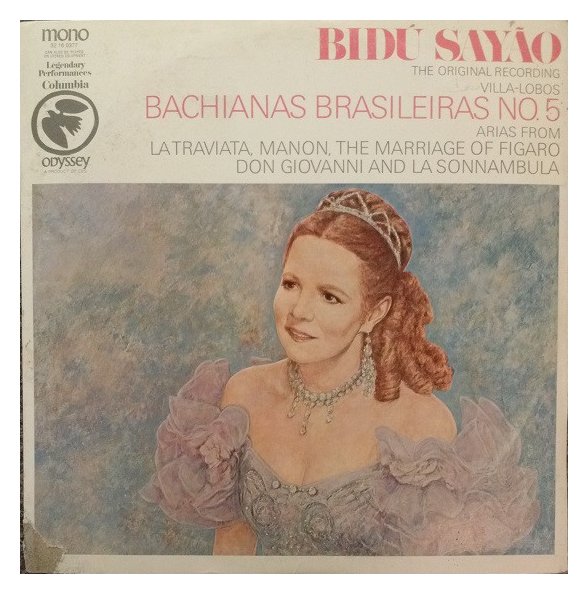

of the Bachianas Brasileiras #5

has been voted into the Recording Hall of Fame, and the Metropolitan

Opera celebrated its Centenary by issuing the 1947 broadcast of Roméo et Juliette.

Over the course of her brilliant career, she appeared with most of the

legendary singers and conductors. She learned from those who went

before, and now tries to pass along what she can to those who are eager

to learn. Several months ago, it was my very great fortune to

have her respond to my request for an interview. She permitted me

to call her on the telephone, and she was gracious, interesting, and

animated throughout the hour.

Here is what was said . . . . . . . . .

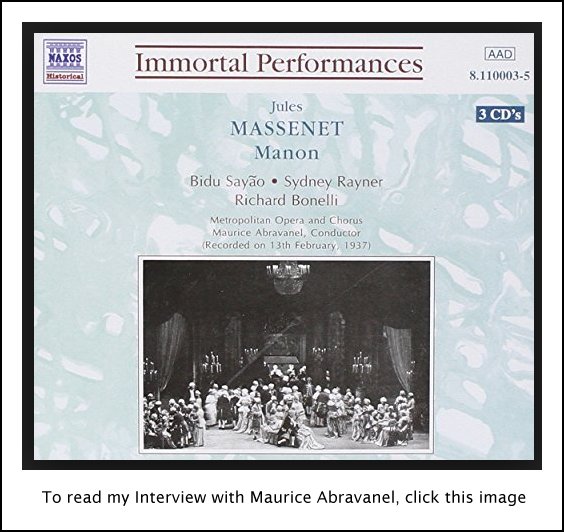

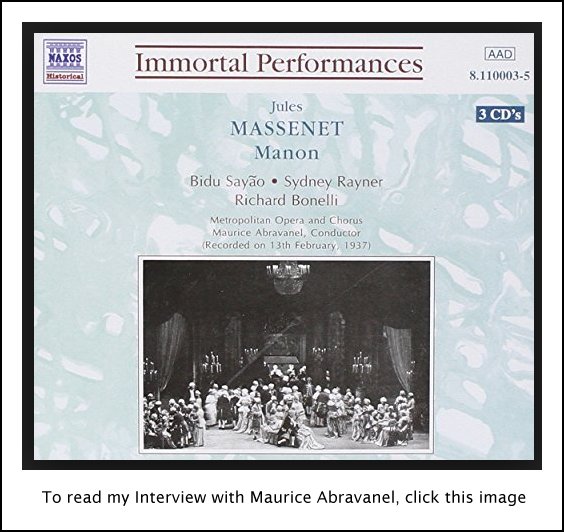

Bruce Duffie: Let’s

start out with one of your most famous roles. Tell me about Manon.

Bruce Duffie: Let’s

start out with one of your most famous roles. Tell me about Manon.

