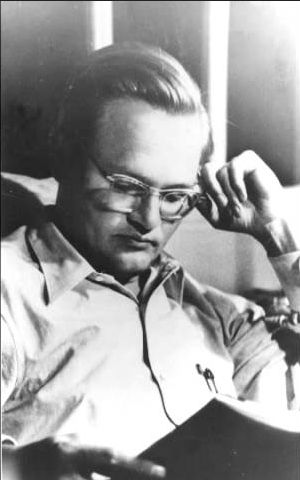

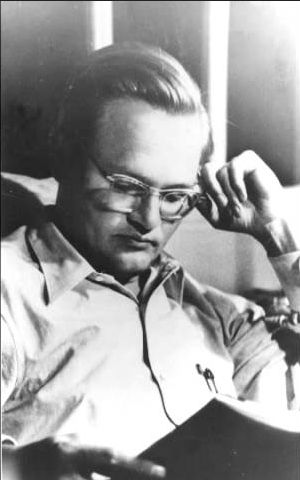

Robert Kurka, of Czech descent, was born in Cicero, Illinois

(just outside Chicago) on December 22, 1921. He attended Columbia University,

but was largely self-taught in composition, studying only briefly with

Otto Luening and

Darius Milhaud. After graduating from Columbia in 1948, Kurka taught at

the City University of New York and Queens College, served as composer-in-residence

at Dartmouth College, and composed to growing acclaim.

He received a Guggenheim Fellowship in 1951, after completing a chamber

symphony, a symphony for brass and strings, a violin concerto, four string

quartets, two violin sonatas, and several other works. An award from the

National Institute of Arts and Letters came the following year.

