RS: We’ll find

out! [Both laugh]

RS: We’ll find

out! [Both laugh] RS: I think I will

be. The

closest thing I’ve had to a disaster was in Santa Fe this past summer

when the lights went out on the stage and in the house. We were

really in the dark! Everybody kept going, and

it took about seven or eight seconds for the emergency lighting to kick

in. Of course that feels like an eternity in the middle of a

performance. But nobody stopped!

RS: I think I will

be. The

closest thing I’ve had to a disaster was in Santa Fe this past summer

when the lights went out on the stage and in the house. We were

really in the dark! Everybody kept going, and

it took about seven or eight seconds for the emergency lighting to kick

in. Of course that feels like an eternity in the middle of a

performance. But nobody stopped! RS: I hope we

do. I mean to. One

of the things that any conductor benefits from doing opera, in terms of

symphonic work, is to take that sense of dramatic timing and sense of

theater to the music making that is symphonic. What any

conductor should take from the symphonic world to the opera pit is a

kind of structural sense. That

always ends up being one’s primary task, in a way, when conducting a

symphonic work, to make sure the largest shape is presented and

understood.

RS: I hope we

do. I mean to. One

of the things that any conductor benefits from doing opera, in terms of

symphonic work, is to take that sense of dramatic timing and sense of

theater to the music making that is symphonic. What any

conductor should take from the symphonic world to the opera pit is a

kind of structural sense. That

always ends up being one’s primary task, in a way, when conducting a

symphonic work, to make sure the largest shape is presented and

understood. BD: But I assume

you would jump at the

chance to do either a new work or a premiere?

BD: But I assume

you would jump at the

chance to do either a new work or a premiere? BD: That’s just

fundamentals.

BD: That’s just

fundamentals. RS: I don’t pretend

to say that those things are

good for everybody, but those are the things that I regard as

good. And of course that’s according to my particular criterion,

my aesthetic inclinations, the things I value. I value craft; I

value precision; I value detail and subtlety; I value

beauty in a more abstract sense; sensuousness of sound.

RS: I don’t pretend

to say that those things are

good for everybody, but those are the things that I regard as

good. And of course that’s according to my particular criterion,

my aesthetic inclinations, the things I value. I value craft; I

value precision; I value detail and subtlety; I value

beauty in a more abstract sense; sensuousness of sound.|

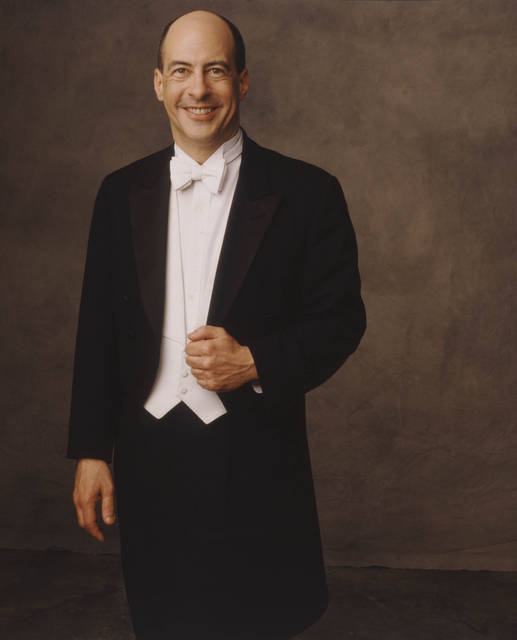

Robert Spano is among the most innovative and imaginative conductors of his generation. Now in his eighth season as Music Director of the Atlanta Symphony Orchestra, he has enriched its repertoire and elevated it to greater prominence. He has conducted the major orchestras of North America, including those in Boston, Chicago, Cleveland, Los Angeles, New York, Philadelphia and San Francisco. Among the orchestras he has led internationally are the Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra, Orchestra Filarmonica della Scala, Czech Philharmonic, Berlin Radio Sinfonie Orchestra, BBC Scottish and BBC Symphony Orchestras, City of Birmingham Symphony Orchestra, New Japan Philharmonic and Oslo Philharmonic. Mr. Spano has appeared with the opera companies of Chicago, Houston, and Santa Fe, and at the Royal Opera at Covent Garden and Welsh National Opera. In August 2009, Mr. Spano returns to the Seattle Opera to conduct three cycles of Wagner's monumental Der Ring des Nibelungen. In December, he conducts Golijov's Ainadamar with Dawn Upshaw and the Orchestra of St. Luke's in Carnegie Hall and appears with Carnegie's Zankel Band as part of its Bernstein Festival in a program of Bernstein gems. Other North American engagements will be with the New World Symphony and the Los Angeles Philharmonic. He is a guest soloist in Green Bay Symphony, playing Mozart's Piano Concerto No. 20 in D minor, K.466. This season's Atlanta programs reflect Mr. Spano's broad and diverse repertoire as well as his commitment to living composers, including commissions from Jennifer Higdon and Christopher Theofanidis, composers closely associated with Mr. Spano and the Atlanta Symphony Orchestra. Highlights in Atlanta are opening concerts celebrating Bach, Beethoven and Brahms, an "American Originals" festival, concert performances of John Adams's Dr. Atomic and Joseph Haydn's "The Creation", with set designer Anne Patterson. The Atlanta Symphony Orchestra's long and distinguished recording legacy with Telarc continues to flourish with Mr. Spano. Their discography includes music of David Del Tredici, Christopher Theofanidis, Jennifer Higdon and Michael Gandolfi, Sibelius' Kullervo, Brahms's Requiem, a recently released live recording of La Bohème and the Grammy award-winning recordings of Vaughan Williams's A Sea Symphony and Berlioz's Requiem. Mr. Spano and the ASO have also recently recorded two discs of the music of Osvaldo Golijov for Deutsche Grammophon: one including Three Songs and Oceana, and the other, the chamber opera Ainadamar, which was awarded two Grammys. Musical America's 2008 "Conductor of the Year," Mr. Spano was Music Director of the Ojai Festival in 2006, Director of the Festival of Contemporary Music at the Boston Symphony Orchestra's Tanglewood Music Center in 2003 and 2004, where he was Head of the Conducting Fellowship Program from 1998-2002, and was Music Director of the Brooklyn Philharmonic from 1996-2004. He is on the faculty of Oberlin Conservatory, and has received honorary doctorates from Bowling Green State University and the Curtis Institute of Music. Robert Spano makes his home in Atlanta. |

This interview was recorded in Chicago on October 26,

1998.

Portions (along with recordings)

were used on WNIB the following week. This transcription was

made and posted on this

website in 2009.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website, click here.

Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM, as well as on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio.

You are invited to visit his website for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.