Bidú Sayão:

I studied the role in Paris, and was very fortunate to meet the

granddaughter of Massenet. She was a wonderful old lady, and

helped me a lot with the tradition of the opera. She put me in

the hands of the man who created the role of Lescaut. He knew all

the traditions of the opera, and it was terrific for me to learn the mise-en-scène, and the way

we should behave on the stage in that role. I learned all the

details that were wonderful for a young singer like I was at that

time. After that, I started singing that opera all over.

BD: When you sang

it in different theaters, did you keep the same traditions?

Mme. Sayão:

The productions were sometimes different — especially

in the big theaters — but the interpretation was

the same. For instance, the version which I learned was in the

Opéra Comique, a tiny theater with beautiful and intimate sets.

BD: How does that

role compare with others you sang?

Mme. Sayão:

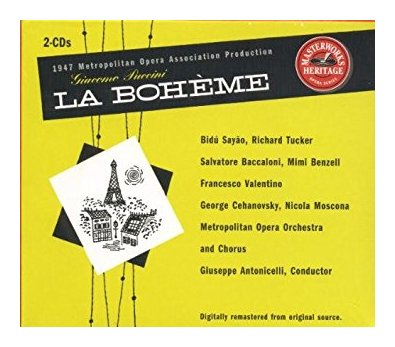

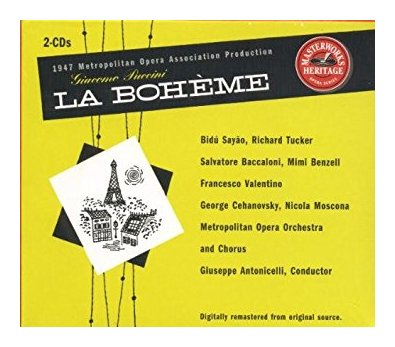

That is one role that I love, but I also like Mimì in Bohème, Juliette in Roméo et Juliette, and

Violetta in Traviata. I

like more than just soubrette roles. My repertoire as a lyric was

very small because my voice was very light. When I started, my

voice had a tendency to go up, so I became a coloratura for many

years. Then, with a strong will, I could reach a little bit of

the lyric repertoire. But because I never forced my voice, I

could go on for thirty years of career. I would have liked to

sing all the Puccini operas, but they were too heavy for me, so the

only one I could touch was Bohème.

BD: You were very

smart to do only roles which suited your voice.

Mme. Sayão:

That is it. That is what I preach to the new singers of

today. “Never start with the heavy

repertoire, even if your voice is big. Go slowly and begin with

the lyric roles, and after you get to a certain age, you can touch the

dramatic roles.” But they are anxious and

want to do everything fast.

BD: How can we get

the young singers to slow down and conserve their voices?

Mme. Sayão:

We live in another era than I did. Today we have TV, and

everything must be televised. In my day, an opera or recital was

given to just a few people, but on the TV, millions and millions of

people can hear and see, and you can become a star with one

performance. With us, it took years to reach the heights of

popularity.

BD: It took fifteen

years to become an overnight sensation!

Mme. Sayão:

[Laughs] That is it. The only thing we had was radio.

Late in my career, I did a little bit of TV with Firestone and the Telephone Hour.

BD: Is it a good

thing that operas are now being televised?

Mme. Sayão:

I think so. People get more familiar, and they become curious and

come to the theater to see it live.

*

* *

* *

BD: Tell me about

singing for Jean de Reszke.

Mme. Sayão:

After leaving my teacher in Romania, Mme. Theodorini, I went to Paris

to have what we called a master-class. Today, people who know

they want to sing go to a teacher and say they have a

master-class. But a master-class is when you are ready and you

need to be polished. So I went and auditioned for Jean de

Reszke. He did not accept pupils without hearing them. He

accepted me, and I went to Nice and studied with him the last two years

of his life. I learned all the chamber music because I thought I

would be a recitalist. But he felt that I should be on the stage

rather than do recitals, so he taught me Juliette, and Ophelia in Hamlet. I never did sing

Ophelia on the stage — just the aria. But

I protested that I would never get the opportunity to sing Juliette

because my voice was too small. But he told me to learn all I

could about it because one day I would sing it in France. Years

later I did with Georges Thill, and for the centennial of the Met, they

chose the broadcast of this opera (with Jussi Bjoerling) to release on

records.