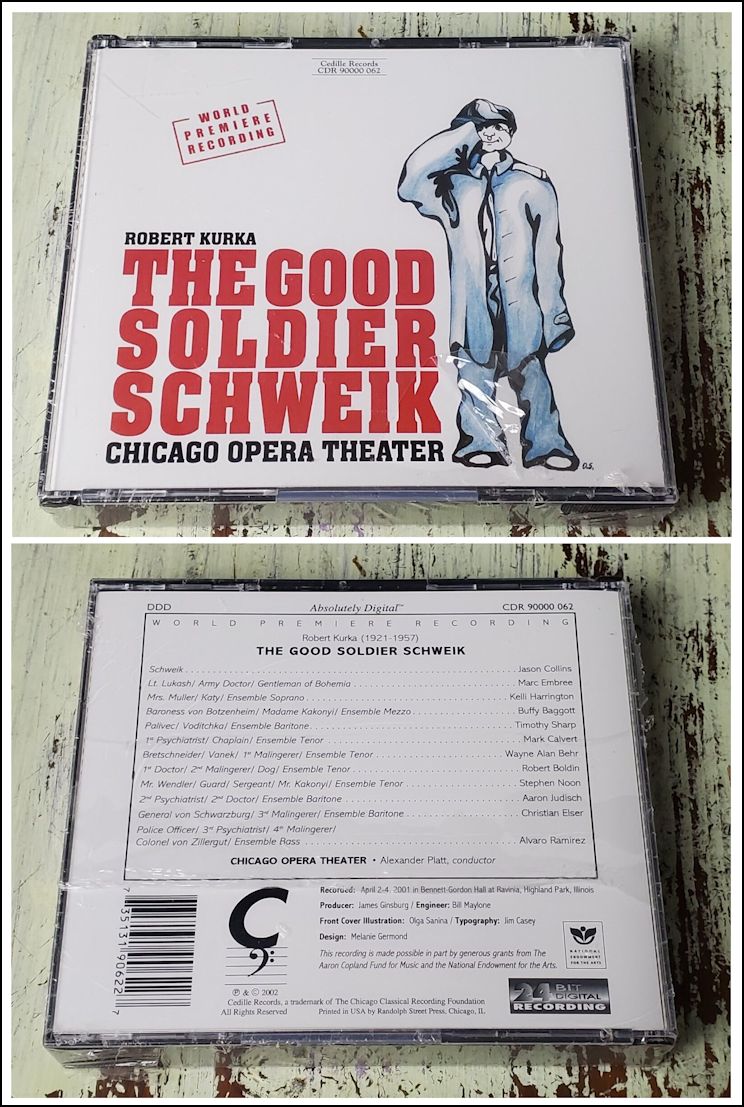

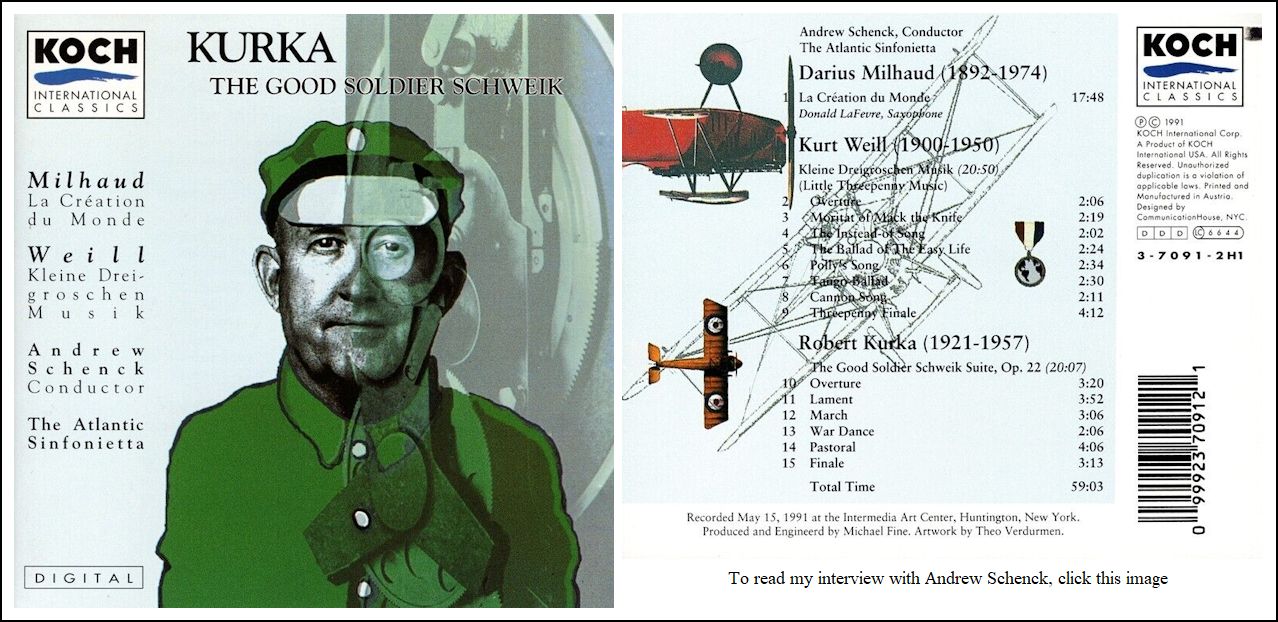

In 1952, he began an opera based on Jaroslav Hasek’s satirical novel

The Good Soldier Schweik, but had difficulty securing rights to make a libretto

from it, so instead worked his sketches into the orchestral suite that

has become his best-known composition. Eventually he proceeded with the

opera, but he was stricken with leukemia as he worked on the score. He

was able to finish it sufficiently before his death in New York on December

12, 1957 – ten days before his 36th birthday – that composer and arranger

Hershy Kay could prepare the work for its premiere, given with considerable

success by the New York City Opera on April 23, 1958. The declaration

accompanying an award Kurka received from Brandeis University on May 5,

1957 (seven months before his death) proved sadly ironic: “To Robert Kurka,

a composer at the threshold of a career of real distinction.”

|

Harry Silverstein has been the Director of DePaul Opera Theatre since

1990 and instructs singers in performance techniques. Mr. Silverstein has

professionally directed over 100 productions of 45 operas on 4 continents,

including such theaters as Lyric Opera of Chicago, San Francisco Opera,

English National Opera, and companies in England, Northern Ireland, Germany,

The Netherlands, Australia, New Zealand, and Brazil, as well as more than

15 American companies including Lyric Opera of Chicago, New York City Opera,

Dallas Opera, Houston Grand Opera, Washington National Opera and Seattle

Opera.

Harry Silverstein has been the Director of DePaul Opera Theatre since

1990 and instructs singers in performance techniques. Mr. Silverstein has

professionally directed over 100 productions of 45 operas on 4 continents,

including such theaters as Lyric Opera of Chicago, San Francisco Opera,

English National Opera, and companies in England, Northern Ireland, Germany,

The Netherlands, Australia, New Zealand, and Brazil, as well as more than

15 American companies including Lyric Opera of Chicago, New York City Opera,

Dallas Opera, Houston Grand Opera, Washington National Opera and Seattle

Opera.