|

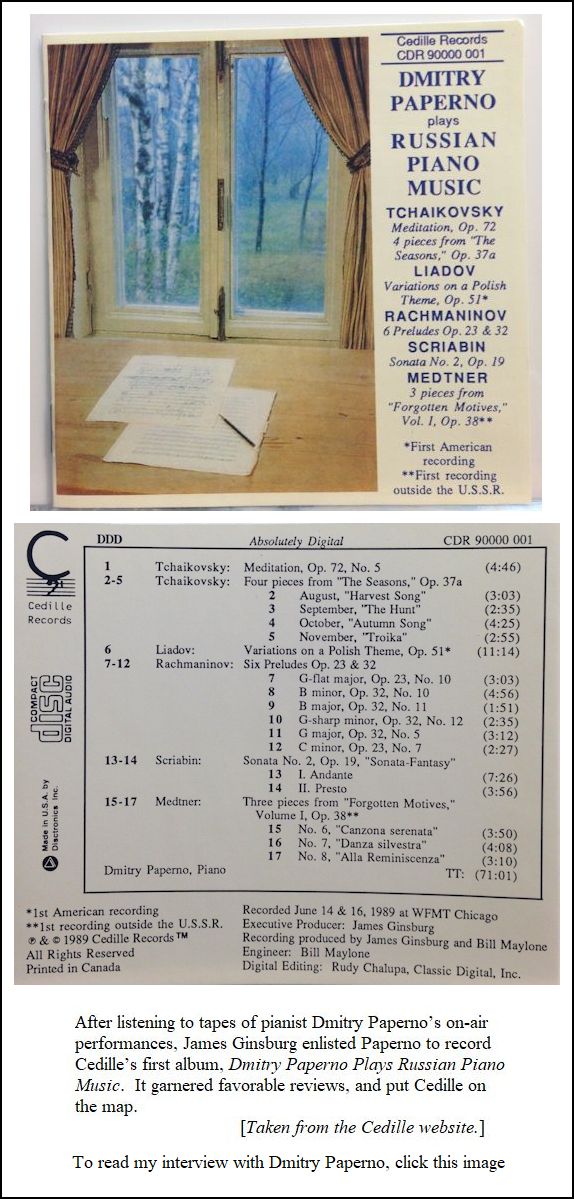

James Ginsburg (September 8, 1965 - ) was raised in New York City's Upper East Side, where he began collecting classical music recordings at an early age. While attending the University of Chicago, he managed classical programming at the university’s mixed-format radio station, WHPK. Before his undergraduate graduation, he began reviewing classical recordings for American Record Guide magazine. In 1989, Ginsburg launched a record label, Cedille Records, to record classical music produced by artists and composers in Chicago. The label is based in the Edgewater neighborhood of the city. Encouraged by the critical and commercial response to his early recordings, Ginsburg abandoned law school in his second year to devote himself full-time to Cedille. In 1994, Cedille became a not-for-profit under the umbrella of an operating foundation, now called Cedille Chicago, NFP (formerly The Chicago Classical Recording Foundation). This change gave Cedille the ability to produce more recordings and pursue more ambitious projects. Cedille Records releases an average of eight recordings per year. In 2009, the Chicago Tribune nominated Ginsburg as "Chicagoan of the Year," writing, "Let's hear it for James Ginsburg. The Chicagoan is one of the last independent entrepreneurs in classical recording, a man who has stuck to his artistic vision and made a success of it at a time of market shrinkage and industry downsizing." In 2010, Ginsburg won the Helen Coburn Meier and Tim Meier Charitable Foundation for the Arts Achievement Award. In making the award, the Foundation wrote, "We applaud Jim for seeing that Chicago has an abundance of stellar musicians. With his recording projects, Jim believes he can advance musicians' careers and serve the listening public in equal measure." Additional recognition and awards include being named a Jewish Chicagoan of the Year by the Chicago Jewish News in 2011. In 2012, he received the Ruth D. and Ken M. Davee Excellence in the Arts Award from the Illinois Philharmonic Orchestra. In 2016, Musical America named him one of The Top 30 Performing Arts Professionals of the Year, and in 2017, he was the honoree at the annual galas of both Chicago Opera Theater and the Rembrandt Chamber Musicians. Most recently, he received a 2020 Distinguished Service to the Arts Award from Lawyers for the Creative Arts. In 2019, Ginsburg was nominated for a “Producer of the Year, Classical” Grammy Award. In addition to this nomination, Cedille Records albums have won a number of Grammys, including the 2008, 2012, 2013, 2016 Awards for "Best Small Ensemble/Chamber Music Performance" for the contemporary music sextet Eighth Blackbird. In 2017, Third Coast Percussion also won for “Best Small Ensemble/Chamber Music Performance" for its Cedille album of music by composer Steve Reich. As Slate notes about Cedille, "Today it’s one of the most-respected

labels in the space, with six Grammy-winning records and 18 Grammy nominations." == Names which are links in this box and below

refer to my interviews elsewhere on my website. BD

|

© 1999 Bruce Duffie

This conversation was recorded in Chicago on October 27, 1999. Portions were broadcast on WNIB a couple of weeks later. This transcription was made in 2023, and posted on this website at that time. My thanks to British soprano Una Barry for her help in preparing this website presentation.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website, click here. To read my thoughts on editing these interviews for print, as well as a few other interesting observations, click here.

Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM, as well as on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio.

You are invited to visit his website for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.