BD: Are you pleased

that this performance is now available to the public?

Mme. Sayão:

I think so. Of all the broadcasts, they chose that one. So,

I guess they liked it, also.

BD: Let’s

come back to Manon. What kind of character is she?

Mme. Sayão:

I liked to sing Manon very much. It was perhaps not my very

favorite role, but it was one I liked to sing very much because I had

studied it so carefully. It is a difficult role. In other

roles, the leading character is more or less the same from the first to

the last. But Manon changes in every act. She is a

different person [as seen in the pair

of photos below]. She starts out just like a little girl

who should go to the convent, and after she finds this boy, she went

with him to Paris. In the second act she has already lived with

him as his mistress, but she wants the luxuries. Even in the

first act she sees ladies with their jewels. She was a very

ambitious woman. She would give everything for luxury and a

beautiful life.

BD: Is her problem

that she doesn’t know whether she wants love or

luxury?

Mme. Sayão:

That is it. In the beginning, she didn’t

love Des Grieux enough. She gets the other proposition to be a

big lady, and have a palace and jewelry and everything she wants, so

she leaves him. In the third act, she comes out for the

Cours-la-Reine. In many productions they cut that scene, but it

is very important. In the promenade, she dresses like a queen and

sings and dances a minuet. That is her life, and her lover has a

beautiful ballet in her honor. But she still loves Des Grieux and

leaves all the luxury to rush to St. Sulpice to seduce him again.

That is a beautiful duet. But you see she is changed. Every

scene she is a different woman. Finally, after all the asking and

touching and kissing, he gives up. But he hasn’t

enough money to sustain her luxury, and his father doesn’t

want to give him money for her. So they go to gamble, and she’s

yet another woman who now wants money and more money. Then,

through complications with her ex-lover, she winds up being accused and

going to prison. All this is in the Massenet version.

Puccini doesn’t have all these scenes, so the

Massenet is more complete for me. Then, in the last act, when she

is about to die, she becomes really human. She dies in his arms

and tells him she understands what she did. She was frivolous, so

superficial, so ambitious, and she finally realizes that he was really

her love, but it’s too late. These are

important moments in Manon but she changes every minute.

Mimì or Violetta are always what they are, but with Manon, the

feeling changes a lot, and the interpretation changes a lot.

BD: Is that a

French tradition, to show the character development?

Mme. Sayão:

Yes. The Italian tradition is much more dramatic and much more

mature. I don’t know why, but Puccini just

couldn’t write something like champagne. Madame Butterfly is dramatic, and

the orchestration is so heavy, but she was only fifteen years

old. There are many roles I would have loved to have sung, but

God gave me a small voice which I couldn’t

change. I didn’t care so much for Elixir of Love, or Don Pasquale, but I studied them

very hard and they said that I was OK. I was a soubrette and did

things like that. I tried them, but I didn’t

like so much to be a soubrette. They called Susanna in Marriage of Figaro a soubrette, but

I never played her that way. I played Susanna just like a woman

in love with her husband-to-be. She did the little tricks to

please her boss, the Countess. It was funny since I played Rosina

before she was married (in Barber),

and then played her maid in the Mozart opera. I liked very much

Zerlina, and that one is called a soubrette, but I call her bright and

full of life, and very much in love. So I don’t

call that a real soubrette. It is a small role, but it has very

nice arias and duets and was very pleasant. Susanna is a

difficult role because you must make that role. If you don’t

act it well and sing it well, it’s a very

ungrateful role because she is on the stage constantly from the

beginning to the end. Only in the last act does she get her

beautiful aria, Deh vieni non tardar.

Before that, all the other characters have beautiful arias.

Susanna has little duets and things, but not any big aria like the

others. So sometimes the audience is tired, and the critics have

gone because it’s late, and then she has her

beautiful aria.

BD: Is Susanna in The Marriage of Figaro a little

like Rosina was in The Barber of

Seville?

BD: Is Susanna in The Marriage of Figaro a little

like Rosina was in The Barber of

Seville?

Mme. Sayão:

Yes, that’s correct — a little

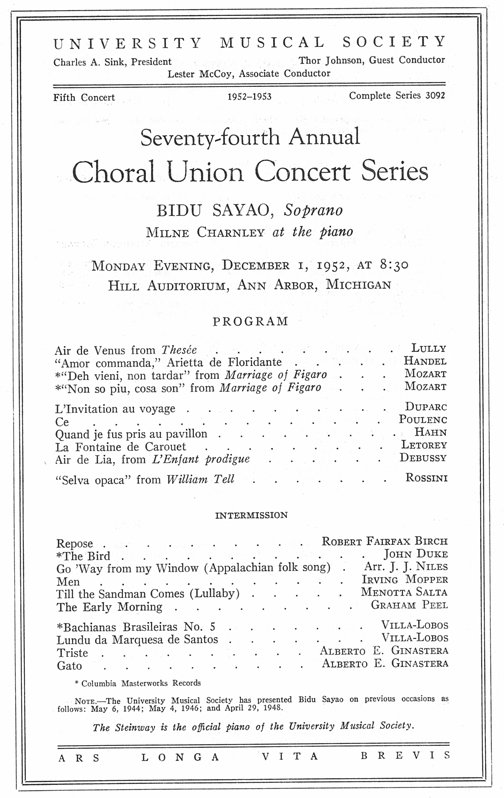

Spanish girl full of life. I also loved very much recitals.

BD: More than opera?

Mme. Sayão:

[Hesitating] Almost. I loved recitals because I was alone

and could sing in different languages. I could express with my

face all the beautiful words. I sang some operatic arias

sometimes because the audience asked so much for them, but I was very

well-prepared, especially in the French repertoire. I also sang

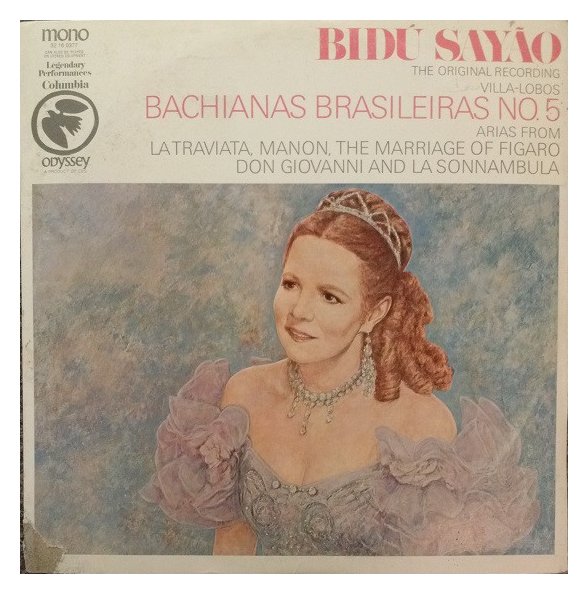

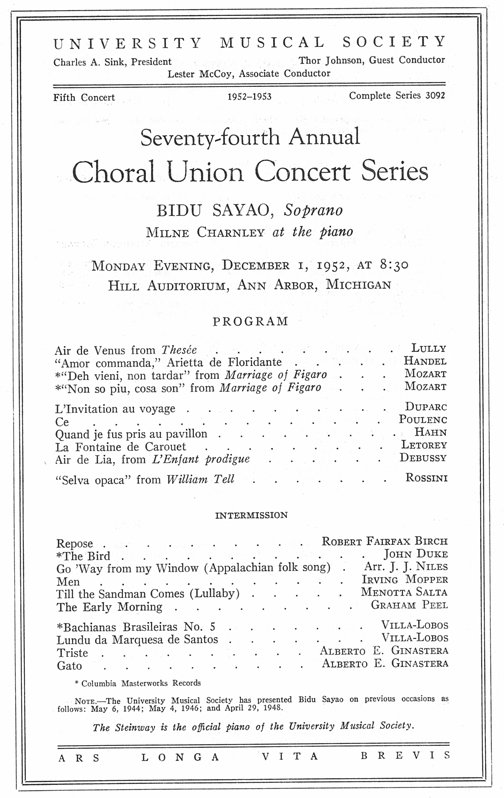

lots of Spanish things, and I did lots of Villa-Lobos. [A typical program is shown later on this

webpage.] The recording I made of Bachianas Brasileiras #5 won an

award. They gave me a beautiful scroll. I am happy that now

all the sopranos perform and record this work.

BD: Your recording

with the composer is one we often play on WNIB.

Mme. Sayão:

He created that for me! I heard it in Brazil in the original

version for eight ’celli and solo violin.

It was not for voice at all, but I fell in love with the melody and

wanted to sing it. Villa-Lobos said no, but I said yes, and here

in America he made the arrangement. He wrote some words himself

for the middle part, and said I could hum the other sections, with the

mouth closed and the sound coming from the nose. He wanted to

make a recording to see how that would sound, so he could decide if I

could take it around on my concerts. That is the record that we

made, and after that, everyone started to sing it because it is so

beautiful.

*

* *

* *

BD: What is your

opinion of the current group of singers?

Mme. Sayão:

Thank God we have many beautiful singers today. After this

generation, what will happen I don’t know, but we

still have beautiful voices today. We don’t

have as many as in my time, but there are still some good voices.

BD: Do you feel

that we are losing a tradition?

Mme. Sayão:

Well, ‘tradition’ is a

word that doesn’t exist anymore. I heard

the tradition because the generation before mine was all

celebrities. I learned with them to listen, and went to them for

advice, but today we don’t find this any

more. The new singers don’t go to the old

singers and ask advice. Sometimes I go to the opera and I don’t

enjoy the new productions which are so different from my time.

Today the star is the director. We see Zeffirelli and Ponnelle,

and after that comes the conductor, and then come the singers.

People today go for the production and they don’t

care if it’s a good singer or a star singer or a

mediocre singer. For them it’s the

same. In my time, during the war, the Metropolitan was so poor

that the sets were in pieces. The only new production during the

regime of Edward Johnson was Marriage

of Figaro. He had the production built and gave us the

costumes. This was the only one where we did not wear our own

costumes. Normally we never used any costumes from an opera

house. We had our own — from the wigs to

the shoes. Today the singers are so fortunate because they don’t

put one penny in any costumes, and they are gorgeous. They cost

fortunes and the singers get them for nothing.

BD: But isn’t

the production more unified if one person has designed the sets and the

costumes?

Mme. Sayão:

Today, the costumes go with the production, and the artists lose their

personality. The stage directors teach you every movement, every

step, everything you do. If you have to take a glass of water,

you have to do it the way that want you to do it. I never could

have worked with them because I was an instinctive actress. I had

my personality, and my colleagues were the same. Certainly, when

we would rehearse we’d know which door to come

from and which door to go out, and where we’d

find our colleagues, but the interpretation, the movements, were

ours.

BD: So you would

learn the role and the interpretation, and not expect the opera house

to give you much direction?

Mme. Sayão:

Yes. Today, the directors are the stars, and they want the

artists to move in a certain way. Sometimes the artists don’t

feel it that way, and when you don’t feel it that

way, how can you be spontaneous and real? I don’t

think it’s possible. I’m

very happy I’m retired because I couldn’t

work in this way at all.

BD: Did you ever think

of directing an opera yourself?

BD: Did you ever think

of directing an opera yourself?

Mme. Sayão:

[Laughing] No, never, never! I have no ambitions of

that. I was spoiled because in my time I heard the greatest

Toscas, the greatest Aïdas, the greatest Traviatas, and everything

was so wonderful. We would go for the artists, not for the

scenery or the stage. We would go for the music — for

the conductors and for the composers and for the singers.

BD: Is there any

way to strike a balance with great scenery and great singing?

Mme. Sayão:

Perhaps. We still have great singers today — not

too many, but some are first-class. There are not too many

tenors, but we do have Domingo, Pavarotti, and Alfredo Kraus whom I

admire immensely. We also have mezzos and sopranos who are

first-class, very beautiful, but I don’t want to

mention names because I might leave one out!

BD: So we don’t

have a lot of great singers these days?

Mme. Sayão:

No, not a lot.

BD: But we have a

lot of singers!

Mme. Sayão:

Oh yes. Everybody sings! I serve as a judge for auditions

and there are hundreds and hundreds of singers. It’s

a kind of an epidemic.

BD: Then why are we

not finding so many great ones?

Mme. Sayão:

I don’t know. Many times I hear a beautiful

voice, but they don’t sing well. They don’t

feel, they don’t interpret. Perhaps we don’t

have enough good teachers. I don’t

understand it. I don’t want to hurt the

feelings of the new generation because they are so intelligent,

extremely intelligent people. They sing in many languages with

much facility. They are so musical and they have beautiful

voices, but they will never become big stars like Joan

Sutherland, or Marilyn

Horne, or Leontyne Price. They are singers, but not

artists. I make a distinction there. To be an artist is

very difficult — much more difficult than just

to sing.

BD: What is it that

makes an artist?

Mme. Sayão:

It’s something you cannot learn. You must

be born with it. You must sing with your heart and your soul more

than with your brains and vocal cords. It must all come together,

but from the heart. You express everything you say. Often

there is a lack of diction. They don’t pay

attention to the words they say. When it comes from your heart,

the words make the interpretation. Opera is drama or comedy, but

it is theater. I always used to say that opera for me is just

like magic, illusion, poetry, passion, humanity, and fantasy. If

you have all of these, then you make opera and it is delightful.

Otherwise it can be very boring.

*

* *

* *

BD: Does opera work

in translation?

Mme. Sayão:

Some — the ones with lots of recitatives.

Now they have those titles they put on top of the stage. I’ve

not seen them, but they use them at the New York City Opera and in San

Francisco. Terry McEwen [then

the Manager of the San Francisco Opera] says they are a terrific

success because people can read it in English while they sing in

Italian or in French or in German.

BD: This coming

fall we will get our first look at them here in Chicago.

Mme. Sayão: I’ve

never seen them, but I have the impression that if I start to read, I

will lose what goes on onstage. Just like when I see a movie in a

language I don’t understand, I read the

translation and I lose so much of the acting because my eyes are with

the words. This is just my own impression, and I may be

completely wrong, so I am very curious to see a performance with those

subtitles. But operas with lots of recitatives could use it, and

also the Wagner operas with so much talking. I don’t

speak or understand German, and I want to know what Wotan says to

Fricka and all those big, big conversations. If I understood it,

I would enjoy it much more. So I guess that for people who don’t

understand Italian or French, having it in English helps a lot.

But for Verdi or Puccini or even Massenet, people go to see those

operas and they read the libretto ahead of time, so they know the

story. It’s so funny to hear those in

English. At the Opéra in Paris, I sang Rigoletto in French, and it was the

most horrible thing you could imagine! I also sang Bohème in French at the

Opéra Comique, and it was very bad. The translations are

terrible.

BD: As an artist, how

much preparation do you expect from the audience?

BD: As an artist, how

much preparation do you expect from the audience?

Mme. Sayão:

I imagine that the audience should be prepared when they go to an

opera. They may not be musically literate, but they should at

least know the story, to know what goes on. Then if you like the

music, you will come back and become a fan. I have the impression

that the new audience today doesn’t have the

tradition from the past, so they go to see the spectacle. The

Metropolitan can take a risk with these lavish productions. In

their new production of Tosca,

they change the set in front of your eyes just like magic! It is

really marvelous. Other operas are just as good, but other

theaters will not be as good because they don’t

have this kind of machinery.

BD: You saw this Tosca live in the theater?

Mme. Sayão:

Yes, I went to the premiere.

BD: Did you also

see it on television?

Mme. Sayão:

Yes, and it lost a lot. We have a small screen, so everything is

reduced. You see just a little part, but in the theater you see

everything. The singing and the acting were OK, but the scenery

was not the same as it was live in the theater.

BD: Are you

optimistic about the future of opera?

Mme. Sayão:

I think so, but we need new composers. Right now opera is living

on the old composers. When they give Verdi or Puccini or Massenet

or Wagner, it is sold out. But when a new work is given, the

theater is not sold out. So we need composers who write beautiful

things — not just recitatives and things we don’t

understand, but things with melody for everybody. They are

writing operas these days, but, for instance, I saw Lulu. I like the play, but

the music I didn’t understand. It’s

very atonal. There were no arias or duets, just recitative and

talking with the notes [sprechstimme].

But I am old-fashioned... [Both laugh]

BD: There’s

nothing wrong with being old-fashioned! Let me go the other

way. Is there a place on the stage today for Handel operas?

Mme. Sayão:

Oh yes. Now is the tri-centennial, but in the time of Handel and

Gluck and Mozart, and all those great, great geniuses, the opera houses

were small. There were only a few in the orchestra and the

singers were specialists in that technique. The important thing

was the technique. Handel is full of agility and cadenzas, more

than even big lines of melody. The singers were trained just like

a violinist or cellist or flutist. They were human

instruments. Today we don’t have those

little tiny opera houses. They showed the opera house of that

time in the film Amadeus.

How can we get voices today like Malibran and Pasta and Grisi? We

don’t know just what they sounded like, and they

only sang in small theaters with small orchestras, and did not risk

their voices in big places with big orchestras. So perhaps those

voices were not as big as we think they were.

BD: Then does opera only

belong in a small house?

Mme. Sayão: They

only began to build big houses at the end of the nineteenth

century. Before that, the opera houses mostly belonged to the

kings and emperors. They had their own opera houses, and the

composers wrote for those spaces. When you play The Secret Marriage by Cimarosa, it

needs a smaller theater. I sang that work very often

in Italy. It is a jewel just like Mozart, but it needs a smaller

theater. When you put those kinds of operas on in the

Metropolitan or the State Opera of Vienna or La Scala, they lose so

much. Even if the acoustic is good, the intimacy is lost.

The movements and expressions of your face are lost in the big opera

houses. In Italy, they have the Piccola Scala which is a small

opera house, and they used to give those works there.

BD: We have a small

theater, the Civic Theater, which is right next door to the big house,

and everybody wishes they would do more in that house. The Opera

School of Chicago has done some works there, including The Secret Marriage! [The Opera School of Chicago was

established in 1973, and among its earliest productions were some newer

works such as The Rakes Progress (Stravinsky), The Turn of the

Screw, and The Rape of

Lucretia (Britten), as well as Il

Ciarlatano [The Charlatan] by

Domenico Puccini (1772-1815), the grandfather of the well-known verismo

composer.]

BD: We have a small

theater, the Civic Theater, which is right next door to the big house,

and everybody wishes they would do more in that house. The Opera

School of Chicago has done some works there, including The Secret Marriage! [The Opera School of Chicago was

established in 1973, and among its earliest productions were some newer

works such as The Rakes Progress (Stravinsky), The Turn of the

Screw, and The Rape of

Lucretia (Britten), as well as Il

Ciarlatano [The Charlatan] by

Domenico Puccini (1772-1815), the grandfather of the well-known verismo

composer.]

Mme. Sayão:

Handel and all those things would be perfect in that kind of small

house.

BD: Did you change

your technique at all when you sang in different sized houses around

the world?

Mme. Sayão:

Oh, no, no! I always sang with what I had. It is the

acoustic that counts the most. Even though my voice was not big,

everybody could hear me in all the opera houses I sang, thank

God. But this was because I had good schooling, and I studied

very hard, and I succeeded. The new Metropolitan seems very good,

but in the old Met, there were spots which were very good and you could

hear very well. Chicago has very good acoustics, and I loved

singing there very much. I think it is very good, and everybody

said so.

BD: What about the

two houses in Paris?

Mme. Sayão:

Oh they had beautiful acoustics. The Opéra Comique was

small, just the size I told you for those older works. The big

Opéra had so much rococo design. There were too many

draperies and too much crystal. It was too heavy, but even so,

the acoustic was good. In Italy, every opera house was beautiful,

and in South America, too, especially the Colón in Buenos

Aires. There you could whisper. You can hear the most

delicate sound. In my country of Brazil, we have a small theater,

but the acoustic is beautiful. It is a very pretty opera house,

all marble and bronze. Everything is very pretty.

BD: Tell me more

about singing here in Chicago.

Mme. Sayão:

I used to sing in Chicago [Barber in

1941; Pelléas (the

first performance in Chicago since Garden in 1931) and Traviata (wearing a gown in the first act studded

with what were reputed to be diamonds from her family’s diamond mines

in Brazil, according to Opera in Chicago by Ronald Davis) in 1944; Manon and Traviata in 1945], and when the

Lyric Opera of Chicago re-opened in 1954, I was almost retired from the

Met, just doing recitals, but Carol Fox convinced me to be in the cast

of Don Giovanni with Rossi-Lemeni.

Carol had been my friend for many years in New York, so I could not say

no to her. I sang Zerlina for the opening night, and it was a

beautiful evening. [A photo of

the full cast is on the webpage with the Interview of Rossi-Lemeni

(linked above).] I will never forget that. I love

Chicago and I love the audience. They are so wonderful.

BD: Was it special

for you knowing that you were opening a new company?

Mme. Sayão:

Yes, I thought it was very important. I then came back to

celebrate her 25th anniversary with the opera. It was a gala with

a beautiful dinner, and I was introduced on the stage. I never

saw such a gala in my life! I met many old friends of mine.

BD: Thank you so

much for speaking with me today. You have been most gracious.

Mme. Sayão:

Thank you for calling me.

© 1985 Bruce Duffie

This conversation was recorded on the telephone on April 1,

1985. A portion was published in the Massenet Newsletter in January,

1986. Portions were broadcast on WNIB in 1987 and 1997.

The transcription was completed and slightly re-edited in 2017, and

posted on this

website

at that time.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been

transcribed and posted on this website, click here.

Award

- winning

broadcaster

Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975

until

its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His

interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since

1980,

and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM, as well

as

on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio.

You are invited to visit his website

for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of

other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also

like

to call your attention to the photos and information about his

grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a

century ago. You may also send him E-Mail

with comments, questions and suggestions.

Bruce Duffie: Let’s

start out with one of your most famous roles. Tell me about Manon.

Bruce Duffie: Let’s

start out with one of your most famous roles. Tell me about Manon.

BD: Is Susanna in The Marriage of Figaro a little

like Rosina was in The Barber of

Seville?

BD: Is Susanna in The Marriage of Figaro a little

like Rosina was in The Barber of

Seville?

BD: Did you ever think

of directing an opera yourself?

BD: Did you ever think

of directing an opera yourself? BD: As an artist, how

much preparation do you expect from the audience?

BD: As an artist, how

much preparation do you expect from the audience? BD: We have a small

theater, the Civic Theater, which is right next door to the big house,

and everybody wishes they would do more in that house. The Opera

School of Chicago has done some works there, including The Secret Marriage! [The Opera School of Chicago was

established in 1973, and among its earliest productions were some newer

works such as The Rakes Progress (Stravinsky), The Turn of the

Screw, and The Rape of

Lucretia (Britten), as well as Il

Ciarlatano [The Charlatan] by

Domenico Puccini (1772-1815), the grandfather of the well-known verismo

composer.]

BD: We have a small

theater, the Civic Theater, which is right next door to the big house,

and everybody wishes they would do more in that house. The Opera

School of Chicago has done some works there, including The Secret Marriage! [The Opera School of Chicago was

established in 1973, and among its earliest productions were some newer

works such as The Rakes Progress (Stravinsky), The Turn of the

Screw, and The Rape of

Lucretia (Britten), as well as Il

Ciarlatano [The Charlatan] by

Domenico Puccini (1772-1815), the grandfather of the well-known verismo

composer.]